Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

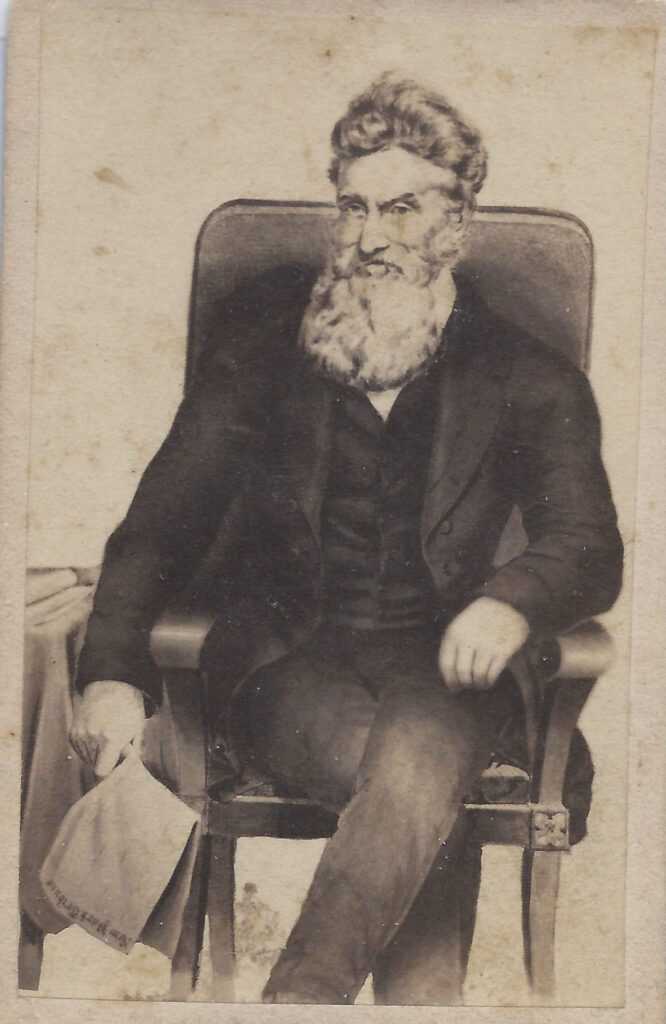

Chapter 163: Abolitionist John Brown Advances His Plan To Lead A Slave Rebellion In The South

1837 to 1850

Brown’s Opposition To Slavery Grows Since The 1837 Murder Of Elijah Lovejoy

The Fugitive Slave Act also reenergizes the anti-slavery zealot, John Brown.

Thirteen years have passed since his public pledge in his Ohio church to destroy slavery, in response to the murder of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois:

Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!

At that moment Brown is 37 years old, and has already experienced a transient and challenging life. His study for the ministry in Connecticut is cut short for want of funds; a tannery he opens in New Richmond, Pennsylvania becomes the first of his many business failures; he remarries after his wife dies from childbirth in 1832; then retreats to Franklin Mills, Ohio with his five surviving children to start afresh.

Like his father, Owen, he becomes a “station” master on the Underground Railroad, and intermingles daily with the freedmen living in nearby Hudson. He hires many to work at a new tannery he sets up along the Cuyahoga River, and encourages others to do likewise. His affinity for blacks strike many as extreme, and when he begins ushering freedmen to pews at his church, he is temporarily expelled.

But in no way do these personal setbacks undermine his 1837 oath to end slavery.

By the summer of 1839 he is already formulating a plan to recruit bands of Southern slaves and lead them in violent attacks against Southern plantations – along the lines of Nat Turner’s uprising in 1831.

Before he can act, however, his own life again unwinds. His Franklin Mills tannery folds during the recession which follows Andrew Jackson’s monetary reforms, and on September 28, 1842, a federal court declares him officially bankrupt. When he refuses to vacate his foreclosed land, he is arrested and jailed. A year later, three of his sons and one daughter die suddenly from dysentery.

To revive his economic prospects, he becomes an expert at breeding animals, and forms a partnership in 1843 with a Simon Perkins of Akron, to raise sheep and to promote sales of the fine wool they provide. Since manufacturing of woolens is centered in New England, he picks up his second wife and seven children and moves to Springfield, Massachusetts.

The town has a sizable population of blacks, and is already known as a hotbed of anti-slavery zeal. He joins the Sanford Street Free Church, run by freedmen, and again hires many to work in his warehouse. Among them is one Thomas. Thomas, who recalls Brown at age forty-three:

When he was here he was smooth-faced and had black, heavy hair brushed straight up from his forehead. He always dressed in plain browns, something like a Quaker. He wasn’t tall, nor anything of a giant, as some represent, and he wasn’t at all fierce or crazy looking. He was medium in height and he was quiet and agreeable to talk with. He was a gentleman and a Christian.

At the Sanford Street Church Brown also attends lectures by the newly declared abolitionists, including both Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass.

In November of 1847, after dining with Douglass, he hauls out map of the Appalachian Mountain region and describes his plan to lead a slave revolt.

These mountains were placed here to aid the emancipation of your race…I know these mountains well and could take a body of men into them and keep them there in spite of all the efforts of Virginia to drive me out.

Upon hearing this vision, Douglass records his impression of Brown:

Though a white gentleman, he is in sympathy with the black man and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.

Sidebar: John Brown’s Twenty Children

John Brown will father twenty children between 1820 and 1854. Seven are with his first wife, Dianthe, who comes from a Puritan family. In later years he remembers her as:

A neat, industrious and economical girl; of excellent character; earnest piety; and good common sense…who maintained a most powerful and good influence over me.

Dianthe dies in 1832, three days after delivering a stillborn son – leaving Brown on his own to raise his five remaining children.

To help out, he hires a housekeeper, a sixteen year old woman, Mary Day. The two quickly fall in love and are married in June 1833, ten months after Dianthe’s death. The first of their thirteen children is born in 1834.

In total, only eight of John Brown’s twenty children will outlive their parents. Two die as unnamed infants, one stillborn, the other surviving for seventeen days.

Seven die before they are ten, with four of these all struck down in the same month by dysentery.

The remaining three – sons Frederick #2, Watson and Oliver – are killed while participating in Brown’s later rampages in Kansas and Harpers Ferry.

The Fates Of John Brown’s Twenty Children

| By Dianthe Lusk | Born | Where Destiny | |

| John, Jr. | 6/21/20 | OH | Grows up and marries – dies 1895 |

| Jason | 1/19/23 | OH | Grows up and marries – dies 1912 |

| Owen | 11/4/24 | OH | Grows up and dies 1889 |

| Frederick #1 | 1/9/27 | Pa | Dies at four in 1831 |

| Ruth | 1/18/29 | Pa | Grows up and marries – dies in 1904 |

| Frederick #2 | 12/21/30 | Pa | Murdered 8/30/56 at Osawatomie, KS |

| Unnamed son | 8/7/32 | Pa | Stillborn, Dianthe then dies 8/10/32 |

| By Mary Ann Day | |||

| Sarah #1 | 5/11/34 | Pa | Dies at nine – September 1843 |

| Watson | 10/7/35 | Pa | Dies 10/19/59 of wounds at Harpers Ferry |

| Salmon | 10/2/36 | OH | Grows up and marries – dies 1919 |

| Charles | 11//3/37 | OH | Dies at five – September 1843 |

| Oliver | 3/9/39 | OH | Killed at Harpers Ferry on 10/17/59 |

| Peter | 12/7/40 | OH | Died at two – September 1843 |

| Austin | 9/14/42 | OH | Died at one – September 1843 |

| Ann | 12/23/43 | OH | Grows up – dies 1926 |

| Amelia | 6/22/45 | OH | Died at one in 1846 |

| Sarah #2 | 9/11/46 | OH | Grows up – dies 1916 |

| Ellen #1 | 5/20/48 | Mass | Died at one in 1849 |

| Unnamed son | 4/26/52 | OH | Died at 17 days in 1852 |

| Ellen #2 | 9/25/54 | OH | Grows up and marries – dies 1916 |

Brown exhibits a particular fondness for three names – Frederick, Sarah and Ellen – and recycles these in honor of children who die young. Mary Day Brown outlives her husband by a quarter of a century, dying in 1884 in California, where she migrates during the Civil War.

May 1849

Brown Connects With Abolitionist Leader Gerrit Smith

The combination of John Brown’s interests in the wool industry and his outspoken opposition to slavery puts him in touch with a wide range of merchants and other anti-slavery men across New England.

One of these is the philanthropist turned abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, who by now has distanced himself from Lloyd Garrison, and is seeking more aggressive strategies to end slavery, especially through political action.

In 1848, Brown learns that Smith is offering land grants on property he owns in the Adirondack region of upstate New York, the purpose being to create a utopian community of whites and blacks, living and working side by side, exemplifying a social order for America once the slaves are liberated.

Smith’s vision immediately appeals to Brown, who buys 244 acres (at $1 apiece) in New Elba, New York, near Lake Placid – and in May 1849 he sends his family to live there while he remains behind in Springfield to oversee his business.

To succeed financially, he must find buyers for his inventory of fine wool, and to do so, he personally travels to England in 1849. The trip, however, proves a dismal failure and leads to the collapse of his partnership with Simon Perkins, who bears the brunt of the monetary losses.

As usual, Brown is undeterred by this latest setback, remarking that he was “nerved to face any difficulty while God continues me such a partner.”

Amidst a host of follow-up court trials with creditors, he never loses focus on his crusade against slavery.

He is further refining his plan to rampage through Virginia in 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Act becomes law.

In January, 1851, he responds by organizing a group of some 45 freedmen in Springfield to resist what he considers the latest act of Southern aggression.

He names this band the “League of Gileadites.”

January 1851

Brown’s “League Of Gileadites” Organized To Attack All Slave-Catchers

John Brown will win lasting fame as the first white man to take up arms to liberate American slaves.

But his commitment to violent action is in the tradition of a host of black predecessors – including Toussaint Louverture’s 1791 revolution against France along with the black uprising by Gabriel Prosser in 1800, Charles Deslondes in 1811, Denmark Vesey in 1822 and Nat Turner in 1831.

Free Blacks cite justifications for violence as a last resort.

In 1829 when David Walker publishes his famous Appeal, first pleading with whites to behave as Christians, and then encouraging violent resistance if nothing changes:

If you can only get courage into the blacks, I do declare it, that one good black man can put to death six white men; and I give it as a fact, let twelve black men get well armed for battle, and they will kill and put to flight fifty whites. The reason is, the blacks, once you get them started, they glory in death.

The whites have had us under them for more than three centuries, murdering, and treating us like brutes; and, as Mr. Jefferson wisely said, they have never found us out– they – not know, indeed, that there is an unconquerable disposition in the breasts of the blacks, which, when it is fully awakened and put in motion, will be subdued, only with the destruction of the animal existence.

The verbal drumbeat continues in 1842 with the black firebrand, Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, telling his followers to “commence the work of death” if need be:

…Then go to your lordly enslavers and tell them plainly, that you are determined to be free. Appeal to their sense of justice, and tell them that they have no more right to oppress you, than you have to enslave them… If they then commence the work of death, they, and not you, will be responsible for the consequences. You had better all die immediately, than live slaves and entail your wretchedness upon your posterity. If you would be free in this generation, here is your only hope. However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood. If you must bleed, let it all come at once—rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.

Brown’s formation of the League of Gileadites picks up on these earlier initiatives.

It represents his first attempt to organize a band of blacks and personally lead them in armed resistance – in this case against bounty hunters who may arrive in Springfield. His marching orders in this regard are unequivocal:

Do not delay one moment after you are ready; you will lose all resolution if you do. Let the first blow be the signal for all to engage; and when engaged do not do your work by halves, but make clean work with your enemies….

This call to action in 1851 will be repeated in the years ahead, first during the Kansas crisis of 1856 and then again in 1859 at Harpers Ferry.

Sidebar: The Old Testament Gileadites

For a man who begins each day by gathering his family together to read Bible scripture, it is no surprise that Brown christens his Springfield recruits the “League Of Gileadites.”

The story of the Gileadites is found in the Old Testament Book of Judges.

It tells of the warrior king Gideon, chosen by God to free the people of Israel and return them to the path of righteousness.

Gideon assembles a mighty army of some twenty thousand men at Mt. Gilead, east of the Jordan River, and prepares to assault his Bedouin enemy, the Midianites. Before he can strike, however, the Lord orders him to winnow his forces to the bravest of the brave, the 300 men comprising the “League of Gileadites.”

When the time for battle arrives, the Gileadites are ordered to advance to the sound of their ram’s horn trumpets. The result, according to scripture, is a cascade so loud and frightening that the Midianites flee the field without a fight.

This tale of the power of God’s righteousness combined with man’s courage is memorialized in a 1750 hymn composed by the Methodist, Charles Wesley.

Blow ye the trumpet, blow

The gladly solemn sound:

Let all the nations know,

To earth’s remotest bound,

The year of jubilee is come;

Return, ye ransom’d sinners, home.

The hymn becomes one of John Brown’s favorites, and an inspiration throughout his life.