Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 44: A White Abolitionist Movement Gets Under Way

1619 Forward

Moral Opposition To Slavery Is Muted Up To The 1800’s

The institution of chattel slavery goes largely unchallenged on moral grounds up to the early 1800’s.

Indeed there are some exceptions, but these are few and far between.

Some Early Anti-Slavery Protests

| Date | Action |

| 1688 | The Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery |

| 1743 | Quaker John Woolman’s anti-slavery pamphlets and reform tours |

| 1747 | Minister Jonathan Mayhew’s crusade |

| 1773 | Dr. Benjamin Rush’s assertion that blacks are not intellectually inferior to whites |

| 1774 | Methodist John Wesley’s missions to end slavery |

| 1775 | Ben Franklin’s “Pennsylvania Society For Relief Of Negroes Unlawfully Held In Bondage” |

| 1787 | Attacks by Gouvernor Morris and Luther Martin at the Constitutional Convention |

| 1785 | Rush and Franklin found the New York Manumission Society |

Once Northerners find that the international slave trade is no longer profitable, the vast majority focus on segregating and controlling the few blacks left in their own neighborhoods and ensuring that those enslaved in the South stay there.

Southerners by then have discovered that their “peculiar institution” is the basis for their ongoing economic prosperity, and are ready to defend it to the death.

So the only opposition to slavery seems to come from those who would oppose its future geographical spread – based on prejudice and greed — not from any drive to end the practice entirely based on moral grounds.

1815

Three Quakers Found A Small Scale Abolitionist Movement

The notion of emancipating all slaves in America has its roots in three New England Quakers, Elias Hicks, Benjamin Lundy and Lucretia Mott.

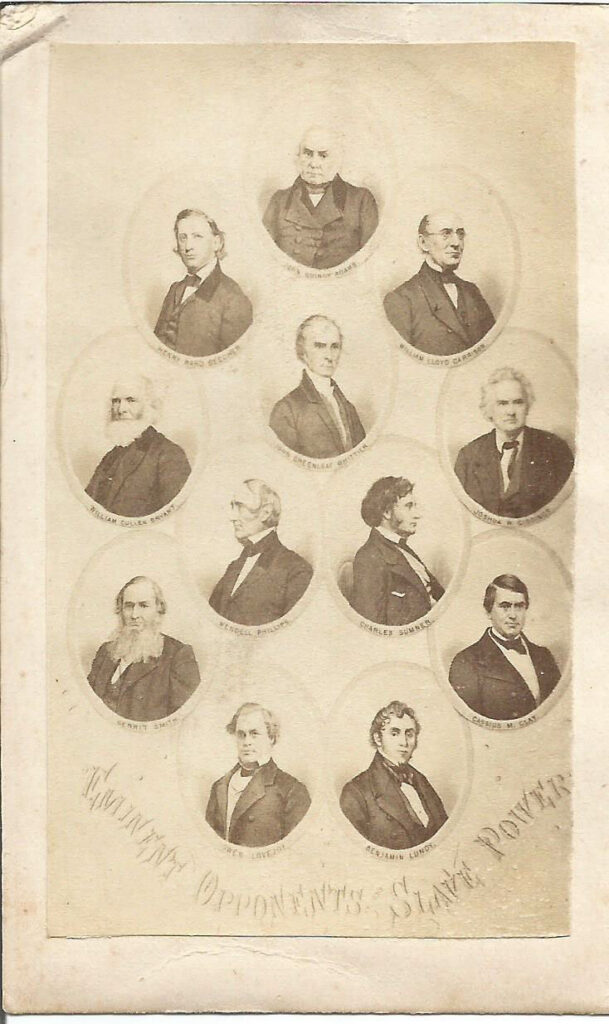

Including Ben Lundy (lower right)

Hicks is a New Yorker, born in 1748, who becomes a carpenter and farmer by trade. He joins the Assembly of Friends at age 21 and is quickly recognized by his congregation for the spiritual insights he voices during prayer meetings. As such he is chosen as a “recording minister,” and becomes an itinerant preacher.

From the beginning he converts his beliefs into action. He frees his family slaves in 1778, sets up a Charity Society for Africans in 1794, and by 1811 advocates an economic boycott of all goods – especially cotton and sugar – produced by slaves. By his words and deeds, Hicks influences not only Ben Lundy but also Lucretia Mott.v

Lundy is born in 1789 and raised on a farm in New Jersey. At 19 years he moves to Wheeling, in western Virginia, in order to apprentice as a saddler. While learning the craft, he is exposed to, and horrified by, the slave trade that is active in the town. Like many other converts to abolition, he is particularly bothered by the sight of chained “coffles” of slaves in pens, awaiting shipment south. He later reflects on this experience:

It grieved my heart, and the iron (to oppose it) entered my soul.

Lundy’s saddling business leads to economic success, and, in 1815, he moves west to Mt. Pleasant, Ohio, where he sets up shop, marries, begin a family and commences on a quiet and prosperous life.

His Quaker conscience, however, convinces him that his purpose in life lies in a personal crusade against the evils of slavery he witnessed years ago. So he sells his business and sets out on his mission.

In 1815, with help from other Friends, Lundy founds The Union Humane Society – the first such group in his time to publicly speak up on behalf of emancipation.

He begins to tour the countryside and deliver public lectures attacking the evils of slavery. He also writes articles for a Friend’s newspaper, and, when the owner dies in 1821, he becomes the hands-on publisher. He names the paper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation.

Over the next eighteen years, Benjamin Lundy will devotes all of his resources and strength to eradicating slavery in America, and enlisting important new converts in his cause.

In 1825 he escorts freed slaves to Haiti, then returns home to learn that his wife has died and his five children have been placed in a foster home. He decides to leave them there, and free himself totally to carry on his quest, earning this tribute from the poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, on his death in 1839:

It was“(Lundy’s) lot to struggle, for years almost alone, a solitary voice crying in the wilderness, and, amidst all, faithful to his one great purpose, the emancipation of the slaves.

Lundy will also be remembered for one of his final acts, in 1829, when he strikes up a conversation in Boston with a 23 year named Garrison – an iron-willed Baptist and neophyte reformer — whom Lundy encourages to join the crusade.

Soon enough Garrison will become the face of the abolitionist movement across the nation. The third founding member of the early abolitionist movement is the charismatic Lucretia Mott.

She is born Lucretia Coffin in 1793 in Nantucket, Massachusetts. At age thirteen her parents send her off to Nine Partners Quaker Boarding School, where she is educated and where she begins her career as a teacher, alongside her future husband, James Mott.

She marries, becomes a teacher, then a biblical scholar and finally a lay minister in 1821, at the age of 28 years.

Like her counterparts, she rebels against the rote traditions of her church and calls for:

Practical godliness over ceremonial religion.

The search for “truth,” according to Mott, begins by looking inside oneself and connecting with the potential perfection, “the inner light,” that lies within.

Then comes action. The duty of the awakened is to go forth and reform the world’s ills – something she will pursue all the way to her death in 1880.

By 1815, Mott, along with Lundy, will influence the Quaker General Assembly to speak out on behalf of abolition, declaring that the practice of buying and selling slaves is “inconsistent with the Gospels.”

“Mother Mott” will later take Garrison under her wing as his chief spiritual advisor.

1818

A Virginia Attacks Slavery

While public criticism of slavery is almost unheard of in the South, one exception is George Bourne, a Presbyterian minister in Virginia.

He begins a life-long abolitionist crusade in 1818 by issuing his screed, The Book And Slavery Irreconcilable, in which he declares that the Bible cites “man-stealing” as a sin.

His sermons against slavery are soon met by a firestorm of resistance, and he is cast off from the ministry, first by his local congregation and then by the General Assembly.

Like all of the outspoken abolitionists of the era, Bourne risks his safety on a daily basis, and he soon abandons his home in Virginia to move north.

He lives on until 1845, becoming a newspaper editor in New York City and a leading national voice for immediate abolition.

George Bourne’s nominal heirs in this regard will include the martyred editor, Elijah Lovejoy, and his friends, Lloyd Garrison and the philanthropist, Lewis Tappan.