Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

Chapter 67: Four Parties Vie For The Presidency In 1832

January 1831

Jackson Announces His Run For A Second Term

Despite his promise to serve for one term only, Jackson changes his mind, and in January 1831 the Washington Globe – his official newspaper organ edited by Francis Preston Blair – announces that he will run again in 1832.

His opponents have already nicknamed him “King Andrew,” for what they regard as his autocratic approach to running the federal government. Their intent is to dislodge them in any way they can.

Three different men from three different political parties will lead the charge against Jackson. Two are very familiar figures on the national stage – Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.

The third – Thurlow Weed – will achieve fame in the decades ahead, not as a candidate for office, but as a political strategist intent on creating a new Anti-Democrat party capable of winning the White House.

1832

Henry Clay Becomes The First “Whig Party” Candidate

Jackson’s principal opponent in 1832 will be his mortal enemy, Henry Clay, who is back in Congress as of November 1831, as Senator from Kentucky.

Clay remains appalled by Jackson’s personal comportment, his lack of presidential gravitas, and his willingness to see the Executive run roughshod over the Legislature which, he believes, the founders regarded as the dominant branch of government.

Since Adams’ defeat in 1828, he has established his new “Whig Party” based on the principles laid out in his “American System.”

But Clay knows that “King Andrew’s mobocracy” will be hard to beat in 1832.

Jackson’s Democratic Party base centers around the common man struggling to make his way in America: small farmers, western settlers, city laborers and Irish Catholic immigrants. Its policies call for cheap land prices, opposition to all forms of privilege, and great fiscal restraint to avoid burdening the people with excessive federal spending and taxation.

Clay decides to fight it out with Jackson over management of the economy.

He argues that prosperity for all depends on a federal government that invests more money, not less, to support growth.

He says that Jackson is wrong in his laissez-faire reliance on individual states to make investments that help America as a whole. Instead, this duty belongs with the federal government.

To apply the aggregate industry of our nation…to produce the largest sum of national wealth.

Rather than relying on exports to maximize wealth, Clay wants to focus on developing a vibrant “home market” for goods,

The greatest want of civilized society is a market for the sale and exchange of the surplus of the produce of the labor of its members….The creation of a home market is not only necessary to procure for our agriculture a just reward of its labors, but it is indispensable to obtain a supply of our necessary wants.

Future economic success also hinges on recognition of the growing “power of machinery” to complement traditional manual labor.

Labor is the source of all wealth; but it is not natural labor only. And the fundamental error of the gentleman from Virginia…consists in their not sufficiently weighing the importance of the power of machinery. In former times, when but little comparative use was made of machinery, manual labor and the price of wages were circumstances of the greatest consideration. But it is far otherwise in these latter times.

Clay, like Hamilton before him, is in favor of nourishing the manufacturing sector, as a necessary path to national wealth.

The unprotected manufactures of a country are exposed to the danger of being crushed in their infancy, either by the design or from the necessities of foreign manufacturers.

Clay’s blueprint call for transforming the nation into an international economic powerhouse by:

- Investing in infrastructure (roads, highways, canals, schools)

- Supporting a national banking system to distribute capital

- Funding the government through sensible taxation policies

Unfortunately for Clay, his ideas come at a time when most Americans are pleased with economic results under Jackson.

1831-1832

Calhoun Dedicates His Future To Promoting Southern States Rights

Once Jackson names Martin Van Buren as his running mate for 1832 and designated heir apparent, John C. Calhoun sets a new political course for himself as the leading national defender of Southern states rights and the institution of slavery.

His initial launching pad for this new role is the “Nullifier Party,” the brainchild of the planter elites in South Carolina, who will subsequently be called “fireeaters” for their fierce anti federalist, pro-slavery activities.

Of all the original Southern states, South Carolina is most dependent on slaves for its wealth, and therefore most protective of any federal threats to the institution.

Its values are established at the 1787 Convention by founder John Rutledge, known as “The Dictator,” who chairs the “Committee of Detail,” charged with defining the exact powers of the legislature. Along the way, he makes it crystal clear that South Carolina will resist any federal intrusions related to slavery.

I would never agree to give a power by which the articles relating to slaves might be altered by the States not interested in that property and prejudiced against it.

The state itself prospers throughout the colonial and post-Revolutionary War period, forming large plantations, relying on slave labor to bring in a range of crops, initially rice and then cotton. The shape of its population is also unique in that slaves make up some 53% of the total residents – a fact that constantly causes fear of rebellion among its white masters.

By the 1820’s, however, economic conditions in South Carolina have taken a turn for the worse.

The state is hard hit by the 1819 depression, and by increased competition from plantations in the new west, operating on more fertile, higher-yielding soil.

Thus the Tariff of 1828 represents one more blow to future prosperity – both for its short-run effect on cotton prices and its potential long-run threat of federal dictates on slavery per se.

For some leading politicians, John Calhoun’s “South Carolina Exposition and Protest” of 1828 represents the proper response to any federal laws that are clearly damaging to an individual state.

Simply pass a state bill “nullifying” them.

Out of this principle, the “Nullifier Party” is born.

It does not spring from immediate, unanimous agreement in South Carolina. In fact, after Calhoun’s document is circulated, roughly half of the state’s politicians argue that ignoring federal laws has already been proven to be unconstitutional.

But the “Unionist” faction finally gives way to the prominent South Carolinians who form the core of the Nullifier Party – Calhoun, along with Robert Hayne, James Henry Hammond, William Preston, George McDuffie, Henry Pinckney, Francis Pickens, and Franklin Elmore.

In 1830, Calhoun declares straight out that the South’s “peculiar domestick (sic) institution” puts it permanently at odds with the majority of the Union, and that, unless it exercises its rights under the Constitution to resist unfair taxation and appropriations, the end will be either civil war or wretchedness.

I consider the tariff act as the occasion, rather than the real cause of the present unhappy state of things. The truth can no longer be disguised, that the peculiar domestick [sic] institution of the Southern States and the consequent direction which that and her soil have given to her industry, has placed them in regard to taxation and appropriations in opposite relation to the majority of the Union, against the danger of which, if there be no protective power in the reserved rights of the states they must in the end be forced to rebel, or, submit to have their paramount interests sacrificed, their domestic institutions subordinated by Colonization and other schemes, and themselves and children reduced to wretchedness

With the 1832 election looming, the “Nullifiers” must settle on a Presidential candidate.

Jackson has already made it clear that he opposes any attempts by individual states to disobey federal laws. Meanwhile Henry Clay is still associated with JQ Adams and is touting his new Whig Party which includes Federalist-like spending on infrastructure that the “Nullifiers” oppose. This leaves Calhoun as the most likely candidate, but he is too wily a politician to cast his lot with what looks like a fringe faction within the Democrat Party.

In the end, the party nominates 47 year old John Floyd, a former medical doctor and now sitting Governor of Virginia. Floyd is an ally of Calhoun, although much less outspoken on slavery than on Jackson – whom he regards as a “tyrant usurper” risking domestic war by denying the sovereign power of the states.

September 1830

Thurlow Weed Founds The Anti-Masonic Party

Another figure intent on bringing Jackson and the Democrats down is the New Yorker, Thurlow Weed.

Weed is the proverbial self-made man. He grows up on his father’s struggling farm in Cairo, NY, which leaves his family “always poor, sometimes very poor.” At age 8 he works for a blacksmith for 6 cents a day; at 10 he earns his “first shilling” as a cabin boy on a Hudson River sloop, with repeat visits to NYC; at 12, he becomes a printer’s apprentice in the village of Catskill; at 16 the quartermaster sergeant of the 40th NY State Militia in the War of 1812; at 18 a journeyman printer for the Albany Register, for $16 a week.

Soon thereafter he begins to write editorials favoring Federalists, particularly NYC Mayor DeWitt Clinton. He slides into politics as a member of the New York State Assembly and helps JQ Adams achieve victory of Andrew Jackson in the “corrupt bargain” election of 1824.

During this period, Weed also meets William Seward and forms a lifelong bond that links them politically over the next half century. Both men strongly oppose slavery, while shying away from abolitionary zeal.

When “King Andrew” wins in 1828, Weed searches for issues that might attract enough public support to mount a credible attack on the dominance of the Democrats.

His first attempt springs from a mysterious 1826 incident in the western New York town of Batavia that quickly captures the public imagination.

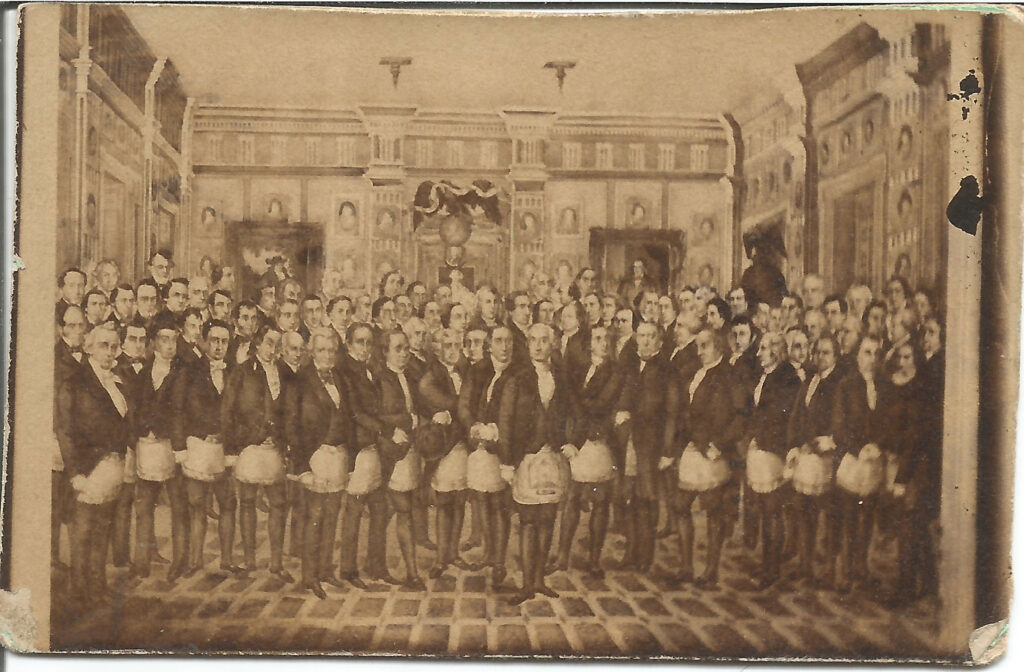

A man named George Morgan is denied membership in a local Free Mason Lodge, and threatens to publish a book revealing its inner workings and secret protocols. He is then evidently kidnapped, and a body, arguably his, eventually washes up on the shore of Lake Ontario.

When Morgan’s book – Illustrations of Masonry – comes out, it paints a picture of a secret society that appears philanthropic, while actually being controlled by “Jesuits and Illuminati who worship Lucifer.” It becomes a best seller, and advances a storyline whereby Morgan becomes an American martyr whose right to free speech is denied by a Masonic order bent on undermining Christian religious values.

In 1828, Weed seizes upon the “Morgan Affair” and translates it into a political attack on any and all Masons serving in government.

He ignores the fact that George Washington was a renowned Mason, because his true target is “Brother” Andrew Jackson — proud member of St. Tammany Lodge #1 in Nashville, Tennessee since 1800, and an eventual Master of Masons.

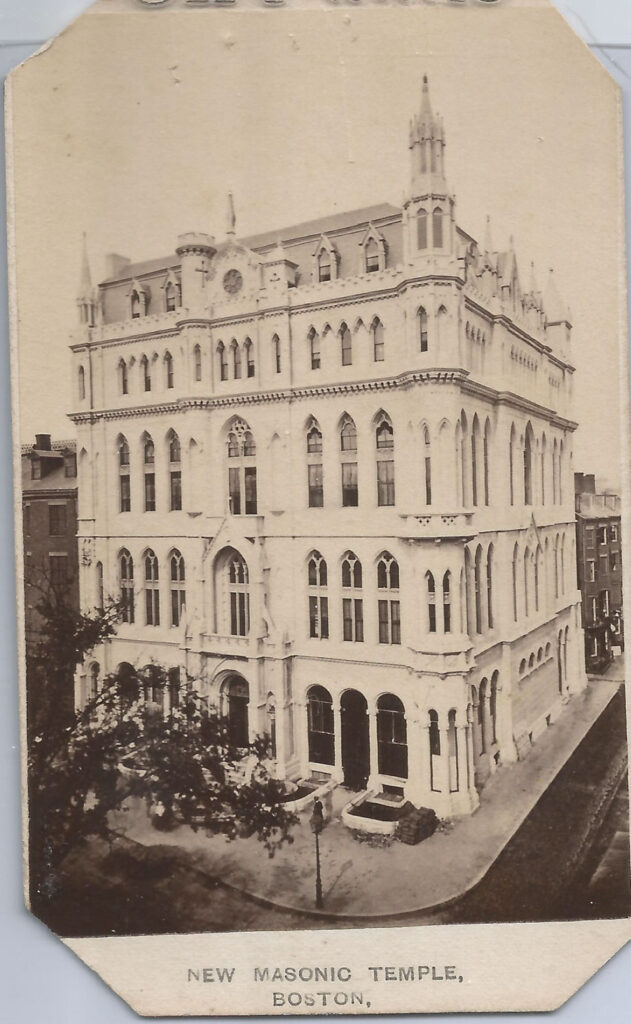

To vilify Jackson, Weed launches a newspaper, The Rochester Antimasonic Enquirer, and forms a new political movement he names The Anti-Masonic Party. Its intent is to exploit two themes that will endure over time with a sizable segment of American voters:

- Fear that everyday citizens may be losing control of their government to secret cabals manipulating policies to satisfy their own separate agendas; and

- Growing resentment against Southern slave-holder dominance in national politics, symbolized at the moment by Andrew Jackson of Tennessee

It argues that all Free Masons must be expelled from public office because their goals and loyalties lie with a secret society whose values conflict with American democracy.

On September 11, 1830 – the anniversary of Morgan’s abduction – Thurlow Weed convenes America’s first full-fledged “nominating

convention” to build a party platform and discuss a potential slate of candidates.

At a second gathering a year later, delegates settle on William Wirt as their presidential candidate. Wirt is a lawyer who gained fame for prosecuting Aaron Burr for treason in 1807 and then for serving as Attorney General under Monroe and JQ Adams from 1817 to 1829.

But he is also a deeply flawed choice — as a former Mason himself, a Southerner from Virginia, and a reluctant candidate who tries repeatedly to back out of the nomination.

Other political figures drawn to Weed’s movement include Henry Seward, Thad Stevens and John McLean.