Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 30: British Acts Of War Lead to The Ruinous “Embargo Act”

1805-1806

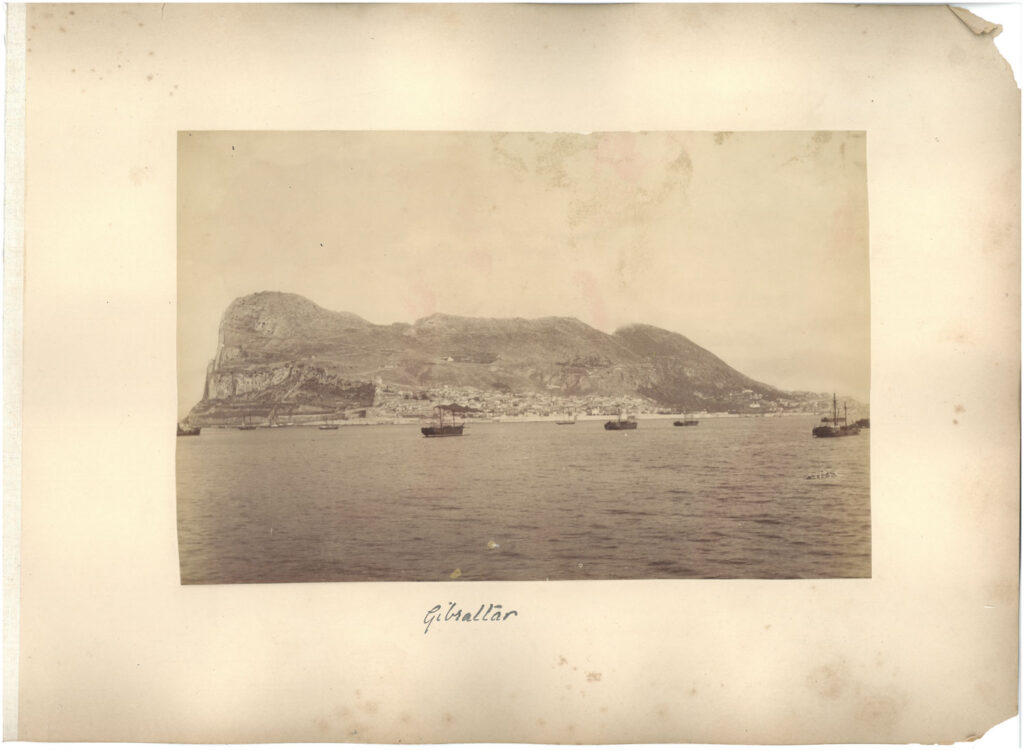

Britain “Impresses” US Sailors To Fight France

Napoleon’s rampage across Europe and his war with Britain inevitably brings Jefferson into the middle of a conflict he would rather avoid.

The conflict is triggered by British “impressment” of American sailors.

Unlike the French with its dominant land army, the British rely on their Royal Navy to defend the homeland and their possessions around the globe. By 1805, as Napoleon notches one victory after another, they rush to build up their corps of able-bodied seamen from a peacetime force of 10,000 to the 140,000 level they feel are needed for war. Their search turns in part to British sailors who have deserted the harsh conditions and disciplines imposed by their ship captains. Nelson pegs this figure at around 40,000 men – with many of them taking refuge on board more lenient American ships.

Britain’s plan is to “retrieve” these nationals and return them to the Royal Navy. At the same time, King George III, still smarting from the French-backed defeat at Yorktown, and assuming that Jefferson favors his former allies, supports the notion of snatching American sailors as a justifiable form of pay-back.

Before proceeding, however, Britain looks for a legal rationale to stop and board American ships. Here they cite their own high court decision, rendered on May 22, 1805, against the American merchant ship Essex, accused of violating The Rule of 1756 by transporting cargo banned during times of war.

In turn, they now use The Rule of 1756 as a legal excuse for stopping US ship to examine their cargo – and, at the same time, to seize American sailors.

“Press gangs” are formed to carry out this new policy, and by 1806 it’s estimated that some 10,000 seamen have been taken, some British deserters, but also many American citizens. A major diplomatic controversy follows.

On February 12, 1806, the Senate passes a resolution condemning Britain’s seizure of American ships and seamen. Actual sanctions follow on April 18 in the Non-Importation Act which bans all British hemp, brass, nails, wool, glass, clothing, leather, hats and beer from entering American ports.

Further commercial interruptions follow. Napoleon adds to the controversy on November 11, 1806, with his Berlin Decree which intends to cut Britain off from all foreign imports, including those from the United States. When the British follow suit, all shipping activities between America and the two combatants are curtailed.

Jefferson continually tries to defuse the tensions with Britain. In August 1806, Secretary of State, James Monroe, and his aid, William Pinkney, open talks with representatives of the Whig Prime Minister, Lord Grenville. These lead nowhere, and end with a December 31 Treaty that disappoints Jefferson to the extent that he refuses to send it to the Senate for approval.

June 22, 1807

HMS Leopold Attacks US Ship Off Norfolk, Virginia

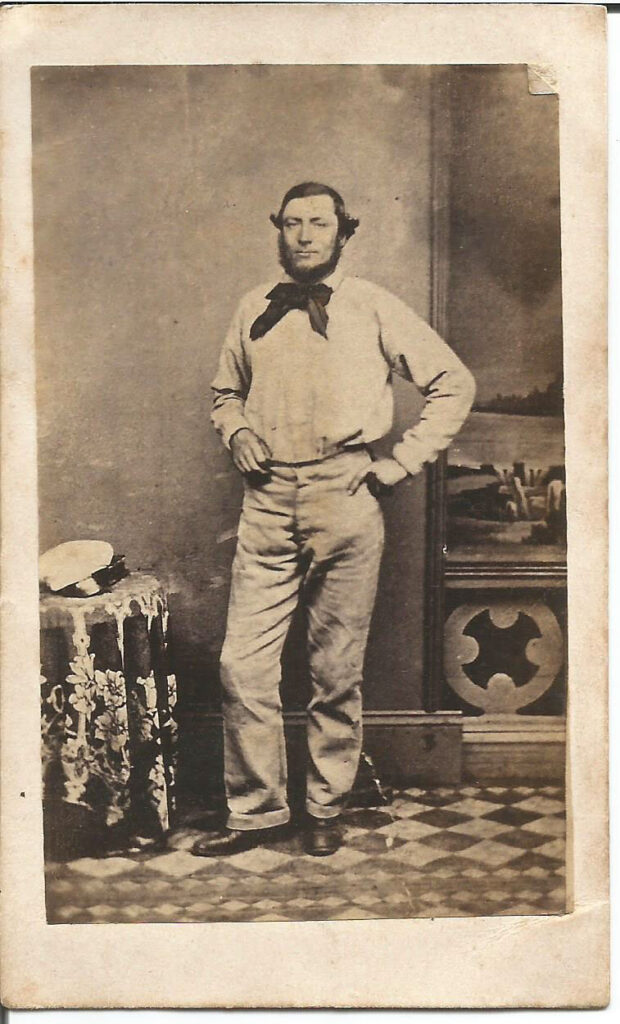

Six months later, on June 22, 1807, the conflict ratchets up sharply as the 50 gun HMS Leopard attacks an American naval ship, the USS Chesapeake, off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia. After falsely informing the Leopard that it has no British deserters in its 340 man crew and that it will not submit to a boarding party search, the Chesapeake turns to sail away. As it does so, it is struck by a full broadside bombardment. The surprised Americans are able to get off only one round of return fire before they strike their colors and surrender. Three U.S. sailors are killed and another 18 are wounded in the brief action.

A press gang from the Leopard boards and searches the Chesapeake and arrests four men claimed to be British nationals and deserters. Three turn out to be Americans, eventually released after their sentence of 500 lashes is commuted. The fourth man, Jenkin Ratford, is in fact a British born deserter. He is soon tried and hanged from the yardarm of the HMS Halifax.

The American public is outraged by the incident, and Jefferson feels the pressure to retaliate.

Never since the Battle of Lexington have I seen this country in such a state of exasperation as at present, and even that did not produce such unanimity.

His response, however, is measured and restrained. Secretary of State James Madison issues a protest which demands that the British government condemn the Leopard’s actions, return the captured Americans, remove its warships from American waters and end the practice of impressment.

On October 17, Britain responds publicly, declaring its intent to ignore the American demands and step up its impressment activities.

Jefferson is now caught between the open belligerence of the British and the growing public demand for further action to defend the nation’s honor.

He refuses to call Congress into a special session for fear of an immediate war resolution, but he does order all U.S. warships abroad to head home in case they are needed.

He then ponders what to do about America’s fleet of merchant ships.

December 22, 1807

The Embargo Act Of 1807 Boomerangs On The Administration

Secretary of State James Madison proposes a solution: the safest way to avoid war and to protect the nation’s ships lies in restricting all commercial traffic between America and all foreign ports.

Ships that stay in American waters and move only between one domestic port and another cannot be accused of interfering in the European conflict, and will be more readily protected by the U.S. naval fleet.

Jefferson announces this idea in his seventh annual message to Congress on December 18, 1807.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States: The communications now made, showing the great and increasing dangers with which our vessels, our seamen, and merchandise are threatened on the high seas and elsewhere, from the belligerent powers of Europe, and it being of great importance to keep in safety these essential resources, I deem it my duty to recommend the subject to the consideration of Congress, who will doubtless perceive all the advantages which may be expected from an inhibition of the departure of our vessels from the ports of the United States. Their wisdom will also see the necessity of making every preparation for whatever events may grow out of the present crisis.

The Embargo Act of 1807 passes in the Senate on December 18 by a margin of 22-6. Of the six nays, three are Federalists (Pickering of Mass, Hilhouse of Md and White of Del) and three are Democratic-Republicans (Crawford of Ga, Maclay of Pa and Goodrich of Conn). The House follows suit by an 82-44 margin, and the bill becomes law on December 22.

Details of the 1807 Act are as follows:

- American merchant ships are banned from setting sail to any and all foreign ports

- Ships engaged in domestic traffic must post a “good will” bond before departing

- U.S. Navy warships will enforce these rules.

- Any exceptions must be authorized directly by the President.

If effect, Jefferson and Madison intend to pull America back into a defensive posture, while Britain and France fight it out for European hegemony.

But instead of the public support they expect for the Act, the result is open hostility.

States that depend on international trade experience sharp economic downturns. Traders turn to smuggling to earn a living. Prices jump up on “necessities of life” in short supply and down on embargoed exports. Fear spreads that, if the ban goes on long enough, European customers for American exports will find alternative sources of supply.

On February 1, 1808, ex-Secretary of State Thomas Pickering calls for a convention of states who wish to “nullify” the act. Connecticut Governor John Trumbull follows on February 22 by telling his legislature that the act is unconstitutional, and that he will refuse to have the state militia enforce it.

Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin also shares his concerns with Jefferson.

As to the hope that it may…induce England to treat us better, I think is entirely groundless…government prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated; and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves.

But neither Jefferson nor Madison is ready to back off in the face of the internal pressure. Rather than reversing course, they embark on an almost Adams-like crackdown on those who resist the ban.

The most egregious violations appear in the Northeast, with overland and river route smuggling to and from Canada becoming commonplace. To suppress this, Jefferson invokes the Insurrection Act of March 3, 1807 — which gives him the power to call in the standing federal army, not simply state militias, to suppress those obstructing the law.

[I]n all cases of insurrection, or obstruction to the laws, either of the United States, or of any individual state or territory, where it is lawful for the President of the United States to call forth the militia for the purpose of suppressing such insurrection, or of causing the laws to be duly executed, it shall be lawful for him to employ, for the same purposes, such part of the land or naval force of the United States, as shall be judged necessary, having first observed all the pre-requisites of the law in that respect.

March 1, 1809

The Act Is Repealed As Jefferson’s Second Term Ends

On March 12, 1808, further strictures are added to the Embargo Act. Stiff $10,000 fines for those violating the ban become law, and port authorities are granted the power to search suspect ships and seize cargoes, without securing advance warrants. Madison remains convinced that the Embargo will succeed if only it is properly enforced.

Even Jefferson’s most devoted backers are surprised by his readiness to use central government weapons – even the standing army — against the clear wishes of a host of individual states and citizens. Hamilton might resort to this tactic; but to watch Jefferson and Madison engage this way is shocking to many Democratic Republicans.

In the end, the 1807 Embargo survives over 15 months before the President gives in. The Act has had little effect on the European war, while producing widespread public resistance at home, including a resurgence of the Federalist party. Its only benefit has been to encourage the growth of domestic manufacturers, to fill the void in foreign imports.

Despite opposition from Madison, Jefferson repeals the Embargo during his last week in office.

On March 1, 1809, the so-called Non-Intercourse Act goes into effect. It allows shipping to resume with all nations except Britain and France. It also dangles a carrot in front of the two belligerents, offering a resumption of trade in exchange for a commitment to end future interference with American ships and sailors.

As with many presidents, the toll taken by second-term reversals weighs heavily on Jefferson. His last six months in office reflect near paralysis, and, as typical, he captures his feelings in a succinct metaphor:

Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.

Of course neither his short-term influence on the future course of American politics, not his long-term legacy, ends in 1809 as he departs for Monticello.

Sidebar: Thomas Jefferson’s Lasting Legacies

Jefferson’s Principles Of Government

Thomas Jefferson’s political philosophy will dominate the American scene over the next four decades.

The Democratic Party he founds turns the country away from the Federalist principles espoused by Washington, Hamilton and Adams and relegates their followers to minority status in congress.

Jefferson also works the political process in such a way that he hands the presidency over to his two Virginian protégés – Madison and Monroe – thereby extending his behind-the scenes’ power another 16 years, almost to his death (and Adams) on July 4, 1826, fifty years to the day from the adoption of his monumental Declaration of Independence.

The central themes of Jefferson’s presidency will ring down the generations to follow:

- The shift in focus from the original 13 colonies to the acquisition and development of the vast lands west of the Appalachians and then of the Mississippi River – a shift which sets America’s “manifest destiny” in motion and provides the Democratic Party with a long-run lock on western voters.

- Commitment to firmly integrating the new states into the Union based on the ideals in the Constitution.

- The libertarian drive to insure that power remains in the hands of individual citizens distributed across the states – and away from centralized power blocks, be they in the form of government or churches or economic entities.

- A wish to sharply limit the size of a central government and concentrate its role on foreign policy rather than domestic policy which, according to “his” Tenth Amendment, involves “rights belonging to the states.”

- Belief that common local men will prove superior to distant politicians in debating and resolving social needs or problems arising in their own communities.

- Abhorrence of public debt and strict limits on taxation and spending, in order to minimize government’s impact on the lives of citizens.

- A deep and abiding distrust of bankers, soft money and the banking system in general, especially Hamilton’s central Bank of the United States.

- A similar fear of capitalism and corporations, where money trumps labor and white men run the risk of being reduced to wage slaves.

- A conviction that all white Americans should have access to free public education, and to the development of outstanding colleges, such as the University of Virginia, which he founded in 1785.

- Undying faith in the power of the Union and a commitment to preserve it against all threats, foreign or domestic.

While also having faith in the basically good intentions of common men, he firmly believes that leadership belongs with a “natural aristocracy.” As he says in an 1813 note to Adams:

For I agree with you that there a natural aristocracy among men. The grounds of this are virtue and talents. There is an artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents. The natural aristocracy I consider the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.

Interwoven with all these principles is Jefferson’s commitment to the southern, agrarian way of life he has known since childhood – including slavery.

So a final part of his legacy comes back to an examination of his words and deeds relative to that institution.

Jefferson’s Rationalizations On Slavery

Thomas Jefferson lives among slaves all his life. They provide the hard labor required to build his mountain-top home and miniature town, grow and harvest his farm crops, operate his mill and brewery, his spindles and nailery, cook and serve his fine French cuisine, pay off his debts, and, in the case of Sally Hemmings, act as his surrogate wife after Martha dies in 1782.

They seem to fascinate him intellectually. He studies them: their physical, mental and emotional traits, their joys and sorrows, the ways in which they deal with their fate. Almost in a scientific fashion, he records these observations in his Farm Book and in his Notes On The State of Virginia, first drafted in 1781 and completed in 1785.

Throughout his life he also reflects on the institution of slavery, and on his personal relationship to it.

In a telling 1805 note to William Burwell, his private secretary, he describes a range of attitudes toward slavery he has encountered among owners:

There are many virtuous men who would make any sacrifices to effect it. Many equally virtuous who persuade themselves either that the thing is not wrong, or that it cannot be remedied. And very many, with whom interest is morality.

Over time, he seems to see himself belonging in the first class – ready to make “any sacrifices” to end the practice. This is clear in a 1788 letter to Jacques Brissot, a leading proponent of abolition in France.

You know that nobody wishes more ardently to see an abolition not only of the trade but of the condition of slavery: and certainly nobody will be more willing to encounter every sacrifice for that object.

He reiterates this, using similar words, a quarter of a century later in an 1814 letter to his friend, the academician, Thomas Cooper.

There is nothing I would not sacrifice to a practicable plan of abolishing every vestige of this moral and political depravity.

Like Hamlet, Jefferson asserts that he is ready to act to correct that which is morally wrong to him — if only he can arrive at a proper remedy. And therein lies the rub.

His contact with the Africans has convinced him that they probably have descended from a different species, and are biologically inferior to white men. Given this, he tells Edward Bancroft in 1789 that releasing the slaves would be tantamount to “abandoning children.”

As far as I can judge from the experiments which have been made, to give liberty to, or rather, to abandon persons whose habits have been formed in slavery is like abandoning children.

Other barriers to abolition materialize over time.

If freed, the Africans could never be assimilated. His 1785 Notes lay out the reasons why.

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.

In 1803 a letter to James Monroe cites the events surrounding Toussaint’s slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) as evidence of the inevitable violence between the two races, if freedom is granted.

I become daily more & more convinced that all the West India islands will remain in the hands of the people of colour, & a total expulsion of the whites sooner or later take place.

What is left then is re-colonization, the solution he references in his 1814 letter to his Virginia neighbor and anti-slavery advocate, Edward Coles.

I have seen no proposition so expedient on the whole, as that of emancipation of those born after a given day, and of their education and expatriation at a proper age.

So Jefferson appears to come full circle, back to his 1785 Notes. His intellect tells him that no matter the biological inferiority of the Africans, taking away their freedom and forcing them into slavery is morally corrupt and an affront to God’s justice.

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it…The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst passions, and thus nursed, educated and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities.

If a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is to be born to live and labor for another … or entail his own miserable condition on the endless generations proceeding from him.

Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever.

He “trembles” again for his country during the 1820 Missouri crisis – “a fire bell in the night” – and once more, as seer, in an 1821 autobiographical reflection.

Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free. Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government.

Taken together, Jefferson’s rhetoric is of the virtuous man who recognizes the evils of slavery, is ready to make any sacrifice to end it, but simply sees no viable way out of the dilemma.

All that’s left for him is to do the best he can in the inevitable presence of slavery — a Herculean task, as he points out in his Notes:

The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.

One suspects again that Jefferson sees himself in this observation – the rare “prodigy” able to rise above the coarsening realities of slavery that surround him.

But is this truly the case? How well do Jefferson’s words match up with his actions as a slave owner?

The record here seems mixed. There is no evidence to support the notion that he was personally harsh in dealing with his slaves. He did, however, expect reasonable levels of “industry” from them, and hired overseers such as William Page and Gabriel Lilly, both known for resorting to the whip to enforce discipline.

More troubling is his assignment of young children to handle some particularly onerous tasks. Because of their short stature, some spend days at a time on hands and knees in the dirt plucking and killing tobacco worms. Others end up in the “nailery,” crowded around a flaming forge in the summer heat, converting iron nail rods into various sizes of finished nails. Jefferson is particularly proud of this factory operation, oversees it himself, and remarks on its profitability.

I now employ a dozen little boys from 10. to 16. years of age, overlooking all the details of their business myself and drawing from it a profit.

It is precisely this tendency to prioritize personal profits over the well-being of his slaves that counts most in calling Jefferson’s moral sense into question.

On one hand he will insist that the slaves are part of “his family;” on the other, he will sell them off whenever economic necessity calls. For a man with great sensitivity to language, his words about “breeding women” in his Farm Book are both cold and calculating.

The loss of 5 little ones in 4 years induces me to fear that the overseers do not permit the women to devote as much time as is necessary to the care of their children; that they view their labor as the 1st object and the raising their child but as secondary.

I consider the labor of a breeding woman as no object, and a child raised every 2. years is of more profit then the crop of the best laboring man. In this, as in all other cases, providence has made our duties and our interests coincide perfectly…. With respect therefore to our women & their children

I must pray you to inculcate upon the overseers that it is not their labor, but their increase which is the first consideration with us.”

Likewise his “investment advice” to friends.

Invest every (spare) farthing in land and negroes, which besides a present support bring a silent profit of from 5 to 10 per cent in this country, by the increase in their value.

Here indeed his slaves are reduced from “family” to “property,” to be bred and fed and sold at auction. And sell them he does. Never as a “commercial trader” like his father-in-law; rather out of expediency, to buy the many things he wants for Monticello and to pay off debts. In the decade from 1784 to 1794, records show that he disposes of some 161 slaves. More sales would follow, always accompanied by a stated wish to “keep families together”…

To indulge connections seriously formed by those people, where it can be done reasonably.

Always accompanied by…

Scruples about selling negroes but for delinquency, or on their own request.

Reservations aside, the commitment to “silent profit” also extends to Jefferson’s last will and testament. Unlike Washington, he refuses to free his slaves upon his death, with the exception of some eight members of the Heming’s family.

Words and deeds. Weighed in the balance, the record is mixed.

Jefferson is by no means the callous or uncaring slave master; but neither is he the “prodigy” he refers to in his 1805 note to Burwell.

At moments of economic necessity, self-interest too often trumps morality.