Section #16 - Open warfare in “Bloody Kansas” follows fraudulent election wins for Pro-Slave State forces

Chapter 188: Filibusterer William Walker Seizes The Nation Of Nicaragua

December 29, 1854

Some 2,800 miles south of Kansas events during the Fall of 1855 are playing out in the country of Nicaragua that further testify to Pierce’s inaugural promise to avoid “timid forebodings” about geographical expansion.

The stars upon your banner have become nearly threefold their original number…(and) the policy of my Administration will not be controlled by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion. Indeed, it is not to be disguised that our attitude as a nation and our position on the globe render the acquisition of certain possessions not within our jurisdiction eminently important for our protection, (and) for the preservation of the rights of commerce and the peace of the world.

Once again it is the filibusterer William Walker who picks up the banner of “manifest destiny,” despite his failed attempt to create the Republic of Lower California in May 1854. This time his target is the Central American nation of Nicaragua.

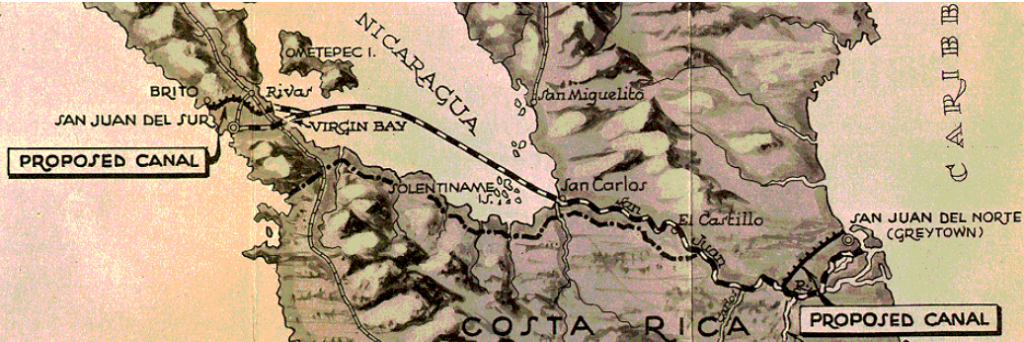

As with Mexico, the U.S. has long had its acquisitive eye on Nicaragua, given the potential to build a canal across its southern border connecting the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, hence New York City to San Francisco. In 1849 the shipping tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt finalizes a deal with the government whereby his “Accessory Transit Company” is given an exclusive “right of way” charter for the canal. While exploration begins, Vanderbilt creates a thriving overland-steamboat route between San Juan del Norte on the east coast and San Juan del Sur on the west.

The country is small, with a population of only 260,000, dominated by those of mixed Indian Spanish blood, along with a smattering of whites and blacks. Since winning its independence from Spain in 1824, it is plagued by civil wars pitting the “white ribbon” Legitimists, the aristocratic party based in Grenada, against the “red ribbon” Democrats, headquartered seventy miles west in Leon.

After suffering a string of defeats, the Democrats approach Byron Cole, an American journalist and friend of William Walker, with an offer to enlist up to 300 mercenaries to fight on their behalf, in exchange for military pay and subsequent land grants.

On December 29, 1854, Walker signs a contract with the Democrats. For the next four months he seeks, and gets, approval to proceed from U.S. commanding General John Wool, then goes about lining up funds (with help from Pierre Soule of “Ostend” fame), arms (aided by the financier, George Law), a transport ship, and initial recruits. Along the way he fights the fourth duel of his life, receiving a wound in the foot.

October 13, 1855

Walker Invades And Wins A Strategic Victory At The City Of Grenada

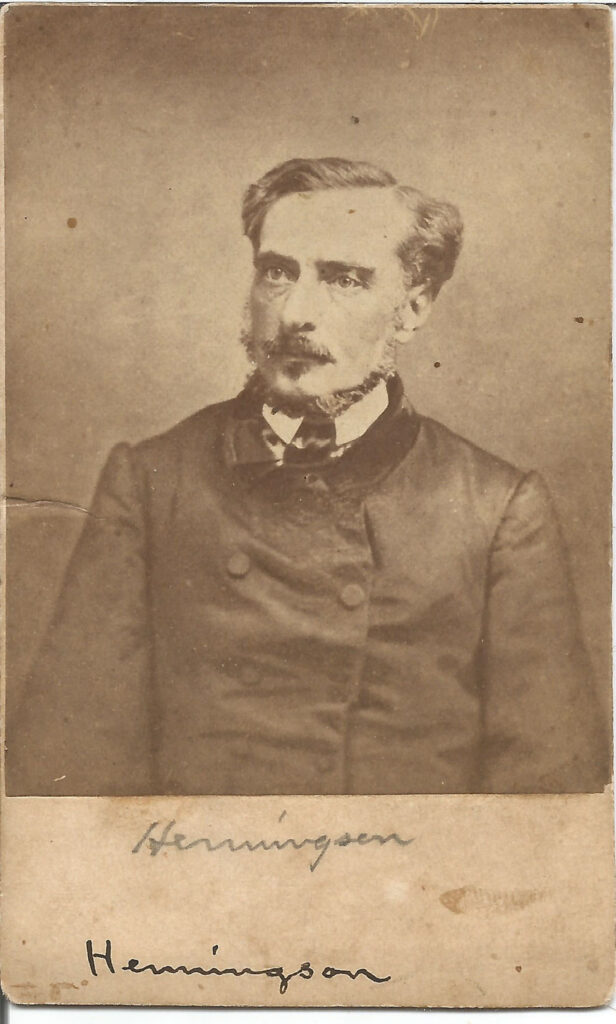

To address some of the flaws in his failed Mexican venture, Walker signs on several experienced mercenaries, including Prussian cavalryman, Bruno Von Natzmer, and Charles Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of combat in Spain, Hungary and Russia. Henningsen will serve as Major General and chief artillerist in Walker’s Nicaraguan army.

The lead contingent of sixty troopers depart from San Francisco on May 3, 1855, travel some 3500 miles by sea, and land on June 16 at the port of Realejo. They are joined by 110 local fighters and head to Leon, where Democrat President Francisco Castellon greets them, confers citizenship, and encourages immediate action. Another voyage takes them just north of San Juan del Sur, where Walker plants himself at the western end of Vanderbilt’s “Transit Company” route, a strategic asset that will supply him with American volunteers over time.

His army is known as the Falanginos (Phalanx) and its first encounter with the Legitimistas occurs at noon on June 29, 1855 at the town of Rivas. As soon as shots are fired, Walker’s local recruits flee, leaving him outnumbered ten to one. Still the American troops perform well before being forced to retreat, with losses of five killed and twelve wounded. Walker blisters Castellon for the cowardice of the Democrat troops and pauses to plan his next steps.

Castellon wants him to conquer the Legitimista capital at Grenada, but Walker prioritizes completing his seizure of the “Transit Company” route between San Juan del Sur and Virgen Bay. He marches east to the Bay, but is then attacked from behind by the enemy on September 2, 1855. With backs up against Lake Nicaragua, his troops win their first important victory at La Virgen, an outcome that boosts his future recruiting and his financial support, especially from Vanderbilt’s firm.

This leads to Walker’s greatest military triumph, a clandestine night voyage with some 250 men up Lake Nicaragua, followed by a successful attack on the Legitimista’s undermanned garrison in Grenada. The date is October 13, and it marks the beginning of Walker’s control over the country of Nicaragua.

On October 22, 1855, he executes the top Legitimista official in Grenada to establish his authority, then gathers the two warring factions together to form a coalition government. He chooses Patricio Rivas as puppet-president, with himself as de facto ruler, heading the Army.

Henceforth his press persona becomes that of “Colonel Walker, the grey-eyed man of destiny.”

December 8, 1855 to May 14, 1856

President Pierce Wavers On Walker’s Filibuster

Franklin Pierce responds to Walker’s activity in Nicaragua with typical equivocation.

After Walker takes Grenada in October, he issues a message condemning the action on December 8, 1855.

But Walker perseveres, sending a series of potential “Ambassadors” to Washington in search of official recognition for his government. The first is the notorious confidence man and gunslinger, Parker French, who is rebuffed in January and then again in February, 1856. Secretary of State William Marcy is particularly outspoken at the time, saying that neither French not Walker represent the will of the Nicaraguan public.

Walker counters by claiming that his patriotic efforts to expand America’s borders is being hampered by the rejection of his chosen minister. This increases the political heat on Pierce as does the glowing praise showered on Walker by former Democratic presidential nominee, Lewis Cass:

The difficulties which General Walker has encountered and overcome will place his name high on the roll of the distinguished men of his age. . . . Our countrymen will plant there the seeds of our institutions, and God grant that they may grow up into an abundant harvest of industry, enterprise, and prosperity. A new day, I hope, is opening upon the States of Central America.

Walker’s next move tells of his own political acumen. He proposes none other than the Curate of Grenada, Father Augustin Vijil, as his designated envoy to Washington – and Pierce agrees to accept him on May 14, 1856.

The next day the President sends his rationale to Congress, saying that the best interests of the nation require him to recognize some government in Nicaragua, and Walker’s Father Vijil is the only option he has.

After his reception, Ambassador Vijils is largely shunned in Washington, and resigns after two months, on June 23, to return to his church duties at home. But he has served Walker’s purpose and forced Pierce to exhibit some official support for the regime.

Once again, the President’s popularity suffers in response to this action. Southerners see his support for expansion into Nicaragua as lukewarm; Northerners and abolitionists see him eventually pandering to the “Slave Power;” Know-Nothings fear another source of Catholic immigrants arriving this time from Central America.