Section #13 - The 1850 Compromise has Democrats backing “popular sovereignty” voting instead of a ban

Chapter 157: Douglas Drives His 1850 Compromise Bills Through Congress

July 1850

Texas Tries To Extend Its Borders Into New Mexico

Within a few days of taking office and dismissing Taylor’s cabinet, Texas decides to challenge the new President.

They do so by a demand from Governor Peter Bell to extend the boundary of his state west to the city of Santa Fe in the New Mexico Territory.

Given that Texas is a designated “Slave State,” this would extend the institution even further to the west.

This demand is not new.

Former President Taylor’s response to it has been unequivocal — including a promise to personally lead U.S. troops against any Texas incursions, and, if they occur, to call for the immediate admission of New Mexico as a Free State.

Fillmore’s response is to vacillate.

At first he orders 750 more soldiers to the border as an apparent show of strength. From there he backpedals, evidently for fear of losing support in the South.

He begins by blocking the attempt by New Mexico to apply immediately for statehood, knowing that the settlers there are signaling their intention to become a “Free State.”

He then supports a bill to set up a commission to study the boundary lines – rather than act upon them as proposed in Clay’s Omnibus Bill.

With every hesitation here aimed at appeasing the Texans and the South, Fillmore contributes to the steady unraveling of Clay’s attempted compromise.

July 22, 1850

Clay’s Dire Warning Fails To Pass His Omnibus Bill

Henry Clay makes a final attempt to pass his Omnibus Bill on July 22, 1850, in a speech to the Senate.

His words are highly charged and stark. They represent a warning to Northerners who wish to admit California immediately as a Free State and also outlaw slavery in the remainder of the Mexican Cession territories. The result, according to Clay, will be a sense of betrayal across the South, leading on to violence, secession and war.

As owner of the Ashland plantation and some sixty slaves, Clay

understands the dire economic implications for the South of a totally “Free State” outcome in the west – and he begins his address in this vein. Preserving the Union requires preserving “fraternal commercial ties” between the North and the South.

There are two descriptions of ties which bind this Union and this glorious people together. One is the political bond and tie which connects them, and the other is the fraternal commercial tie which binds them together. I want to see them both preserved.

These economic ties will be broken if all the Senate does right now is to admit California as a free state. The likely response will find the Southern states (and perhaps Missouri) sending an army into the New Mexico Territory, to make it a part of Texas and to institutionalize slavery.

Before the autumn arrives, troops may be on their march from Texas to take possession of the disputed Territory of New Mexico, which she believes to belong to herself.

Is this not a danger which should make us pause and reflect, before we leave this capitol without providing against such a perilous emergency?

Let blood be once spilled in the conflict between the troops of Texas and those of the United States, and thousands of gallant men will fly from all the slaveholding States, to sustain and succor the power of Texas, and to preserve her in possession of that in which they, as well as she, feel so deep an interest.

Once blood is spilled in New Mexico, he feels the South will be led “by a patriotic zeal to defend itself against Northern aggression.” Without the Omnibus Bill, the outcome will be secession and war.

For, sir the admission of California alone, under all circumstances of the time, with the Wilmot proviso still suspended over the heads of the South, with the abolition of slavery still threatened in the District of Columbia… the act of the admission of California, without provision for the settlement of the Texas boundary question, without the other potions of this bill, will aggravate, and embitter, and enrage the South, and make them rush on furiously and blindly, animated, as they believe, by a patriotic zeal to defend themselves against northern aggression

I call upon you, then, and I call upon the Senate, in the name of the country, never to separate from this capitol, without settling all these questions, leaving nothing to disturb the general peace and repose of the country.

Among those standing in the way of compromise are the Abolitionists, like John Hale, whose “vocation” rests on creating agitation around slavery.

There is not an abolitionist in the United States that I know of that is not opposed to this bill. And why are they opposed to it? They see their doom as certain as there is a God in heaven who sends His providential dispensations to calm the threatening storm and to tranquillize agitated man. As certain as that God exists in heaven, your business [turning toward Mr. Hale], your vocation is gone.

If war begins, Clay believes the outcomes will be unknown and likely to differ from the hopes of either side.

If there should be a war…history teaches, that the end of war is never seen in the beginning of war, and that few wars which mankind have waged among themselves, have ever terminated in the accomplishment of the objects for which they were commenced.

Instead of war, he says the “nation wants repose” and that passage of his bill will represent a “reunion of this Union,” the same return to the tranquility that followed the 1820 Missouri resolution.

The nation wants repose. It entreats you to give it peace and tranquility. If you adopt the measures under consideration, they, too, will be followed by the same amount of contentment, satisfaction, peace, and tranquility which ensued after the Missouri compromise. I believe from the bottom of my soul, that the measure is the re-union of this Union. I believe that it is the dove of peace, which, taking its aerial flight from the dome of the capitol, carries the glad tidings of assured peace and restored harmony to all the remotest extremities of this distracted land.

In conclusion, Clay begs his fellow senators not to “go home doing nothing.” To do so would be to risk being “condemned by our own consciences, constituents, and country.”

Let me, Mr. President, in conclusion, say that the most disastrous consequences would occur, in my opinion, were we to go home, doing nothing to satisfy and tranquillize the country upon these great questions.

Sir, we shall stand condemned by all human judgment below, and of that above it is not for me to speak. We shall stand condemned in our own consciences, by our own constituents, and by our own country.

Let us go to the fountains of unadulterated patriotism, and, performing a solemn lustration, return divested of all selfish, sinister, and sordid impurities, and think alone of our God, our country, our conscience, and our glorious Union. These are my sentiments.

This July 22, 1850 address represents the seventy-three year old Clay’s last best effort to intervene once again in the “slavery question” – and to assert his leadership position within his beloved Whig Party.

But his effort ends in failure on both counts.

The forces lined up against him are too formidable this time. They include a wide swath of Southerners, from the Fire-Eaters of South Carolina to the generally more moderate senators like Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and John Berrien of Georgia. Opposition in the North comes not only from Abolitionists like Hale and Chase, but also from other anti-slavery men, including Henry Seward.

Finally, Clay runs up against Millard Fillmore. Unlike the decisive Taylor who supported Clay’s bill, Fillmore remains cowed by Southern demands and by any possible challenges to his hoped for leadership of the Whig Party.

On July 31, Senate Bill 225 makes its final appearance on the floor. It faces one amendment after another and a string of very close votes on each. In the end, however, a thoroughly exhausted

Henry Clay admits defeat and heads home to Lexington, even though the 31st congress remains in session.

August 1850

Douglas Recasts The Bill To Gain Southern Support

Clay’s departure does not end the need for some resolution in Congress over the admission of California and the search for “off-sets” that are tolerable to the South.

Absent leadership from the Whig President, the Democrat Stephen Douglas steps into the void.

In working with Clay to create the Omnibus Bill, Douglas notices that while slim majorities of Senators favor individual elements within the act, very few sign on for the totality.

Like all accomplished politicians, the pugnacious Douglas is a savvy vote-counter and tactician. He quickly articulates why Clay’s bill has been defeated.

I regret it very much, although I must say that I never had very strong hopes of its passage. By combining the measures into one bill the Compromise united the opponents of each measure instead of securing the friends of each.

On August 1, one day after Clay departs for Kentucky, Douglass tears the Omnibus Bill into five separate parts, and calls upon the “friends of each” to create majorities

Five days later, Fillmore further muddies the water by telling congress that the federal government “has no power or authority” to impose boundary lines in this case absent consent from the Texans – a conclusion that totally astonishes most members, and convinces Northerners that the new President is eager to pander to Southern interests.

With Douglas in charge, what started out as a Whig-driven bill now morphs into one shaped by the Democrats.

August 9- September 20, 1850

Douglas Drives The Measure Through Congress In Pieces

Despite Southern wishes, Douglas cannot guarantee that more “slave states” will materialize in the west. He can, however, derail Taylor’s wish to immediately pass a Wilmot-like ban, and stall Northern momentum toward this objective. He begins to execute his strategy by focusing on Texas.

On August 9, the Senate approves the Texas Boundary Act. It is an outright triumph for the Texans, who have cowed Fillmore into believing they would go to war against federal troops over their border claims. The bill extends the Texans western border to include some 70,000 square miles of land Taylor had assigned to New Mexico (albeit not Santa Fe) and transfers $10 million of the state’s accumulated debts to the federal coffers.

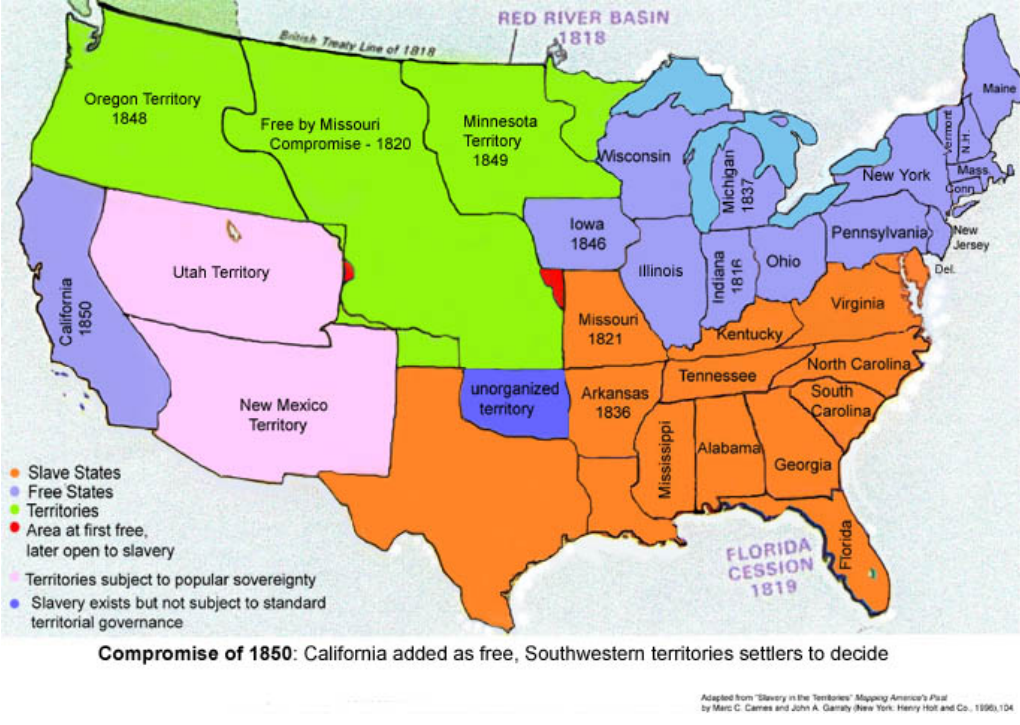

Douglas follows on August 13 by deeding the North its solitary victory, with the admission of California as a free state. This follows defeat of Southern efforts to split the state in two by extending the 1820 Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific.

Next comes the crucial issue of how to handle slavery in the New Mexico and Utah Territories.

Taylor clearly wanted a ban on slavery in both, and the residents of New Mexico have already signaled their wish to become a “Free State” in early constitutional voting. But neither Douglass nor Fillmore intend to risk potential southern support in the 1852 election by such a ban.

Instead Douglas convinces his colleagues to simply freeze both in limbo status for the time being, until a “popular sovereignty” vote can be taken. On August 15, the Senate approves a bill which does just that.

The result being that slavery is momentarily made “legal” across the two new territories – even north of the sacred 36’30” Missouri Compromise line!

This is the first of two major “give ups” to the South by Douglass, later followed by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act which eventually provokes the Civil War. But Fillmore and Douglass are not yet done with their mutual concessions.

What comes next is an updated version of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act, intended to force Northern authorities to take an active role in identifying and returning all run-away slaves in their midst, or suffer heavy duty fines. All 25 Southern senators support the bill, while only three of the fifteen Northerners who “take the vote” agree. From the moment this act goes into effect, it provokes a deepening hostility toward the South, especially in New England.

Finally, on September 20, the initiative to totally ban slavery in the District of Columbia is defeated in favor of a lesser measure to curtail slave trading. But even this is watered down, since it applies only to new slaves brought into DC from outside, while still allowing private sales of those already there.

This is significant to the South in that it again signals the unwillingness of politicians to abolish slavery where it has been entrenched – even though, in federally controlled DC, it has the power under the Constitution to do so.

All votes on these bills are heavily skewed in the Senate along regional lines.

Vote Counts On The 1850 Compromise Bills – In The Senate

| Northerners | Texas Border | California | New Mexico/Utah | DC Slave Trade | Fugitive Slave |

| Yea | 18 | 21 | 11 | 21 | 3 |

| Nay | 8 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 12 |

| Southerners | |||||

| Yea | 12 | 6 | 16 | 6 | 25 |

| Nay | 12 | 18 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

By September 20 President Fillmore has signed all five acts and the Compromise of 1850 becomes the law of the land.

1850 Forward

Net Effects of the 1850 Compromise

A little over one year has passed since President Taylor shocked the South by supporting immediate statehood for California and New Mexico, and promising not to veto a Wilmot Bill if it reached his desk.

In the interim, the South has threatened secession, Taylor has died, Fillmore has vacillated, Clay’s attempts at an all-in-one bill have failed, and Douglas has stepped in to secure the final 1850 Compromise.

Those who favor the 1850 Bills – mainstream Democrats and Southern Whigs – feel that the trade-offs agreed to should resolve the sectional tensions.

But their optimism is by no means shared by other factions.

The Fire-Eater southern Democrats feel that their basic Constitutional rights are still not being protected against threats from the North. California’s admittance creates a 16-15 edge in the Senate for the “Free States” – and future “pop sov” votes in New Mexico and Utah may go against the spread of slavery to the west. Indeed, even Douglas is secretly convinced of that outcome.

Northern Whigs detest the Fugitive Slave Act, with the prospect of being forced to cooperate with Southern “agents” in capturing runaways.

The schizophrenic Free Soilers are likewise disappointed. The abolitionist wing fails to get the ban on slavery it wanted; the white supremacist Wilmot men have no guarantees that all Africans will be kept out of the west.

While tensions remain, there can be no doubt that the South emerges with the much better end of the deal.

Taylor’s plan to admit New Mexico and Utah as Free States (along with California) is stalled. Slaveholders are allowed to bring “their property” into the western territories and settle down. Requirements to capture and return run-aways to the North are stiffened. Texas is granted a large chunk of New Mexico’s land, along with $10 million to pay its debts. The effort to abolish slavery in DC fails, and it becomes clear that, when pushed, Millard Fillmore will give in to pressure from the South.

The North, meanwhile, gets very little. Before the bill, pressures related to the gold rush already made California a shoe-in to join the Union as a Free State. So the only incremental gain lies in a small symbolic agreement to curtail slave trading in DC. But this is a far cry for the Wilmot and anti-slavery Northerners from a complete ban on slavery in the west.

Factions Supporting Or Opposing 1850 Compromise

| Democrats | Votes | Rationale |

| Mainstream | Favor | Support popular sovereignty & holding Southerners in the party |

| Fire-Eater South | Oppose | Feel that the Constitutional rights of the South are violated |

| Whigs | ||

| Southern | Favor | Avoids outright ban on slavery in the west favored by Taylor |

| Northern | Oppose | Give-away to South especially the Fugitive Slave Law |

| Free Soilers | ||

| Anti-slavery men | Oppose | Fails to ban slavery & threatens all runaways |

| White supremacy | Oppose | No guarantees against blacks on what should be white soil |

Thus almost before the ink is dry on the Compromise of 1850 both sides are bemoaning the results.

Like the original 1797 Northwest Ordinance, Henry Clay’s 1820 Missouri Compromise at least gave the nation concrete boundary lines designating where slavery would and would not be permitted, as related to the Louisiana lands.

The 1850 Bill from Douglas and Fillmore fails to achieve comparable clarity – and, as such, the issue simply continues to fester.