Section #15 - Northerners rebel after the 1854 Kansas- Nebraska Bill reneges on the Compromise of 1820

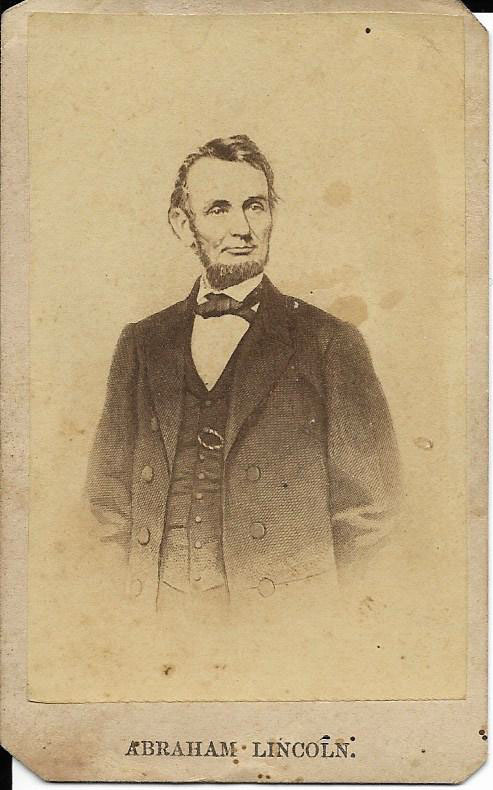

Chapter 181: Abraham Lincoln Re-emerges On The Political Stage

October 3, 1854

Lincoln And Douglas Debate The K-N Bill In Springfield

Since exiting his single term in the U.S. House in March 1849 convinced that his political career is over, Abraham Lincoln has returned to his home in Springfield, Illinois, to resume his law practice, and help raise his growing family, which, by 1854 includes his three surviving sons: Robert, Tad and Willie.

In April 1854, he is again off “riding the circuit” for ten solid weeks, arguing cases in seven towns covering a route of some 400 miles.

Only this time his routine is disrupted by news of uprisings across the state aimed at his old rival, Stephen A. Douglas, for passage in May of the Kansas Nebraska Act.

The lawyer in Lincoln sees the act as an egregious violation of the 1820 Missouri Compromise, prohibiting slavery above the 36’30” line in all Louisiana Purchase territorie. Beyond that, the humanitarian in Lincoln regards any further spread of slavery as a moral stain on the nation. As he says repeatedly in his life:

If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.

At first his response is cautious, and targeted at politics in his home state. His loyalty remains to what’s left of the Whig Party, and his first stump speech in August is on behalf of re-electing Richard Yates to a second House term in a district that leans pro-slavery. Reluctantly he himself agrees to run for another term in the state congress from Sangamon County, but with an eye to replacing his Democratic rival, Senator James Shields, in the upcoming election.

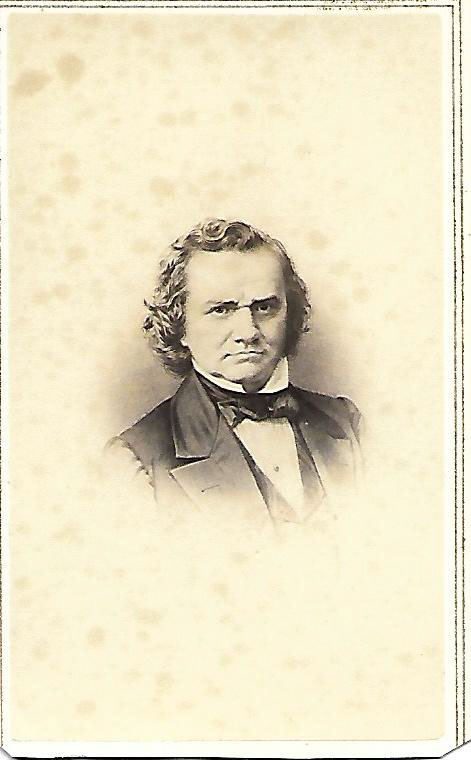

Lincoln is already campaigning across the state in the Fall, when Stephen Douglas initiates his own speaking tour in Illinois to try to deflect mounting Northern opposition to his Nebraska legislation.

Lincoln has known Douglas since their first meeting in Springfield in 1834, and they have been opponents ever since. In 1838 Lincoln stumps for his law partner, John Stuart, in his race against Douglas for a U.S. House seat. They share a platform in the 1840 presidential race, with Lincoln backing the Whig, Harrison, and Douglas, the Democrat, Van Buren. Rumors also have it that Douglas has been a rival for the hand of Mary Todd in 1842 before she marries Lincoln.

Furthermore, Lincoln does not like Douglas. He refers to him as “the least man I ever saw” – a man who “will tell a lie to ten thousand people one day, even though he knows he may have to deny it to five thousand the next.”

Also a note of envy seems at play here, with Lincoln having watched Douglas ascend to national prominence in Washington, while his own destiny seems confined to legal success within the state of Illinois.

But controversy over the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act now gives Lincoln another shot at Douglas after he agrees to deliver three public speeches back in Illinois in September and October, sensing that his home state is quite divided on his bill.

The result is a head-on debate between the two men on October 3, 1854 in Springfield — with the lanky, six foot three inch Lincoln speaking for three hours, and the stocky Douglas, a foot shorter, offering a two hour rebuttal.

Lincoln’s address is noted for his contention that no amount of pleading on behalf of popular sovereignty could possibly justify an outcome where “the monstrous injustice of slavery” was affirmed. The issue was one of moral right and wrong, not one of political process.

Several of the Springfield attendees are impressed by Lincoln’s arguments, and his name is mentioned by those seeking to form an official Republican Party in Illinois. Among them is Owen Lovejoy, brother of the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy, whose murder in Alton, Illinois in 1837, engages both Lincoln and John Brown in the issues surrounding slavery.

Opponents of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill immediately encourage Lincoln to follow his rival’s itinerary and continue the exchanges. While he agrees, Douglas decides that he has had enough for the moment, after telling friends that Lincoln is the “most difficult and dangerous challenger that I have ever met.”

October 16, 1854

Lincoln’s “Peoria Speech” Thrusts Him Into The Political Spotlight

With Douglas declining any further debates, Lincoln goes on to deliver a three-hour speech in Peoria, Illinois, that will alter his destiny.

In it he reprises the history of slavery in America, and, with precise lawyerly logic, lays out the case against the repeal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise. It begins:

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and the propriety of its restoration constitute the subject of what I am about to say. It was a law passed on the sixth day of March, 1820, providing that Missouri might come into the Union with slavery, but that in all the remaining part of the territory purchased from France, slavery should never be permitted.

This 1820 law reflected the wishes of the founding fathers, like Jefferson.

The policy of prohibiting slavery in the new territory originated with Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence.

And as recently as 1849, Douglas publicly applauded it.

In 1849, our distinguished Senator, in a public address, held that: The Missouri Compromise has been in practical operation for a quarter of a century, and has received the approbation of men of all parties in every section of the Union.

Then came the acquisition of new territory from Mexico, and the nation crafted the 1850 Compromise to establish rules governing slavery in the far west.

The Union, as in 1820, was thought to be in danger; and devotion to the Union rightfully inclined men to yield somewhat in points where nothing else could have so inclined them.

Preceding the Presidential election of 1852, each of the great political parties met in convention and adopted resolutions endorsing the compromise of 1850; as a finality – a final settlement of all slavery agitation. And the legislature in Illinois’s endorsed it.

Douglas offered his original Nebraska bill, but then altered it to argue that the 1850 rules set for the far western land should also apply to the 1803 Louisiana Purchase land.

About a month after the introduction of the 1854 Nebraska bill, it is modified to make two territories instead of one; to declare the Missouri Compromise inoperative and void; to allow people who settle establish slavery or exclude it as they may see fit.

In effect, this revised 1854 Kansas-Nebraska law says that the settled law in the 1820 Missouri Compromise was all a great mistake.

But now congress declares this ought never to have been; and the like of it must never be again. The sacred right of self-government is grossly violated by it.

Lincoln disagrees, the great mistake would be to allow the monstrous injustice of slavery to spread any further.

I can not but hate letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska – and allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world where men can take it.

I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world – enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites –and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty – criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

He makes it clear that his cause is not to outlaw slavery in the old South, but to oppose its extension to the west.

And as this subject is part of the larger question of domestic slavery, I wish to make and keep the distinction between the existing institution, and the extension of it, so clear that no honest man can misunderstand me.

Slavery is a national problem and should not be blamed on the southern people.

Let me say I think I have no prejudice against the southern people. When they tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery than we; I acknowledge the fact. If slavery did not now exist amongst them, they would not introduce it.

If he could, he would ship the slaves back to their homeland, but this is not feasible.

When it is said that the institution is very is very difficult to get rid of in any satisfactory way, I understand the saying. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves and then send them to Liberia – to their own native land.

Nor does he believe that the nation is ready for the abolitionist’s solution, freeing all the slaves overnight and assimilating them into white society.

What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially our equals? My own feelings will not admit this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not.

Lincoln admits to the difficulty of finding a solution, other than gradual emancipation.

If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the south.

And the facts are that many former slaves have been gradually emancipated, at great economic sacrifice by their former owners, and on the simple principle that, in their hearts, men know that a slave is not the equivalent of a horse or a cow.

And yet again, there are in the United States 433,643 free blacks. At $500 per head they are worth over two hundred million dollars. How comes this vast amount of property to be running about without owners? We do not see free horses or free cattle running free. How is this? Something has operated on their white owners, inducing them, at vast pecuniary sacrifices, to liberate them. What is this something? Is there any mistaking it? In all cases it is your sense of justice, and human sympathy, telling you, that he poor negro has some natural right to himself – that those who deny it, and make merchandise of him, deserve kickings, contempt and death.

Despite the obvious injustice of slavery, he asks is Douglas isn’t right in arguing that people in the Kansas and Nebraska should have the right to decide for themselves whether to accept or reject it? Only, he says, if one believes that the negro is not a man but a beast.

But one great argument in support of repeal of the Missouri Compromise is still to come. That argument is “the sacred right of self-government.” The doctrine of self-government is right – absolutely and eternally right – but it has no just application as here attempted. It depends on whether a negro is or is not a man. If the negro is a man, is it not a total destruction of self government to say that he shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more that self-government – that is despotism.

If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man making a slave of another.

So, can it be shown that the negro a man? Here Lincoln refers to the Constitution, where southerners themselves have argued that slaves are persons, who should be counted as 3/5th of a white man.

In the control of the government, each State has a number of Representatives in proportion to its number of people, and for this purpose five slaves are counted as being equal to three whites.

Lincoln next addresses what he calls a “lullaby” argument from Douglas, one saying that the weather in the new territory will never allow cotton plantations.

As to climate, a glance at the map shows there are five slave states – Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky and Missouri – and also the District of Columbia, all north of the Missouri compromise line.

He attacks the bill’s gross lack of clarity about “when and how” the slavery question will be resolved.

The people are to decide the question for themselves; but when are they to decide; or how they are to decide; or whether the question is to be the subject to an indefinite succession of new trials, the law does not say. Is it to be settled by the first dozen settlers who arrive there, or is it to wait the arrival of a hundred? Is it to be decided by a vote of the people or a vote of the legislature? To these questions, the law gives no answer.

And he properly foresees an outcome whereby a minority of settlers bring slaves into the territory and, once there, a subsequent majority in opposition cannot dislodge them.

The bill enables the first few to deprive the succeeding many. The first few may get slavery in, and the subsequent many cannot easily get it out. How common is the remark now in the slave states – “if we were only clear of our slaves, how much better it would be for us.

The outcome in Nebraska is important to everyone in the Union.

The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people. This they cannot be, to any considerable extent, if slavery shall be implanted within them.

As he nears the end, Lincoln reiterates his plea – to resist the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and, in so doing, to restore “the noblest political system the world ever saw.”

Fellow countrymen – Americans south as well as north, shall we make no effort to arrest this? In our greedy chase to make profit of the negro, let us beware, lest we cancel and tear to pieces even the white man’s charter of freedom.

Our republican robe is soiled. Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution. Let us turn slavery from its claims of moral right. Let us return it to the position our fathers gave it. Let us readopt the Declaration of Independence. Let north and south, let all Americans, let all lovers of liberty everywhere join in the great and good work

If we do this, we shall not only have save the Union, but we shall have so saved it, as to make and to keep it forever worthy of the saving.

Political observers recognize in this Peoria speech Lincoln’s absolute mastery of the facts surrounding the national controversy stirred by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Bill.

He emerges as a clear opponent of slavery – but one who recognizes the complexities of the issues, who seeks moderate, not abolitionist, solutions that do not diminish the accepted superior status of white men, and who seeks compromises with the South to hold the Union together.

Finally, and importantly, Lincoln emerges as a western man who can stand toe to toe with Douglas, the powerhouse of the Democratic Party.

A man who someday just might be presidential timber.

Sidebar: Implications Of The Kansas-Nebraska Act

To Douglas and his supporters, the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act appears to offer a rational compromise on the future of slavery, and one that is based on the essence of democracy itself, namely, a popular vote.

As such they hope that it will resolve the kind of North-South antagonism evident in the 1789 Northwest Ordinance debates (drawing the Ohio River boundary), the “fire-bell” alert with the 1820 Missouri Compromise (the 36’30’ demarcation), and the contentious 1850 Compromise.

But this is not to be the case.

One reason being that the absolute legal certainty of a line drawn on a map has now been replaced by the open-ended uncertainty associated with a popular vote.

As a shrewd student of human behavior, Douglas fears this uncertainty all along. But he is left with no choice once the original proposal to extend the 36’30” line to the west coast is rejected, and all of California, even that below the line, is declared Free. His next best option then becomes popular sovereignty.

More surprising to Douglas is the sharply heightened level of intensity — for and against the extension of slavery — that has developed in the North versus the South.

For the powerful Southern planters, expansion has become an economic imperative, the only path to sustained sales growth of their two precious commodities – white cotton and black slaves. If the requisite territory cannot be found by driving further into Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean Islands, then the popular votes from Kansas and the remainder of the west must go in favor of the Slave State outcome.

On the other hand, those in the North are dead set against giving in to this Southern demand, and they now enjoy enough political and economic power to assert their resistance. Their motivations for opposing the expansion of slavery are diverse and often in conflict with each other.

Relatively few Northerners are outright abolitionists, eager to free all slaves and integrate them into American society. But the combined effects of the local Anti-Slavery Societies, the sight of bounty hunters chasing runaways in their streets, popular novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and some amount of contact with assimilated “free blacks” has given rise to a generally increased level of empathy.

Still the majority view in the North and West is much more self-serving. It is typically racist in character, with the conviction that blacks are a different species and certainly inferior to whites. Their harsh treatment as slaves also makes them prone to violent revenge, as evident in the well

publicized uprisings. Furthermore, their presence on plantations in the new Territories represents an economic threat to white settlers competing for land and crop sales — not to mention the “personal humiliation” of honest labor being depreciated by slave labor.

Regardless of these differing motivations, most Northerners tend to agree on one thing – there should be no room in the new Territories for slaves.

Out of these directly opposite North-South convictions will come the collapse of the Union.