Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 96: Abolitionists Enter Politics After An Internal Schism

1839

Garrison Alienates Some Supporters By Further Radicalizing His Agenda

While the Whigs and Democrats are forming up their plans for the 1840 elections, the issue of “political action” is dividing what was heretofore a united Abolitionist front.

From the beginning, the Boston-based abolitionists – Lundy, Garrison, Phillips, Mott, Whittier and Douglass – have refused to turn their cause into a political movement, which they fear would lead to compromising and softening their attacks on slavery.

By 1839, however, this perspective is being challenged by leaders like James Birney, Theodor Weld, the Tappan brothers and Gerrit Smith, who represent the New York and Ohio wings of the movement.

This division breaks into the open at a January 1839 meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

Garrison is once again at his shrillest here over a full range of American social norms and institutions.

He moves beyond calls for immediate emancipation and black assimilation to open support for racial intermarriage, feminine equality and suffrage, and passive resistance to laws he rejects. He castigates the clergy and all political parties, and urges others to join him in no longer voting in elections.

Much of this is beyond the pale for the more moderate New York and Ohio faction. Instead of drawing additional mainstream Americans into their cause, they see Garrison’s increasingly radical messages as driving people away and destroying the one practical path to their end – gathering enough popular support to pass abolition laws in Washington.

From 1839 forward, the Abolitionists will find themselves split into two wings.

Lloyd Garrison’s Boston-based followers will try to stay out of politics, and rely strictly on what he terms “moral suasion” to free the slaves — his Liberator, other written material, the itinerant public lecturers and various public societies.

The New York and Ohio-based wing will jump into the political arena, first by forming their own abolitionist party, and later by backing anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats. Later on, a few will also support violent means to achieve their ends.

1839 – forward

James Birney And Gerrit Smith Embrace A Political Path To Abolition

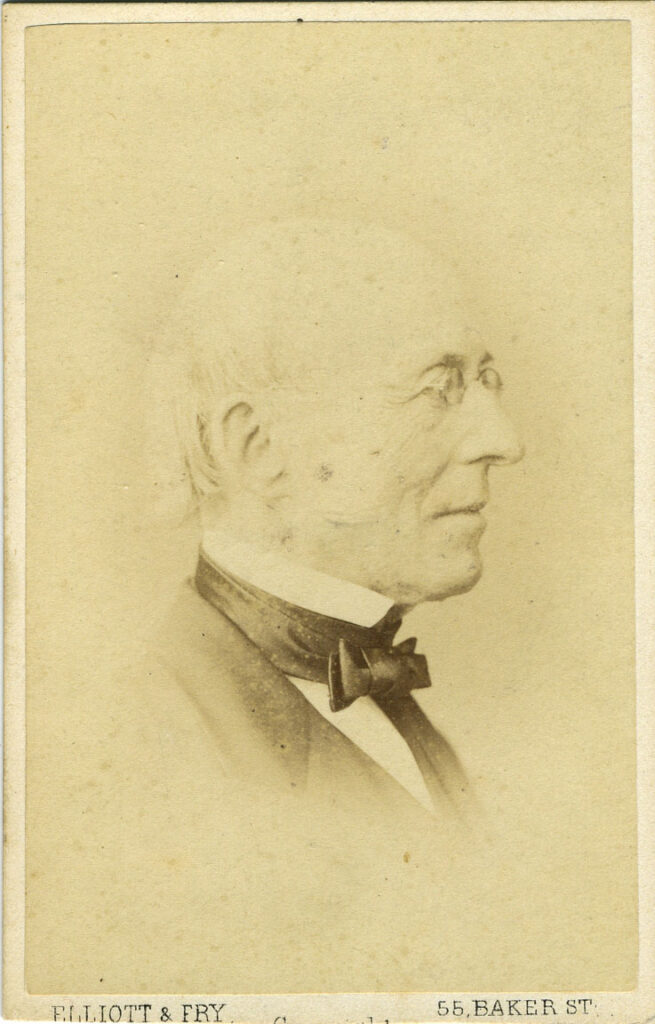

Two men in particular will lead the Abolitionists into the political arena – James Birney, an ex-slave owner living in Ohio, and Gerrit Smith, the philanthropic reformer from upstate New York.

Birney grows up in Danville, Kentucky, where slavery is taken for granted. His father owns slaves, and he is given several as a wedding present when he marries the aristocratic Agatha McDowell. His education at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) leads on to a very successful legal practice in Danville. He is a powerful debater, and enters the political arena in 1816 when elected to the state legislature.

In 1819 he picks up and moves to Alabama to try his hand at running a cotton plantation that includes some 43 slaves. Once there he helps write the constitution that leads to statehood in 1819, and eventually serves in the state’s first legislature. His political stance is staunchly pro-Clay and anti-Andrew Jackson.

On the surface, Birney’s future as a Southern planter and politician seems fixed by age 28, in 1820.

But then his world comes apart. He suffers crop failures which, combined with gambling debts and lavish spending, lead on to financial ruin. He loses a child and becomes an alcoholic. Finally he decides to sell off most of his slaves to pay debts, and to move to Huntsville to try to pick up the pieces as a lawyer.

This works. He joins the Presbyterian Church in 1826, which restores his bearings. He serves as a States Attorney, then is elected Mayor of the city in 1829. But much of his energy focuses on a personal quest –exploring his past involvement with slavery. His final conclusion shocks fellow Southerners:

Slavery is a sin before God. Men have no more right to enact slavery than they have to enact murder.

Birney now follows through on his new convictions. He frees and pays off his remaining slaves, actively works on behalf of the American Colonization Society, and formally connects with the Abolitionist movement through Theodore Weld.

After moving back to Danville in 1835 Birney leaps into the center of the controversy by publishing an abolitionist paper, The Philanthropist. When local mobs threaten his safety, he moves north to the free state of Ohio, only to see his paper become a precipitating cause of the race riots that again disrupt Cincinnati in 1836. The attacks on Birney and the riots bring another prominent Ohio figure, Salmon P. Chase, into the Abolitionist cause.

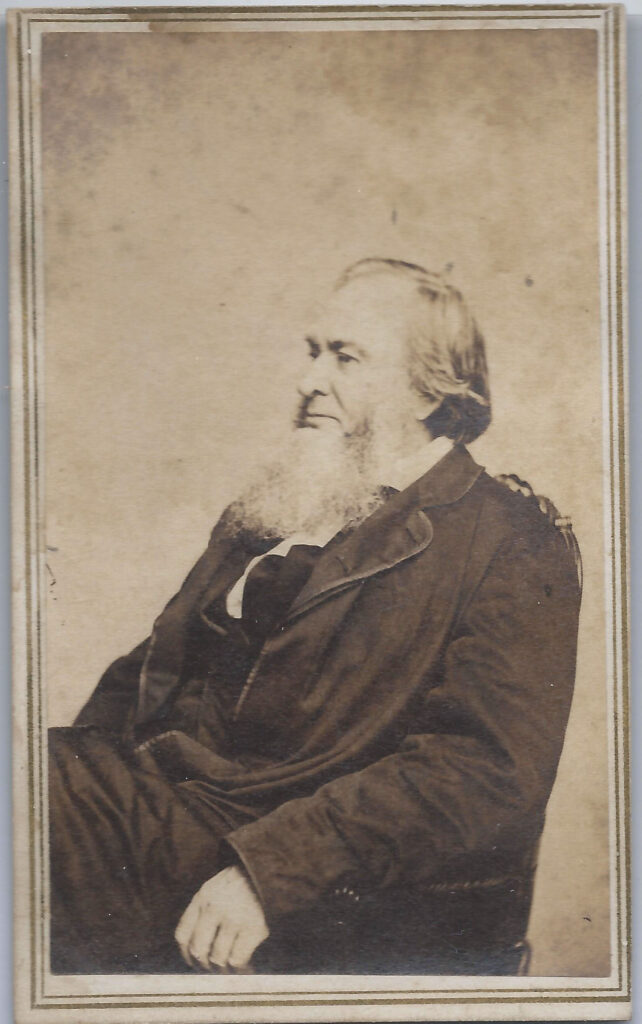

These two will soon be joined by Gerrit Smith, a figure well known for supporting experiments in social re-engineering.

Smith is born in Utica, N.Y. into fabulous wealth, accumulated by his father, Peter, who is a long-term partner in John Jacob Astor’s fur trading empire. After graduating from Hamilton College, he takes over management of the estate and grows it handsomely.

Like many other reformers of his era, Smith’s life is re-shaped by the Reverend Charles Finney. In 1835 he attends revivalist services led by Finney in Utica, New York. From then on, he becomes a life-long supporter of the preacher, and a major financial contributor to his Oberlin College.

Under Finney’s influence, Smith defines his agenda as a philanthropist. He begins with temperance, then branches out into abolition, land and prison reform, women’s suffrage, even vegetarianism and Irish independence.

In 1839, Smith’s focus lies on working with Birney and Chase to move the abolition cause into the political arena where rhetoric can be translated into laws and action.

November 13, 1839

Abolitionists Found The Liberty Party

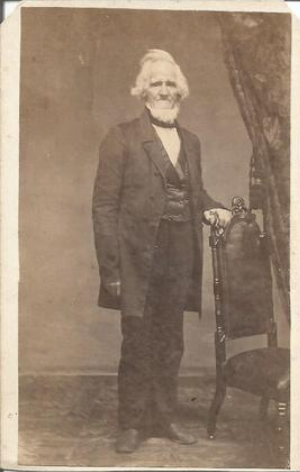

On November 13, 1839, a coalition including Birney, Chase, Smith, Arthur Tappan and New York Judge William Jay, meet in Warsaw, New York, and agree on a charter for “The Liberty Party.”

Resolved, That, in our judgment, every consideration of duty and expediency which ought to control the action of Christian freemen requires of the Abolitionists of the United States to organize a distinct and independent political party, embracing all the necessary means for nominating candidates for office and sustaining them by public suffrage.

The new party holds it first convention at City Hall in Albany, N.Y., on November 13, 1839, with 121 delegates from six states present. James Birney is nominated to run for President, with Thomas Earle, a noted lawyer and journalist from Pennsylvania, joining the ticket as Vice President.