Section #12 - Southerners are alarmed by an apparent Northern wish to ban all blacks from the new West

Chapter 144: A Proposed Ban On Slavery In DC Intensifies Sectional Anger In The House

December 18- 21, 1848

Joshua Giddings Bill To Ban Slave Trading In The District Of Columbia Passes In The House

Even before Taylor is inaugurated, the slavery issue flares up again in Congress.

This time the instigator is not David Wilmot, but rather Joshua Giddings of Ohio, who, for a full decade, has stood alongside his mentor, John Quincy Adams, as lone crusaders on behalf of abolition.

Giddings grows up on a modest farm in Ashtabula, Ohio, in the northeast corner of the state known as the Western Reserve. This land, formerly owned by Connecticut, is dominated by New England emigrants, and Giddings soon absorbs their Puritan values. He is a strapping youth, 6’2” tall, athletic and brimming with self-confidence. He serves at age 16 in the War of 1812, then returns to work the farm and continue his self-education. He is a natural scholar and soon apprentices himself to Elisha Whittlesey of nearby Canfield to prepare for the bar, which he passes in 1821. His joint practice with fellow Ohioan, Benjamin Wade, leads to fame and fortune, prior to the crash of 1837, which nearly wipes away his wealth.

At that point, friends push him into politics and, in 1838; he is elected to the House, to succeed his teacher and friend, Whittlesey.

Soon both Giddings and Wade are drawn into their shared opposition to slavery, first through lectures delivered by Theodor Dwight Weld, the disciple of Reverend Charles Finney, and later through Giddings daughter, Lura Maria, a dedicated Garrisonian. Together the two law partners form an Anti-Slavery Society chapter, before Giddings heads off to Washington.

Once there, he keeps a diary, with 1838-39 entries bearing witness to the slave trade in DC, and to the frustrations, he faces in trying to end it.

• This day a coffle of about sixty slaves, male and female, passed through the streets of Washington, chained together on their way south. A being in the shape of a man was on horseback, with a large whip in his hand, with which he occasionally chastised those who, through fatigue or insolence, were tardy in their movements. This was done in daylight, in public view.

• I say that Northern men will not consent to the continuance of our national councils where their ears are assailed while coming to the Capitol by the voice of the auctioneer publicly proclaiming the sale of humans, of intelligent beings…I am asked now to contribute from the funds of the people thus abused to the improvements of this city…I protest against this. I shall be opposed to all appropriations in this District not necessary for the convenience of government. I take my stand here.

• It is amusing and astonishing to see the views entertained by most of the members on the subject of abolition. At the South, that is designed to create a general rebellion among the slaves, and have them cut their master’s throats. At the North they have no definite idea of the meaning …and appear afraid to come out and declare their sentiments.

• I have come to the honest conclusion that our northern friends are in fact afraid of these southern bullies.…I think we have no northern man who dares boldly and fearlessly to declare his abhorrence of slavery and the slave trade. This kind of fear I have never experienced, nor shall I submit to it now. For that purpose I have drawn up a resolution calling for information as to the slave trade in the District of Columbia…Friends advise me not to present it on two accounts: first it will enrage the southern members; second it will injure me at home. But I have determined to risk both; for I would rather lose my election at home than to suffer the insolence of these Southerners.

By 1848, after a decade of frustration in the House, Giddings senses a tide beginning to shift his way.

On December 18, 1848, he tests this by offering a stature to abolish slavery in the District – arguing that DC is federal land and thus not subject to Maryland’s state law sanctioning the institution. But this bill is defeated by a 106-79 margin,

A subsequent option, initiated by Abraham Lincoln, seeks DC abolition in exchange for compensation for freed slaves, plus a guarantee to seize and return all runaways. It is tabled without a vote.

Giddings, however, has a fallback position. On December 21, he proposes another bill, this time to at least ban slave trading in the District.

Its passage by a margin of 98-88 sounds another alarm for Southerners. If the House is willing to pass restrictions on slavery on “federally controlled” land in DC, might it not apply the same principle to the new Mexican Cession “territories” out west? Might it even go so far as to prohibit slavery before the “territories” write their own constitutions and apply for statehood?

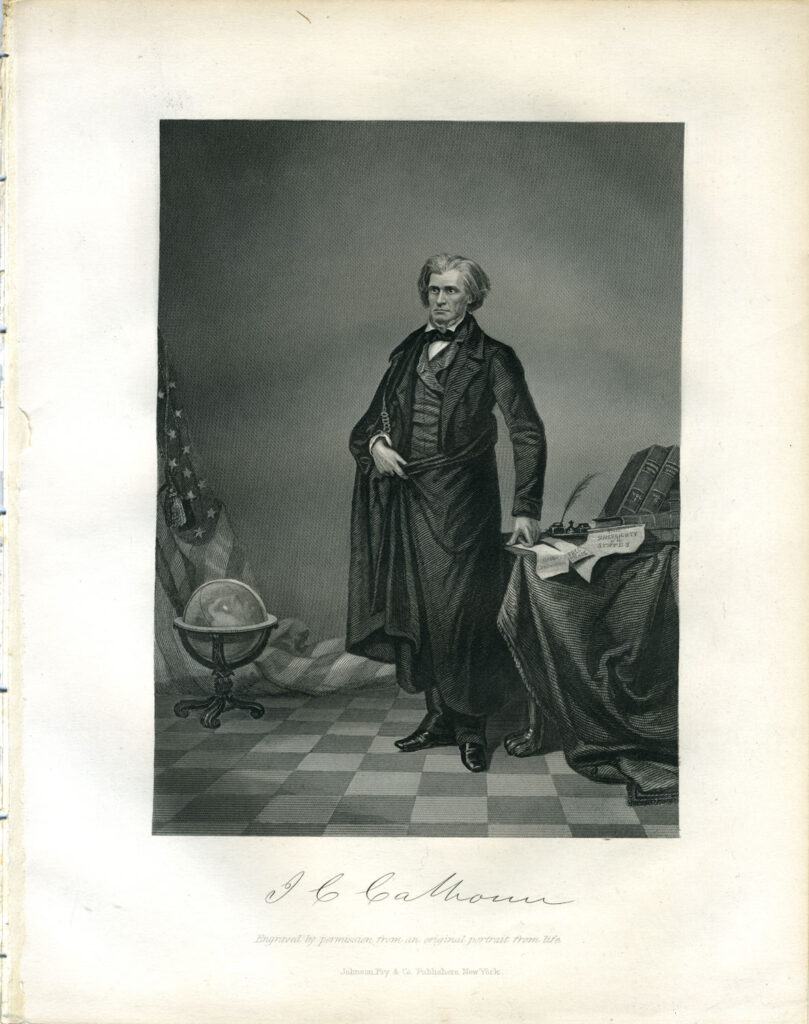

Senator John Calhoun of South Carolina seems to think so.

December 22, 1848

Calhoun Tries To Unify Southern Support For Slavery

Unlike many Southerners, sixty-six year old Senator John Calhoun is not lulled into complacency by Zachary Taylor’s planter credentials. He fears for the General’s political naiveté, and suspects that he will soon fall under the influence of Northern Whigs, especially anti-slavery New Yorkers such as Governor William Seward and party boss Thurlow Weed.

Calhoun’s strategy is to go on the offensive to protect the South, before it is too late.

His immediate fear in December 1848 is that a Northerndominated Congress will move quickly to outlaw slavery across the entire Mexican Cession before Southern planters can gain a toehold in the region.

To try to forestall this “free soil” fait d’accompli, Calhoun convinces 69 of the 121 southern members of Congress to convene on December 22, 1848, for the purpose of constructing a unified sectional platform on the slavery issues.

He tells this caucus that unless the South acts swiftly and with one voice, both California and New Mexico will become “free states.” This, in turn, will tip the current 15:15 balance in the Senate in favor of the North, and open a path to end the expansion of slavery and crush the South’s economic future.

The caucus agrees to set up a “Committee of Fifteen” to further discuss the issues and draft a statement, which Calhoun will write himself.

January 15, 1849

Calhoun’s “Address To The Southern Delegates In Congress” Fails To Stir Rebellion

The Committee statement is presented by Calhoun to a collection of 90 Southern congressmen and senators at a meeting held in the Senate chamber on January 15, 1849.

But instead of unity, the result is chaos.

Leading Southern Whigs such as Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens of Georgia oppose its “threatening” tone. Others are so offended by the acrimonious debate it triggers that they exit the hall. Those who remain finally agree to meet again to debate Calhoun’s proposal versus a toned-down option.

On January 22 they reconvene, and Calhoun’s version is adopted. But it is a hollow victory. In the end, only 48 of the 121 southern members go on to actually sign the petition, with a mere two Whigs among them.

Southern Politician’s Support For Calhoun’s Petition

| Sign On | Do Not Sign | Total | |

| Democrats | 46 | 27 | 73 |

| Whigs | 2 | 46 | 48 |

| Total | 48 | 73 | 121 |

Despite this tepid support, Calhoun goes ahead and publishes his “Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress to Their Constituents.” His goal is clearly to scare the region into action.

Thus he argues that the North’s true intent is to raise all blacks to equality with whites, to hand them the vote, and to thereby abolish slavery.

They intend to vest the free blacks and slaves with the right to vote on the question of emancipation in this District. But when once raised to an equality, they would become the fast political associates of the North, acting and voting with them on all questions, and by this political union between them, holding the white race at the South in complete subjection.

Like Cassandra foretelling the fall of Troy, Calhoun goes on to warn that failure to act will destroy the Southern way of life and turn the land into:

A permanent abode of disorder, anarchy, misery and wretchedness.

Only by banding together can this fate be avoided.

The first and indispensable step, without which nothing can be done, and with which everything may be, is to be united among yourselves, on this great and most vital question. Until then, the North will not believe that you are in earnest in opposition to their encroachments, and they will continue to follow, one after another, until the work of abolition is finished.

If political opposition fails, Calhoun invokes the specter of war:

Nothing (then) would remain for you but to stand up immovable in defense of rights involving your all – your property, prosperity, equality, liberty, and safety. As the assailed, you would stand justified by all laws, human and divine, in repelling a blow so dangerous, without looking to consequences, and to resort to all means necessary for that purpose.

For the moment, however, this dire warning falls on deaf ears.

The Southern Whigs, having finally won the White House, have no interest in abandoning Taylor in favor of Calhoun. The Democrats simply assume that Taylor, the slaveholder, will protect their interests in the end.

Toombs regards the outcome as a triumph, and reports it to Taylor’s main political confidante, the Whig Unionist, Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky:

We have completely foiled Calhoun in his miserable attempt to form a southern party.