Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 34: America Wins The War Of 1812

1812

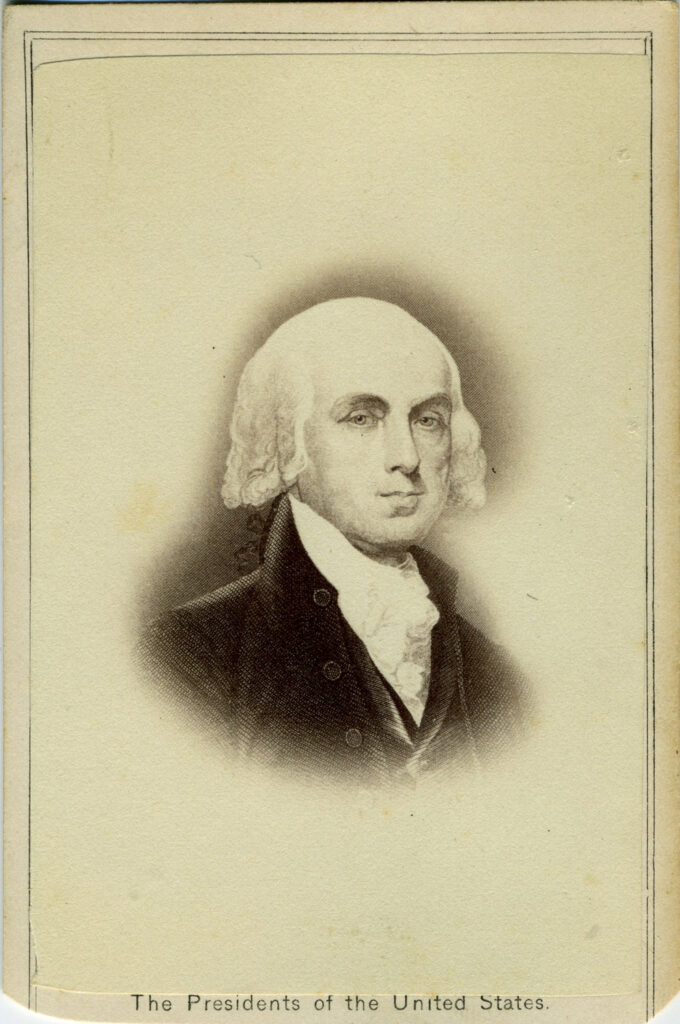

Madison Is Re-elected By A Narrow Margin

With things going badly on the battlefield, Madison faces the prospects of a close race for re election.

Before it takes place, the voting landscape is again altered based on the 1810 Census and the addition of Louisiana to the Union.

The data show that the nation’s population grows by 1810 to 7.240 million, up 36% from 1800.

U.S. Population (millions)

| Year | Total | Whites | Free Blacks | Slaves |

| 1800 | 5.308 | 4.306 | 0.108 | 0.894 |

| 1810 | 7.240 | 5.863 | 0.186 | 1.191 |

| % Ch | +36% | +36% | +43% | +33% |

With the admission of Louisiana in April 1812, America has a total of eighteen states, nine where slave ownership is permitted and nine where it is banned.

America’s Eighteen States As Of 1812

| Region | Slavery | States |

| South | Yes | Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana |

| Border | Yes | Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky |

| North | No | New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont |

| West | No | Ohio |

With each state allotted two senators, the upper chamber totals 36 members.

Apportionment Of Senate Seats After The 1800 Census

| Total | South | Border | North | West | |

| 1790 | 26 | 8 | 4 | 14 | 0 |

| 1800 | 32 | 10 (Ten) | 6 (Ky) | 16 (Vt) | 0 |

| 1810 | 34 | 10 | 6 | 16 | 2 (OH) |

| 1812 | 36 | 12 (La) | 6 | 16 | 2 |

The House allocations are more complicated. As people move from east to west, population shifts vary from state to state, affecting reapportionment. In the House, a total of 7 new seats are added between 1810 (prior to the Census update) and 1812 (after it). The North picks up five seats; the South loses seven; and the migration of settlers into Kentucky almost doubles Border state representation.

Apportionment Of House Seats After The 1800 Census

| Total | South | Border | North | West | |

| 1790 | 65 | 23 | 7 | 35 | 0 |

| 1800 | 106 | 38 | 11 | 57 | 0 |

| 1810 | 175 | 65 | 11 | 92 | 7 |

| 1812 | 182 | 58 | 21 | 97 | 6 |

In turn, the add-up of senate seats (36) and house seats (182) yields a total of 218 votes in the Electoral College for the 1812 presidential race, assuming all delegates cast ballots. The nine non-slave states account for 121 or 56% of the total.

Apportionment Of Electoral College Votes As Of The 1812 Election

| Total | South | Border | North | West | |

| 1812 | 218 | 70 | 27 | 113 | 8 |

The Federalists have high hopes of making a political comeback by throwing Madison out of office.

This possibility has been gaining credibility as cracks appear in the Democratic-Republican party over the failure to resolve tensions with France and Britain. When the initial Congressional Caucus meets in May, 1812, only 86 of the party’s 134 House and Senate members participate, although they do nominate Madison. The question then turns to choosing a Vice-Presidential candidate to replace George Clinton who has recently died in office. Many favor his nephew, DeWitt Clinton, currently serving his third term as Mayor of New York city. But Clinton fails to jump at the chance, and the they end up choosing Elbridge Gerry former Governor of Massachusetts, recently famous for redrawing district voting boundaries in his state (“gerrymandering”).

Soon enough it becomes clear why DeWitt Clinton has passed up the Democratic-Republican nomination – when the Federalists slate him at the top of their ticket!

He is 43 years old, a former U.S. Senator, and master of New York politics. In 1812 he has already begun to lobby for a project that will forever be associated with his name – construction of the 325 mile Erie Canal, linking inland Albany with the port at Buffalo.

As expected, the campaign revolves around the embargos and the war, with the Democratic Republicans defending their record and the Federalists attacking. In the North, Clinton focuses on the economic damage caused by Madison’s trade policies; in the South, he assails the President for mishandling the war effort.

After General Hull’s embarrassing losses in the west, it is only a few successes by the U.S. Navy in the Fall that restores some public faith in Madison, prior to the election.

The Federalist’s strategy almost succeeds. Clinton wins 49% of the popular vote, along with 89 of the total 217 electoral ballots cast. Madison dominates the South and gets a crucial win up North in Pennsylvania, to insure a second term.

Results Of The 1812 Presidential Election

| 1812 | Party | Pop Vote | Electors | South | Border | North | West |

| James Madison | Dem-Rep | 140,431 | 128 | 70 | 18 | 33 | 7 |

| DeWitt Clinton | Federalist | 132,781 | 89 | 0 | 9 | 80 | 0 |

| Rufus King | Federalist | 5,574 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 278,786 | 217 | 70 | 27 | 113 | 7 | ||

| Needed To Win | 109 |

Control over both chambers of Congress remain with the President, although Federalists dramatically strengthen their hand in the House.

Congressional Election Of 1812

| House | 1811 | 1813 | Chg |

| Democratic-Republicans | 107 | 114 | 7 |

| Federalist | 36 | 68 | 32 |

| Senate | |||

| Democratic-Republicans | 30 | 28 | (2) |

| Federalist | 6 | 8 | 2 |

| President | Mad | Mad | |

| Congress # | 12th | 13th |

Meanwhile, in the Congress, the elections of 1810 and 1812 mark a profound “changing of the political guard” at the national level – with Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster rising to leadership positions.

Madison’s second term will be dominated by the war with Britain and some adjusted thinking about the virtues of a standing army and a federal bank.

Key Events: Madison’s Second Term: March 4, 1813, To March 4, 1817

| 1813 | |

| March 11 | Tsar Alexander offers to negotiate peace, but Britain rejects the overture |

| April 27 | Americans capture and burn Canadian capital of York on Lake Ontario |

| Aug 30 | Opening of Creek War provokes Andrew Jackson to call up Tennessee militia |

| Sept 10 | Captain Oliver Hazard Perry wins major naval battle at Ft. Erie |

| Sept 18 | British evacuate Ft. Detroit after Perry controls Lake Erie |

| Oct 5 | Harrison defeats fleeing British at Battle of Thames; Tecumseh killed. |

| Nov 4 | British PM Castlereagh suggests negotiations; Madison picks JQ Adams and Clay to lead. |

| Nov 16 | Blockade of American ports along Atlantic coast extended and intensified |

| Dec 18 | Ft. Niagara falls to British forces |

| 1814 | |

| Jan 27 | Congress agrees to calling up a 62,000 man army, after Madison asks for 100,000. |

| Feb 9 | Treasury Secretary steps down to travel to England for peace negotiations |

| Mar 27 | General Andrew Jackson ends Creek War with victory at Horseshoe Bend |

| Mar 31 | Madison recommends repeal of the Embargo and Non-Importation Acts |

| April 6 | Napoleon is overthrown in France, freeing British forces to fight in America |

| July 3 | General Jacob Brown’s forces move north to take Ft. Erie from the British |

| July 5 | An American victory at Chippewa slows the British advance south to re-take Ft. Erie |

| July 22 | Harrison’s Treaty of Grenville ends war with the dead Tecumseh’s confederation |

| July 25 | Britain’s move toward Ft. Erie is delayed in the war’s bloodiest battle at Lundy’s Lane |

| August 8 | Direct peace negotiations begin in northern Belgium at Ghent |

| Aug 24 | In the east, American forces are routed at the Battle of Bladensburg |

| Aug 25 | The British occupy Washington DC and burn parts in return for the earlier sack of York |

| Aug 27 | Madison names James Monroe as interim War Secretary replacing Armstrong |

| Sept 14 | Baltimore withstands attacks by land and sea; Key writes Star Spangled Banner poem |

| Sept 17 | British abandon siege of Ft. Erie, ending war activities in the Canadian theater |

| Dec 15 | Federalists issue secession threat at the Hartford Convention |

| Dec 24 | The Treaty of Ghent officially ends the War of 1812 |

| Year | Francis Lowell opens first U.S. textile mills, in Massachusetts |

| 1815 | |

| Jan 8 | After the war is officially over, Andrew Jackson whips the British at New Orleans |

| Feb 7 | Secretary of Navy position in the cabinet is created |

| Mar 3 | Congress restores open trade with all nations |

| June 18 | Napoleon is defeated at Waterloo |

| Aug 5 | Captain Stephen Decatur negotiates peace treaty with Tunis to end naval conflicts |

| Dec 5 | Madison urges congress to support a second US Bank, a strong army, infrastructure work |

| 1816 | |

| Jan 8 | Clay and Calhoun now support US Bank, while Webster opposes it. |

| Mar 14 | Congress approves Second Bank of US, to open January 1, 1817 |

| Mar 16 | Democratic caucus nominate James Monroe over William Crawford for presidential |

| April 11 | Blacks in Philadelphia open African Methodist Church, first independent of white control |

| April 27 | Tariff Act passed to protect American manufacturing, with Clay and Calhoun supporting |

| Oct 27 | William Crawford named Secretary of the Treasury |

| Dec 4 | James Monroe is elected president |

| Dec 11 | Indiana is admitted to the Union (#19) |

| Dec 28 | American Colonization Society founded to return Africans to Liberia |

| 1817 | |

| Jan 1 | Second Bank of the US opens in Philadelphia |

| Mar 3 | Madison vetoes a bill to spend Federal funds on infrastructure, calls it unconstitutional |

June 4, 1812 to January 15, 1815

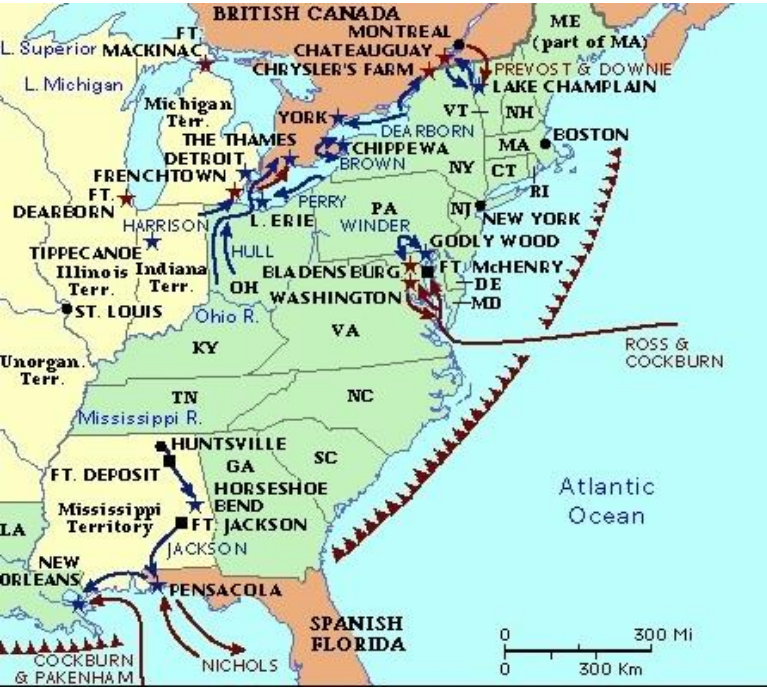

The Three Theaters Of War

America’s War of 1812 – or “Mr. Madison’s War,” as it is called by the Federalists – will drag on for two and a half years before a truce is signed.

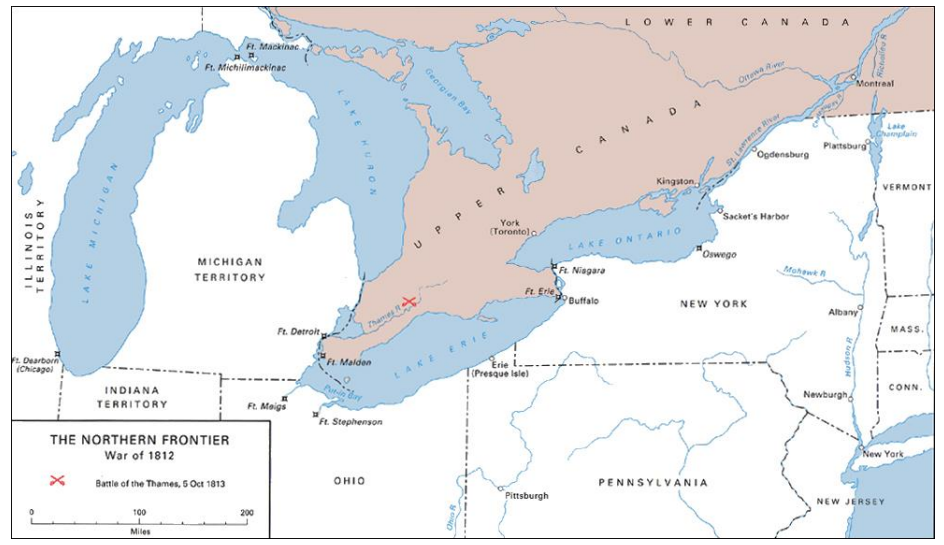

It is fought on land and water in three separate theaters and phases:

- Along the Canadian border – with the U.S. trying to invade north, and Britain, with certain tribal allies, threatening territories from Ohio to Michigan.

- On the Atlantic coast – featuring the British naval blockade and eventually leading to the short-lived thrusts against Washington and Baltimore.

- In the deep South – culminating in a landmark battle around New Orleans.

It will end when both sides recognize that the costs of continuing to fight outweigh the realistic gains left to be had.

Fall to Winter 1812

The War Along The Border Is Stalemated

What Madison and Secretary of War Eustis expect to be easy victories along the western edge of Lake Erie around Ft. Detroit, have turned into a string of humiliating defeats, capped by the August 16 surrender of the garrison and the sack of General William Hull.

The next American attack takes place on October 13, 1812, some 200 miles to the east of Detroit at Queenston Heights, just north of Niagara Falls. It pits a new U.S. commander, General Stephen Van Rensselaer and his 3500 troops against some 1300 British regulars and Mohawk warriors under Major General Isaac Brock, who had thrashed Hull eight weeks earlier.

Van Rensselaer is a political appointee, with limited training in warfare. His attack is poorly planned, an attempt to move from the east, via Lewistown, across the Niagara River and up a 300 foot incline to the entrenched British defenders. As the American cross over by boats, they come under withering fire from the British. Van Rensselaer fights heroically, while being hit six times by musket balls. But only a fraction of his forces cross the river, while the bulk cower in safety on the other side. Finally, those who crossed are forced to surrender.

The Americans suffer 270 killed or wounded and another 800 captured; British losses are around 100 men, most notably General Brock, who dies leading a charge. Van Rensselaer survives his wounds, but resigns his command.

These reversals drive increased criticism of Adams’s overmatched Secretary of War, William Eustis. Madison wishes to replace him with Secretary of State, James Monroe, a Revolutionary War combat veteran, but Monroe declines. So instead, on January 13, 1813, Madison chooses John Armstrong, former Revolutionary War fighter, U.S. Senator from New York, and ambassador to France. But Armstrong too is a controversial figure. The senate confirms him by a narrow 18-13 margin, and he too will be replaced 18 months later, for failing to defend Washington.

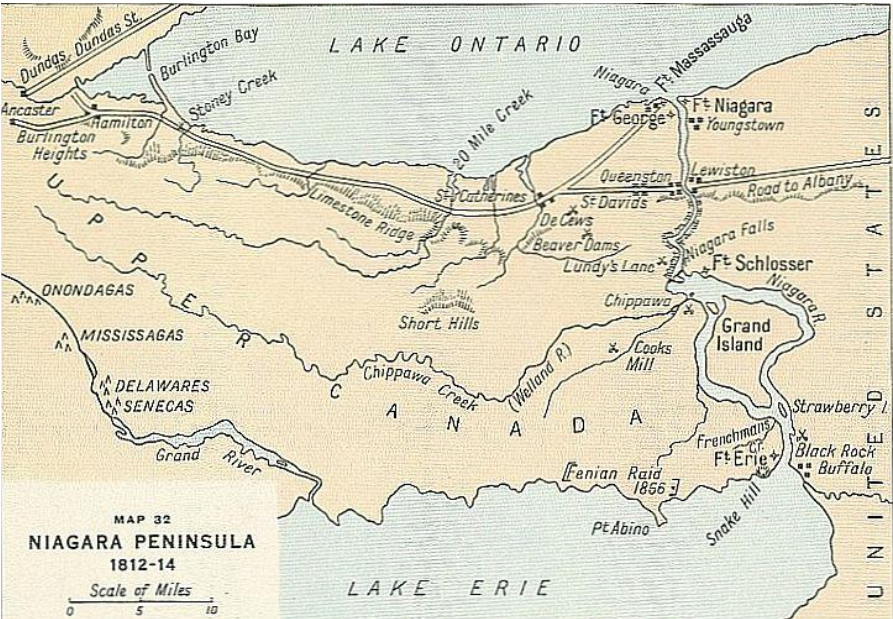

Spring to Fall 1813

America Scores Victories At York, The Niagara Forts And Detroit

It is not until the spring of 1813 that fortunes begin to turn for the Americans in the Canadian theater. The strategy belongs to Armstrong, and it involves gaining control over Lake Ontario.

On April 27, 1813, General Zebulon Pike, the western explorer, sails from Sackett’s Harbor along with 1700 troops to capture the provincial capital town of York (Toronto), situated on the northwest edge of the lake. The disorganized British defenders are quickly overwhelmed, although Pike is killed when they blow up their own magazine to keep it out of American hands. Over the next two days the U.S. forces plunder and set fire to private homes and to the Legislative Assembly – a favor the British will return 16 months later in Washington.

Once York is secured, the American forces turn south to the two key British forts along the Niagara River, Ft. George on the southern shore of Ontario and Ft. Erie some 25 miles below it on Lake Erie.

The defenders of Ft. George expect the Americans to bombard and attack from their base at Fort Niagara on the east side of the river. But instead they come in landing craft on Lake Ontario, led by Lt. Colonel Winfield Scott, whose gallantry in the battle earns him lasting fame.

On May 27, the British commander, fearing encirclement, abandons Ft. George and retreat south, past Niagara Falls, and toward Ft. Erie.

Ft. Erie is the oldest British bastion in Ontario, and it is supported by royal navy vessels under Commander Robert Barclay. On the morning of September 10, 1813, he steers his six ship flotilla into a line of battle engagement with nine smaller U.S. ships under Admiral Oliver Hazard Perry. By 3PM, the Americans have won the day, and Perry sends off a message to General William Henry Harrison, leading ground troops against the fort itself:

General. We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop. Yours. Perry

The Battle of Lake Erie is modest in size, but strategically important. It signals America’s growing naval strength and it inhibits potential British and tribal incursion into Ohio, Pennsylvania and western New York.

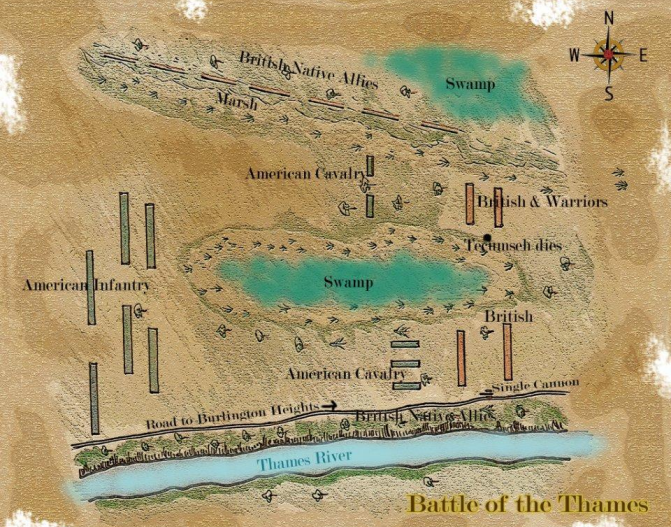

Next comes an equally important victory, back west toward Detroit, in the Battle of the Thames.

With Perry and the American fleet now in control of Lake Erie, the British garrison at Detroit is immediately vulnerable. The commander, Major General Henry Proctor, moves his 800 regulars inland, to the east, along the Thames River. He is accompanied by a contingent of some 500 mostly Shawnee warriors, led by Tecumseh.

Harrison’s forces number 3700 men, and he comes onto the retreating British on October 5, 1813, in a swampy area, some 65 miles upriver, near the town of Thamesville.

The red-coats are half-starved, fire off a few desultory rounds, and then surrender. Not so the Shawnees.

They put up stiff resistance – led by Tecumseh, who dies in battle. His death ends the threat of coordinated tribal and British action against the northwestern territories. And it propels the victorious “Tippecanoe” Harrison even further into the national spotlight.

After Thames, the Americans are happy to let the border war with Canada stabilize.

Winter 1813 to Summer 1814

A Drawn Battle At Lundy’s Lane Ends Fighting On The Border

But now the British refuse to cooperate.

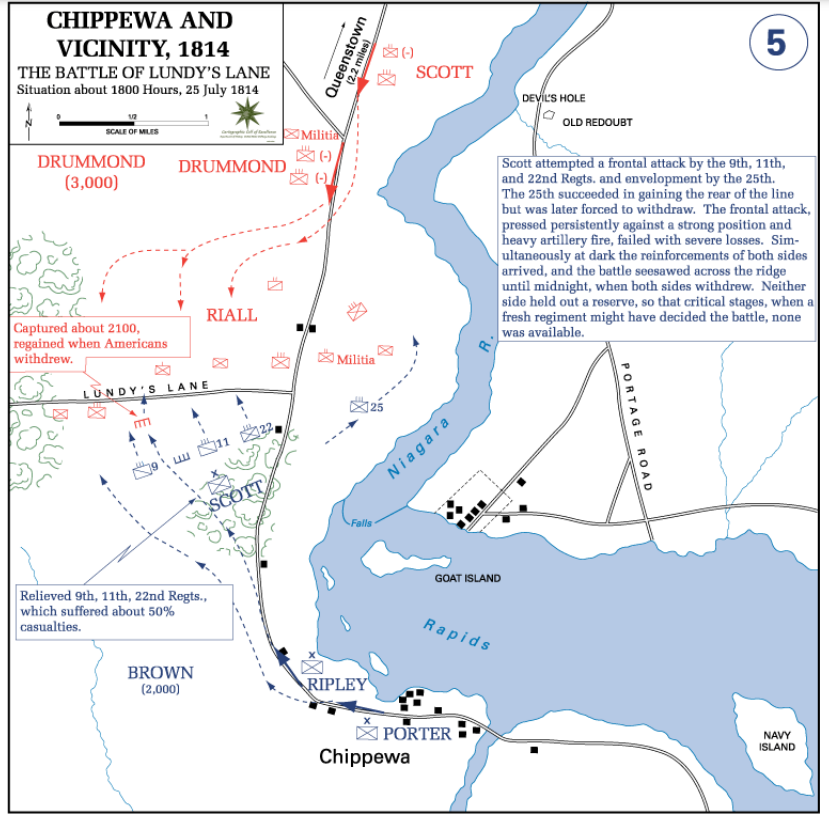

By December 1813, they have retaken control of Ft. George along with America’s Ft. Niagara, and begin to consolidate their forces for a drive south down the Niagara River toward Ft. Erie.

By July 5 they are some sixteen miles north of the fort when their progress is halted by American forces under General Winfield Scott at the Battle of Chippewa. Both sides suffer over 300 casualties before the redcoats withdraw from the field.

Three weeks later, on July 25, 1814, the fighting resumes, this time at Lundy’s Lane in the bloodiest single battle of the war. The site of the clash is in Canada, roughly two miles west of Niagara Falls, the border line between New York to the east and Ontario to the west.

This engagement pits 3500 troops under British Generals Drummond and Riall against 2500 Americans under General Jacob Brown who come out to meet them.

This battle lasts from morning to midnight, ending in a stand-off. Casualties approach 875 men on each side. Among those severely wounded is Winfield Scott, whose military drilling and leadership have earned him the lasting moniker of “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

While both generals claim victory at Lundy’s Lane, the British continue their march south, and begin a siege of Ft. Erie, occupied since July 13 by the U.S. troops under General Edmund Gaines. The siege lasts for a month, before the British lift it on September 17, 1814.

At this point the conflict along the Canadian border is essentially over.

The easy victories that Madison expected in 1812 have never materialized. However, the Americans have proven again that they can hold their own with Great Britain, even in modest naval actions like the Battle of Lake Erie.

And, with the death of Tecumseh, they have diminished the threat of a tribal coalition, backed by the British, impeding westward expansion from Ohio to the Mississippi.

Key Events Along The Canadian Border: War Of 1812

| 1812 | July 12 Americans under Hull cross Detroit River into Canada |

| July 17 British capture Ft. Mackinac in Hull’s rear | |

| Aug 16 Hull surrenders Ft. Detroit without a shot fired | |

| Oct 13 British win Battle of Queensland Heights, near Niagara Falls | |

| 1813 | Jan 13 Secretary of War Eustis resigns |

| Jan 18-23 Battle of Raisin River (Monroe, MI), US prisoners massacred | |

| April 27 US captures York (Toronto) and plunders the town | |

| May 27 Americans capture Ft. George on Lake Ontario | |

| Sept 10 US Admiral Perry wins Battle of Lake Erie | |

| Oct 5 WH Harrison wins at Thames, killing Tecumseh | |

| Dec 19 British fight back, taking Ft. George and Ft. Niagara | |

| 1814 | July 13 Americans occupy Ft. Erie |

| July 25 bloody battle at Lundy’s Lane a stand-off | |

| Aug 14 British begin siege of Ft. Erie | |

| Sept 17 British retreat from siege |

Summer 1812 – Summer 1813

Britain Routes American Forces On The Atlantic Coast

Britain’s Royal Navy dominates the second theater of war – on the seas off the Atlantic coast – with a blockade that essentially shuts down America’s international commerce, and leads to a secession threat by the New England states.

When hostilities break out, the British have 85 warships already patrolling American waters to enforce their ban on cargoes headed toward Napoleon’s France.

The United States, on the other hand, begins with a fleet of 21 ships, composed of:

- 8 “frigates,” also 3 masts, but lighter and faster with one deck of 28-44 guns.

- 13 smaller escort ships, war sloops, brigs and schooners, with 12-18 guns apiece.

- 0 “ships-of-the-line,” the three-masted, multi-decked 74 gunners built for broadside attacks.

With this limited force, all the Americans can hope to do is occasionally break out of their ports and go after an isolated foe.

And one such opportunity arises early in the war, on August 19, 1812, when the frigate USS Constitution – 44 guns and 456 sailors under Captain Isaac Hull – wins an intense five hour battle with the 38-gunned HMS Gurriere, off the coast of Halifax. This victory, the first of five that the Constitution will record over British warships, earns the frigate its lasting sobriquet, “Old Ironsides.”

But this British defeat proves an anomaly, and the Royal Navy gradually expands it stranglehold on the east coast sea lanes. By the end of 1812 they have shut down American shipping from the Chesapeake Bay, marking the Virginia coast, through South Carolina.

In April 1814, they extend their tight blockade north into New England, which further stirs opposition to Madison’s conduct of the war in Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Both states have refused to place their militia under the federal War Department, and, in turn, Madison has denied them federal funding support for their own defense.

This further prompts the question: is the government effectively protecting the nation?

In August 1814, both the New Englanders and the entire nation are reminded of the mortal danger posed at any moment by the powerful British navy.

By this time, the war against France has turned and Britain is able to free up more land troops to fight the Americans. One of these is the Dublin born Major General, Robert Ross, who has fought valiantly alongside Wellington, and is now given command over all army troops.

Along with his naval counterpart, 3-star Vice Admiral George Cockburn, Ross plans a two pronged assault aimed at his opponent’s heart, the capital city of Washington.

The plan involves a naval flotilla consisting of 4 ships-of-the-line and 20 more frigates and war sloops, under Admiral Alexander Cochrane, along with transport boats to carry Ross and his 4,400 men, mostly veteran Royal Marines to land.

On August 19, Ross disembarks at Benedict, Md. and begins marching northwest toward the town of Bladensburg, about 10 miles above Washington, on the east branch of the Potomac River. Once there they encounter an American force consisting of 6500 Maryland militia and 400 U.S. Regulars under Brigadier General William Winder.

The August 24, 1813 Battle of Bladensburg proves to be one of the greatest routs in American military history. Winder has aligned his troops poorly and they are decisively thrashed by Ross. Lacking any pre-planned line of retreat, the U.S. forces turn tail and make a dash for Washington, DC, 10 miles to the southwest. This flight, which includes both President Madison and Secretary of State Monroe, is immortalized as “The Bladensburg Races” in a satiric British poem in 1816.

Away went Madison, away Monroe went at his heels,

And all the while his laboring back, a merry thumping feels.

Summer To Fall 1813

British Sack Washington But Are Turned Back At Baltimore

But the worst is yet to come on this day. At Washington City.

Secretary of War Armstrong is certain that the British will never reach the capital, and has made essentially no preparations to defend it.

Ross’s troops arrive in the capital by evening on the 24th and are shot at when they approach under a truce flag. This leads to a 26 hour rampage in which the Capitol, the White House and the US Treasury are all pillaged and burned – in return, the British claim, for similar destruction of their provincial capital of York in April, 1813.

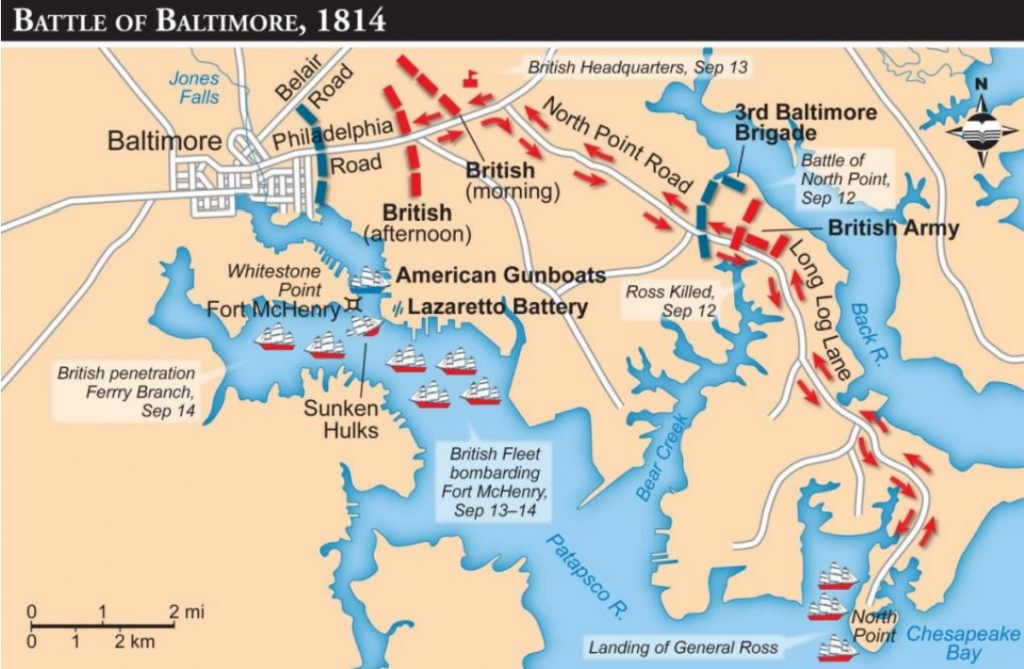

With the US government stunned and momentarily homeless, Ross and his troops exit Washington to rejoin Admiral Cochrane’s flotilla on August 26th and take aim at their second objective, capturing the critical port city of Baltimore.

On September 12, Ross disembarks at the town of North Port, on Chesapeake Bay, twelve miles southeast of Baltimore. But now the Americans are ready for him.

General John Stricker has laid out a strong defensive position between North Port and redoubts around the city, marked by tidal swamps and creeks that force the British to funnel through a narrow strip of land, where his 3200 Maryland militia men wait.

While the battle ends after two hours with the Americans withdrawing, the British suffer a crucial loss when General Ross is mortally wounded by a musket round that strikes him in his right side.

On September 13, the Battle of Baltimore hangs in the balance.

The now 5,000 strong British ground troops, under Colonel Arthur Brooke, encounter very stiff resistance at Hampstead Hill from what has grown to be 11,000 militiamen, led by Generals Stricker and William Winder. At 3AM, Brooke concludes that the initiative is lost, and begins to withdraw his men.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy is encountering similar opposition on the water.

Admiral Cochrane sails his 19 ship flotilla into Baltimore Harbor, briefly exchanges cannon fire close up to the American defenders in Ft. McHenry, and then anchors just beyond range of the fort’s guns.

He then proceeds to bombard the Americans for almost 25 straight hours, until daylight on the 14th– when the Americans send aloft an oversized flag signaling their ongoing presence within the Fort.

In the harbor, a 35 year old American lawyer named Francis Scott Key, on board a British ship to conduct a goodwill mission for President Madison, watches the bombardment through the rainy night, wondering what the morning of September 14 will bring.

At dawn, Key glimpses the Stars and Stripes still flying over the ramparts. The Americans have held Baltimore, Key is moved to capture the moment in words.

Oh say does that star spangled banner yet wave o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

After the stalemate along the Canadian border and in the harbor at Baltimore, both nations are growing weary of the now two year old conflict. The war in the two northern theaters is over.

But one more great battle remains to be fought in the third theater of the war, the deep South, at New Orleans.

Key Events On The Atlantic Coast: War Of 1812

| 1812 | Aug 19 USS Constitution defeats HMS Guerriere |

| Nov English ships blockade South Carolina coast | |

| Dec Blockade extended to Chesapeake and Delaware Bays | |

| 1813 | Mar Blockade reaches Long Island and Mississippi |

| 1814 | April Blockade extended to New England |

| Aug 24 British invade and burn Washington | |

| Sept 13- 14 US stops British at Ft. McHenry and Baltimore |

Spring 1814 To January 8, 1815

U.S. Triumphs Across The South End The War

One figure dominates events in the deep South during the War of 1812: Andrew Jackson, Major General of the Tennessee militia.

Jackson is 45 years old when the second conflict with Britain begins. He has been in the militia since fighting in the Revolutionary War at age thirteen and has lived on the western frontier since 1787. He is a natural leader, the right man to lead American forces in the interior.

He does so in the two important battles that take place in the deep South – one at Horseshoe Bend in what will become Alabama, the other at the port of New Orleans.

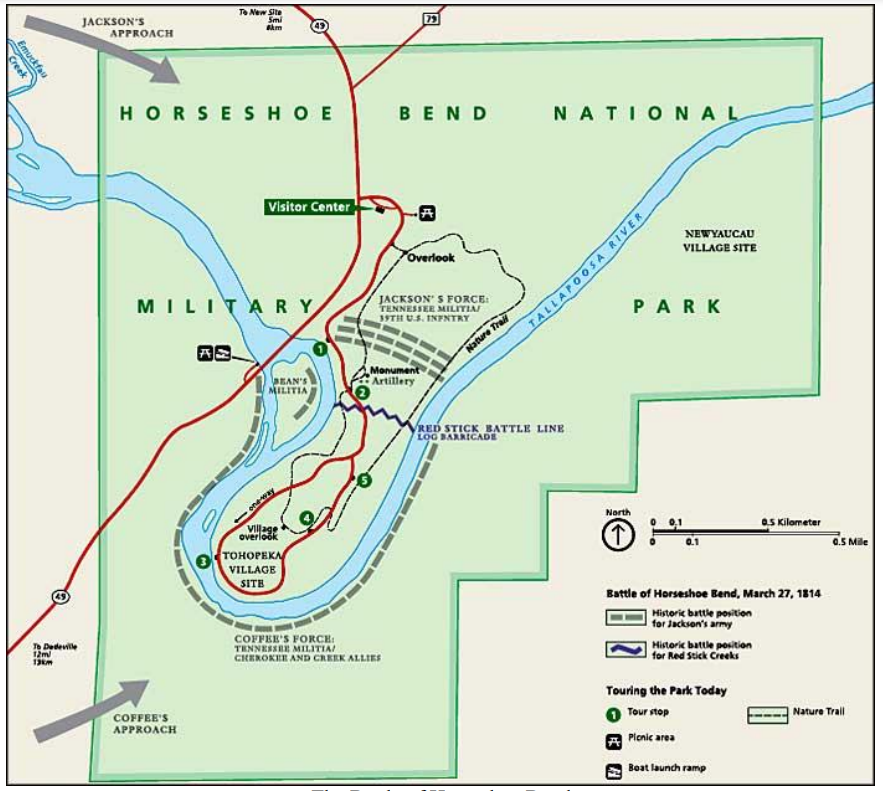

The war is nearing the two-year mark on March 27, 1814, when Jackson approaches an Indian camp nestled in a bend in the Tallapoosa River. The General is accompanied by a force of 2,700 militia and another 600 Cherokee and Choctaw tribesmen.

The encampment they encounter consists of some 700 “Red Stick” Creeks, the one tribe that Chief Tecumseh has previously recruited to fight alongside his Shawnees and the British.

While the Creeks feel safe surrounded by the river, the fact is that they are trapped in a cul-du-sac, with only one narrow pathway in and out over open ground. When the Red Sticks throw up breastworks to defend this camp entrance, Jackson attacks it repeatedly with artillery and charges and also sends probes across the river into their rear. After some five hours of battle, the Creeks disintegrate, with upwards of 80% of their number being killed, wounded or captured.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend ends the Creek resistance, and at the Treaty of Fort Jackson on August 9, the Nation cedes 23 million acres of their land to the U.S. In addition to Jackson, two other American fighters – Sam Houston and Davey Crockett – both win fame from this fight.

Ironically the other memorable battle in the deep South occurs after diplomats from Britain and the U.S. have signed the peace Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, ending the war.

The word, however, does not reach America before the British attack is under way.

In late November General Edward Packenham, a veteran of the Napoleonic wars, and brother-in law of Wellington, sails from Jamaica with 18,000 crack troops to join the American campaign – his objective being to capture, hold and then govern the city of New Orleans.

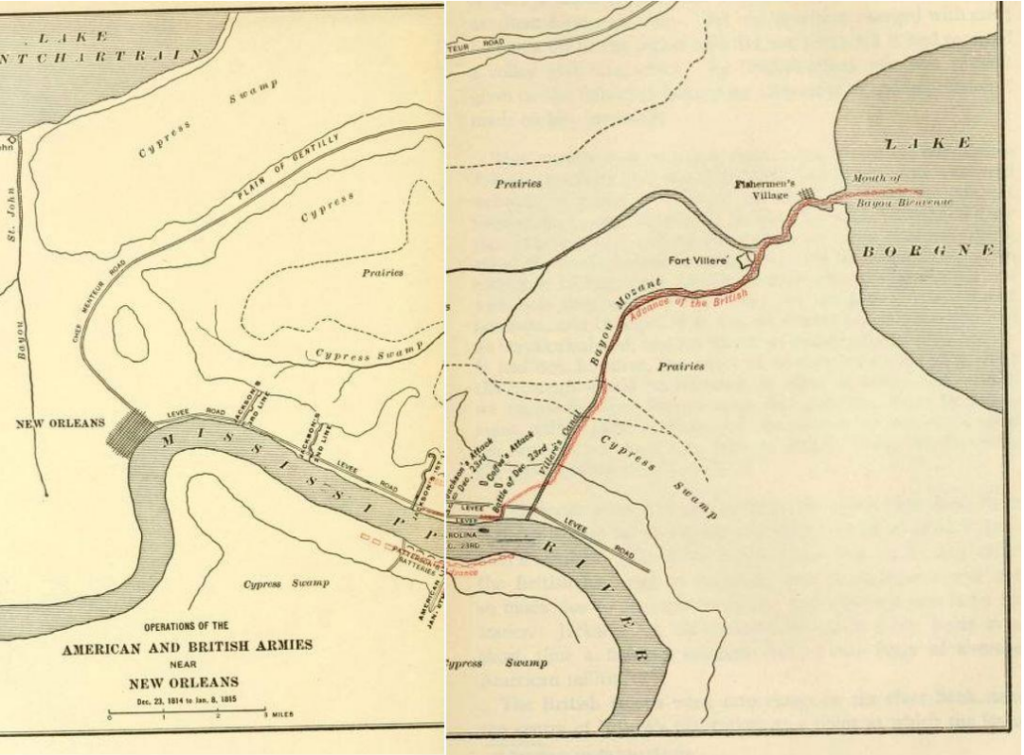

But Packenham and Admiral Alexander Cochrane first need to choose how best to approach the city. One path is to send British ships up some 100 twisting miles up the Mississippi, past Ft. St. Philip and other outposts, and attack from the south to north.

The other, which Cochrane chooses, is to locate the fleet in the Gulf of Mexico, just below and to the east of Lake Pontchartrain – and attack overland for some 15 miles from the east.

On December 12, Cochrane anchors on Lake Borgne at Fisherman’s Village, and Packenham disembarks.

Packenham does not, however, race directly toward the prize, instead choosing to proceed at a leisurely pace to set up a base camp and prepare his eventual assault.

This delay gives General Jackson, who doesn’t arrive in New Orleans until November 30, the time he needs to organize his opposition.

When he hears on December 23 that Packenham’s advance guard of 1800 troops under General John Keane have reached the Mississippi at Lacostes Plantation, some 7 miles downriver from the city, he sets in motion a three-pronged attack against the encamped British.

His rallying cry at the moment is pure Jackson, the leader of men into battle: “By the Eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil.”

The battle on the 23th proves a stand-off, but it again slows down the British move north to New Orleans and gives Jackson even more time to build defensive positions.

On December 28, Packenham sends out probing attacks to assess the challenge which lies ahead for him.

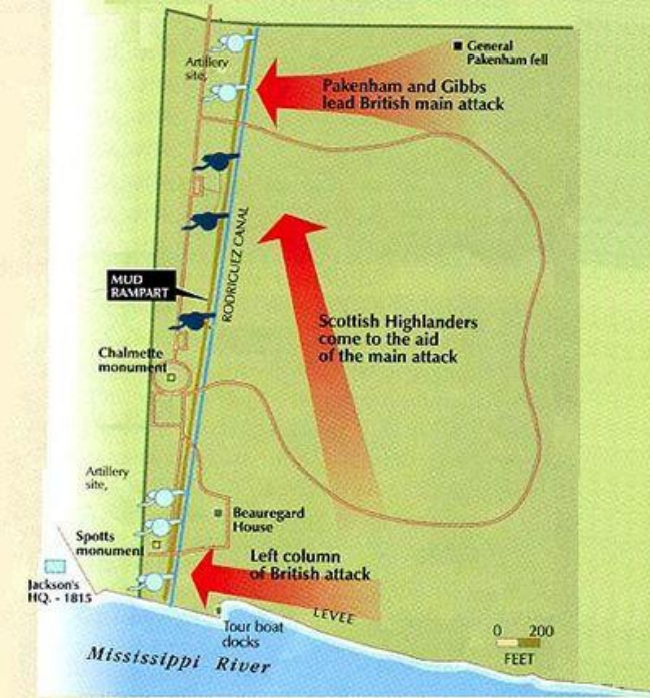

It is not until January 8, 1815 – with all 8,000 troops on hand – that he advances from south to north against the “Jackson Line” set up at Chalmette Plantation, five miles below New Orleans.

Jackson’s main position is flanked on his right by the Mississippi River and on the left by swampland. He has arrayed his 4,000 militia and 16 cannon behind breastworks that run roughly a thousand yards in from the river to the swamp. Across the riven, he has also stationed a force to protect his right flank.

Packenham’s strategy is to drive two separate columns of redcoats straight at Jackson, while also sending a detachment across the river to try to enfilade the Americans on their right. But the later maneuver develops too slowly for the General.

So he sends his lines forward, as the overnight fog lifts on the field leading to the US positions. First, it is General Gibbs with 3,000 men on the British right, who try to force Jackson, but are turned back well short of the ramparts.

Seeing this repulse, Packenham himself leads Keane’s left-side column of 900 Highlanders in an oblique march across the face of the American guns – to join Gibbs in a second charge. But chaos accompanies this assault, as the British command is cut down one by one.

Packenham is wounded by gunfire in the left knee, then the right arm, and finally is hit by a shell that severs an artery in his leg, bleeding him out in minutes. Gibbs receives a mortal wound in the neck and Keane is also wounded and carried from the field.

Still the British make a third and final assault on their right, led by a Major, the highest ranking officer left. This time they penetrate all the way into Jackson’s lines, before being turned back – effectively ending the battle.

Jackson has triumphed and saved New Orleans!

And the casualty figures prove the size of the victory, the defensive-minded Americans suffering 101 killed, wounded, and captured, to 2,037 for the attacking British.

After the battle, Andrew Jackson is hailed as a national hero, and begins his trail toward the presidency. Edward Packenham, a hero of the day in his own, has his body packed into a preserving cask of rum and shipped home to Ireland for burial.

December 24, 1814

The Treaty Of Ghent Brings Peace

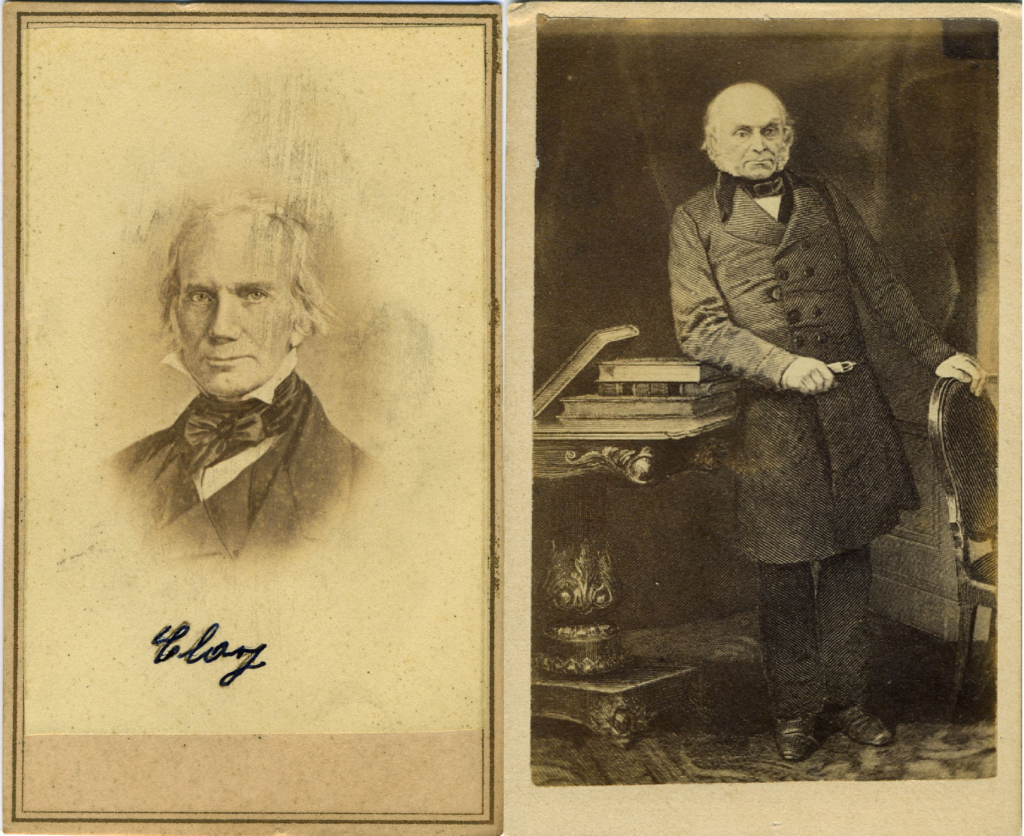

On December 24, 1814, two American emissaries – John Quincy Adams, serving as Ambassador to Russia, and Speaker of the House, Henry Clay – sign the Treaty of Ghent with British counterparts, thus ending the War of 1812.

The toll on both sides has been high. Britain has lost 1600 killed, 3700 wounded and another 3300 lost to disease; American losses are even higher, 2260 killed, 4500 wounded and 8000 dead from illnesses. In monetary terms, the bill is roughly $100 million for each side.

Estimated Casualties Of America’s Two Wars With Britain

| Revolutionary War | Years | Killed | Wounded Disease | Total | |

| America | 1775- 1783 | 8,000 | 25,000 | 17,000 | 50,000 |

| Britain | 4,000 | 12,000 | 8,000 | 24,000 | |

| Germans | 1,800 | 3,700 | 1,700 | 7,500 | |

| War of 1812 | |||||

| America | 1812- 1815 | 2,260 | 4,505 | 12,740 | 20,000 |

| Britain | 1,500 | 3,700 | 3,300 | 8,500 |

And to what end, the costly War of 1812?

Neither side has won new territory from the other, and a major cause of the war – the British practice of seizing American sailors – has ceased after Napoleon’s defeat in Russia in 1812.

Still, the United States has some positive things to show for the 30-month conflict:

- The threat to western settlers from Tecumseh’s confederated Indian tribes affiliated with Britain has been diminished.

- A series of future national leaders have emerged from the events, Harrison, Scott and Jackson on the military side, Henry Clay in particular on the political front.

- Of greatest importance, America has once again demonstrated to itself, and to the world, that it has the might and will to hold its own against the powerful British lion.

December 15, 1814 – January 5, 1815

The Spector Of Secession Arises At The Hartford Convention

One more fall-out from the war is the specter of secession, in this case pitting the Northeast states against the South.

From the opening debate in congress onward, the old-time Federalists of New England have stood in firm opposition to “Madison’s War” — a war which has cost their region dearly in terms of lost manufacturing and shipping revenues and left them feeling vulnerable at any moment to a Royal Navy invasion.

The sack of Washington and the threat to Baltimore over the summer of 1814 heighten their fear and anger.

A powerful trio of Massachusetts’s men are particularly outspoken critics of Madison’s conduct of the war and its effect on the economy. They include Timothy Pickering, former Secretary of State in Washington’s cabinet, the Boston lawyer, John Lowell, Jr., and Josiah Quincy, later president of Harvard University.

Others join them in the call for New England to band together and challenge federal operations ad policies.

These ideas are aired at the “Hartford Convention,” which is gaveled to order in the Connecticut capital on December 15, 1814.

The convention is chaired by George Cabot, a well-known seaman, merchant, and ex-Senator from Massachusetts.

A total of twenty-six delegates attend, representing five states – Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont and Massachusetts. The meetings are held in private over a three-week period and result in a report to be delivered to Congress.

At first glance this final document will appear fairly moderate. It suggests that five Amendments be added to the U.S. Constitution:

- Prohibit trade embargoes lasting over 60 days;

- Require a 2/3rd vote majority to declare war, impair foreign trade, admit new states.

- Limit future presidents to one term.

- Insure that future presidents are from different states than the incumbent.

- End the unfair voting advantage the South has in the House owing to the 3/5th slave count.

It is the fifth amendment that quickly stirs regional tensions.

It does so by re-opening an old wound — the controversy at the 1787 Constitutional Convention whereby the South was “allowed to count their slaves as semi-citizens” (i.e. the 3/5ths Enumeration Clause).

The North never quite lets go of this concession, and, at Hartford, it resurfaces as the source of an “unfair voting advantage” enabling the South to wield more than its fair share of power in Washington.

The result being two more Virginia presidents in a row – Jefferson and Madison – who have imposed trade embargos and brought on a war that has been ruinous to New England’s well being.

In the face of these “unconstitutional infringements” on the region’s wishes, the only recourse left would seem to be breaking with the union or refusing to obey self-destructive laws.

Ironically this latter option is exactly what John Calhoun and the South will echo down the road, first over the tariff and then over slavery. The “right” of the states to nullify federal statutes detrimental to their well-being.

However, by the time the Hartford Convention report reaches Washington, the outlook for New England’s shipping economy is looking up. The war with Britain has ended, and what’s left of the French army is straggling back from Moscow. Prospects are suddenly hopeful for a natural return to free and secure trade on the high seas.

Still the proposed amendments from Hartford will have a residual political effect when the Democratic-Republicans cite them as evidence of Federalist antipathy toward the South, and possible disloyalty toward the Union.