Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 108: Fremont’s Second Expedition Explores The West Coast

May 29, 1843 – August 1844

A Second Fremont Journey Extends South Along The California Coast

No sooner has Fremont returned from his first journey than preparations begin for a second.

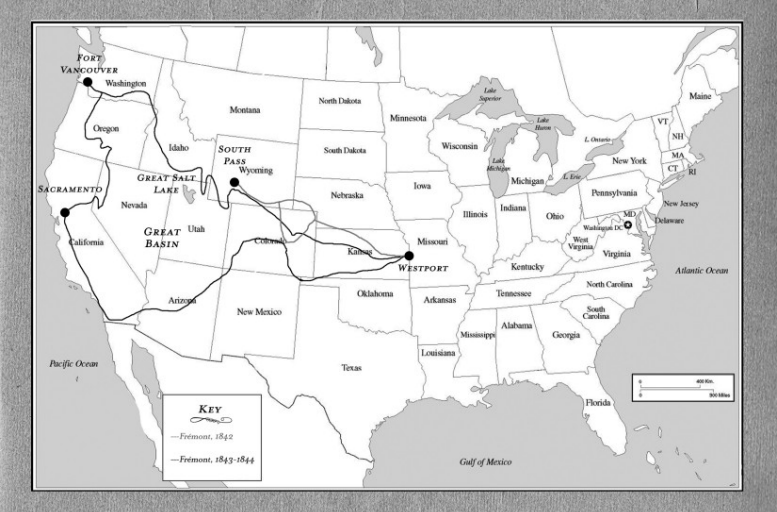

His assignment this time is to finish up mapping of the entire Oregon Trail route, pushing beyond the South Pass and heading northwest all the way to Fort Vancouver.

Fremont reassembles his roughly thirty-man crew, again including both Kit Carson and Charles Preuss, and sets out from St. Louis on May 29, 1843.

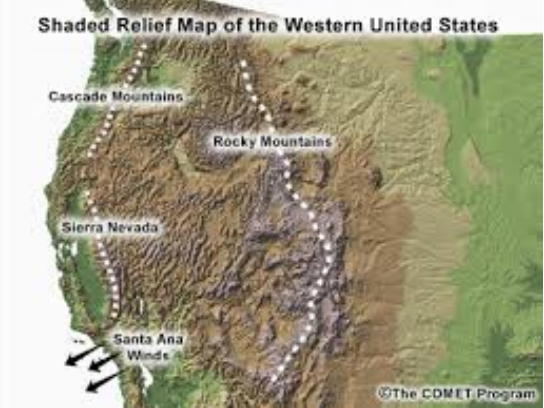

The outward trip is relatively uneventful, with the party reaching the Great Salt Lake on September 6 and Fort Vancouver in early November. At this point Fremont’s orders are to turn around and return home by the same route he has just completed. Instead he ignores tribal warnings about the winter ahead, and decides to swing south, heading along the eastern face of the Sierra Nevada range toward Sacramento, California. It is a decision that almost proves fatal.

By January 27, 1844, the expedition – some 27 men, 67 horses and mules, and a wheeled cannon — is strung out and stymied in the mountains. Charles Preuss captures the moment.

We are now completely snowed in. The snowstorm is on top of us. The wind obliterates all tracks which, with incredible effort, we make for our horses. The horses are about twenty miles behind and are expected to arrive tonight, or rather, they are now no longer expected. How could they get through? At the moment no one can tell what will really happen. It is certain we shall have to eat horse meat.

Indeed they do end up eating their horses, before being saved by Kit Carson who finally finds a pass across to the west slope of the Sierras and safety. The guide carves his initials into a tree marking the location, henceforth known as Carson’s Pass.

Another two week struggle finally ends on March 6, 1844, as they limp into Fort Sutter, east of Sacramento and soon to be famous for the nearby discovery of gold. A three-week rest there prepares them for the trip home, which takes them through the San Joachim Valley to the Old Spanish Trail through the Rocky’s in Utah.

Their fourteen month journey ends in August, when they arrive back in St. Louis.

Upon his return, Fremont is breveted to the rank of captain by the army, receives national publicity from the press, and is transformed into the “Great Pathfinder” by an adoring public. He is thirty-one years old, with a future ahead that will find him repeatedly in America’s spotlight over the next four decades.

1842-1844

Impact Of Fremont’s First Two Expeditions To The West

In reality, casting Fremont as the “Great Pathfinder” is more the product of publicity than performance – since almost all of the trails he takes have been “blazed” by many others before him.

Still his impact on America’s drive to “open the West” is profound.

For the first time, thanks to Fremont’s band, those eager to move across the continent have access to accurate maps to guide their way. These will prove invaluable in a few short years, first for the Army as west coast conflicts with Mexico and Britain materialize, and later when a flood of “forty-niners” head to the gold fields of California.

But beyond the sheer utility of the maps lies the magic of Fremont’s often poetic descriptions of the natural beauty he encounters from one camp to the next. How much of this prose springs from his pen versus that of his wife and co-author, Jesse, remains unknown. Its effect, however, on the imaginations of the American public is undeniable.

For the first time those living east of the Mississippi can sense the vastness of the Great Plains, the majesty of the Rocky Mountains, the fertile California vineyards, the mighty roar of buffalo herds, rushing rapids, the Pacific Ocean.

Any early stirrings about expansion that the politicians and public might have felt since the Louisiana Purchase are suddenly amplified by Fremont’s first two expeditions. In that sense, he becomes an important pathfinder of America’s commitment to manifest destiny.

Sidebar: Births And Deaths Of Frontiersmen

It is not surprising that Americans who abandoned hearth and home on their own precarious journey across the Atlantic would form a love affair with the frontiersmen who ventured overland to the Pacific.

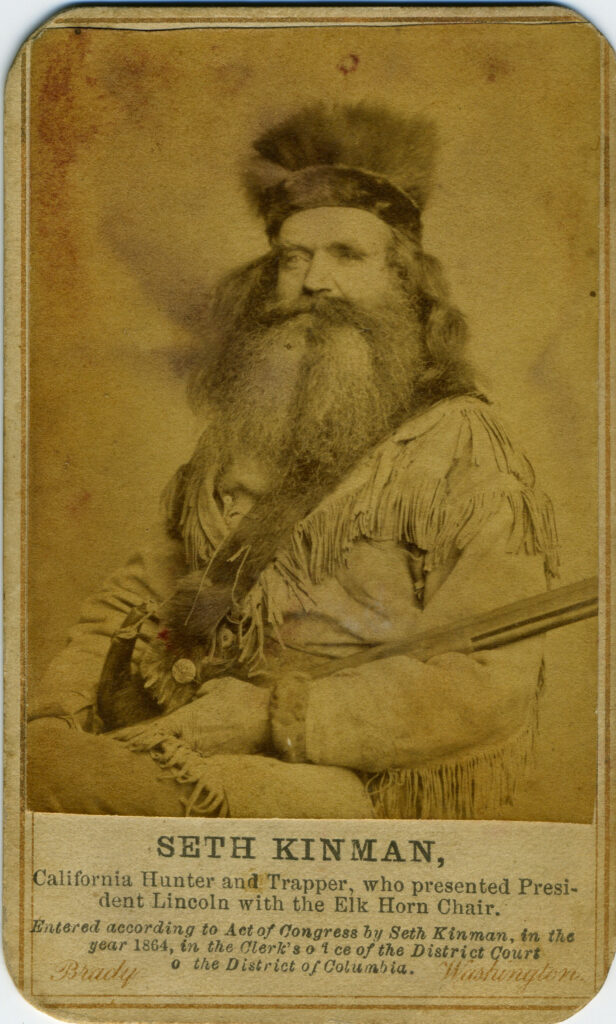

Daniel Boone heading through the Cumberland Gap into Kaintucky. John Jacob Astor chasing fur pelts across Canada to the west coast. George Clark and Meriwether Lewis blazing the Oregon Trail. Zeb Pike finding his 14,000 foot high peak in the southern Rockies. Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie losing their lives on behalf of the Republic of Texas. The Missouri trader, William Becknell, who first blazes the Santa Fe Trail. The mountain men, Jedediah Smith, William Ashley, Jim Bridger and William Sublette making their living in the Rockies, crossing the Mojave Desert, reaching into southern California. Ceran St. Vrain and William Bent with their trading post near Taos, New Mexico, and John Sutter, whose sawmill in Coloma, California, will spark the 1849 Gold Rush. John Fremont, Kit Carson and Charles Preuss, whose maps will prove invaluable to all who follow. The host of largely unknown native tribesmen who were there first and often guided the way.

These are America’s very own explorers, their names on towns and monuments, their deeds forever memorialized in literature and songs, their spirit embedded in the psyches of those about to realize the vision of “manifest destiny” in the latter half of the 19th century.

| Name | Birth | Death |

| Daniel Boone | Oct 22, 1734 | Sept 26, 1820 |

| George Rogers Clark | Nov 19, 1752 | Feb 13, 1818 |

| Robert Gray | May 10, 1755 | July 1806 |

| John Jacob Astor | July 17, 1763 | March 29, 1848 |

| Alexander Mackenzie | 1764 | March 12, 1820 |

| Touissant Charbonneau | 1767 | 1843 |

| William Ashley | 1770 | Mar 26, 1838 |

| Meriwether Lewis | Aug 18, 1774 | October 11, 1809 |

| John Colter | 1774 | Nov 22, 1813 |

| Zebulon Pike | Jan 5, 1779 | April 27, 1813 |

| Davy Crockett | 1786 | 1836 |

| William Becknell | 1788 | April 30, 1865 |

| Sacagewea | 1788 | 1812 |

| Stephen Austin | Nov 3, 1793 | Dec 27, 1836 |

| Benjamin Bonneville | April 14, 1796 | June 12, 1878 |

| James Bowie | 1796 | Mar 6, 1836 |

| Charles Wilkes | April 3, 1798 | Feb 8, 1877 |

| William Sublette | Sept 21, 1798 | July 23, 1845 |

| Joseph Walker | Dec 13, 1798 | Oct 27, 1876 |

| Jedediah Smith | Jan 16, 1799 | May 27, 1831 |

| Ceran St. Vrain | May 5, 1802 | Oct 28, 1870 |

| John Sutter | Feb 20, 1803 | June 18, 1880 |

| Charles Preuss | 1803 | 1854 |

| Jim Bridger | March 17, 1804 | July 17, 1881 |

| Kit Carson | Dec 24, 1809 | May 23, 1868 |

| William Bent | May 23, 1809 | May 19, 1869 |

| John Grizzly Adams | 1812 | 1860 |

| John C. Fremont | Jan 21, 1813 | July 13, 1890 |

| Seth Kinman | Sept 29, 1815 | Feb 24, 1888 |

| Jim Baker | 1818 | 1898 |