Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 200: Disagreement Over “Party Goals” Divides The Know Nothings

February 22-25, 1856

Conflicts Arise Over The Party’s Main Reason For Being

While the Republicans are together for the first time in Pittsburgh, some 227 Native American (Know Nothing) Party delegates attend the first, and what will prove to be their only, national convention, over in Philadelphia.

By the time they meet, their anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic message is no longer confined to secret lodge meetings but is out there in the public eye vying for converts and increased political power.

But the prospect for any such surge collapses almost immediately when an opening day schism materializes between Northern and Southern delegates.

The roots of this schism trace to the 1855 race for Governor of Ohio. It pits Allen Trimble, a 72 year old legend in Ohio politics who decides to run as a Know Nothing, against Salmon P. Chase, a co-founder of the Free Soil Party, which opposes all further expansion of slavery.

When Chase whips Trimble by a 6:1 margin, a leader of the Ohio Know-Nothings named Thomas Spooner concludes that the majority of Northerners actually feel more threatened by the Africans than by the Catholic immigrants – an insight consistent with the state’s long history of race riots and opposition to runaway slaves from Kentucky.

Spooner’s response is to try to drive his Native American Party in Ohio toward a coalition with the emerging Republican Party, which has already declared its opposition to slavery in the west. He is urged on in this direction by Chase himself, who already sees the Republican Party as his path to running for the presidency.

Purists among the Know Nothings oppose this blurring of the party’s original intent to focus on immigrants. The Cincinnati Dollar Times calls this:

An attempt to fasten anti-slavery as an issue on to the American Party.

The Ohio Eagle regards it as a sell-out to the Abolitionists:

The great American Party sold body, boots and britches to the nigger-stealing Abolitionists.

Despite this resistance, the Ohio delegates show up at the national convention on February 22 demanding that the presidential nominee repeal the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act and end the possibility of slavery taking root above the old 36’30” Missouri Compromise line.

The vote on the proposed Ohio plank becomes a litmus test for those in the American Party. All stand together in opposition to the Catholic immigrants, but how many are willing to also oppose the spread of those “other foreigners,” the Africans?

When the ballots are counted, the Ohio slavery proposal goes down to defeat – followed by a motion offered up to oust the State’s original representatives from the hall.

This outcome so angers roughly fifty Northern delegates, from New England through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and Iowa, that they decide to walk out in protest.

With them goes any possibility for continued unity within the American Party.

February 22-25, 1856

The Depleted Know-Nothings Select Millard Fillmore As Their Nominee

Those delegates who remain in Philadelphia are left with the challenges of finalizing a national platform and choosing a presidential ticket.

Given their skew now toward the Southern states, all issues related to slavery are swept aside.

Instead the party circles back to its central theme – “Americans must rule America.”

The platform itself consists largely of philosophical slogans, aimed at defending the “True Americans” — native born Protestants — from threats posed by the Catholic immigrants. The litany includes:

Our Country, our whole Country, and nothing but our Country.

American Constitutions & American sentiments

The doctrines of the revered Washington

American Laws, and American legislation

None but Americans for office.

A pure American Common School system.

Opposition to the formation of Military Companies, composed of Foreigners

The amplest protection to Protestant Interests.

The advocacy of a sound, healthy and safe Nationality

Formation of societies to protect American interests

War to the hilt, on political Romanism.

Hostility to all Papal influences, when brought to bear against the Republic

Eternal enmity to all those who attempt to carry out the principles of a foreign Church or State

Death to all foreign influences, whether in high places or low!

More stringent & effective Emigration Laws.

The sending back of all foreign paupers

Repeal of all Naturalization Laws

After passing the platform, attention returns to choosing a ticket for 1856. The walk-out by the eight Northern delegations seems to call for a presidential candidate who will be credible above the Mason-Dixon line, while also remaining sympathetic to Southern interests.

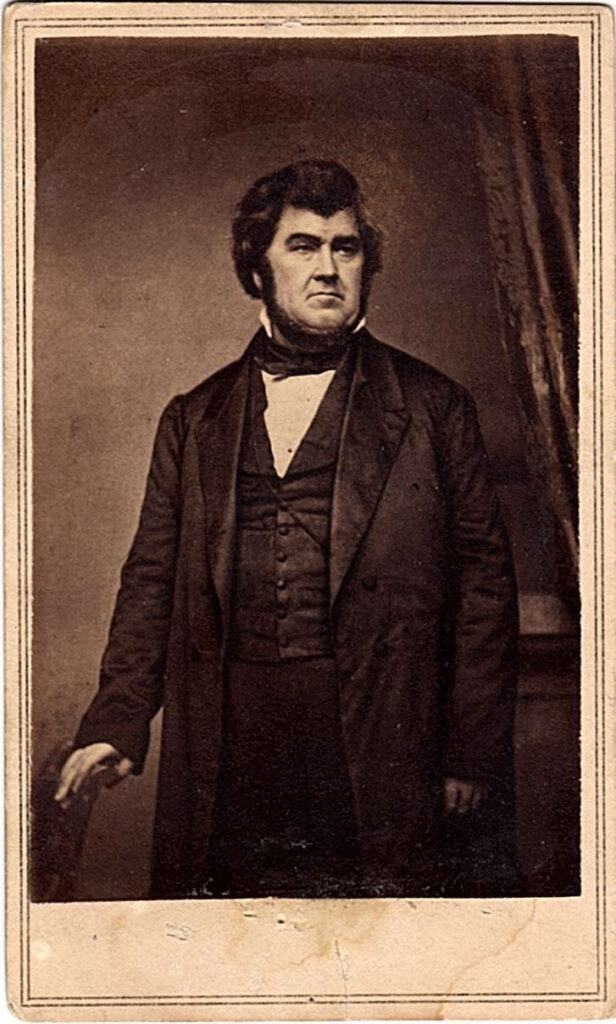

The choice comes down to a battle within the New York delegation, which remains in the hall when other Northern states have bolted. On one side are those who support ex-President Millard Fillmore, despite his very thin history of nativist pronouncements. On the other are backers of Fillmore’s bitter enemy, George Law, a bearish figure whose great wealth derives from his construction, steamship and railroad companies. Law is also endorsed early on by James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Daily Herald, and vocal critic of the Pierce administration.

Any uncertainty about the convention’s choice is resolved on the first ballot, with Fillmore enjoying a commanding lead. On the second he goes over the top and becomes the party nominee.

Election Of Know-Nothing Presidential Nominee (1856)

| Candidates | Home State | 1st Ballot | 2nd Ballot |

| Millard Fillmore | New York | 139 | 179 |

| George Law | New York | 27 | 35 |

| Garrett Davis | Kentucky | 18 | 8 |

| Kenneth Rayner | N. Carolina | 14 | 2 |

| John McLean | Ohio | 13 | 1 |

| Others | 23 | 9 | |

| Total | 234 | 234 | |

| Needed (2/3rds) | 157 | 157 |

Fillmore is fifty-six years old when nominated, and has retired to his home base in Buffalo after he loses the Whig nomination for president to Winfield Scott in 1852. His only substantive linkage to the Know Nothing cause in 1856 is a casual observation about the “corrupting influence” of foreigners in American elections.

The Vice-Presidential slot goes to Andrew Jackson Donelson, adopted son of the former President, and a leading figure in Tennessee politics.

Meanwhile a disgruntled George Law is approached by Republicans, eager to win all wavering Know Nothings, Whigs and Democrats into their orbit.

Sidebar: Abraham Lincoln’s Views On The Know Nothings

Abraham Lincoln is one of many Whig Party politicians searching for a new affiliation during the 1850’s. But one thing he knows for sure by 1854 is that he is “not a Know Nothing:”

I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist. When I was in Washington I voted for the Wilmot Proviso as good as forty times, and I never heard of any one attempting to unwhig me for that. I now do no more than oppose the extension of slavery.

I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor or degrading classes of white people?

Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes”

When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy [sic].