Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 101: Another Race Riot Breaks Out In Cincinnati

Five years have passed since the border town of Cincinnati was last torn apart by racial violence.

At that time white mobs pillaged black neighborhoods following the publication of inflammatory newspaper articles by the abolitionist, James Birney.

Why the so-called “Queen City of the West” fosters such racial animosity may be explained in a telling observation from the French historian, Alexis De Tocqueville, who visits America in 1831:

Race prejudice seems stronger in those states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists, and nowhere is it more intolerant than in those states where slavery was never known.

Ohio is one such state that has never known slavery since entering the Union in 1803.

By 1840, however, the 95% white population in Cincinnati is living alongside 2,240 free blacks, many of whom have earned enough money to purchase their freedom. They have built their own community in the “Bottoms” neighborhood around the Bethel AME and Union Baptist Churches, opened three schools run by The Coloured Education Society, and hold upwards of 90 skilled labor jobs, from barbering to mechanics.

Still, the majority of mainstream white citizens want nothing to do with the Africans.

Not only do they regard blacks as a lesser species – the traditional 3/5th of a full man in the Constitution — but also as a danger – to both their physical safety and their economic future. For Cincinnati lies directly across the Ohio River from the slave state of Kentucky, where its commercial transactions depend heavily on a willingness to oppose both talk of abolition and support for run-away slaves.

The presence of Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati further complicates the matter.

Lane opens in 1829 to train Presbyterian ministers in the west. In 1834 it is the site of fierce debates over slavery, which divides its President, Lyman Beecher, who favors gradual emancipation and colonization, from students led by Theodore Weld, a Finney disciple, who calls for freedom now and assimilation. While Weld’s faction transfers to Oberlin College, some 220 miles to the North, abolitionist fervor still lingers in Cincinnati.

One proponent, the lawyer Salmon P. Chase, arouses the ire of local merchants in May 1841 when he wins a court case on behalf of Mary Towns, a runaway slave from Kentucky. This prompts the pro-slavery Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper to initiate a campaign against “trouble makers” riling up the black population.

September 3-4, 1841

Free Blacks Fight Back Against Rampaging White Mobs

As summer rolls on, the city is hit by a prolonged heat wave and drought, which causes the river to fall, along with jobs on boats and wharves. Tensions increase daily and random fights break out.

It’s unclear exactly what sparks the riot, but it begins at a candy store on Fifth Street owned by an abolitionist named Cornelius Burnett. Along with his sons, Burnett has recently fought local police who were demanding that he turn over a run-away slave. The incident is not forgotten and a white mob begins their rampage by demolishing Burnett’s store before heading into a black enclave, “Bucktown.” Once there they begin to pillage black homes and businesses.

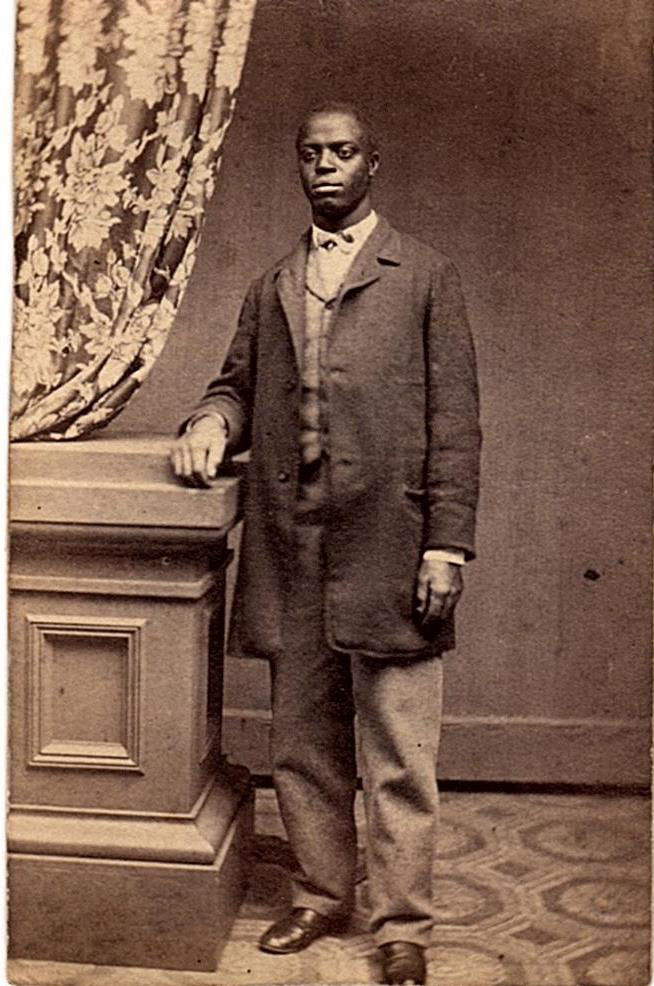

But rather than repeating their passive stance during the 1836 riots, blacks this time fight back, with some 50 organized and armed fighters led by 28 year old named Major James Wilkerson, grandson of a Revolutionary War soldier, and elder in the AME church.

After Wilkerson’s band initially drives them back on the night of September 3, white forces return with a six pound cannon and resume their reign of terror.

The violence ends when local militiamen step in to enforce marshal law. But the order restored is anything but just for the free blacks. The city authorities arrest 300 blacks and no whites; allow Kentuckians to visit jail cells in search of run-aways; re-institute the 1807 requirement that blacks post $500 personal bonds; and seize all weapons held by blacks.

Like the race riots of 1824 and 1831 in the Hardscrabble area of Providence, and in Five Points N.Y. in 1834, the Boston violence in 1836 and 1841 set the stage for bloody times to come in America.