Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

Chapter 72: Abolitionists Are Met By Attacks In The North And South

As of 1830

The Vast Majority Of Northerners Oppose Freeing The Slaves

The general public in the North is drawn into the slavery issues by a series of events that touch their lives in one way or another: the 1820 controversy over the admission of Missouri; the week-long Second Awakening revivalist meetings held in their towns; news of the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia; and the infrequent, but vocal calls to end slavery appearing in abolitionist newspapers and town hall meetings.

The vast majority have already made up their minds, based on generations of stereotypical prejudices.

Those least sympathetic to those enslaved regard blacks as a different and inferior species, incapable of advancement, and ready to seek violent revenge against whites if given the chance.

A second group, much smaller, exhibits a mixture of guilt and empathy toward the slaves. They feel it was wrong to bring the Africans to America in the first place and that, while they are by no means “equal” to whites, their continued enslavement is inconsistent with the nation’s commitment to freedom for all.

Even so they cannot imagine simply freeing them. The result they see would be a mass exodus to the North followed not by assimilation, but by increases in poverty, crime, and violence, lower wages for white workers, and even intermarriages and racial pollution.

For both groups, the demand is for “containment” – segregating and controlling local blacks in the North and opposing any actions that would allow them to spread beyond the South.

In addition, they also share a growing resentment toward the Southern “Slavocracy” for failing to resolve an issue that is dividing the nation.

Finally, a third group of Northern whites, even more limited in number, convert their empathy with the slaves into a willingness to voice their opposition. Some join an Anti-Slavery Chapter, while others become “radical Abolitionists.”

Like Lloyd Garrison they will devote their lives to fighting for immediate emancipation, free migration of blacks, assimilation into white society and full citizenship.

For their efforts they will be met by public hostility and threats to their lives.

1831-1834

Race Riots Break Out In The North

The level of antagonism toward blacks and abolitionists in the North is such that even minor perceived offense can turn into violence.

This is the case back in October 1824 in Providence, Rhode Island, when a black man fails to exhibit the proper subservience by failing to move off a sidewalk in the presence of oncoming whites. This sparks a race riot — with gangs of incensed whites roaming the segregated Hardscrabble section of town, beating blacks and destroying upwards of 20 homes.

A similar incident is repeated there in 1831, this time requiring the local militia to stop the attacks.

Then comes the Chatham Street race riot in New York City in the summer of 1834. It springs from an incident involving Lewis Tappan and the Reverend Samuel Cox.

The impetus is a simple act of kindness on Sunday, June 12, at the Laight Street Presbyterian Church in the notorious “Five Points” district of New York City. When Tappan arrives at the service he encounters a black minister, Reverend Samuel Cornish, and invites him to sit alongside him in his pew. This causes an immediate stir among other white parishioners, which is then compounded by words from the pulpit.

The Reverend Samuel H. Cox observes the visible hostility toward both Cornish and Tappan and offers a sermon on the need for good will, especially between different races. After all, he intones, it is well known that the people of the Holy Land – including Jesus himself – were typically dark-skinned.

A hostile press immediately seizes upon Cox’s words to fan the flames of anti-black feelings. Unless radicals like Tappen and Cox can be silenced, whites can expect to have Negroes invading their places of worship and ministers asserting that “Jesus was black.” Tensions build from there.

Attempts to hold an abolitionist meeting at the Chatham Street Chapel two blocks south of the Five Points intersection are broken up by angry white mobs on three occasions around the 4th of July.

On July 10 they damage the homes of both Tappan and Cox, and then on the 11th hundreds of whites systematically go about destroying the homes, churches, businesses and welfare centers across the entire black enclave.

The message here is clear – there is no place in New York City for either abolition or assimilation.

July 6, 1835

The South Tries To Ban All Abolitionist Literature

Southern whites are even more distressed by the Abolitionist movement than those in the North.

Of particular concern in the 1830’s is the growing number of anti-slavery publications that are filtering into southern cities through the mail. They are regarded as propaganda efforts by the North, meant to stir up the slaves and prompt further violence akin to Nat Turner’s rampage in Virginia in 1831.

On July 6, 1835, a white mob decides to put an end to this threat.

They do so by burning abolitionist tracts outside the Charleston post office, and demanding that Charles Huger, the local postmaster, refuse to accept any more of these materials when they are delivered.

This incident represents the first attempt by the South to officially “gag” the anti-slavery opposition.

Huger contacts Amos Kendall, a Dartmouth man, close friend of Jackson’s and Postmaster General, about ordering an end to disseminating anti-slavery materials. Kendall responds by saying he has no legal authority to do so – although he agrees to encourage local offices to do just that, saying:

We owe an obligation to the laws, but a higher one to the communities in which we live.

For many Southerners this is not good enough.

Georgia passes a law in 1835 to impose the death penalty on anyone who publishes material that could provoke a slave uprising.

Governor George McDuffie, one of the early secessionist “fire-eaters” from South Carolina, proclaims that:

The laws of every community should punish this species of interference by death without benefit of clergy.

The intensity of these reactions will soon carry the suppression attempts into the political arena in Washington.

October 21, 1835

A White Mob Threatens To Lynch Lloyd Garrison

With the American Anti-Slavery Society up and running, Lloyd Garrison turns his inflammatory rhetoric against what he considers another form of anti-black racism.

On June 1, 1832, he publishes his only book, Thoughts of African Colonization, a direct assault on those whites who wish to free the slaves — but only if they are then put on ships and sent back to Liberia.

Colonization, according to Garrison, is nothing more than a ploy by which certain white leaders can appear to embrace “anti slavery” idealism, while still holding on to their “Negro-phobia” beliefs.

It is one thing to wish to abolish slavery; quite another to support “assimilation” and black citizenship. And that is exactly what Garrison demands:

All God’s creatures can live in harmony together, of this I am sure.

In May of 1833 a 27 year old Garrison sails to England to meet William Wilberforce and other abolition leaders, and to update them on progress in America. On July 12, in an address to a large British crowd at Exeter Hall, he lashes out against his homeland:

America falsifies every profession of its creed in its support for slavery.

When the American Colonization Society reports on Garrison’s speech, opponents quickly brand him a traitor to his country – and violent mobs greet him dockside in NYC when he returns home on October 2.

Resistance to abolition also builds in Boston. On September 10, 1835, a burning cross signed by “Judge Lynch” appears on Garrison’s front lawn. Six weeks later, on October 21, he is kidnapped by a mob in the city on his way to a lecture event and a hangman’s noose is put around his neck. Only a last second rescue by the Mayor of Boston saves his life.

The Tappan brothers, Lucretia Mott and other visible leaders also experience attacks over time.

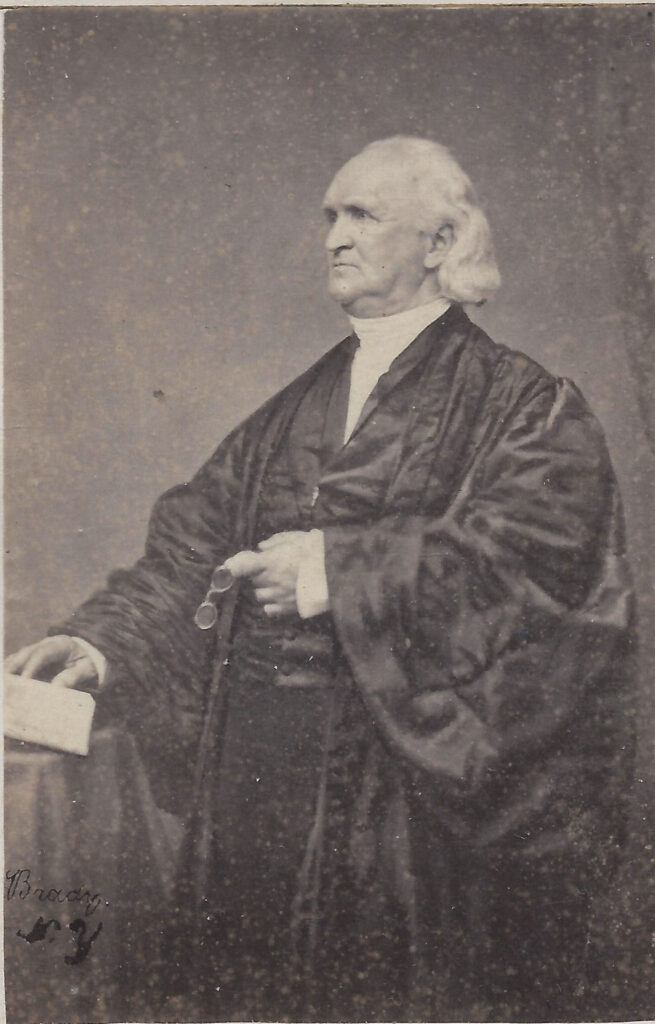

Even the gentle Unitarian minister William Channing chides the Abolitionists in December 1835 for their “showy, noisy societies” that run the risk of fomenting slave rebellions and jeopardizing peace with the Southern states. Characteristically Garrison responds by calling Channing an “equivocator.”

Ironically these attacks draw new supporters to the cause, including James G. Birney and Gerrit Smith — who will eventually steer many Abolitionists to search of a political solution.

July 1836

James Birney Joins The Cause And Is Attacked In Cincinnati

For many years the city of Cincinnati has been a hotbed of racial tension, and the appearance in January 1836 of an anti-slavery newspaper, The Philanthropist, published by James G. Birney, is greeted by open hostility.

Going all the way back to 1804, one year after Ohio’s admission to the Union, the legislature passes a series of “black codes” making it clear that Negroes are not welcome within the state’s border. They are not banned outright – as will be the case with most other new states to the west – but are required to post an onerous $500 bond to insure their residence and “proper behavior.” Despite the stricture, many slaves, especially from Kentucky, flock across the Ohio River, seeking relative freedom in towns like Cincinnati.

Birney’s new paper is regarded as an invitation for even more blacks to take up residence.

In April 1836, Irish mobs terrorize black neighborhoods in the city, apparently over competition for low wage jobs. The Governor resorts to martial law to end the uproar. But not for long.

The entire month of July is marked by white mob violence against blacks and against Birney. On July 12 and again on the 30th, Birney’s office is ransacked and his presses are broken up and thrown into the river.

Posters offering a $100 “bounty” for the “fugitive from justice, James Birney” – a black man masquerading in white skin –appear across Cincinnati, and the city council tries to ban further issues.

Some white, however, see these attempts to gag vocal opponents of slavery as an infringement on freedom of speech and decide to speak out in support of Birney.

1836

Harriet Beecher Stowe And Salmon Chase Commit

The 1836 race riot in particular appalls two prominent residents of Cincinnati.

One is Harriet Beecher Stowe, daughter of influential Presbyterian Minister, Lyman Beecher, who records her fright at seeing “negroes being hunted like wild beasts” during the riots.

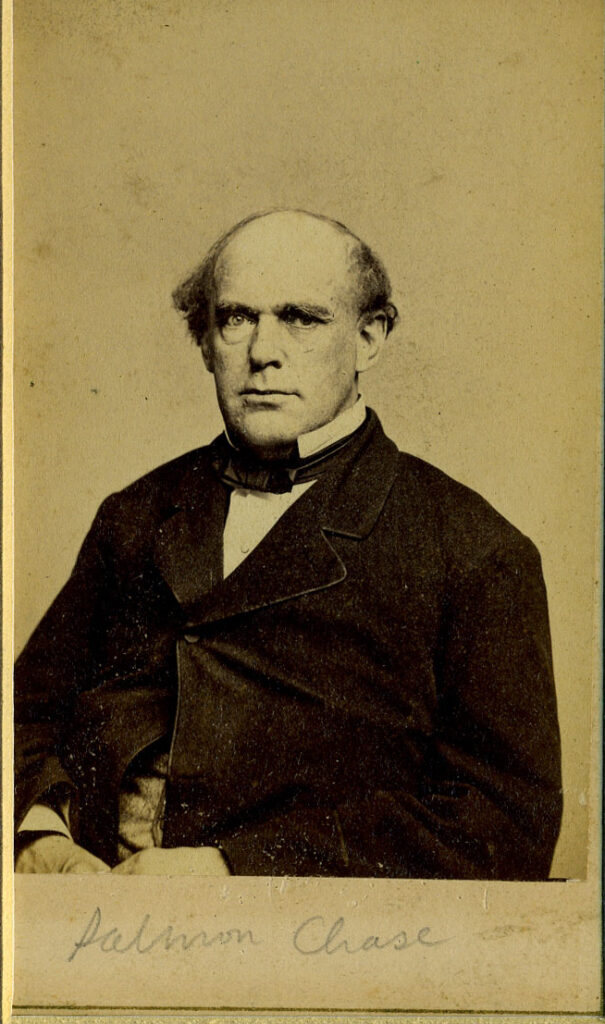

The other, Salmon P. Chase, a highly regarded city lawyer, witnesses his sister fleeing to her house for safety, and commits himself to re-establishing civil order.

Both will play pivotal roles over the next twenty-five years in the abolitionist movement.