Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 172: Franklin Pierce’s Term

November 2, 1852

Pierce Wins In A Landslide

As the 1852 race plays out, the Democrats readily coalesce around Pierce, while the Whigs remain divided and generally unenthusiastic about Scott.

All four of Pierce’s opponents at the raucous Baltimore convention – Cass, Buchanan, Douglas and Marcy – quickly endorse him. Southerners are reassured by his firm commitment to the 1850 Compromise and to enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act, while Northerners see him as one of their own. On the campaign trail, he is blessed by a handsome appearance and a remarkable memory for faces and names and for speeches, which he routinely memorizes and delivers with what appears to be off the cuff ease and sincerity.

Those in the Young America movement point to his youth (at forty eight) and vigor, vis a vis the aging (at sixty-six) Scott, symbol of “a generation passing away.”

The Whigs go after Pierce’s limited experience (“an obscure individual”), and his record in the Mexican War, including unfair insinuations about his lack of battlefield courage. The Northern press insists that he is a religious bigot, based on New Hampshire laws banning Catholics from public office. They paint him as a total pawn of the South, an empty vessel who will bow to their every demand.

While the Whigs vigorously attack Pierce, they are never able to accomplish real unity and fervor behind Scott. His military exploits are every bit as impressive as those of the two former Whigs Presidents Harrison and Taylor, but his reputation as “Old Fuss ‘n Feathers” seems to signal devotion to protocol rather than conjuring up personal heroism. Southern Whigs who felt betrayed by Taylor’s opposition to expanding slavery to the west, are even more suspicious of Scott’s stand on slavery. Many Northern Whigs are put off by the party platform’s ringing endorsement of the Fugitive Slave Act.

In the end, Scott suffers the kind of political rout that he never experienced in warfare.

He carries only four states – Tennessee, Kentucky, Vermont and Massachusetts – worth 42 electoral votes against 254 for Pierce. Newspapers characterize the result as “a Waterloo defeat” and, indeed, it signals the death knell for the entire Whig Party.

Results Of The 1852 Presidential Race

| 1852 | Party | Pop Vote | Elect Tot | South | Border | North | West |

| Pierce | Democrat | 1,607,510 | 254 | 76 | 20 | 92 | 66 |

| Scott | Whig | 1,386,942 | 42 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 0 |

| Hale | Free Soil | 155,210 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Webster | Union | 6,994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Troup | So Rights | 2,331 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3,161,830 | 296 | 88 | 32 | 110 | 66 |

The turn-around from Taylor’s victory in 1848 is particularly evident in the North, where five states swing from the Whig to the Democrat column. The entire South and West, with the exception of Tennessee, are swept by Pierce and the Democrats.

Party Power By State

| States | Votes | 1848 | 1852 | Pick-Ups |

| Virginia | 15 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| North Carolina | 10 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| South Carolina | 8 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Georgia | 10 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Alabama | 9 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Mississippi | 7 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Louisiana | 6 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Tennessee | 12 | Whig | Whig | |

| Arkansas | 4 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Texas | 4 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Florida | 3 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| South | 88 | |||

| Delaware | 3 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Maryland | 8 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Kentucky | 12 | Whig | Whig | |

| Missouri | 9 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Border | 32 | |||

| New Hampshire | 5 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Vermont | 5 | Whig | Whig | |

| Massachusetts | 13 | Whig | Whig | |

| Rhode Island | 4 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Connecticut | 6 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| New York | 35 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| New Jersey | 7 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | Whig | Democrat | Democrat |

| Maine | 8 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| North | 110 | |||

| Ohio | 23 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Indiana | 13 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Illinois | 11 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Iowa | 4 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Michigan | 6 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| Wisconsin | 5 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| California | 4 | Democrat | Democrat | |

| West | 66 | |||

| Total | 296 |

The crushing defeat also carries over to Congress. In the House, the Democrats pick up 28 seats and restore the kind of decisive margin they held back in 1844.

Election Trends In The U.S. House

| Party | 1844 | 1846 | 1848 | 1850 | 1852 |

| Democrats | 142 | 112 | 113 | 130 | 158 |

| Whigs | 79 | 116 | 108 | 86 | 71 |

| American | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Free Soil | — | — | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| Constitutional Union | — | — | — | 10 | 0 |

| States’ Rights | — | — | — | 3 | 0 |

| Upcoming Congress | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 32nd |

| President | Tyler | Polk | Polk | Fillmore | Fillmore |

The Democrats also add three seats in the Senate, boosting their advantage from 35-24 to 38-22.

Election Trends In The U.S. Senate

| Party | 1844 | 1846 | 1848 | 1850 | 1852 |

| Democrats | 31 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 38 |

| Whigs | 25 | 21 | 25 | 24 | 22 |

| Free Soil | — | — | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Other | — | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 56 | 58 | 62 | 62 | 62 |

| Upcoming Congress | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 32nd |

| President | Tyler | Polk | Polk | Fillmore | Fillmore |

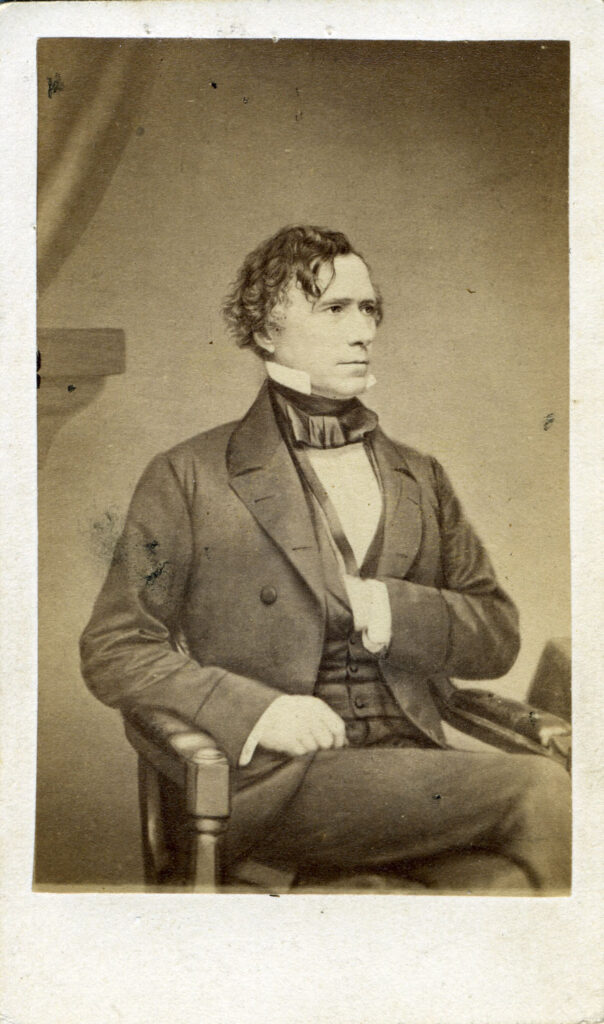

1804-1869

President Franklin Pierce: Personal Profile

Franklin Pierce grows up in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, the sixth of eight children in the family. His father, Benjamin, is a prominent figure in the state after volunteering for the Revolutionary War as a teenager, serving with bravery under General Washington, and later winning elections as Governor in 1827 and 1829, as a virulent anti-Federalist.

Two of Franklin’s older brothers fight in the War of 1812, and kindle his life-long wish for military fame. Though not academically inclined as a youth, his father pushes him into Exeter Academy and Bowdoin College, where he graduates in 1824. His reputation at school is that of a fun-loving, heavy drinking, fellow-well- met, with a unique photographic memory for what he reads and the people he meets – all characteristics that will make him a popular politician.

He studies law under sitting US Senator Levi Woodbury, who will later serve under Andrew Jackson as Secretary of the Navy and of the Treasury before being named a Supreme Court justice. Franklin passes the bar in 1827, launches a successful practice, and begins his pivotal role in making New Hampshire into the most reliable state in the entire nation for supporting the Democrat Party.

His political career blossoms immediately. He meets Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren in 1832, enters the US House in 1833 and moves on to the Senate in 1837. Along the way he marries his wife, Jane Appleton, his polar opposite – a minister’s daughter with Federalist leanings, considered plain, frail, intensely shy, and a teetotaler, who cajoles him into a temperance pledge, one he often breaks.

His positions in Congress mirror those of his party, opposing federal spending on infrastructure, the US Bank, soft money and any attempt to tamper with slavery. He is intensely critical of the abolitionists, favors the “gag rule” and is an early supporter of annexing Texas. These positions set him apart from his former friend and Dartmouth classmate, John Hale, and the two become arch-rivals at home.

Pierce resigns his Senate seat in 1842 after the Whigs come to power and retreats to New Hampshire, focusing on his family and his law practice. This hiatus is interrupted by the April 1846 declaration of war with Mexico and his chance to follow in the military footsteps of his father and brothers. What follows, however, is one frustration after another. He is chosen to command the 9th Infantry Regiment but it is very slow to form, and does not land at Vera Cruz until June 27, 1847, over one year into the conflict. Once there, Pierce leads his 2500 men and supply train inland on a 21 day, 100 mile trek to link up with General Scott. Along the way he fights off six hostile attacks, his finest showing in combat. On August 19 his horse falls on him, leaving him unconscious and with a severely damaged knee that keeps him out of the battle of Contreras. He also misses the final offensive on Mexico City owing to a bout of acute diarrhea.

Instead of the glory sought since childhood, his political opponents will twist his record into one of cowardice, a claim disputed many years later by U.S. Grant:

Whatever General Pierce’s qualifications may have been for the Presidency, he was a gentleman and a man of courage. I was not a supporter of him politically, but I knew him more intimately than I did any other of the volunteer generals.

While in Mexico, Pierce befriends many of his eventual Southern supporters, including Jefferson Davis, John Quitman, PGT Beauregard and Gideon Pillow

In December 1847 he resigns from the army and returns home in time for the sectional furor emanating from the Wilmot Proviso’s proposed ban on slavery in all Mexican lands acquired from the war. His positions follow the Democrat Party line, favoring the 1850 Compromise and the updated Fugitive Slave Law, both tilted in favor of the South.

As the nominating convention of 1852 approaches, Pierce has been out of public office for more than a decade. But his political power base in New Hampshire remains strong and eager to offer him up as a favorite son candidate. Instead he publicly backs his old legal mentor, Levi Woodbury, and insists that his name not be put forward unless the race appears hopelessly stalemated. That is exactly what happens. James Buchanan, Lewis Cass and William Marcy are deadlocked for over 40 ballots until Pierce’s name suddenly appears and he win on the 49th roll call.

On January 6, 1853 – nine weeks after the “Whig Waterloo,” his easy 51-44% election victory over his old commander, Scott – Pierce and his wife are on a train out of Boston which derails, killing their only remaining child, 11 year old Benny. Both parents suffer severe bouts of depression, with Jane viewing the tragedy as “God’s punishment” for her husband’s pursuit of high office. In turn she decides remain at home in New Hampshire for the first two years of his presidency.

1851

Pierce Selects A Strong Cabinet

As Pierce considers his cabinet options he is acutely aware of the fact that he was nobody’s first choice of those at the Baltimore convention. He also recognizes that while the Whigs may have collapsed for good with Scott’s defeat, the potential for rifts within his own Democrats need to be addressed.

In the North, some residual animus remains in New York between the so-called “Hunkers” and the “Barnburners,” although the two Van Burens and John Dix have abandoned their temporary flight to the Free Soil Party.

But the overriding fault line lies between Democrats in the North vs. the South, even after the 1850 Compromise Bill. Northerners are upset over the presence of slave catchers in their towns. Southerners feel that their constitutional rights to “property in slaves” has still not been affirmed by Congress, and that” “popular sovereignty” is then affirmed by Congress, and that hardly the guarantee they desire.

The overriding fear then among Southerners is that slavery will be banned in the new Mexican Cession lands. John Calhoun and the Fire-Eaters have been warning of this all along, and now the prospect is sinking in more broadly, especially across the lower South. Pierce’s challenge will be to try to hold the moderate Democrats together and prevent an open revolt among the Southern outliers.

Differing Factions Within The Democratic Party In 1852

| Southern Outliers | Positions | People |

| Fire-Eaters | Oppose 1850 Compromise & threaten secession | Rhett, Hammond, Yancey |

| Unionists | Reservations about 1850, but not favoring secession | Cobb, Hunter |

| Moderates Across Sections | Pro-Compromise and party solidarity | Pierce, Buchanan, Cass, Douglas, Marcy, Davis, Benton, Houston, Johnson, Breckinridge, Guthrie, Dickinson, the Van Burens |

Within this context, Pierce sees his first task as trying to choose a cabinet acceptable to all sides.

For Secretary of State he settles on William Marcy, the sixty-six year old New Yorker who served as Senator and Governor of his state, joined Polk’s cabinet as Secretary of War and then sought the presidential nomination in Baltimore, backing the 1850 Bill and party unification.

Next comes Jefferson Davis who has opposed the Compromise, but whose military career makes him an obvious choice for the War Department. He will also link Pierce into various States’ Rights factions, tempered by his firm commitment to the Union.

His pick for Attorney General is his Mexican War acquaintance, Caleb Cushing, a renowned Northern Doughface, whose history includes family wealth, Harvard, many years as a Whig before being drummed out for supporting John Tyler. He has also been a Minister to China, and a foursquare supporter of the 1850 Bill.

Treasury goes to the Kentucky businessman, “hard money” banker, college president and developer of the city of Louisville, James Guthrie. He is sixty years old and frequently touted as a White House contender. After his four years in the job, many will call him the best Treasury leader since Hamilton.

After promoting Marcy for State and landing the job he wants as Ambassador to the UK, James Buchanan weighs in again with Pierce on behalf of naming a Roman Catholic, Pennsylvania Judge James Campbell as Postmaster General. This is a controversial pick aimed at locking in future votes from the growing European immigrant groups.

James Dobbins, the North Carolinian House member whose last minute praise in Baltimore led to Pierce’s victory, earns his reward as Secretary of the Navy – while long-term friend of Lewis Cass and twice Governor of Michigan, Robert McClelland, gets the Interior posting.

Franklin Pierce’s Cabinet

| Position | Name | Home State |

| Secretary of State | William Marcy | New York |

| Secretary of Treasury | James Guthrie | Kentucky |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | Mississippi |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | Massachusetts |

| Secretary of Navy | James Dobbin | North Carolina |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | Pennsylvania |

| Secretary of Interior | Robert McClelland | Michigan |

In the end, Pierce’s patchwork quilt cabinet will serve him well. All seven men complete their entire terms with effort and integrity; they come to respect their President; and two who hardly know him in 1852, Marcy and Davis, become his lifelong friends.

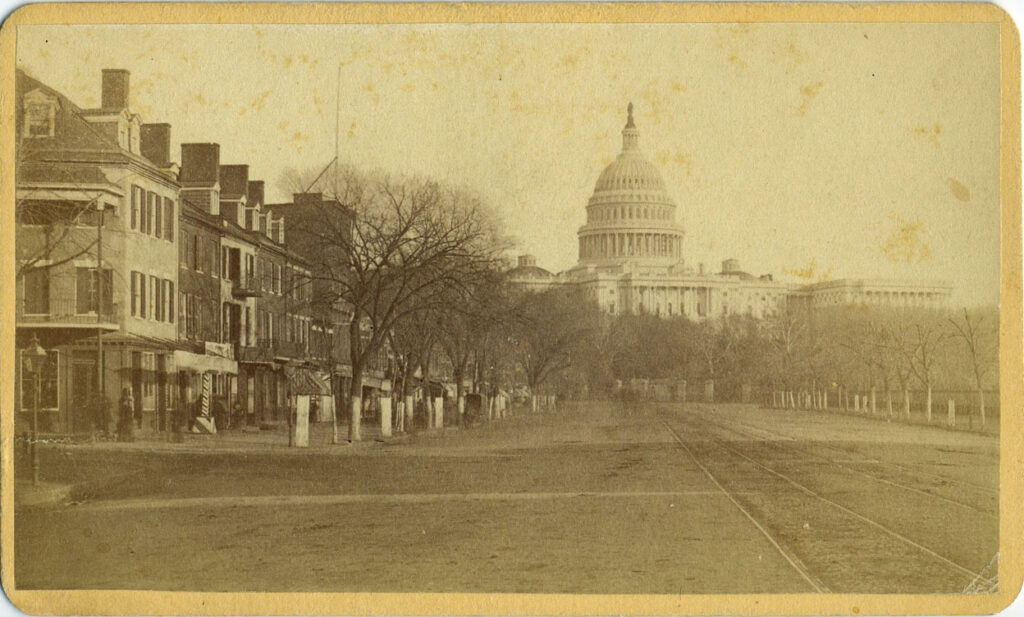

March 4, 1853

Inaugural Address

Pierce’s Inaugural ceremonies play out on a chilly overcast day in Washington marked by intermittent snow. After an open carriage ride up Pennsylvania Avenue to the capitol, he steps onto the east portico to deliver his remarks. The speech runs to some 3300 words, and, true to form, he delivers it all from memory.

Only two months have passed since the tragic loss of his only remaining child, and his opening lines are both touching and revealing under the circumstances:

My Countrymen: It a relief to feel that no heart but my own can know the personal regret and bitter sorrow over which I have been borne to a position so suitable for others rather than desirable for myself… You have summoned me in my weakness; you must sustain me by your strength.

Like many a predecessor, he begins by reflecting on the wisdom and accomplishments of the founders.

The thoughts of the men of that day were as practical as their sentiments were patriotic. They wasted no portion of their energies upon idle and delusive speculations, but with a firm and fearless step advanced beyond the governmental landmarks which had hitherto circumscribed the limits of human freedom… The oppressed throughout the world from that day to the present have turned their eyes hitherward, not to find those lights extinguished or to fear lest they should wane, but to be constantly cheered by their steady and increasing radiance.

His ties to the “Young America” movement and his belief in Manifest Destiny are captured in a full-throated endorsement of further geographical expansion.

The stars upon your banner have become nearly threefold their original number; your densely populated possessions skirt the shores of the two great oceans… The policy of my Administration will not be controlled by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion. Indeed, it is not to be disguised that our attitude as a nation and our position on the globe render the acquisition of certain possessions not within our jurisdiction eminently important for our protection, (and) for the preservation of the rights of commerce and the peace of the world.

At the same time, he decries aggression and pledges to “cultivate kindly and fraternal relations with the rest of mankind” in his foreign policies — while also reaffirming a commitment to the Monroe Doctrine.

The rights, security, and repose of this Confederacy reject the idea of interference or colonization on this side of the ocean by any foreign power beyond present jurisdiction as utterly inadmissible.

He references his time in the military, concluding that while a large standing army is unnecessary; his goal will be to strengthen the nation’s military science and officer corps.

The opportunities of observation furnished by my brief experience as a soldier confirmed in my own mind the opinion, entertained and acted upon by others from the formation of the Government, that the maintenance of large standing armies in our country would be not only dangerous, but unnecessary…. They also illustrated the importance–I might well say the absolute necessity–of the military science and practical skill furnished…by the institution which has made your Army what it is under the discipline and instruction of officers.. distinguished for their solid attainments, gallantry, and devotion to the public service…unobtrusive bearing and high moral tone.

The administration of domestic affairs will be carried out with integrity and economy.

In the administration of domestic affairs you expect a devoted integrity in the public service and an observance of rigid economy in all departments, so marked as never justly to be questioned.

As he begins to wind down his remarks he turns to the threats he sees to the Union. As a pure Jeffersonian Democrat, one of these lies in concentrating too much power in the central government. This, he says, is inconsistent with the intent of the Constitution, and he promises to curb federal intrusion and respect the rights of the states – all music to the ears of his southern supporters.

But these are not the only points to which you look for vigilant watchfulness. The dangers of a concentration of all power in the general government of a confederacy so vast as ours are too obvious to be disregarded. You have a right, therefore, to expect your agents in every department to regard strictly the limits imposed upon them by the Constitution of the United States. The great scheme of our constitutional liberty rests upon a proper distribution of power between the State and Federal authorities, and experience has shown that the harmony and happiness of our people must depend upon a just discrimination between the separate rights and responsibilities of the States and your common rights and obligations under the General Government…If the Federal Government will confine itself to the exercise of powers clearly granted by the Constitution, it can hardly happen that its action upon any question should endanger the institutions of the States or interfere with their right to manage matters strictly domestic according to the will of their own people

Finally Pierce faces squarely into the issue of “involuntary servitude,” while insisting that his views have been clear all along.

My own position upon this subject was clear and unequivocal, upon the record of my words and my acts, and it is only recurred to at this time because silence might perhaps be misconstrued…

He calls upon all sides to debate the issue in a “calmly,” avoiding “sectionalism and uncharitableness,” and on behalf of the “perpetuation of the Union.”

The field of calm and free discussion in our country is open, and will always be so, but never has been and never can be traversed for good in a spirit of sectionalism and uncharitableness…In expressing briefly my views upon an important subject rich has recently agitated the nation to almost a fearful degree, I am moved by no other impulse than a most earnest desire for the perpetuation of that Union which has made us what we are…

Having said that he asserts that the Constitution recognizes “involuntary servitude;” that the “rights of the South” in this regard demand respect; that the “compromise measures” of 1850” must be “unhesitatingly carried out;” and that, in so doing, all “fanatical excitement” over the issue should be laid “at rest.”

I believe that involuntary servitude, as it exists in different States of this Confederacy, is recognized by the Constitution. I believe that it stands like any other admitted right, and that the States where it exists are entitled to efficient remedies to enforce the constitutional provisions. I hold that the laws of 1850, commonly called the “compromise measures,” are strictly constitutional and to be unhesitatingly carried into effect.

I believe that the constituted authorities of this Republic are bound to regard the rights of the South in this respect as they would view any other legal and constitutional right, and that the laws to enforce them should be respected and obeyed, not with a reluctance encouraged by abstract opinions as to their propriety in a different state of society, but cheerfully and according to the decisions of the tribunal to which their exposition belongs.

Such have been, and are, my convictions, and upon them I shall act. I fervently hope that the question is at rest, and that no sectional or ambitious or fanatical excitement may again threaten the durability of our institutions or obscure…our prosperity

Pierce closes traditionally, calling upon “God and His overruling providence” to keep the nation secure.

Standing, as I do, almost within view of the green slopes of Monticello, and, as it were, within reach of the tomb of Washington, with all the cherished memories of the past gathering around me like so many eloquent voices of exhortation from heaven, I can express no better hope for my country than that the kind Providence which smiled upon our fathers may enable their children to preserve the blessings they have inherited.

March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

Overview Of Franklin Pierce’s Term

From the moment he sets foot in the White House, Franklin Pierce is focused on holding his beloved Democratic Party together as the necessary path to preserving the Union.

For years the Whig Party has been the political foil against which the Democrats could rally. Early battles centered on Tariff rates; then came controversies over a National Bank and spending behind federal infrastructure projects; more recently the disputes over expansion, the Texas Annexation and the Mexican War. At every turn, Democrats who might have internal differences with each other were always able to see a much greater evil in the form of Henry Clay and his American System platforms.

By 1852, however, these differences have become less intense. Public attention has turned to newer issues, how best to paste together the new western Territories with the old eastern States; the sudden influx of immigrants, especially Catholics from Ireland and Germany, and their impact on the status quo privileges of the dominant Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture; and, of course, finality around the future course of slavery and of white-black social relations.

As a proponent of the Young America Movement, Pierce tends to rely on Stephen A. Douglas to take the lead in Congress on these emerging issues.

On economic policy, Douglas is almost Whig-like in his support of infrastructure projects aimed at upgrading railroads, roads, waterways and communication systems throughout the west. While Pierce is forever uncomfortable with the constitutionally of spending federal dollars this way, he tends to go along on projects that support commerce and bonding between the west and the east.

One such project will involve Congressional debate over the routing of a transcontinental railroad which will eventually extend over 1,912 miles and open in 1869. Four different routes will be proposed, with cities and property owners along the chosen path certain to enjoy financial windfalls.

To gain Southern support for a “central route” through Chicago that he favors (and is personally invested in), Douglas introduces his Kansas-Nebraska Act in January 1854. This Bill is generally regarded as the spark that leads inevitably to the Civil War. It does so by reneging on the 36’30” boundary line in the Missouri Compromise which divided Free States from Slave States within the Louisiana Purchase territories. Once passed, it becomes a rallying point for politicians and citizens alike who oppose the presence of slaves – and even free blacks – in the west.

Among these opponents are the remnants of several parties in search of a new raison d’etre, including: the dispirited Whigs, the abolitionist and white supremacist wings of the Free Soil movement, and a new anti-immigrant group soon to be labeled the Know Nothings. By the conclusion of Pierce’s term, this mixed bag will begin to coalesce under the banner of Republicans.

To further console and solidify his Southern Democrats, Pierce embraces more territorial expansion, first in the Gadsden Purchase of land along the Mexican border required for a railway route across the 32nd parallel, and later in official pursuit of acquiring Cuba and in his lax response to filibustering actions by William Walker in Nicaragua.

But midway through his term comes the crisis that will convert the angry rhetoric over slavery into the violence that will eventually topple the Union.

It is focused in the new Kansas Territory and involves a battle between forces anchored in Missouri who intend to make it a Slave State and new settlers from the North equally intent on a Free State outcome.

When the Democrat’s theoretical solution – “let the voters decide” – breaks down in the face of fraudulent elections, the two sides engage in a series of vicious confrontations lasting over the next five years and forever marking the territory as “Bloody Kansas.”

The violence in Lawrence and along the Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas is soon replayed in the U.S. Senate when the outspoken abolitionist, Senator William Sumner of Massachusetts is nearly caned to death on the floor by the South Carolina man, Preston Brooks.

Franklin Pierce will run through three Territorial Governors in his attempt to solve the Kansas crisis, before handing the conflict over to his successor, Buchanan, who will only make matters worse.

The national economy continues to thrive during Pierce’s term as industry rushes west toward the gold fields of California and railroad construction booms. By 1856, however, concerns over speculation in both new land and new trains sharply dampens the growth.

Key Economic Overview

| 1852 | 1853 | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 | |

| Total GDP ($000) | $3,066 | 3,311 | 3,713 | 3,975 | 4,047 |

| % Change | +12% | +8 | +12 | +7 | +2 |

| Per Capita GDP | $123 | 128 | 138 | 143 | 142 |

Pierce lives for over eleven years after leaving office. He tours Europe and vacations in the Bahamas, but always returns to his home in Concord, NH. In the 1860 race he backs Cushing and then Breckinridge as his Democratic Party divides. During the war his loyalty is questioned off and on, especially given his closeness to Jefferson Davis. His health deteriorates after the loss of his wife in 1863 and his friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, in 1864. Always a heavy drinker, he finally dies of cirrhosis of the liver in 1869.

Key Events: Pierce’s Term

| 1852 | |

| November 2 | Pierce wins presidency in a landslide |

| December | The American (Nativist) Party gathers supporters |

| 1853 | |

| March 2 | Washington territory created out of northern Oregon territory |

| March 3 | Congress appropriates $150,000 to survey routes for a transcontinental railroad |

| March 4 | Franklin Pierce inaugurated |

| April 18 | Vice-President William King dies and not replaced; David Atchison now next in line. |

| May 19 | James Gadsden to negotiate with Mexico over land in southern NM & Arizona |

| May 31 | Second Arctic exploratory expedition sets out under command of Dr. Elisha King |

| June | Expeditions begin to explore four routes for the transcontinental railroad |

| July 8 | Commodore Perry arrives at Yedo Bay, Japan, and delivers Fillmore letter to the Emperor |

| December 30 Or 6/29 app | Gadsden Treaty adds 29,640 square miles in Southwest for $10 million to Mexico |

| Year | 1.2 million copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold during the year |

| 1854 | |

| January 4 | Hoping to route the transcontinental railroad through Chicago, Douglas proposes dividing Nebraska Territory in two (Kansas & Nebraska), assuming one will be Free and one Slave, even though both lie north of the 36’30” Missouri Compromise Free-only line |

| January 16 | Kentucky Senator Archibald Dixon proposes to formally repeal the Missouri Compromise |

| January 17 | Senator Charles Sumner proposes an amendment to reaffirm the Compromise |

| January 18 | Filibusterer William Walker declares himself President of Sonora (Mexican California) |

| January 24 | Several Democratic senators led by Chase and Sumner attack Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska bill as a plot by Southern slave-owners to violate the 36’30” line |

| March 20 | Meeting of anti-slavery men held at Ripon, WI to form a Republican Party |

| March 31 | Commodore Perry returns to Japan and induces Japan to sign Treaty of Kanagawa which opens ports to US trading ships |

| April 26 | The Emigrant Aid Society formed in Worcester, Mass. to encourage antislavery men to settle in Kansas as a Free State |

| May 8 | Filibusterer William Walker returns to U.S. after failed incursion into Mexico |

| May 26 | The Senate passes the Kansas-Nebraska Act with a clear majority & Pierce signs it into law. |

| Wendell Phillips and mob storm Boston court house in failed attempt to free another runaway slave, William Burns. | |

| May 31 | Pierce warns against filibustering in Cuba. |

| June 5 | US and Britain sign treaty on fishing rights off New Brunswick |

| July 6-13 | Anti-slavery Democrats, Whigs and Free Soilers meet in Michigan to demand repeal of both the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Fugitive Slave Act. Leaders include Sumner, Chase, Julian, Bates and Browning. |

| July 19 | Wisconsin Supreme Court declares Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional and frees Mr. Booth who had been arrested for helping a runaway slave |

| July | Federal land grant opened in Kansas to support settlers |

| October 7 | Pierce appoints Andrew Reeder as first Territorial Governor of Kansas |

| October 16 | Abraham Lincoln delivers speech in Peoria condemning the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He affirms the rights of Southern slave-owners while also supporting gradual emancipation. |

| October 18 | US Minister to Spain Pierre Soule negotiates the “Ostend (Belgium) Manifesto” with European ministers supporting the annexation of Cuba by force if necessary. |

| November 29 | Missouri ruffians cross Kansas border to support a pro-slavery representative to DC |

| November | The Know Nothing Party holds a convention in Cincinnati |

| December | Voting for 35th Congress is under way |

| Year | Henry David Thoreau publishes Walden |

| 1855 | |

| January 16 | Territorial legislature meets for the first time in Nebraska |

| February 24 | Final report published on transcontinental railroad route surveys |

| March 3 | Secretary of State Marcy rejects the “Ostend Manifesto” after negative public reactions. |

| March 4 | 35th Congress convenes |

| March 30 | Missouri ruffians again invade Kansas to elect a pro-slavery territorial legislature, which Governor Reeder accepts as legitimate |

| June 5 | Southerners dominate Know-Nothing Party convention in Philadelphia |

| July 2 | Kansas pro-slavery dominated legislature meets in Pawnee and expels anti-slavery men |

| July 31 | Pierce removes Kansas Governor Reeder for opposing the pro-slavery legislature |

| August 4 | Free State supporters meet at Lawrence, Kansas and call for their own legislature |

| September 3 | Filibusterer William Walker assumes actual control over Nicaragua during a civil war, with the backing of the Accessory Transit Company which seeks a canal across the land. |

| October 1 | Pro-slavery forces in Kansas elect J. W. Whitfield as delegate to DC congress |

| October 9 | Anti-slavery men in Kansas elect ex-Governor Reeder as their delegate to DC |

| October 13 | Filibusterer William Walker takes control over the nation of Nicaragua |

| November 12 | Free State Kansans hold convention in Topeka and adopt a constitution that outlaws slaves and then also all blacks from residing in the state |

| November 26 | War breaks out along the Wakarusa River between 1500 Border Ruffians and anti-slavery forces who also fortify the town of Lawrence |

| December 8 | Pierce issues a proclamation critical of Walker’s actions in Nicaragua |

| December 15 | Free State Kansans approve the Topeka Constitution banning slaves and all blacks |

| Year | Roughly 400,000 immigrants arrive in New York during the year |

| Frederick Douglass publishes his autobiography | |

| Feminist Lucy Stone marries Henry Blackwell with both promising gender equality | |

| 1856 | |

| January 15 | Free State Kansans elect their own Governor, Charles Robinson, which is called an act of rebellion by Pierce |

| January 24 | Georgia Senator Robert Toombs delivers pro-slavery speech at Tremont Temple in Boston |

| February 2 | Divisions in the House over the Kansas-Nebraska Act provoke a two-month stalemate in selection of a Speaker, with Know-Nothing Nathaniel Banks finally selected. |

| February 22 | The Know Nothing (American) Party holds a convention in Philadelphia and select Millard Fillmore as their presidential candidate, while also attacking the “Black Republicans” in their platform. |

| March 4 | Free State Kansans in Topeka apply for statehood with Republican support, but Douglas blocks the measure demanding that a new constitutional convention be held first. |

| April 21 | The first railroad bridge across the Mississippi is completed between Illinois and Iowa |

| May 21 | Pro-slavery Kansans attack the Free State stronghold at Lawrence and |

| May 22 | Three days after a speech critical of Andrew Butler of South Carolina, Senator Charles Sumner is caned at his desk and critically wounded by Butler’s nephew, Preston Brooks |

| May 24 | Abolitionist John Brown leads attack killing five pro-slavery settlers at Pottawattamie Creek |

| June 2-6 | The Democrats meet in Cincinnati and choose James Buchanan as their presidential nominee and John C. Breckinridge as VP on a platform that supports the 1850 Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. |

| June 15 | A break-away group of anti-slavery Know Nothings holds a convention in New York, choosing John C. Fremont for President behind a “Free Territory and Free Kansas” banner and a platform attacking immigrants and Roman Catholics and calling for “Americans only to govern America.” |

| June 17-19 | The first Republican Party convention meets in Philadelphia and also nominates Fremont for President; its platform calls for a Free Kansas and approval of a transcontinental railroad. |

| July 3 | The House votes to admit Kansas as a Free State, but the Senate rejects as the session ends |

| July 4 | Federal troops from Ft. Leavenworth arrive at Topeka & dispel the Free State legislature |

| September 9 | Pierce appoints John W. Geary as the new Governor of the Kansas Territory |

| September 15 | Geary sends Federal Troops to halt an impending attack by some 2500 Border Ruffians |

| September 17 | Remaining Whigs meet in Baltimore and back the Know Nothing ticket of Fremont and Andrew Donelson, the adopted son of Andrew Jackson |

| November 4 | James Buchanan elected 15th President |

| 1857 | |

| January 15 | Abolitionist Garrison speaks at the Massachusetts Disunion Convention apparently showing support for their slogan “no union with slaveholders.” |

| Jan – Feb | Pro-slavery Kansans meet in Lecompton to call for a census and the election of delegates to a constitutional convention. Governor Geary vetoes the proposal. |

| March 3 | Tariff Act of 1857 lowers rates to 20%. |

| March 4 | Kansas Governor Geary resigns after criticism from Pierce for resisting LeCompton |

| James Buchanan is inaugurated |

Once the results are in, the search begins again to create a new opposition party capable of challenging the Democrats at the national level.

During Pierce’s term the outline for such a party, known as the Republicans, will be visible in the convergence of four often wildly different political interests:

- Northern Whigs looking for a new home for their American System principles;

- Liberty Party members and others who oppose slavery on moral grounds and aim to end it;

- Certain Free Soilers who back Wilmot’s call for “whites-only” territory and land grants in the west; and

- A resurgent anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant party calling themselves the “Know Nothings.”