Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 215: Buchanan Moves To “Clean Up Utah”

March 1857

Political Pressure Mounts On Buchanan Around Utah

With the Dred Scott victory in hand and Robert Walker headed off to resolve Bloody Kansas, Buchanan turns his attention to another domestic problem that has gained public visibility during the 1856 election campaign.

Stated simply, it involves finding a solution to what is broadly seen as renegade behavior among members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and their leader, Brigham Young.

For a full decade the Mormons have been settled in the Utah Territory, developing their community and practicing their religious beliefs.

But this becomes awkward for Buchanan and Washington on two dimensions. First because the Mormons seem to operate almost as a separate nation, independent of federal controls; and second because rumors persist that they are continuing their historical practice of polygamy on territorial land.

While there is no law against polygamy until 1862, it is almost universally condemned by American public as a violation of biblical scripture.

The topic also surfaces during the national presidential campaign of 1856 when Buchanan’s Republican opponents pass a platform plank calling for ridding Utah of “the twin relics of barbarism, slavery, and polygamy.”

1823 Forward

The Mormons Have Faced Decades Of Local Resistance Over Their Polygamy

Followers of the Church have suffered through a long history of public antagonism by the time they finally reach their “New Jerusalem” home in Salt Lake City in 1847.

Some hostility traces to the fact that many of their beliefs fall outside of the standard Protestant traditions. Thus while affirming themselves as Christians, they supplement Biblical scripture with their own Book of Mormon and other sacred texts, and reject many New Testament creeds and liturgy. But by far the most intense criticism they encounter relates to the practice of what they call “plural marriages” or “spiritual wifery,” and what Americans in general see as “blasphemous polygamy.”

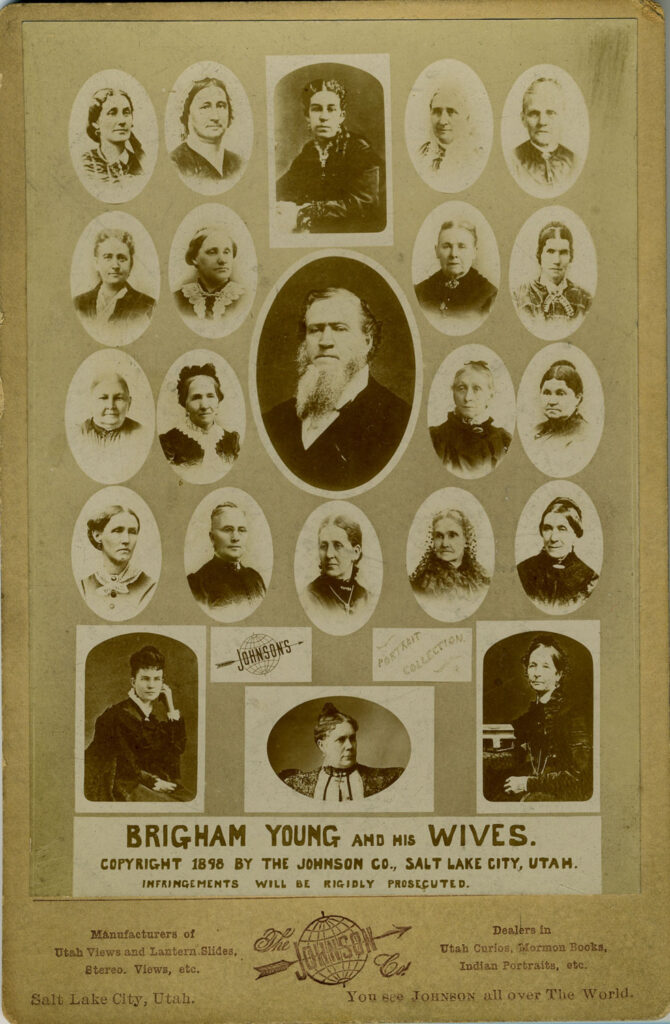

According to church elders, polygamy facilitates the propagation of the faith, insures all women of the protections that accompany marriage, and fosters a sense of cohesion among the membership. It is not mandatory, but both of the Mormons most famous spiritual leaders – Joseph Smith, who founds the church in 1823 in upstate New York, and his successor, Brigham Young – have upwards of thirty wives during their lifetimes.

Despite various attempts to conceal the practice, word invariably leaks out, prompting immediate condemnation of all Mormons by local communities, and attempts to force them to move elsewhere.

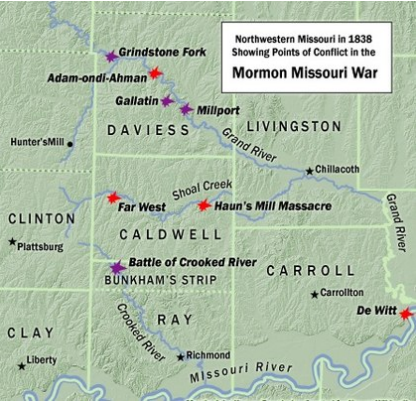

Their first displacement comes after they abandon their home in Kirtland, Ohio and move west in response to Smith’s prediction of the Second Coming of Christ. This 800 mile trek takes them 1831 to Jackson County, Missouri, where they settle in for two years before local mobs, learning of polygamy, drive them from their homes. In response, Smith negotiates with the Missouri state legislature, which cedes him control over nearby Caldwell County on the condition that his followers remain within its borders. But that agreement breaks down when new Mormons enter Davies County and are attacked.

Violence begets violence, and on Independence Day 1838, Smith’s off and on second-in command, Sidney Rigdon, announces that the Mormons will give no quarter if resistance continues.

That mob that comes on us to disturb us, it shall be between us and them a war of extermination; for we will follow them until the last drop of their blood is spilled; or else they will have to exterminate us, for we will carry the seat of war to their own houses and their own families, and one party or the other shall be utterly destroyed.

This call to action sparks the First Mormon War in Missouri, with a series of battles and raids that mirror the events in Kansas for their savagery. After ten weeks and roughly twenty-five murders, the state militia steps in to capture and jail both Smith and Rigdon on November 1, 1838 at the town of Far West. Their release follows quickly, after they promise to abandon Missouri and move to Illinois.

To accomplish this move, the Mormons literally buy the town of Commerce, Illinois, and rename it Nauvoo, a Hebrew word for “beautiful place.” Between 1839 and 1844 they proceed to turn Nauvoo into a boom town, albeit one that favors church members and leads to resentment among the non-Mormon community. Open hostility flares after a break-away Mormon group, intent on ending Joseph Smith’s control of the church, publishes an expose about his multiple wives – what they label “whoredom in disguise” — in the Nauvoo Expositor.

When Smith’s backers destroy the paper’s printing press, the nearby towns of Warsaw and Carthage Illinois both mount attacks against the Mormons. The Warsaw Signal declares:

We hold ourselves at all times in readyness to co-operate with our fellow citizens . . . to exterminate, utterly exterminate, the wicked and abominable Mormon leaders…Strike them! For the time has fully come.

Arrest warrants are issued for Smith and his brother Hyrum, and they agree to go to jail in Carthage after Illinois Governor Tom Ford guarantees their safety. But the protection proves inadequate as a mob some one hundred strong crashes the jail on June 27, 1844 and murders both men after a firefight. Joseph Smith is thirty-eight and Hyrum is forty-four when they are killed. Charges are subsequently brought against five assailants, but all are acquitted for lack of evidence that they fired the fatal shots.

With Smith gone, a succession debate finds two of his closest associates, Sidney Rigdon and Brigham Young, at odds. The result is the creation of a ruling Quorum of Twelve Apostles, with Young as president.

It is Young who concludes that the faith will thrive only if it escapes to a home of its own beyond the reach of the “gentiles.” In February 1846, the Mormons, some 20,000 strong, begin to leave Nauvoo and head west. Those left in the city are attacked by anti-Mormon bands into the Fall of the year, when the roughly 2,000 remaining stragglers finally surrender the town.

July 24, 1847 – March 1857

Brigham Young’s Theocratic Rule Over Utah Provokes Buchanan To Intervene

Young’s contingent crosses the frozen Mississippi and sets up winter camp at Council Bluffs, Iowa, before resuming west along the Oregon Trail in the spring of 1847. The lead group comprises 143 men, three women and two boys, traveling in 72 wagons — accompanied by some 93 horses, 66 oxen, 52 mules, 19 cows, 17 dogs and a batch of chickens. After a three month journey covering some 940 miles, they arrive on July 24, 1847 at the shores of the Great Salt Lake, with Young declaring this their final destination.

While the land he chooses is still officially owned by Mexico, it will be “ceded” on February 2, 1848 to the U.S. in the war-ending Treaty of Hidalgo, and renamed the federal Territory of Utah.

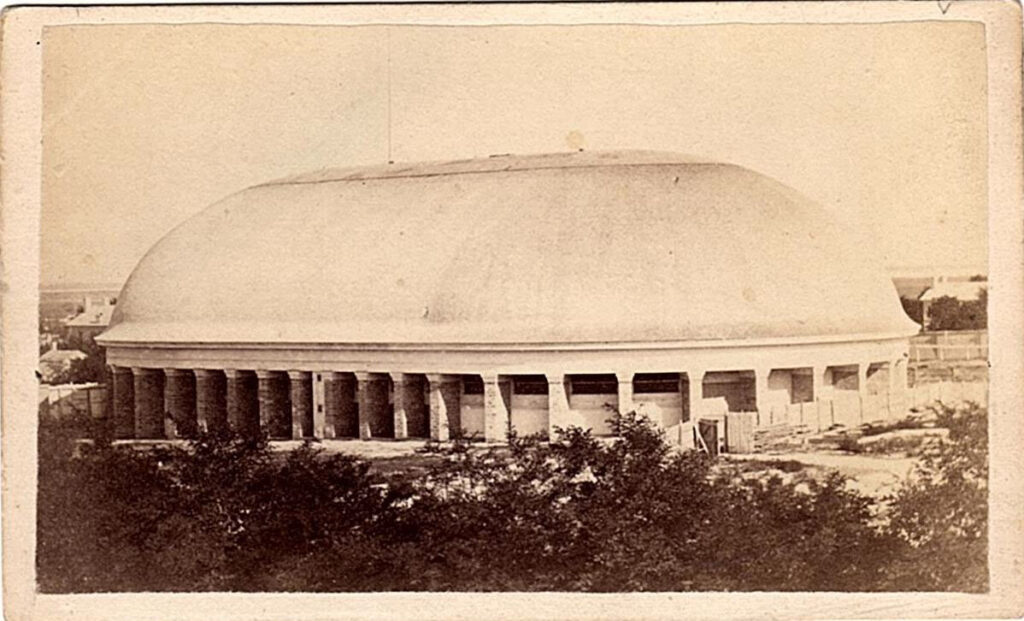

Just four days after settling, Young begins the task of creating his “New Jerusalem” by selecting a site for the Mormon Temple, a massive structure of over 250,000 square feet, which will take five years to build. From there he lays out his grand plan for the “State of Deseret,” a word meaning “honeybee” to the Mormons, and symbolizing their highly valued virtue of “industry.” Young is confident that the industry of his followers will transform his isolated land into the dominion he envisions, if only they are left alone to thrive. As he says:

If the people of the United States will let us alone for ten years…we will ask no odds of them.

Here again Young distinguishes the Mormons from the “people of the United States,” and in so doing signals his intent to govern Deseret as a “theocracy” dominated by religious, not civil, dictates.

As in Missouri and Illinois, the Mormon community quickly blossoms. The population grows to 35,000, supported by infrastructure that includes farms, schools, roads, storefronts, industry, and importantly, access to fresh water since the Great Salt Lake is undrinkable.

The federal government is also cooperative early on. Young’s recruitment of a 500 man “Mormon Brigade” to support the Mexican War wins approval from Washington, and he tries in 1848-49 to have the State of Deseret admitted to the Union. Congress rejects this plea, given the lack of survey data and border boundaries for the territory, which initially sprawls across nine eventual states. However, the 1850 Compromise finally clarifies the geography and on February 3, 1851, President Millard The Fillmore names Brigham Young the first official Governor of the Utah Territory. This marks the high watermark in relations between Washington and the Mormons.

Subsequent strains materialize from three factors. The first is the already familiar resistance to polygamy, which intensifies after an August 29, 1852 speech by Orson Pratt, a Quorum of Twelve members, publicly acknowledging the practice of “plural marriage” within the state. This is followed later on by more negative publicity in the form of an expose titled The Horrors of Mormonism written by F.G.T. Margetson, an angry religious turncoat.

A second source of tension is the “Act in Relation to Service” legislation passed by the Mormons on February 4, 1852. It legalizes slavery and extends it beyond blacks to local tribespeople. Young aggressively encourages the practice based on the same logic offered by the South – namely that it would support inculcating the virtues of leading a “useful life” and open a path to religious faith and salvation.

It is, however, a third rift – Young’s determination to govern Utah as a theocracy – that finally forces the federal government back into the affairs of the Mormons.

Throughout Franklin Pierce’s term, Young rules his state with an iron hand, his intent being to insure that the population and industry are dominated by Mormons, and that civil affairs are conducted in line with religious guidelines. This leads on to clashes with various federal officials, such as land surveyors, whom he tries to bar, and judges, whose decisions he is wont to overrule. Two judges in particular – George Stiles and W. W. Drummond – become outspoken critics of Young after returning to Washington.

Once in the White House in March 1857, the new President publicly vows to “clean up” the territory.

May 28 – August 2, 1857

A New Governor Heads Toward Salt Lake City

The President’s first move against the Mormons occurs on May 28, 1857 when he order Secretary of War, John Floyd, and General Winfield Scott to form the Military Department of Utah, headquartered at Ft. Leavenworth. This is intended to provide any future troops that might be needed in the territory.

He follows this on June 29, by announcing that Utah is in a state of rebellion, and on July 13, by naming a new Governor to replace Young — Alfred Cummings, a non-Mormon ex-mayor of Augusta, Georgia, currently serving as an Indian Affairs agent.

Five days later, Cummings sets out for Salt Lake City to assume his new duties, accompanied by a small military contingent led by Captain Stuart Van Vliet.

What’s missing, however, are the additional 1,500 U.S. troops assigned by Buchanan to force Young to step aside in favor of the new governor. The delay here traces to Secretary of War, John Floyd, who officially assigns Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston to lead the company, only for find that he is occupied with other duties in Kansas.

By the time Johnston joins his command and begins marching west, it’s clear that the winter weather will require him into an extended encampment before reaching Salt Lake.

When the cagey Young learns of Johnston’s delay, he decides to signal his intent to resist any U.S. invasion.

On August 2, 1857, he talks openly about a Mormon secession, then calls up of the “Nauvoo Legion” militia and destroys Ft. Bridger, a venerable outpost 100 miles northeast of the capital.

This establishes the pattern of brash but limited bluffs by Young aimed at keeping control of the Utah Territory in Mormon hands.