Section #1 - America’s years as a British Colony end with The Revolutionary War

Chapter 2: Comes The Scourge Of Slavery To The Colonies

1600 – 1860

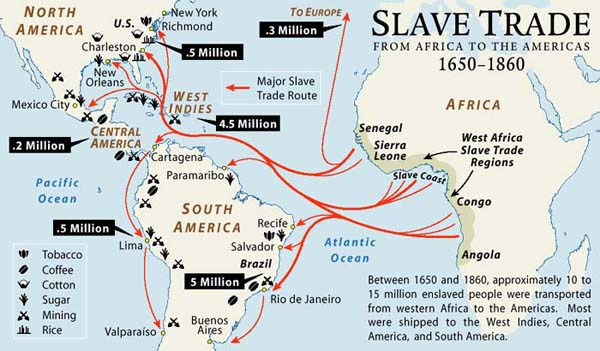

The International Slave Trade Flourishes

Accompanying white explorers to the New World is the practice of slavery common across the world in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Between 1600 and 1800, roughly 11 million blacks are transported from their homes along the west coast of Africa (from Senegal to Angola) to the Americas.

Two nations dominate this market for slaves: the Portuguese, who import 5 million of these Africans for their mining operations and sugar cane fields in Brazil; and the Dutch, who claim another 4.5 million for sugar cane production in the West Indies.

About 500,000 eventually arrive in North America.

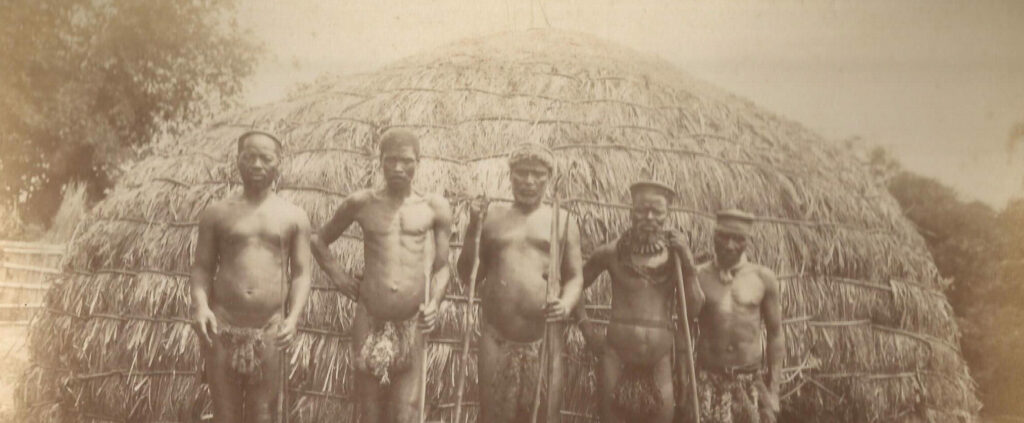

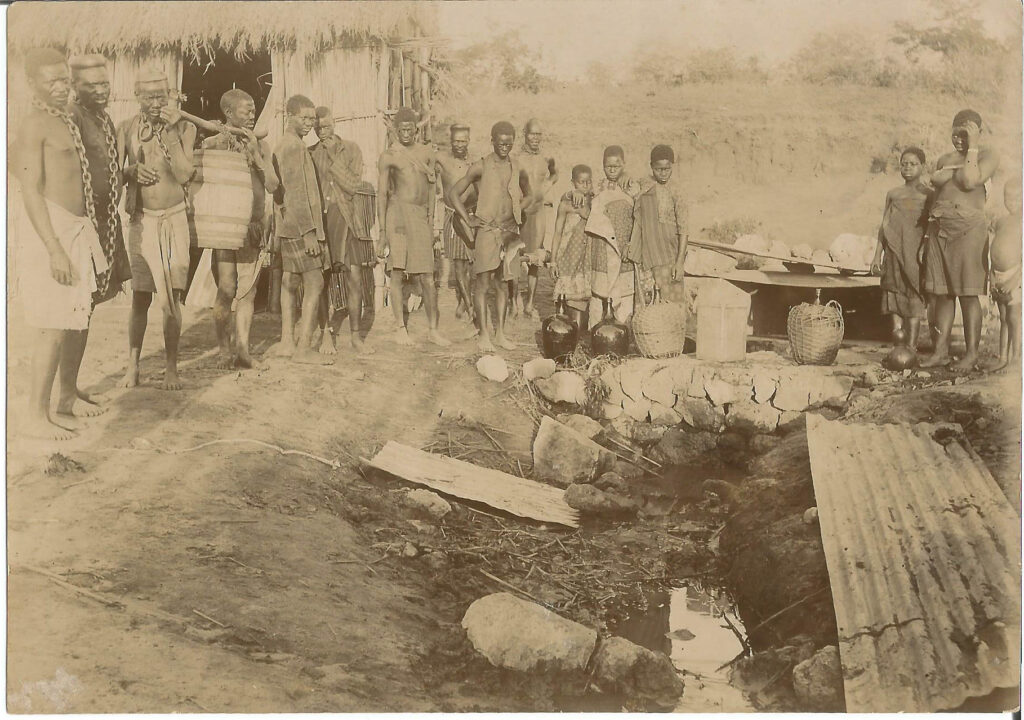

Slave trafficking originates with deals between European agents (“factors/middlemen”) and tribal chiefs, who raid rival villages, round up families, rope them together in “coffles,” and drive them to collection Slave trafficking originates with deals between European agents (“factors/middlemen”) and tribal chiefs, who raid rival villages, round up families, rope them together in “coffles,” and drive them to collection centers, known as “barracoons.”

From there they are packed, 100 at a time, into the holds of ships for the 6 passage” across the Atlantic, where about 15 out of every 100 die in a week “middle route…

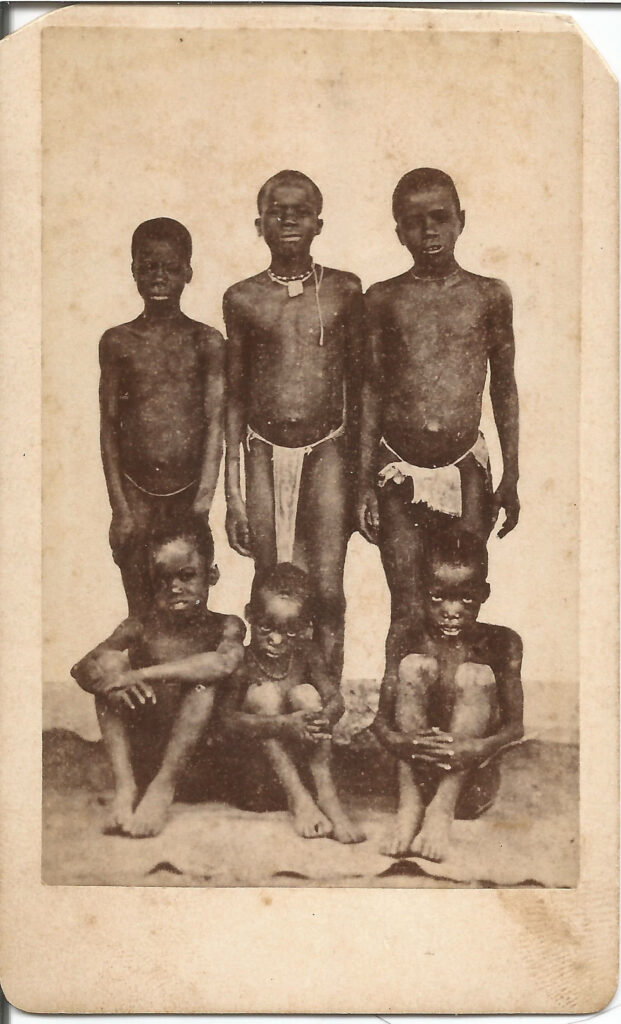

The survivors are stored in pens, “graded and priced,” and then auctioned off to the highest bidders. Strong male field hands one way; their wives and children another.

At that point the slaves became the “personal property” of their owner, to do with as they choose.

1619 – 1750

Slavery Begins In America With Rhode Island As The Trading Hub

The first slaves in America appear at Jamestown colony in 1619, working as field hands on farms, raising tobacco and rice.

Six Enslaved Boys

Six Enslaved BoysIn 1644 an association of Boston traders sends a ship to Africa in search of slaves, and by 1678 a few sales are recorded in Virginia. But it is not until 1700, when the British begin to dominate the Dutch, that New England merch ants see the opportunity to set up a profitable business around the slave trade.

Many of the prominent New England families in colonial America trace their early wealth to the slave trade:

- The Fanuils, Royalls and Cabots Massachusetts;

- The Whipples of NH and the Eastons of Connecticut;

- The Willing and Morris families of Philadelphia;

- The Wantons, Browns, and Champlins of Rhode Island.

It is Rhode Island; however, that controls roughly 75% of the business. In 1740, the port city of Newport is home to some 150 slave ships many run by the four Brown brothers, who found a university bearing their name after making a fortune selling lumber, salt, meat and African slaves.

The British too are heavily invested in the “triangular commerce” between Africa, their American colonies and Europe. So much so that their permanent “slave stations” dot Africa’s west coast ports.

By 1750 then, slavery is a widely accepted and well entrenched institution in America.

Slaves are owned in all thirteen British colonies and they play a critical role in America’s economic growth.

In the South, slaves are used to grow and harvest labor indigo. They are also systematically “bred intensive crops, initially tobacco, rice and indigo ” to produce offspring for sale in the open market.

The early New England economy profits from slaves in several ways:

- Distilleries across the region rely on sugar and molasses imports from slave plantations in the West Indies to make rum – which in turn is distributed across the colonies, and exported, to Europe and Africa.

- The New England shipping industry – from boat builders and sail-makers through sailors and long-shore men and accountants – hinges on cargo that is in global demand, including slaves sent from Africa to Newport, and from there to Southern ports like Savannah and New Orleans.

- Northern textile mills begin to spin raw cotton picked by Southern slaves into yarn and thread, which is then shipped to Britain and France to make clothing and other finished goods.

But these sectional patterns are about to change as America enters the second half of the 18th century.

In the South, the institution of slavery becomes firmly entrenched; in the North it is gradually withering away.

1775 Forward

Slavery Begins To Wither Away In The North

Aunt Fannie of the Lott Household

Aunt Fannie of the Lott HouseholdMeanwhile, in the North, slavery is on its way to disappearing by 1775 – an outcome welcomed by many of that region’s founding fathers.

One of them is the Quaker, Ben Franklin, who calls slavery…

An atrocious debasement of human nature.

Another is Dr. Benjamin Rush, the renowned Philadelphia physician, who assails the institution in his 1773 pamphlet An Address to the inhabitants of the British Settlements in America upon Slave-Keeping. As a scientist, Rush is particularly important for arguing against the widely accepted belief that blacks are inherently inferior intellectually. He is also a lifelong supporter of abolition, calling the practice of slavery…

So foreign to the human mind that the moral faculties…are rendered torpid by it

Franklin and Rush are joined by John Jay, who is serving as Secretary of Foreign Affairs in 1785, when he founds the New York Manumission Society, which endures over the next six decades. The Society first battles to end the slave trade, then in support of abolition, and finally for the education of black children. In 1794 it opens the first African Free School in the city, a one-room facility that reaches some forty students. Over time these Free Schools proliferate widely, and prepare many next generation blacks for assimilation into white society.

But moral concerns fail to explain the decline in northern slavery.

Instead, the reason is simple: by 1775 the slave trade is no longer the profitable business it once was.

After two centuries of abducting healthy young blacks for slavery, tribes living along the west coast of Africa have literally become depopulated…

Which in turn alters the economics for the New England merchants. Sending a ship across the Atlantic is both costly and risky, and returning late or without a full cargo of slaves becomes the unattractive norm.

While the importation of African slaves drags on until it is banned in 1808, the boom profits of 1750 period are long gone by then.

So the Northern colonies look away from the slave trade and toward other industries to sustain their drive for wealth. Fortunately for them, new options are right before their eyes. The “triangular trade” between America, Africa and Europe has taught the North that it can manufacture goods like rum and cotton yarn and use its ships to distribute them across the Atlantic.

Thus the making and selling of goods begins to replace the slave trade in the Northern economy.

By about 1775 it’s clear that the North is no longer committed to slavery for economic reasons, and is instead beginning to question “what to do about both slaves and free blacks” in the future.

1775

The South’s Dependency On Slavery Deepens

The Southern commitment to slavery is evident in population data from 1775.

At that time, there are roughly 500,000 blacks in America — with 90% of them are living in the South.

They comprise 41% of the South’s total population, and in some places, like South Carolina, blacks actually outnumber whites.

Estimated Population Counts by Race in 1775

| Section | States | Whites | Blacks | Total | % Black |

| Lower South | GA, NC, SC | 247,000 | 171,000 | 418,000 | 41% |

| Upper South | VA, MD, Del | 481,000 | 282,000 | 763,000 | 37% |

| Mid-Atlantic | PA,MD,NJ | 462,000 | 30,000 | 492,000 | 6% |

| New England | Con, RI, NH, MA | 621,000 | 19,000 | 640,000 | 3% |

| Grand Total | 1,811,000 | 502,000 | 2,313,000 | 22% |

Their role in the economy of the South is crucial.

While the North is already diversifying and modernizing its economy by 1775, Southern wealth is concentrated almost entirely in two areas.

The first is agriculture, where its favorable climate and coastal access make it uniquely equipped to succeed.

In the upper South, tobacco is the dominant crop; the coastal Carolinas are ideally suited to rice and indigo (used for dyeing); cotton is grown throughout the region, but is not yet the “king” it will become. All of these crops are in popular demand both domestically and internationally, and all are labor intensive to produce.

Profits are maximized through economies of scale – the more one produces, the lower the unit cost and the higher the margin. This in turn leads to the creation of vast plantations across the South, the early precursors of modern agri-business operations.

The labor required to plant, grow, harvest and ship these crops is physically demanding, and it falls on the backs of Southern slaves – especially field hands working from dawn to dusk during peak seasons.

As these plantations yield ever greater profits to their owners, the intrinsic “value” of the slaves themselves increases dramatically, opening up a second vital revenue stream.

This second driver of Southern wealth — its “second crucial crop” – lies in the “breeding and sale” of offspring slaves to growers aspiring to ascend to the planter class.

In effect then, “producing” more slaves becomes an end unto itself.

More slaves translate to more profits, either from greater crop yields to be sold, or from auctioning off one’s excessive inventory – black men, women and children – to other growers.

By 1775, the men of the South – unlike those up North – have their economic futures inextricably bound to the presence and expansion of slavery across the colonies.

Many Southerners think of it, with varying degrees of discomfort, as the “peculiar institution.”

But it is their institution, and they mean to defend it with all their wits and might.