Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 178: Filibusterer William Walker Attempts To Create A Republic Of Lower California

1845-1860

Filibustering Campaigns Seek To Expand America’s Borders

While U.S. diplomats are attempting to complete the “Gadsden Purchase” by peaceful means, a hostile take-over of additional Mexican land is under way, led by the notorious adventurer, William Walker.

The template for intrusion unto foreign soil is set by the founding of the Republic of Texas in 1845. This involves a relatively small band of adventurers who achieve “squatter sovereignty” over a poorly defended territory in Mexico, and then attract a sufficient number of additional recruits to fight off all attempts to dislodge them by force. With that accomplished, admission to the United States was sought and eventually granted.

From the Texas success, the notion of heroic foreign conquest enters the imagination of others, driven by the wish for personal fame and wealth, and, perhaps, the chance to “add another star” to the American flag.

In the lexicon of the time, these individuals become known as “filibusterers,” from the Dutch word “freebooters.”

The Venezuelan born Narciso Lopez earns this title in 1845 when he attempts to conquer Cuba, with support from U.S. Senator John Quitman of Mississippi, an early member of the pro-slavery Southern “fire-eaters.” President Zachary Taylor opposes Lopez’s efforts, and they end when he is garroted to death in Havana.

But the most infamous of all filibusterers is one William Walker, whose exploits between 1853 and 1860 reflect the extent to which “manifest destiny” is embedded in America’s consciousness at the time.

1824-1860

Sidebar: A Profile Of Filibusterer William Walker

William Walker is a precocious youth who graduates at fourteen from the University of Nashville before traveling to Europe to study medicine in Scotland and Germany. He returns to finish his medical degree at nineteen from the University of Pennsylvania, then practices briefly before moving to New Orleans, where he passes the bar and also takes up journalism, as editor of a newspaper, the New Orleans Daily Crescent.

After his purported fiancé dies during a yellow fever outbreak, Walker departs for California during the gold rush, but not before assaulting a fellow writer for articles he finds personally offensive.

In 1849, while working at the San Francisco Herald, he earns local fame by criticizing an unpopular district judge for his court record on crime, then serving successfully as his own attorney after the judge throws him in jail.

His naturally combative personality also resurfaces in a series of three duels. Included here is one with the noted lawyer and gunslinger, William Hicks Graham, who calls him out on behalf of a friend and wounds him severely in the thigh before Walker even gets off a shot.

But Walker is undeterred by this or any other setbacks. In 1851 he is only twenty-seven years old and has tested himself across a remarkable string of careers and events. The time has come for him to tackle another new adventure, to fulfill his destiny on a larger stage. By happenstance, he is presented with a chance to create his own personal empire in a foreign land.

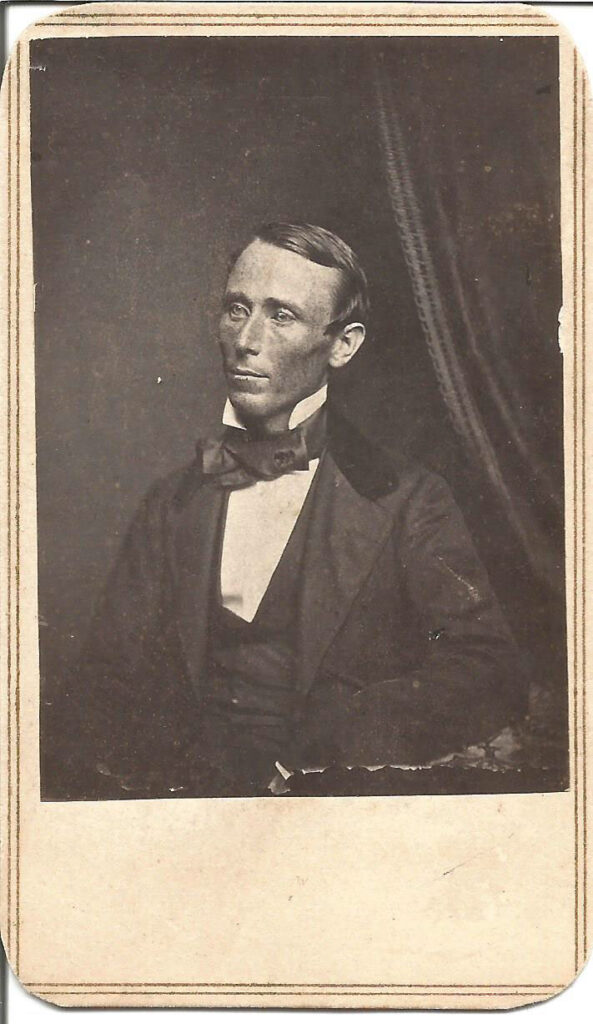

Many who see Walker from afar are unimpressed by his frail, almost feminine appearance and his quiet manner. Others who are closer up recall his “grey, cold eyes” and a personal magnetism that peg him as “no ordinary person.”

His appearance was anything else than a military chieftain. Below the medium height, and very slim, I should hardly imagine him to weigh over a hundred pounds. His hair light and towy, while his almost white eyebrows and lashes concealed a seemingly pupilless, grey, cold eyes, and his face was a mass of yellow freckles, the whole expression very heavy. His dress was scarcely less remarkable than his person. An insignificant-looking specimen.

But anyone who estimated Mr. Walker by his personal appearance made a great mistake. Extremely taciturn, he would sit for an hour in company without opening his lips; but once interested he arrested your attention with the first word he uttered, and as he proceeded, you felt convinced that he was no ordinary person.

Walker remains forever a serious man, intent on accomplishing his ambitious goals, not simply a wild-eyed buccaneer. One observer offers this profile:

Throughout the many vicissitudes of his career Walker always remained quiet and imperturbable. Success never turned his head; failure never caused him to despair. He was as calm under fire as ever he was in the sanctum of the editor or the office of the advocate. His manner was always characterized by extreme simplicity…In spite of his lack of affectation Walker was a great stickler for the dignity of his office… He won no man’s affection, but every man’s respect.

October 1853 – May 1854

William Walker’s Attempt To Annex Lower California Ends In Failure

Ensenada & The Province of Sonora

The happenstance that brings William Walker into the filibustering arena in 1852 is a visit with travelers just back from the port city of Guaymas, in the Mexican province of Sonora. The picture they paint is of territory ripe for silver prospectors, beset by tribal raids, and largely absent any basic civic authority.

Walker processes this information and decides to approach the provincial Mexican governor in June 1853 with a proposition to establish a settlement there in return for acting as a police force to suppress future tribal uprisings. Despite support from the American ambassador, the Mexicans are fearful of the proposal and quickly send him home.

But Walker exits with a conviction that even a small contingent of armed Americans could easily march into Sonora and grab whatever territory they chose to conquer. With this in mind, he begins to recruit his own army, set to invade in the summer of 1853.

He is described as “insanely confident of success” when his small band of 45 troops depart from San Francisco aboard the brig Caroline on October 16, 1853. Given their limited strength, Walker has decided to enter Lower California before moving onward to his main goal, the province of Sonora. The voyage takes him some 1500 miles to the southern tip of the Baha at Cabo San Lucas.

From there he marches overland for 100 miles to the provincial capital of La Paz, where he arrests the local Governor, hauls down the Mexican flag, and declares his control over the new “Republic of Lower California.”

A series of proclamations follow, including one that his Civil Code will conform to that in place in the U.S. state of Louisiana – which includes the practice of slavery, banned in 1828 by the Mexican government.

But Walker’s hold on his new “empire” is fragile. On November 9, 1853, gunfire is exchanged for the first time with hostile forces, and he abandons La Paz for a brief return to Cabo San Lucas before a 1,000 mile exodus to Ensenada, near the California border. Once there he is able to arrange for another 230 American recruits, although they arrive without military gear, and are unable to participate in a minor skirmish with Mexican troops on December 29, 1853.

Favorable publicity about his exploits in California papers translates into prospects for even more volunteers. This further emboldens Walker, and on January 18, 1854 – without moving beyond his current garrison — he declares himself titular head not only of Baja, but also Sonora.

What follows, however, is profoundly disappointing to Walker. His plans to actually govern the new Republic are captured on paper, but he never has the capacity to execute them in practice. His supporters are fighters, not administrators, and their staying power is soon tested. As inaction replaces adventure and basic supplies, even food, begin to run out, signs of mutiny materialize. Walker responds by asking all to swear an oath of loyalty, and those who refuse are told to depart. Soon his total force dwindles to some 130 men, hardly enough to withstand a serious assault, much less govern a territory.

In January 1854, a Mexican warship blocks the port of Ensenada, further threatening his resources — and a visit from the USS Portsmouth, offers Walker no encouragement about aid. Still he perseveres. He moves 50 miles south to San Vicente, arriving there on February 17. He shoots two deserters before setting out on March 20 with his dwindling forces to finally enter the Sonora province he has already claimed. But this journey proves disastrous, with Walker spending three days there before retreating to San Vicente, where he finds his garrison wiped out by the Mexicans.

With no options left, the filibuster comes to an end. Walker and thirty-three remaining stragglers head north to the border and are taken into custody by U.S. authorities at Tia Juana on May 8. They are charged with violating the 1794 Neutrality Act and paroled to San Francisco.

There, after a complicated trial in Federal Court — with Walker again participating as a defense attorney – a jury amazingly acquits him of all charges, reportedly after only eight minutes of deliberation.

Instead of ending up in prison, William Walker leaves the court a free man and a folk hero. His first attempt at filibustering has failed, but before long he will be back to try it again.