Section #13 - The 1850 Compromise has Democrats backing “popular sovereignty” voting instead of a ban

Chapter 148: Clay And Douglas Offer An “Omnibus Bill” To Assuage The South

January To February 1850

Clay Steps In Again To Search For Another Compromise

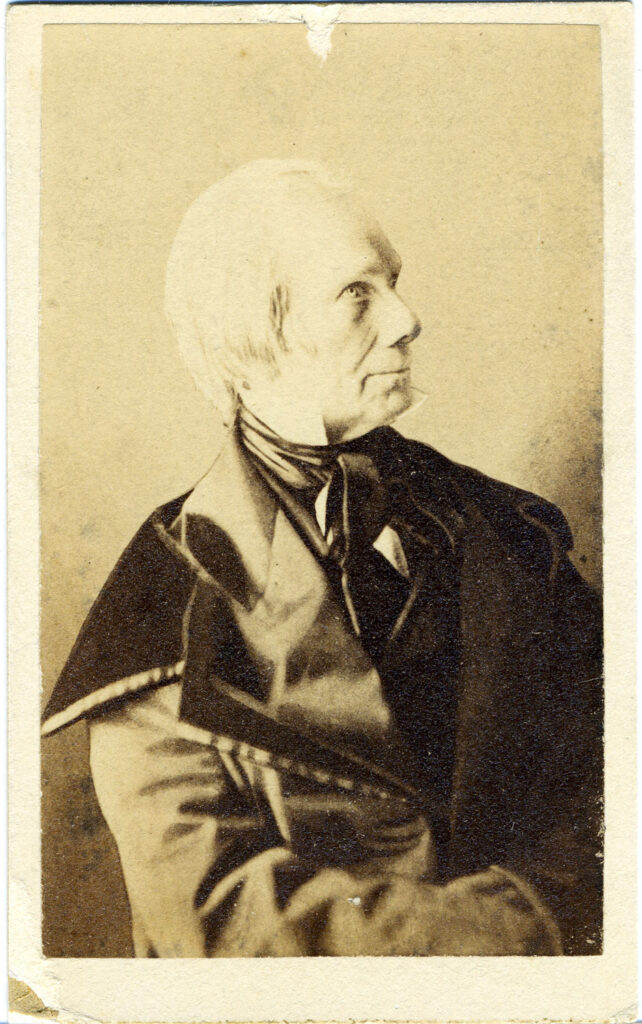

Senator Henry Clay is 72 years old when the crisis over California materializes.

He has been in in various DC posts 43 years, since joining the Senate from Kentucky in 1806. His family life has been filled with tragedy.

All six of his daughters have died young of various diseases, and one of his five sons – Henry Clay, Jr. – has been killed in 1847 at the Battle of Buena Vista, while serving under Taylor. What cruel irony to be called upon to “fix” the consequences of the Mexican War he opposed in congress and that cost him his namesake.

Still Clay is nothing if not a patriot, and he jumps right in.

As a master of legislative horse-trading, he knows that tensions over California entering as a Free State would be greatly reduced if the South could be guaranteed a new Slave State to be carved out of the New Mexico or Utah Territories.

The problem of course is that such “guarantees” are no longer a political option.

Prior votes on the Wilmot Proviso have shown that a majority in the House oppose any extension of slavery in the new West, and President Taylor, the titular head of Clay’s own Whig Party, has said he would support this prohibition.

This leaves the “Great Conciliator” with only one way out – embracing the Democrat’s bandwagon on “popular sovereignty” as a path that could conceivably lead to the admission of more Slave States, to offset California.

While hardly the “federal guarantees” wanted by the South, Clay joins Stephen Douglas in crafting a bi-partisan bill they hope will gain Congressional passage.

Two sticking points surface immediately. The first lies in deciding how much time should pass before a new Territory can apply for admission; the second, whether or not slaves will be permitted to arrive in advance of the application.

The South is very clear about its wishes on both counts.

It favors a long period of “Territorial” status, and one where slave owners are able to enter and settle down, well before a “pop sov” vote is taken. The Southern assumption being that “dislodging” slavery once it exists would be much more difficult than banning it in the first place.

February 5, 1850

The “1850 Omnibus Bill” Is Presented To Congress

Working together the two powerful senators arrive at what becomes the “Omnibus Bill,” promising the South that the future of slavery in the New Mexico and Utah Territories would be decided by “popular sovereignty” voting, and not by any blanket ban such as the Wilmot Proviso.

It also allows for settlers to immediately bring slaves into the Mexican Cession lands while remaining intentionally vague as to the elapsed time between Territorial status and admission to statehood.

To further sweeten the pot for the South, it delivers on three more wishes that emerge in the early negotiations:

- Granting the slave state of Texas $10 million to settle its boundary disputes with New Mexico.

- Explicitly recognizing that slave ownership (albeit not trading) will continue in DC.

- Announcing a new Fugitive Slave Law that will allow southern bounty hunters to enter northern states and forcibly remove all proven run-away slaves.

On February 5, 1850, Clay introduces his Omnibus Bill in the Senate.

What follows is a Congressional debate on slavery that rivals the 1820 Missouri Compromise in both importance and in soaring rhetoric.

It also marks the final curtain for the three long-term “giants” of the Senate – Calhoun, Webster and Clay – and the emergence of the new men who will dominate the floor for the next decade – Jeff Davis, Robert Toombs, Stephen Douglas, Henry Seward, and Charles Sumner.