Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 164: Boston Remains The Hotbed Of Resistance To The Fugitive Slave Act

February 15, 1851

Runaway Shadrach Minkins Is Rescued From A Courtroom In Boston

In February 1851, the national spotlight on the Fugitive Slave Act shines again on the city of Boston, only two months after coverage of the daring escape of Ellen and William Craft.

This time the case involves a runaway named Frederick “Shadrach” Minkins – and results in an act of violence carried out in a federal courthouse by a band of mostly black protesters.

Minkins escapes from Norfolk, Virginia, on May 5, 1850 and arrives, probably by boat, in Boston, where he plans to begin his new life as a free man. He joins the Twelfth Baptist Church and finds a job as a waiter at Taft’s Coffee House on Cornhill Street.

But his Norfolk owner, John DeBree, soon hires a slave-hunter, John Capehart, and sends him north, with legal documents in hand, to retrieve his “property.” Capehart tracks Minkins to Boston and petitions Judge George Curtis to issue an arrest warrant. Given his awareness of the local Vigilance Committee’s history of trying to disrupt “captures,” Capehart plans to take Minkins unawares as he is working at the coffee house.

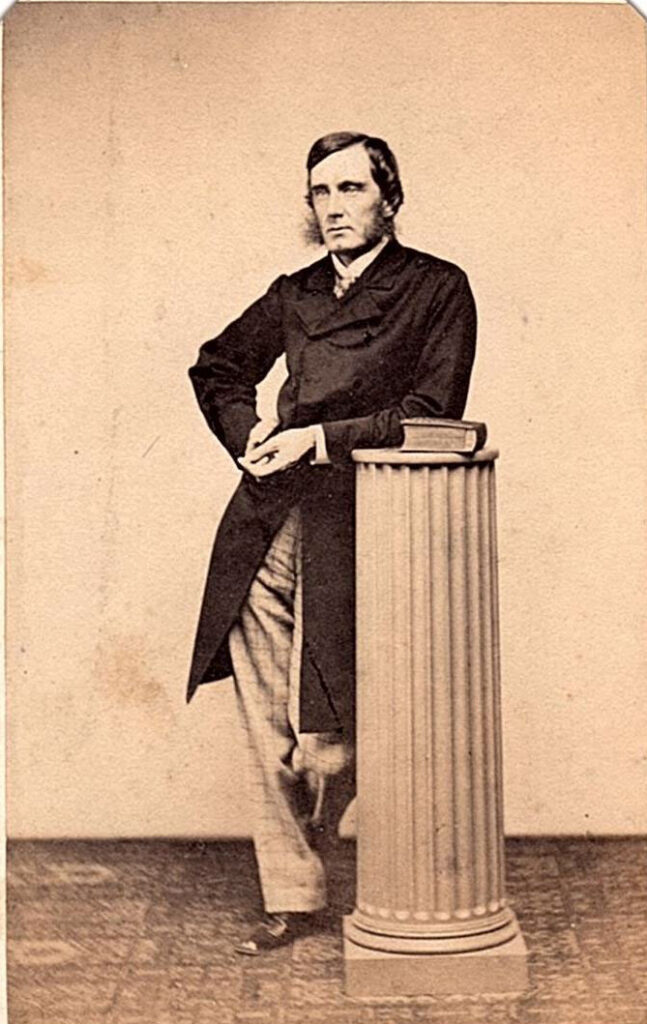

While U.S. Marshall Patrick Riley carries out the arrest, it involves enough of a raucous that Committee members, protesters, and lawyers show up at the nearby courthouse soon after Minkins arrives in custody. This “defense team” is led by the runaway, Lewis Hayden, now a wealthy merchant who attends “Shadrach’s” church and is a well-known black abolitionist. He is joined at the courthouse by several prominent lawyers, including Robert Morris, the first black admitted to the Massachusetts bar, and Richard Henry Dana, a white Harvard graduate, famous for his Mayflower lineage, his legal practice, and an 1840 sea novel, Two Years Before The Mast.

While Capehart hopes to conduct an immediate trial, Minkins’ lawyers convince Judge Curtis that they need time to prepare a proper defense. He grants them a three-day stay and remands Shadrach to custody.

However, before the prisoner can be taken to jail, a crowd of perhaps two hundred, largely freedmen, burst into the courtroom, overpower the deputies, and haul Shadrach off to safety.

He is hidden for several hours in the attic of a nearby home, before Lewis Hayden escorts him personally to an Underground Railroad site in Concord. From there, Minkins moves along the tracks, ending up in Montreal, where he will spend the remaining twenty-five years of his life.

1851

Seven Shadrach Conspirators Are Tried But Acquitted

The abolitionists in Boston gloat over Minkins rescue. Reverend Theodore Parker calls it the “most noble deed done in Boston since the destruction of the tea.” Lloyd Garrison overlooks the violence involved to declare, “nobody injured, simply a chattel transformed into a man by unarmed friends of equal liberty.”

The response in Washington is very different.

Both President Fillmore and Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, are appalled by the action of the Boston Vigilance Committee, which they regard as an outright flaunting of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Fillmore cites “dangerous combinations” ready to break the law, while Webster calls it “strictly speaking a case of treason.” Senator Henry Clay demands harsh penalties for all blacks and whites involved.

Meanwhile, the alarm across the South rings even louder – where the storming of the Boston courthouse is portrayed as akin to prior uprisings by blacks aimed at killing whites and ending slavery.

Fillmore responds with a “proclamation:”

I do further command that the district attorney of the United States and all other persons concerned in the administration or execution of the laws of the United States cause the foregoing offenders and all such as aided, abetted, or assisted them or shall be found to have harbored or concealed such fugitive contrary to law to be immediately arrested and proceeded with according to law.

This is followed by the arrest of nine men, all accused of helping Minkins escape.

Included here are Lewis Hayden, who clearly orchestrated the outcome, and Elizur Wright, a white editor of the local Commonwealth newspaper and a confirmed Garrison supporter, whose coverage of the affair openly applauds the rescue.

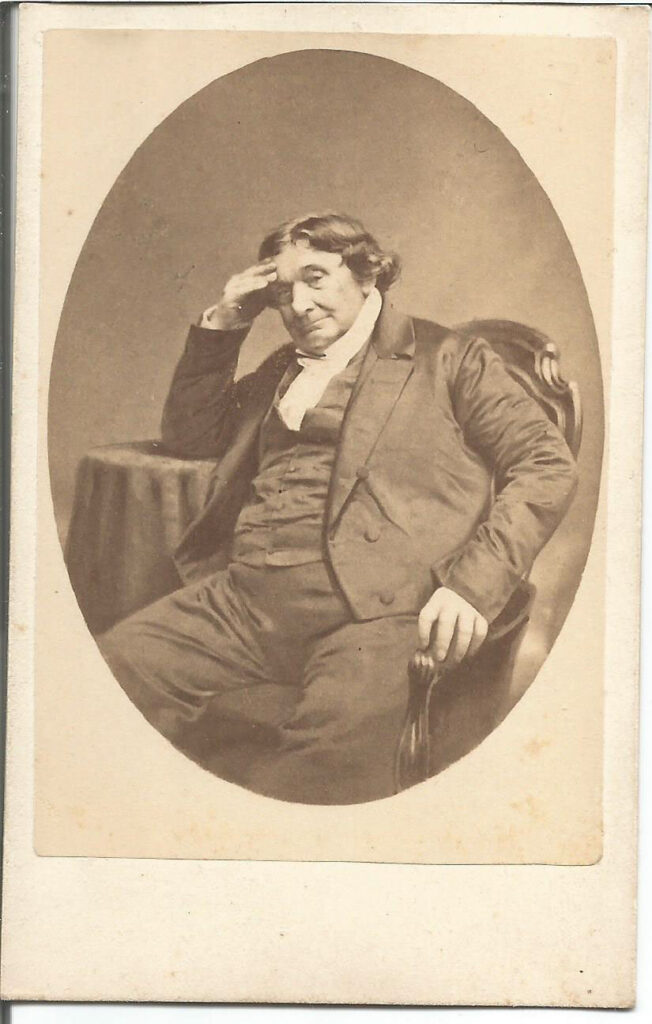

Eventually seven of the nine are tried in court, with their defense led by Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire, a noted abolitionist in his own right. Despite the evidence against them, all seven are acquitted in what opponents characterize as “jury nullification” – with emotional support for the defendants overriding the facts against them.

The acquittals represent another slap in the face to President Fillmore and his Southern supporters who enacted the Fugitive Slave Act – and stiffens their resolve to avoid any future repetitions.

They will not have long to wait to exhibit their will.

April 1851

Runaway Thomas Sims Is Captured In Boston

The national publicity and federal pressure surrounding the escape of Shadrach Minkins results in a tightened commitment to law and order among public officials in Boston. In turn, the Vigilance Committee mounts posters throughout the city warning all blacks of the increased threats they face.

CAUTION: Colored People of Boston, one and all.

You are hereby respectfully cautioned and advised to avoid conversing with the Watchmen and Policemen of Boston who are now empowered to act by order of the Mayor as Kidnappers And Slave-Catchers.

The threat becomes reality on April 4, when a runaway named Thomas Sims is arrested by the police.

Sims is seventeen years old at the time, and has been in Boston for only about seven weeks when picked up. His prior years are spent on a large rice plantation in Georgia owned by his master, James Potter. During his time there he has been trained as a mason and bricklayer, skills which make him uniquely valuable. He has actually approached Potter about buying his freedom for the sizable price of $1800, which he believes he can raise. When this offer is turned aside, Sims decides to escape.

On February 22, he secretly boards a brig, the M&JC Gilmore, in Savannah, and talks openly with the captain and crew members, after it is on its way to Boston, telling them that he is a freedman. When he arrives there, he finds a job as a waiter and tries to blend into the life of the city.

But Potter has no intention of allowing the escape to stand, and he goes about his pursuit in systematic fashion. He informs Henry Jackson, a Superior Court judge in Georgia, of his loss, and receives an official order to pursue and capture Sims. He names two witnesses who can personally identify him, and designates one, John Bacon, to serve as his “agent” to lead the chase.

When Potter learns that Sims is in Boston, an appeal goes to Mayor John Bigelow to support his recapture. Bigelow had failed to send his policemen after Minkins, but in this case he buckles to the pressure.

Officers run Sims down on April 4, 1851, and take him to the same federal courthouse from which Minkins had been rescued by the protesters. Only this time, Bigelow orders a band of soldiers to surround the facility and fire on any potential anti-slavery protesters who might try to free Sims.

Abolitionists quickly come to Sim’s defense and organize protest rallies. Lloyd Garrison weighs in, aiming his barbs at Daniel Webster:

Webster has at last obtained from Boston a living sacrifice to appease the Slave God of the American Union.

Fred Douglass offers another option:

The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers…carried down South (to) cool the ardor of Southern gentlemen, and keep their rapacity in check.

But the outcome this time will be decided in court before George T. Curtis, the U.S. Circuit Court Commissioner, the same judge involved in the Minkins hearing.

April 1851

Sims Is Tried And Sent Back To Slavery In Georgia

The trial of Thomas Sims lasts for several days and involves extensive arguments and cross-examinations by the attorneys involved. In this instance, it is by no means the type of “kangaroo court” hypothesized by many critics of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Sims’s defense is led by two highly respected advocates, Charles Greeley Loring and Robert Rantoul, Jr., the latter currently serving as a U.S. congressman from Massachusetts.

The case against Sims is, however, air tight. All required warrants have been executed properly and witnesses attest to his time on the Potter plantation, to his escape, and even to his time aboard the ship from Savannah to Boston.

Against these odds, Loring and Rantoul decide to focus their defense around questioning the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act itself. Loring leads the charge here:

I am profoundly convinced that the law to be enforced is a most dangerous encroachment upon the letter and spirit of the Constitution and upon the fundamental principles of human freedom and social security.

Judge Curtis allows this to play out in some depth during the trial and the final arguments, and acknowledges the issues raised in his final decision.

This decision would require but a very short time to pronounce, if there had not been raised a question of law, which I must examine and pass upon. The learned counsel for the prisoner have argued with great ability the question of the constitutionality of the Act of Congress under which this warrant was issued, and have called upon me, as they had a right to do, to affirm or deny it.

But in the end he concludes that the plaintiff has prevailed and Sims must return to the Potter plantation.

I can entertain no doubt whatever that it is my duty to grant to the claimant the certificate which he demands, and I do accordingly grant it. I feel it to be a public duty, in closing this decision, to express here my deep obligations to the marshal of the United States and to the marshal of the city of Boston, and the various officers serving under them, for the efficiency and prudence with which they have discharged their respective duties connected, with or occasioned by this hearing.

The defense will subsequently appeal to Judge Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, arguing that the state law banning slavery should provide protection for Sims. While Shaw is himself a lifelong opponent of slavery, he knows that federal law trumps state law, and rejects the plea.

On April 11, 1851, after Curtis renders his decision, Thomas Sim is escorted from the courthouse surrounded by a contingent of 300 sabre-carrying policemen who march him to the wharf, where he is put on a ship and returned to Savannah. Once there, he is taken to the public square and given 39 lashes, then sold on the auction block by Potter to a master in New Orleans.

(Ironically this sale takes him twelve years later to Vicksburg, Mississippi, site of a major Union victory during the Civil War, on July 4, 1863. During the action, Sims escapes to the Union lines and, with a pass signed by U.S. Grant, he makes his way back to Boston as a freedman.)

The Sims affair ends the fugitive slave turmoil in Boston for two years, until the case of Anthony Burns in 1853.

Both sides in the matter claim victory, the local Vigilance Committees citing the Minkins case, and law enforcement authorities doing the same with Sims.

The two Boston incidents, however, have a sizable ripple effect on public sentiment across the North, even among the vast majority, not engaged in the anti-slavery movement.

For some, the mere act of uprooting men and women and thrusting them back into chains, violates the core value of fair play and builds sympathy for all blacks.

For others, it simply raises the blanket feeling of hostility toward the “Slave Power” in the South. After all, slavery is their problem and “deputizing” Northerners to help them solve it is out of bounds.