Section #21 - A North-South Split in the Democrat Party leads to a Republican Party victory in 1860

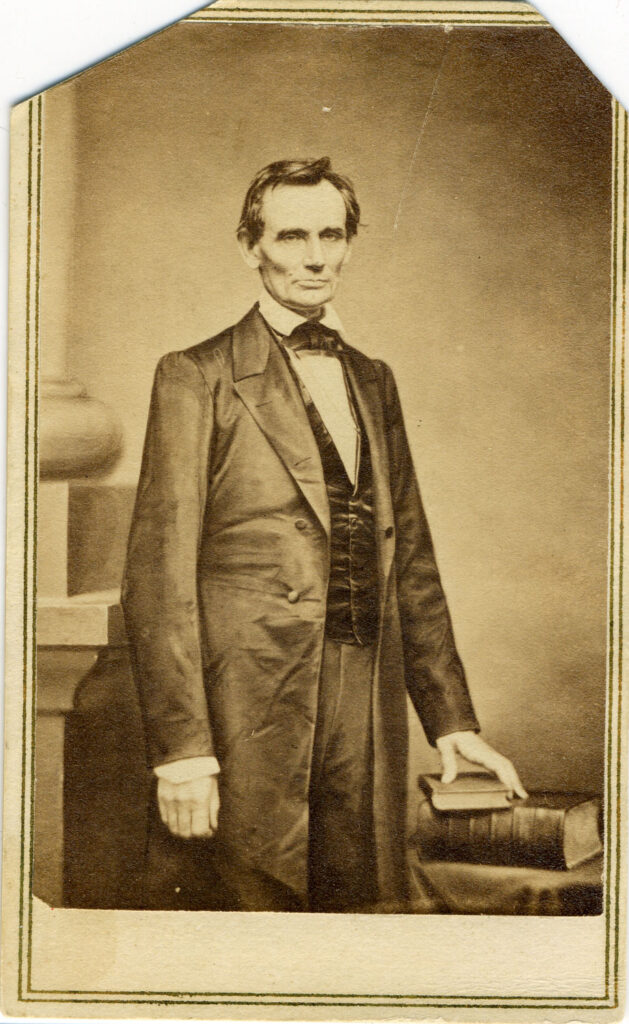

Chapter 249: Abraham Lincoln Delivers His Famous Cooper Union Address In New York

February 27, 1860

Lincoln Seeks A Forum In The East

Eleven weeks before the Republican convention opens, Abraham Lincoln walks on stage in New York City to speak for the first time to an audience of curious, but skeptical easterners.

The event is originally scheduled to take place at the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, home to abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher. But this changes when the Young Men’s Central Republican Union – a “Stop Seward” group including Horace Greeley and W. C. Bryant – invite Lincoln to appear before a much larger audience in lower Manhattan.

The new venue is the Cooper Union and it will lend its name to a pivotal moment in Lincoln’s ascent to becoming a credible candidate for president – the “Cooper Union speech.”

The site is the brainchild of the inventor, businessman and philanthropist, Peter Cooper, whose intent is to provide a free college-level education for “serious students” seeking practical jobs in the modern economy.

In the basement of the Union building is the Great Hall, the largest public auditorium in the city, seating upwards of 1500 people, and home to a lecture circuit connecting students with the world around them. Lincoln’s appearance represents the third in a series on politics and it follows prior visits by Frank Blair of Missouri and Cassius Clay of Kentucky.

Lincoln purchases a new $100 suit for his appearance, and adjusts his text to fit with his non theological setting and audience. The result is a very lengthy speech for him, some 7,000 words, that is divided into three parts — one addressing the Founding Father’s views on slavery, one addressing criticisms leveled at him from the South and one aimed at rallying his Republican supporters.

As usual, audience twitters accompany his initial impression, the gangly 6’4” frame, all arms and legs, large hands and feet, accompanied by the rural Kentucky twang. But soon enough even the doubters are drawn into the sheer power and clarity of his arguments. By the time he is through, his jury of 1500 are on their feet cheering on behalf of “Honest Old Abe.”

Sidebar: History Of The Cooper Union

The site of Lincoln’s speech is the brainchild of Peter Cooper, one of the most prominent men of his generation, whose lifespan runs from 1791 to 1883.

Cooper’s humble origins in New York city include one year of formal education followed by a series of apprenticeships that tap into his God-given talents as an inventor and businessman. Early on he designs a crude washing machine and a chain cable to help move flatboats along difficult canal patches.

He becomes fascinated with the science of glue-making and buys a factory in 1821 which puts him on the road to wealth. Next comes the dawning age of railroads, and Cooper opens up an iron foundry to meet the demand for tracks.

In 1830 comes the invention for which he is most remembered – America’s first steam locomotive, christened the Tom Thumb, which he constructs mainly out of spare parts lying around his foundry. It helps put the Baltimore & Ohio line on the map.

The locomotive also spurs demand for more rails which in turn allows him to expand his iron rolling mill in Trenton, New Jersey that soon employs some 2,000 workers. As the money rolls in, Cooper follows the lead of other tycoons in purchasing and then profiting from real estate in New York city.

Communications get his attention, and in 1855 he co-founds the American Telegraph Company and participates in laying the first transatlantic cable in 1858. He continues to add patents to his name, one being for the popular desert known as Jell-O.

By 1859 he is one of the richest men in the nation, and is already invested in his “reform causes,” which include opposition to slavery, the rights of Native Americans, gender equality and fierce opposition to the “gold standard.” The latter prompts him to run for President in 1885 on his own Greenback Party.

But nearest to Cooper’s heart is his wish to provide people with the kind of education that he failed to experience in his own life. He decides that he wants this to be targeted at adults and he wants it to be free of charge, so everyone has their own shot at the American Dream.

This leads in 1854 to construction of The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, also known at the time as the Cooper Institute. Its charter lies in educating adults of all ages, genders, races and religions in skills required to obtain “useful occupations in life.” It offers an open library, a broad range of courses, and free tuition “for all serious students.” It also boasts the largest public auditorium of its day, the Great Hall, where visiting speakers will include Lincoln, the tribal chief Red Cloud, the suffragette Susan B. Anthony, and the writer Mark Twain, and many other dignitaries.

Peter Cooper’s Institute continues to operate according to its original mission as of 2108.

February 27, 1860

He Proves Founder Support For Federal Control Over Slavery In The Territories

Lincoln begins his address with a remarkable history lesson on the original intent of the “Founding Fathers” in regard to federal authority over controlling slavery in federal territories. He frames the question as follows:

Does the proper division of local from federal authority, or anything in the Constitution, forbid our Federal Government control as to slavery in our Federal Territories?

To answer it, he completes a meticulous examination of the votes cast over time by the “Founders” — the thirty-nine men who signed the 1787 Constitution in Philadelphia – on legislation relevant to the issue. He finds that six such bills exist, dating from 1784, 1787, 1789, 1798, 1804 up to 1819-20, and that a total of 23 of the 39 Founders voted on at least one of them during their legislative careers.

The most telling bill by far is the 1789 Northwest Ordinance, with 17 of the 23 Founders casting a vote, and all approving a federal ban on slavery north of the Ohio River in the territory just won during the Revolutionary War. This bill is signed into law by George Washington himself.

In 1789, by the first Congress which sat under the Constitution, an act was passed to enforce the Ordinance of ’87, including the prohibition of slavery in the Northwestern Territory…George Washington, another of the “thirty-nine,” was then President of the United States, and, as such approved and signed the bill; thus completing its validity as a law, and thus showing that, in his understanding, no line dividing local from federal authority, nor anything in the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government, to control as to slavery in federal territory.

A handful of the original thirty-nine Founders also voted on subsequent bills.

When the Mississippi Territory is organized in 1798, the federal government and Congress prohibited importation of slaves from abroad. Three Founders supported this bill.

In 1798, Congress organized the Territory of Mississippi. In the act of organization, they prohibited the bringing of slaves into the Territory, from any place without the United States, by fine, and giving freedom to slaves so bought. This act passed both branches of Congress without yeas and nays.

Two Founders supported similar federal controls on slavery in 1804 in the Louisiana territory around New Orleans, including one which said:

That no slave should be carried into it, except by the owner, and for his own use as a settler; the penalty in all the cases being a fine upon the violator of the law, and freedom to the slave.

As with the 1789 Northwest Ordinance, the 1820 Missouri Compromise again finds the federal government, by act of Congress, banning slavery north of the 36’30” latitude across all Louisiana Territories. One surviving Founder, Rufus King, favors it, while another, Charles Pinckney, is opposed.

How “Founders” Voted On Bills Involving Federal Controls Over Slavery In Territories

| Year | Bills | Aye | Nay |

| 1784 | 1st Ban on slavery in NW Territory (Articles of Confederation) | 3 | 1 |

| 1787 | 2nd Ban on slavery in NW Territory (Articles of Confederation) | 2 | 0 |

| 1789 | Final ban on slavery in the NW Territory (post Union) | 17 | 0 |

| 1798 | Banning “foreign” slaves in the Mississippi Territory | 3 | 0 |

| 1804 | Regulations on slavery in and around New Orleans | 2 | 0 |

| 1820 | Missouri Compromise banning slavery above 36’30” | 1 | 1 |

Having laid out the facts, Lincoln concludes that the overwhelming majority of the Founders said the federal government has every right to control slavery in the territories.

The sum of the whole is, that of our thirty-nine fathers who framed the original Constitution, twenty-one – a clear majority of the whole – certainly understood that no proper division of local from federal authority, nor any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control slavery in the federal territories; while all the rest probably had the same understanding. Such, unquestionably, was the understanding of our fathers who framed the original Constitution; and the text affirms that they understood the question “better than we.”

He then turns to those who wish to forbid federal control over slavery based on the first ten amendments – specifically the 5th which guarantees the right to “life, liberty and property” and the 10th which grants the states authority over all powers not explicitly handed to the federal body in the Constitution.

He dismisses these pleas saying that the Founders who supported these amendments were the same men who simultaneously passed the 1789 Northwest Ordinance placing federal constrictions on slavery in the territories along the Ohio River.

Now, it so happens that these amendments were framed by the first Congress which sat under the Constitution – the identical Congress which passed the act already mentioned, enforcing the prohibition of slavery in the Northwestern Territory. Not only was it the same Congress, but they were the identical, same individual men who, at the same session, and at the same time within the session, had under consideration, and in progress toward maturity, these Constitutional amendments, and this act prohibiting slavery in all the territory the nation then owned. The Constitutional amendments were introduced before, and passed after the act enforcing the Ordinance of ’87; so that, during the whole pendency of the act to enforce the Ordinance, the Constitutional amendments were also pending.

Given these facts, he asks if it isn’t “a little presumptuous” to assume that the Founders really intended for the theory of the 5th and 10th amendments to overrule the direct actions they took with the Northwest Ordinance!

Is it not a little presumptuous in any one at this day to affirm that the two things which that Congress deliberately framed, and carried to maturity at the same time, are absolutely inconsistent with each other? And does not such affirmation become impudently absurd when coupled with the other affirmation from the same mouth, that those who did the two things, alleged to be inconsistent, understood whether they really were inconsistent better than we – better than he who affirms that they are inconsistent?

This does not, according to Lincoln, mean that Americans are forever bound to “follow implicitly in whatever our fathers did,” but rather that no one should mislead people about the true intent of the Founders on the issue of federal authority.

Now, and here, let me guard a little against being misunderstood. I do not mean to say we are bound to follow implicitly in whatever our fathers did…(and) if any man at this day sincerely believes that a proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbids the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories, he is right to say so…. But he has no right to mislead others, who have less access to history, and less leisure to study it, into the false belief that “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live” were of the same opinion – thus substituting falsehood and deception for truthful evidence and fair argument.

On that note, he ends the opening phase of his address having demonstrated his main point: that the original intent of the Founders was to give the federal government authority over controlling slavery in the territories, and that those who consider this an “overreach” are simply wrong.

Additionally, since slavery is “evil” the Republicans not only have the right to ban it, but also a moral duty.

This is all Republicans ask – all Republicans desire – in relation to slavery. As those fathers marked it, so let it be again marked, as an evil not to be extended, but to be tolerated and protected only because of and so far as its actual presence among us makes that toleration and protection a necessity.

By this point in his talk, those in the audience who initially questioned his gangly appearance and Kentucky accent are being drawn in by the clarity and power of his intellect.

He precedes next to address the men of the South.

He Counters The Southern Attacks On Republicans

The remainder of the Cooper Union speech is political in nature. It begins with a plea to the South to stop the name-calling directed at all Republicans and engage in a debate over the principles at stake.

And now, if they would listen – as I suppose they will not – I would address a few words to the Southern people….You consider yourselves a reasonable and a just people… Still, when you speak of us Republicans, you do so only to denounce us as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws…. If we do repel you by any wrong principle or practice… bring forward your charges and specifications, and then be patient long enough to hear us deny or justify…Meet us, then, on the question of whether our principle, put in practice, would wrong your section…. Do you accept the challenge?

Given the facts Lincoln has already laid out, a failure to discuss the principles implies that the South is willing to ignore or condemn what the Founders intended on federal control of slavery.

No! Then you really believe that the principle which “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live” thought so clearly right as to adopt it, and indorse it again and again, upon their official oaths, is in fact so clearly wrong as to demand your condemnation without a moment’s consideration.

He again returns to Washington’s actions and commentary on the 1789 Northwest Ordinance a proof of the principles the Republicans espouse.

Washington…as President of the United States, approved and signed an act of Congress, enforcing the prohibition of slavery in the Northwestern Territory, which act embodied the policy of the Government upon that subject up to and at the very moment he penned that warning; and about one year after he penned it, he wrote LaFayette that he considered that prohibition a wise measure, expressing in the same connection his hope that we should at some time have a confederacy of free States…. Could Washington himself speak, would he cast the blame of that sectionalism upon us, who sustain his policy, or upon you who repudiate it? We respect that warning of Washington, and we commend it to you, together with his example pointing to the right application of it.

While the South seems ready to reject the Founder’s and the Republican’s proposals on slavery, they have been unable to arrive at a consensus plan of their own.

Some of you are for reviving the foreign slave trade; some for a Congressional Slave Code for the Territories; some for Congress forbidding the Territories to prohibit Slavery within their limits; some for maintaining Slavery in the Territories through the judiciary; some for the “gur-reat pur-rinciple” that “if one man would enslave another, no third man should object,” fantastically called “Popular Sovereignty;” but never a man among you is in favor of federal prohibition of slavery in federal territories, according to the practice of “our fathers who framed the Government under which we live.” Not one of all your various plans can show a precedent or an advocate in the century within which our Government originated. Consider, then, whether your claim of conservatism for yourselves, and your charge or destructiveness against us, are based on the most clear and stable foundations.

Lincoln proceeds to a series of Southern accusations made against the Republican Party, beginning with the contention that it supported John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry.

We deny it; and what is your proof? Harper’s Ferry! John Brown!! John Brown was no Republican; and you have failed to implicate a single Republican in his Harper’s Ferry enterprise. If any member of our party is guilty in that matter, you know it or you do not know it. If you do know it, you are inexcusable for not designating the man and proving the fact. If you do not know it, you are inexcusable for asserting it, and especially for persisting in the assertion after you have tried and failed to make the proof. You need to be told that persisting in a charge which one does not know to be true, is simply malicious slander.

He knocks down the charge that Republicans have caused the slave uprisings.

Slave insurrections are no more common now than they were before the Republican party was organized. What induced the Southampton insurrection, twenty-eight years ago, in which, at least three times as many lives were lost as at Harper’s Ferry? You can scarcely stretch your very elastic fancy to the conclusion that Southampton was “got up by Black Republicanism.” In the present state of things in the United States, I do not think a general, or even a very extensive slave insurrection is possible. The indispensable concert of action cannot be attained.

He quotes Thomas Jefferson’s comments on slavery and his wish to see Virginia rid itself of “the evil” over time.

In the language of Mr. Jefferson, uttered many years ago, “It is still in our power to direct the process of emancipation, and deportation, peaceably, and in such slow degrees, as that the evil will wear off insensibly; and their places be, pari passu, filled up by free white laborers. If, on the contrary, it is left to force itself on, human nature must shudder at the prospect held up.”

Mr. Jefferson did not mean to say, nor do I, that the power of emancipation is in the Federal Government. He spoke of Virginia; and, as to the power of emancipation, I speak of the slaveholding States only. The Federal Government, however, as we insist, has the power of restraining the extension of the institution – the power to insure that a slave insurrection shall never occur on any American soil which is now free from slavery.

In seeking to destroy the Republican Party, the South will not be able to end “the feeling against slavery in the nation” expressed by over a million and a half voters.

There is a judgment and a feeling against slavery in this nation, which cast at least a million and a half of votes. You cannot destroy that judgment and feeling – that sentiment – by breaking up the political organization which rallies around it. You can scarcely scatter and disperse an army which has been formed into order in the face of your heaviest fire; but if you could, how much would you gain by forcing the sentiment which created it out of the peaceful channel of the ballot-box, into some other channel? What would that other channel probably be? Would the number of John Browns be lessened or enlarged by the operation?

In threatening to “rule or ruin” the Union,” Lincoln says the South continues to claim “rights” regarding slavery that are simply not contained in the Constitution.

But you will break up the Union rather than submit to a denial of your Constitutional rights. That has a somewhat reckless sound; but it would be palliated, if not fully justified, were we proposing, by the mere force of numbers, to deprive you of some right, plainly written down in the Constitution. But we are proposing no such thing.

When you make these declarations, you have a specific and well-understood allusion to an assumed Constitutional right of yours, to take slaves into the federal territories, and to hold them there as property. But no such right is specifically written in the Constitution. That instrument is literally silent about any such right. We, on the contrary, deny that such a right has any existence in the Constitution, even by implication. Your purpose, then, plainly stated, is that you will destroy the Government, unless you be allowed to construe and enforce the Constitution as you please, on all points in dispute between you and us. You will rule or ruin in all events.

He next goes head-on against the notion that the Dred Scott decision is definitively in favor of the South’s position. His argument here mirrors his prior views, namely that the justice’s opinions were divided and contradictory, and that neither the words “slavery nor property” even appear in the Constitution. Furthermore, the absence of the word “slavery” shows that the majority of Founders were embarrassed to acknowledge the thought of “property in men” in their defining document.

Perhaps you will say the Supreme Court has decided the disputed Constitutional question in your favor. Not quite so. ,,,The Court have decided the question for you in a sort of way…I mean it was made in a divided Court, by a bare majority of the Judges, and they not quite agreeing with one another in the reasons for making it; that it is so made as that its avowed supporters disagree with one another about its meaning, and that it was mainly based upon a mistaken statement of fact – the statement in the opinion that “the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.”

An inspection of the Constitution will show that the right of property in a slave is not “distinctly and expressly affirmed” in it….Neither the word “slave” nor “slavery” is to be found in the Constitution, nor the word “property” even… Also, it would be open to show, by contemporaneous history, that this mode of alluding to slaves and slavery, instead of speaking of them, was employed on purpose to exclude from the Constitution the idea that there could be property in man.

Lincoln ends his “words to the South” by dismissing the idea that the Republicans will be responsible for destroying the Union if he is elected President. He compares this to blaming a victim of a robbery for his own death for failing to turn over his money upon demand.

But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, “Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!”

To be sure, what the robber demanded of me – my money – was my own; and I had a clear right to keep it; but it was no more my own than my vote is my own; and the threat of death to me, to extort my money, and the threat of destruction to the Union, to extort my vote, can scarcely be distinguished in principle.

With that said, Lincoln turns to closing remarks for the Republicans in the audience.

He Calls On Republicans To Stand Firm Against The Expansion Of Slavery

Lincoln begins the third and closing part of his speech with a plea to Republicans to do everything within reason to accommodate Southern concerns in order to hold the union together.

A few words now to Republicans. It is exceedingly desirable that all parts of this great Confederacy shall be at peace, and in harmony, one with another. Let us Republicans do our part to have it so. Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper. Even though the southern people will not so much as listen to us, let us calmly consider their demands, and yield to them if, in our deliberate view of our duty, we possibly can. Judging by all they say and do, and by the subject and nature of their controversy with us, let us determine, if we can, what will satisfy them.

But that has not been an easy task so far.

The question recurs, what will satisfy them? Simply this: We must not only let them alone, but we must somehow, convince them that we do let them alone. (This) is no easy task. We have been so trying to convince them from the very beginning of our organization, but with no success. In all our platforms and speeches we have constantly protested our purpose to let them alone; but this has had no tendency to convince them.

The only answer seems to be for the Republicans to affirm out loud that slavery is “right,” in fact “a social blessing” that deserves “full national recognition.”

This, and this only: cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly – done in acts as well as in words. Silence will not be tolerated – we must place ourselves avowedly with them. Senator Douglas’ new sedition law must be enacted and enforced, suppressing all declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. We must pull down our Free State constitutions. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of opposition to slavery, before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us.

Holding, as they do, that slavery is morally right, and socially elevating, they cannot cease to demand a full national recognition of it, as a legal right, and a social blessing…. If slavery is right, all words, acts, laws, and constitutions against it, are themselves wrong, and should be silenced, and swept away.

Lincoln asks his audience if they are willing to surrender their belief that slavery is wrong to satisfy the South.

Can we cast our votes with their view, and against our own? In view of our moral, social, and political responsibilities, can we do this? Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is, because that much is due to the necessity arising from its actual presence in the nation; but can we, while our votes will prevent it, allow it to spread into the National Territories, and to overrun us here in these Free States?

His answer is a ringing call to action for all Republicans to have faith in the rightness of their convictions, to “stand by our duty,” and to reaffirm the clear intent of the Founders to stop the spread of slavery.

If our sense of duty forbids this, then let us stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively. Let us be diverted by none of those sophistical contrivances wherewith we are so industriously plied and belabored – contrivances such as groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong, vain as the search for a man who should be neither a living man nor a dead man – such as a policy of “don’t care” on a question about which all true men do care – such as Union appeals beseeching true Union men to yield to Disunionists, reversing the divine rule, and calling, not the sinners, but the righteous to repentance – such as invocations to Washington, imploring men to unsay what Washington said, and undo what Washington did.

Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves. LET US HAVE FAITH THAT RIGHT MAKES MIGHT, AND IN THAT FAITH, LET US, TO THE END, DARE TO DO OUR DUTY AS WE UNDERSTAND IT.

By the end of the speech, Lincoln has transformed himself in the east from an unknow Midwestern oddity into a credible candidate for the presidency.

The political editor Horace Greeley sums up this transformation in his New York Tribune coverage:

No man ever made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience.