Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

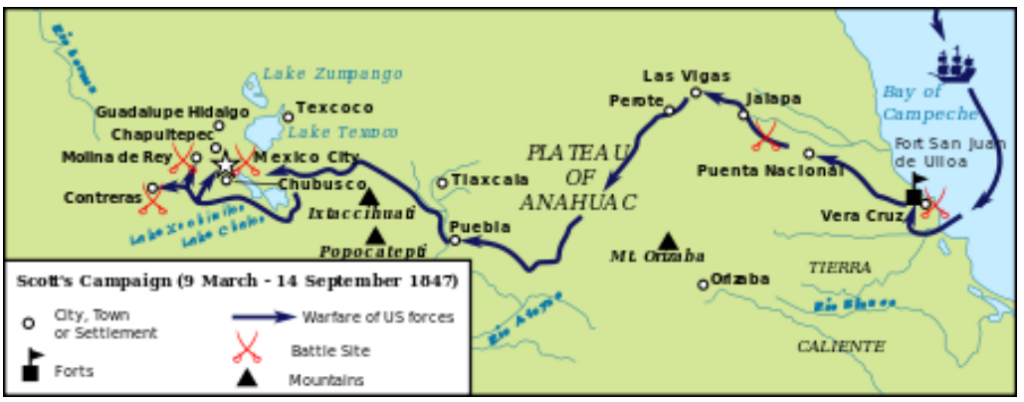

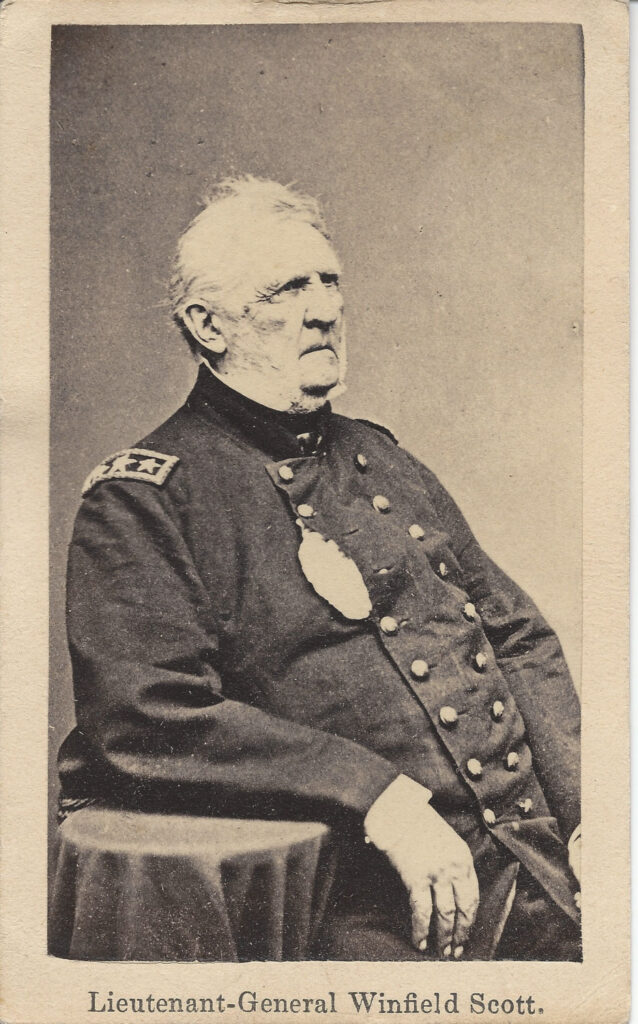

Chapter 128: General Scott Moves Inland In The South

March 9-29, 1847

Scott Takes Vera Cruz By Siege and Moves Inland

Two weeks after Taylor’s victory at Buena Vista, Scott executes America’s first major amphibious invasion, landing some 11,000 American troops on Sacrificios Island, just below the fortress city of Veracruz. The operation involves repeated trips ashore by 65 surf boats, each packed with 100 men and equipment, and lasts for over six hours. Once ashore, the men march north to surround the Mexican enclave, which includes 5,000 local civilians in addition to 4,400 garrisoned troops, under General Juan Morales.

The terrain leading into Veracruz is marked by the high chaparral and deep arroyos typical of Mexico’s landscape. In addition to these natural obstacles, cannon are arrayed along a 15-foot-high stone wall encircling the city and the road in is guarded by the formidable castle of San Juan D’Ulloa, and another 1,000 troops.

Scott immediately decides to siege the city. Colonel Joseph Totten oversees the plan, along with help from a 40-year old engineer, Captain Robert E. Lee. Lee’s placements of three 32 pound naval guns, hauled on land, will prove critical as the siege develops. Aside from Lee, several other soon to be famous West Pointers experience their first taste of battle at Veracruz, including Thomas Jonathan Jackson and George McClellan.

On March 22 Scott is ready to launch an all-out bombardment from land and sea, but, before beginning, he asks Morales to surrender. When the offer is refused, Scott begins his attack.

The results are devastating. For three days Veracruz suffers under constant barrages from field artillery and naval guns. Mortars lob solid iron balls weighing upwards of 30 lbs. into the city from the west. In the bay to the east, the U.S. fleet unleashes its Paixhans guns, with 68 lb. shells that whistle in at low trajectories and explode on contact. Some 6700 shot and shell weighing over 450,000 lbs. rain down on the defenders.

Naval officer Sydney Smith Lee, Robert’s older brother, observes the action from his frigate:

The battery’s fire was terrific. The shells were constant and regular discharges, so beautiful in their flight and so destructive in their fall. It was awful! My heart bled for the inhabitants.

brother, on the left

By March 25, the buildings and walls of Veracruz are crumbling and morale has worn thin. When Morale’s finally requests a truce to evacuate civilians, Scott refuses, insisting on a full surrender. After haggling, the final details are worked out on March 29.

Scott’s siege has lasted 20 days, and he has sustained a mere 58 casualties.

His gaze now shifts toward Mexico City, 225 miles inland.

Scott knows that this will not be an easy target. His army will be outnumbered along the way, and fall further distant from its supply base as it marches off. His enemy will have superior knowledge of the terrain ahead, and be motivated by fighting on and for its homeland. Still the General is confident of success.

He also knows from studying Napoleon that strict discipline in the ranks will be required to avoid alienating the local population and provoking partisan activity. His General Order 20 outlines harsh penalties for all Americans, soldiers or civilians, involved in robbery, rape, murder, destruction of property, and any acts affecting Catholic churches and worship.

April 17-18, 1847

The Battle At Cerro Gordo

After securing his hold over Veracruz, Scott sends a lead force of 8,500 men out of the city on April 8, heading northwest along the national road, with General David Twiggs and his 2nd Division in the lead.

Six days later they are on the winding road to Xalapa, where Santa Anna plans to ambush and kill them.

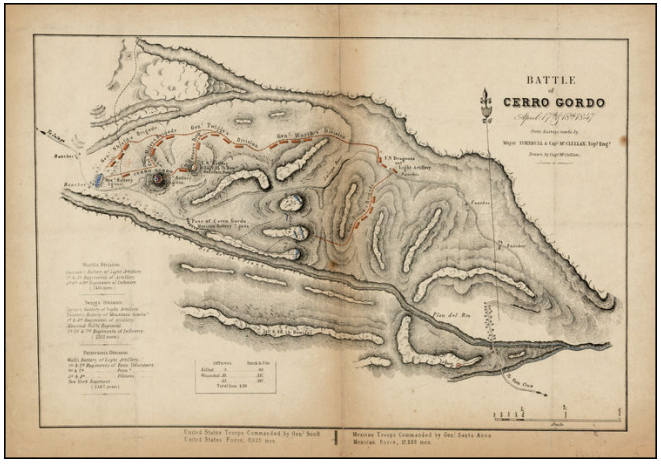

The Mexican General knows this ground particularly well, since it lies on his private estate. His plan is to lure the U.S. troops into a cul du sac formed by the Rio del Plana flowing along his right flank and the 950 foot high Cerro Gordo (“fat hill”) guarding his immediate left.

He arrays the bulk of his 12,000 troops in a classical L-shaped formation, with artillery batteries and infantry scattered across the Jalapa road and additional units ready to fire down from the Cerro Gordo on his left.

He also stations troops along a plateau to the east of the road, hoping to lure the Americans in or close off their subsequent line of retreat. With this shooting gallery in place, the Mexicans await the U.S. columns.

But Twiggs and his West Point engineers know an ambush when they see one, and they halt on April 14, north of the bend in the road leading down into Santa Anna’s position.

After scouting the area, they settle on a plan involving a trap of their own.

It hinges on enveloping the Mexicans, by hacking out a new road across the gullies and plateaus north of Santa Anna’s left flank, without being discovered. The work requires three full days to complete.

On April 17 Scott divides his army and advances. His light left wing, under Polk’s ex-law partner, General Gideon Pillow’s, demonstrates against the Mexican forces east of the road, while his main body, comprising Twiggs’ and Worth’s divisions, swoop down on Santa Anna from behind Cerro Gordo.

Battery placements by Lt. George B. McClellan prove especially galling to the Mexicans, and the Lieutenant is cited for valor during the assault.

By nightfall the surprised Mexicans are desperately trying to organize a credible defensive line.

As daybreak dawns on April 18, Colonel William Harney and his First Brigade dragoons deprive them of all hope — clawing their way to the top of Cerro Gordo and occupying the fortress there known as the Tower.

From this vantage point, American artillery now dominates the entire field below. Once the American flag appears atop the Tower, Santa Anna knows that his position is hopeless.

His troops along the eastern plateau surrender to Pillow’s command, and Santa Anna himself barely escapes with his life, on foot, amidst a panicked general retreat west toward Jalapa.

His losses are steep. Over 1100 Mexicans fall in the battle, and 3000 prisoners are taken, including five general officers. Another substantial depletion in artillery, smaller arms and ammunition also further weakens their capacity to fight on.

May – July, 1847

Scott Pauses To Balance Diplomacy And Warfare

Scott’s successes on the battlefield lead Polk and his cabinet to step up their plans for negotiating a treaty to end the conflict. The issues center on how much land they can convince the Mexicans to give up, and at what price. The cabinet agrees that an ideal outcome would involve all territory west, from where the upper Rio Grande touches New Mexico, to the Pacific – at a price not to exceed $30 million.

Secretary of War Marcy drafts an outline of the plan, to be delivered to Scott by Nicholas Twist, the number two official at the state department under Buchanan. Twist arrives at Veracruz on May 6 on the start of what will be a long and rocky mission.

By this time, Scott’s army has chased the Mexicans all the way from Cerro Gordo to Puebla, only 80 miles east of the capital.

This produces a mood within Mexico City itself that is a mixture of outrage and panic. After finally driving out the Spaniards to win independence, here comes another foreign invader – and a Protestant-dominated one at that – in search of conquest.

Calls go up in the capital to sack the government, declare martial law, draft all able-bodied men, and commence guerrilla warfare.

The last thing Scott wants to hear is talk of a religious war involving guerrilla bands operating outside the boundaries of conventional warfare.

On May 8, 1847, he issues a carefully worded proclamation to the people of Mexico. It asserts that the war is with government leaders, not with the people; that it’s about policy, not religion; and that, once ended, the Americans will exit Mexico, not occupy it.

With these reassurances comes a warning. Scott’s army is powerful and about to double in size, and it would be wise for the population to stay peacefully in their homes until the fighting is over.

Mexicans!–At the head of a powerful army, soon to be doubled-a part of which is advancing upon your capital…I think myself called upon to address you.

Americans are not your enemies, but the enemies, for a time, of those men who, a year ago, misgoverned you, and brought about this unnatural war between two great republics. We are the friends of the peaceful inhabitants of the country we occupy, and the friends of your holy religion, its hierarchy and its priesthood. The same church is found in all parts of our own country, crowded with devout Catholics, and respected by our government, laws and people…

Let all good Mexicans remain at home, or at their peaceful occupation…should Mexicans wisely accept this, war may soon be happily ended, to the honor and advantage of both belligerents. Then Americans, will be happy to take leave of Mexico and return to their own country.

Truth be told, Scott’s army in May is much less prepared to advance on the capital than he lets on.

The inevitable diseases that plague troops in the field have taken their toll, and the enlistment term for several volunteer regiments is about to expire. With his battle-ready forces under 6,000 men, he pauses in place at Puebla for eight weeks awaiting reinforcements.