Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Chapter 9: A New Constitution is Approved For The United States

May 14, 1776

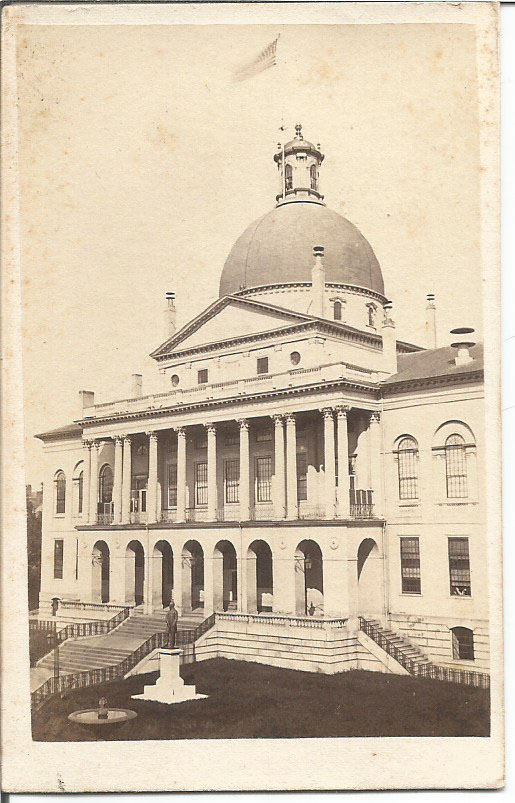

The Constitutional Convention Convenes

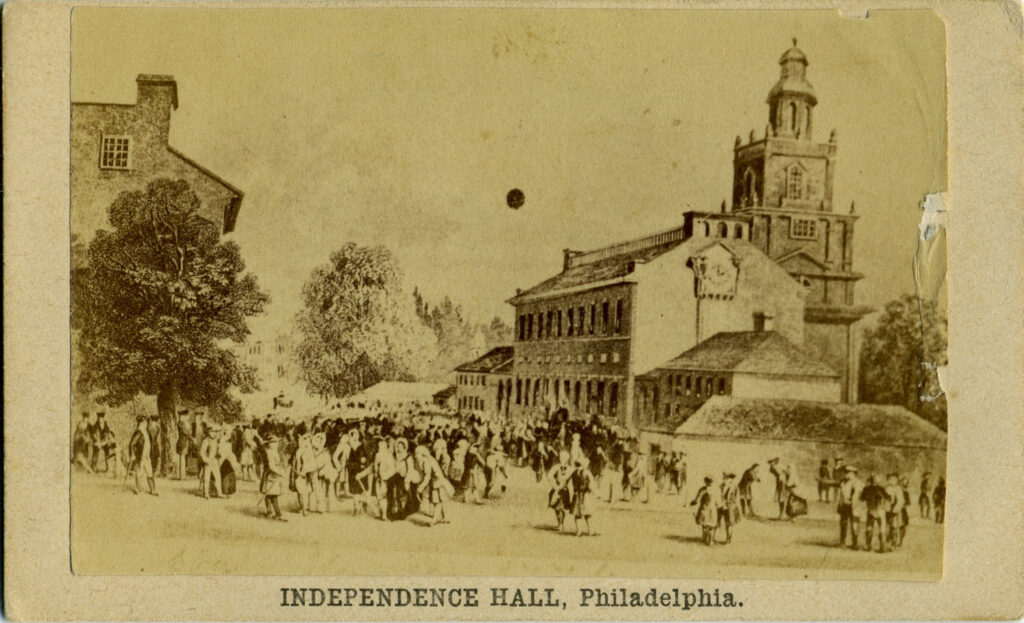

The Constitutional Convention at Independence Hall in Philadelphia is in session for four months, from May 14 to September 17, 1787 – with spotty attendance the norm throughout. Rhode Island boycotts the entire event, infuriating Washington. Delegates from New Hampshire appear nine weeks late. Only two states, Virginia and Pennsylvania, are present on the first day, and a quorum of seven isn’t achieved until May 25. Of the 74 men chosen to attend, only 55 ever show up, and less than 30 stay from start to finish.

The 55 delegates who do attend are consistently white males, well-educated, wealthy, and have been active in politics. All have participated in the Revolution – 41 having attended the Continental Congress and 29 having served in the Continental Army. Their careers are diverse: 35 are lawyers (but not all practicing), 14 oversee plantations and slaves, 13 are merchants, 11 are financiers, 7 are land speculators, 4 are doctors, 2 are small farmers, another 2 scientists, and one is a college president. Just over half are slave owners.

At the state level, attendance is well-balanced. Six states are smaller (populations under 300,000) and six are larger. Six are from the North and six are from the mid-to-deep South. Six have very sizable slave populations and six do not.

Composition Of Delegates Who Actually Attend

| North (25) | # Delegates | 1790 Pop (000) | High % Slaves |

| Penn | 8 | 434 | No |

| Mass | 4 | 379 | No |

| NY | 3 | 340 | No |

| Conn | 3 | 238 | No |

| NJ | 5 | 184 | No |

| NH | 2 | 142 | No |

| RI | 0 | 69 | No |

| Border (10) | |||

| Md | 5 | 320 | Yes |

| Delaware | 5 | 59 | Yes |

| South (20) | |||

| Va | 7 | 748 | Yes |

| NC | 5 | 394 | Yes |

| SC | 4 | 249 | Yes |

| Ga | 4 | 82 | Yes |

Several prominent figures from prior enclaves are missing from this one, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams are serving as ambassadors to Paris and London respectively, and leading Anti-Federalists such as Sam Adams, John Hancock, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry are also absent.

The work of the convention is thus done by a relatively small number of men with, fair to say, a tilt toward strengthening the hand of the Federal Government vis a vis the individual States. The work is hard and it is contentious. So much so that the delegates agree to operate entirely in closed session – for fear that the acrimony involved in the debates will tear the country apart rather than strengthen its unity.

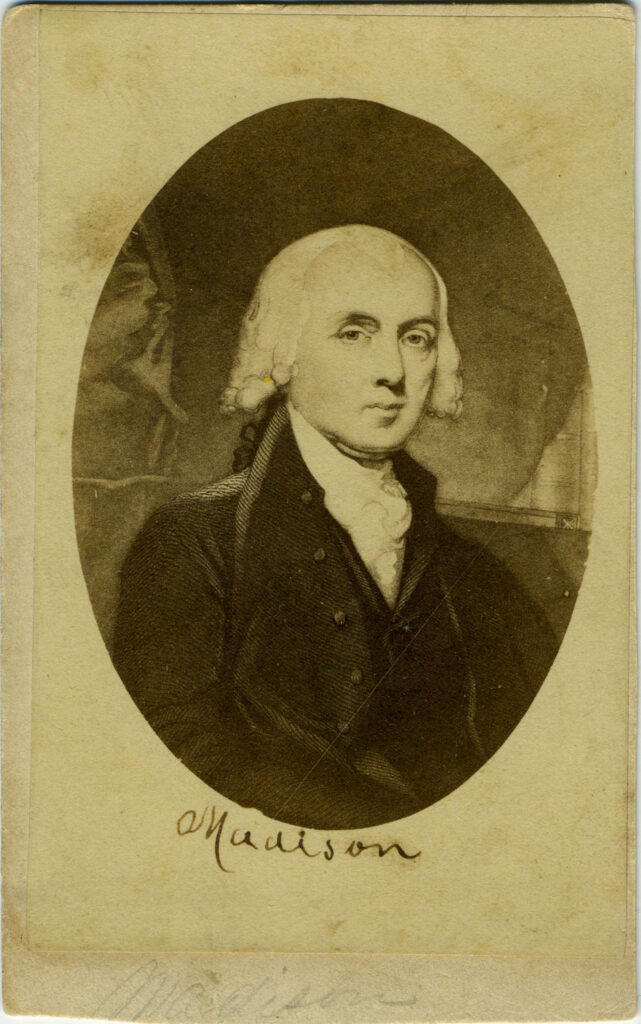

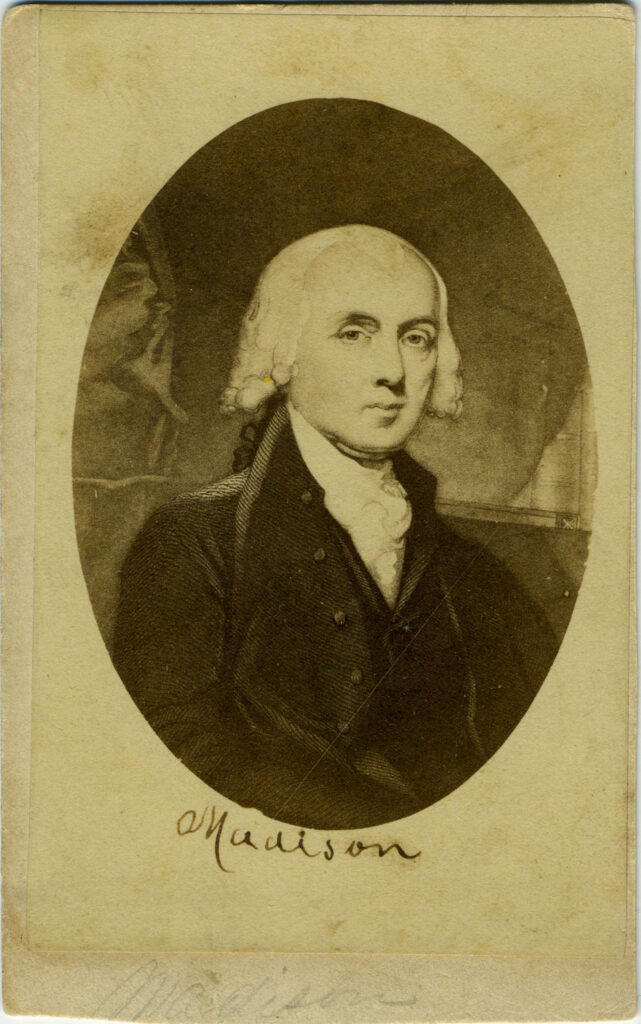

The “record” of each session is compiled by the unofficial Secretary, James Madison, whose “Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787” will not be made public until 1840.

Decisions reached by the body are often very close calls, based on horse-trading compromises. Some issues are so divisive they are simply set aside for future generations to resolve. Then comes the need for each State to vote on the agreements. This process is nip and tuck and drags on for over three years, with Rhode Island’s approval in May 1790 and Vermont, as 14th state, agreeing in January 1791.

In hindsight the fact that the convention successfully institutes a new government is remarkable.

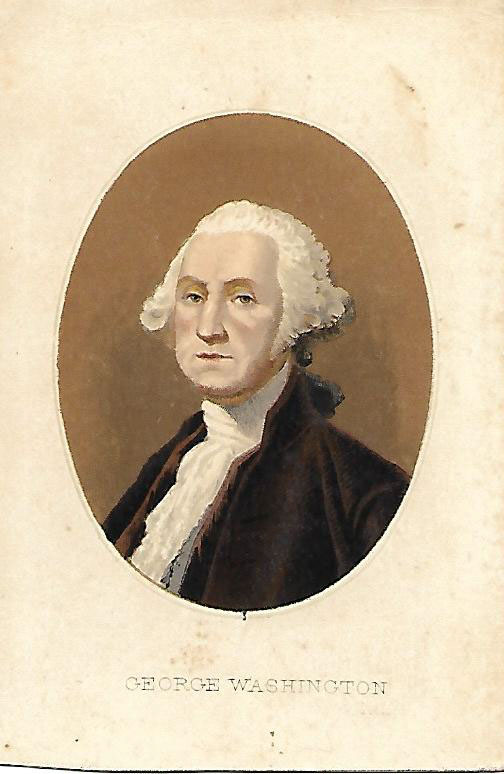

The lion’s share of the credit for this outcome belongs to George Washington, who comes out of retirement to attend, who only speaks out on issues once during the session, but whose reputation for placing the needs of the nation above his own personal preferences sets the standard for the delegates.

Benjamin Franklin, now 81 years old, supports Washington throughout the process. Franklin is instrumental in defining the vision and values of the new nation, negotiating disputes among the delegates at the Convention, and codifying the agreements in plain-spoken language. Of all the founding fathers, Franklin alone signs all four documents integral to the Revolution: the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance With France, the Treaty of Paris ending the war, and the U.S. Constitution.

In a roomful of 55 strong-willed, often self-interested and hot-tempered delegates, Washington and Franklin act as the two wise men who eventually steer the ship of state into safe harbor.

May 14 – September 17, 1787

A Host Of Complicated Issues Faces The Assembled Delegates

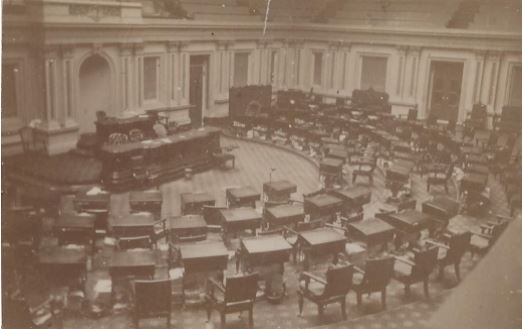

Procedural matters mark the start of the convention. The nation’s “Superintendent of Finance,” Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, nominates Washington to serve as presiding officer. After John Rutledge, the powerful leader of the South Carolina delegation, seconds the nomination, Washington is affirmed unanimously. He will sit at the front of the hall on a raised dais, in an armchair backed with an elaborate carving of a rising sun. He wears his old military uniform, and is addressed throughout as “General Washington.”

Next comes a gentlemen’s pledge to conduct the proceedings in secrecy, doors and windows shut, despite the stifling summer heat — with some 600 pages of notes captured by Madison, as record keeper.

From there the business of the convention gets under way quickly.

Most of the delegates share Washington’s observation that the Articles of Confederation need to be re-worked, given the hard lessons learned from conducting the war and the financial and economic crises that follow.

But having a shared problem is not the same as arriving at a shared solution.

This will prove especially true for the Anti-Federalists who are present. Patrick Henry, who declares “I smell a rat” upon learning of the secrecy pledge. His fear, and that of his faction, is that a re-write of the Articles will result in a victory for those who favor an all-powerful centralized government that behaves like the British monarchy – distant from the people, dictatorial in power, taxing and spending at will, totally eroding the sovereign prerogatives of the individual states.

These concerns, voiced most shrilly by the Anti-Federalists, will set the stage for the vigorous debates that occur over the next four months. A host of diverse and important issues will take center stage at various times:

- How will authority for governing be split between the Federal vs. State levels?

- Does the Federal Government need more than just a Legislative branch?

- How will representation within the Legislature be apportioned across the states?

- How will the interests of small states vs. larger states be protected in Legislative voting?

- How will the interests of states with large vs. small slave populations be balanced?

- How will the rights of any minority groups be protected against the will of the majority?

- What range of powers will be granted to the Legislative Branch?

- How will the government be sufficiently funded?

- Can an Executive Branch be created with enough, but not too much, power?

- How should the Executive be chosen and for how long a term?

- What should the Executive’s role be in relation to the military?

- What checks and balances will exist between the Executive and the Legislature?

- How will state compliance with federal laws be monitored and assured?

- Should there be a Judicial Branch created to oversee the legal system?

- How might such a Judiciary be structured and what powers would it have?

Sidebar: A Short Profile Of Several Less Famous Founding Fathers At Philadelphia

| Name and Age | State | Impact |

| John Dickinson, 54 | Delaware | His “two solar systems” speech clarifies roles of the national government vis a vis the states |

| Oliver Ellsworth, 42 | Connecticut | Gave input on the Connecticut Plan, member of Committee on Detail |

| Elbridge Gerry, 43 | Massachusetts | Challenges South on “counting slaves,” leads Anti-Federalist drive for state legislatures to ratify, refuses to sign the Constitution |

| William Johnson, 59 | Connecticut | Chair of the Committee of Style & Arrangement gave input on the Connecticut Plan, calming influence start to finish |

| Rufus King, 32 | Massachusetts | Serves on Committee of Style & Arrangement |

| Luther Martin, 39 | Maryland | Opposes slave trade, voice for Anti-Federalist faction |

| George Mason, 62 | Virginia | Anti-Federalist who still pushes for supremacy of the people, demands Bill of Rights and second convention, refuses to sign |

| Gouvernor Morris, 35 | Pennsylvania | Aristocratic by birth, a witty debater, makes most motions at convention. Lead author of final Constitution, proposes a strong singular president, openly attacks slavery |

| William Patterson, 41 | New Jersey | Authors New Jersey Plan opens several key issues |

| Charles Pinckney, 29 | South Carolina | Only delegate to openly defend the practice of slavery |

| Charles C. Pinckney, 41 | South Carolina | A lead spokesman for the Southern states, later runs for President as a Federalist. |

| Edmund Randolph, 34 | Virginia | Authors key te pivotal Virginia Plan and Committee on Detail report, calls for a flexible Constitution changing with the times, also amendments, critical role throughout, refuses to sign |

| John Rutledge, 48 | South Carolina | The “Dictator,” a famed General during the war and a planter. Another key spokesperson for South, Chairman of the Committee on Detail, defends need for slavery, supports strong Executive |

| Roger Sherman, 66 | Connecticut | Once a shoemaker, he authors the Enumeration Clause (3/5th slave count) in support of the Great Compromise, input to Connecticut Plan, strong role in the ratification |

| James Wilson, 45 | Pennsylvania | Leads Connecticut Plan with two senators per state enabling the Great Compromise, member of the Committee on Detail, a voice for closure, supports equality of new western states |

Note: Hamilton is 30, Madison 36, Washington 55, Franklin 81. Average life expectancy for white males is 38.in 1787.

May 30, 1787

Governor Edmund Randolph Offers The “Virginia Plan”

On May 30, Governor Edmund Randolph of Virginia gets things under way by proposing a series of nineteen “Resolves” to create a new central government, fundamentally different in scope and procedures from the Thirteen Articles of Confederation.

The primary author of the plan is James Madison.

The First Resolve argues that:

- A national government ought to be established consisting of a supreme legislative, executive and judiciary.

This sentence alone strikes the Anti-Federalists in the hall like a thunderbolt, turning their most fundamental beliefs upside down. The Thirteen Articles guaranteed the “sovereignty” of the States, and now the national government claims the supremacy of its laws over individual state laws.

Later comes another blow to “state sovereignty” in the Seventh Resolve. Under the Thirteen Articles, each State enjoys equal power — “one vote” apiece — in deciding on new legislation. The tiniest state of Delaware has as much say in the outcomes as the largest state, Virginia. But under Randolph’s proposal, the number of votes would vary according to the size of its population. Virginia might now have 13 votes against 1 for Delaware.

- The national legislature ought to accord to some equitable ratio of representation – namely in proportion to the whole number of white and other free citizens…and 3/5ths of all other persons, except Indians…

The Second Resolve divides the national legislature into two chambers, a clever move that will eventually result in a House of Representatives and a Senate, yielding crucial compromises with the Anti-Federalist and small state factions.

- That the national legislature ought to consist of two branches.

The Third Resolve ensures that legislators in the first chamber be chosen directly by the people – rather than being “named” by those already serving in the state’s legislature.

- That the members of the first branch of the national Legislature ought to be elected by the People of the several States for the term of three years.

A Fourth defines the second legislative chamber, with presumably more senior figures serving seven-year terms, chosen by state officials.

- That the members of the second Branch of the national Legislature ought to be chosen by the individual Legislatures. to be of the age of thirty years at least. To hold their offices for a term sufficient to ensure their independency, namely seven years.

The Sixth Resolve lays out a broad scope for the new national legislature, covering issues “beyond the competence” of the individual states or where the “harmony” across all states is in play. It also grants the national body power to “negative” (i.e. overrule) state laws which violate the common interests of the nation.

- To legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent: or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation. To negative all laws passed by the several States contravening, in the opinion of the national Legislature

The Executive Branch of the new government is profiled in the Ninth Resolve. Randolph calls one person to be chosen by the national Legislature. They will serve seven years, charged with seeing that the laws are carried out, and at risk of being impeached for violations.

- That a national Executive be instituted to consist of a single person. To be chosen by the National Legislature for the term of seven years with power to carry into execution the national Laws…and to be removable on impeachment and conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty.

The Tenth Resolve gives the Executive power to veto any legislative act, unless overturned by a 2/3rds vote.

- That the national executive shall have a right to negative any legislative act: which shall not be afterwards passed unless by two third parts of each branch of the national Legislature

Resolves Eleven to Thirteen establish the Judicial Branch of government, along with various operating rules.

- That a national Judiciary be established to consist of One Supreme Tribunal. The Judges of which to be appointed by the second Branch of the National Legislature to hold their offices during good behavior

The remaining eight Resolves fill in other considerations for the new government, among them are the admission of new states to the union and future passage of amendments to the Constitution.

The “Virginia Plan” offered by Randolph on May 30 proves critical to the life of the Convention.

It serves as the starting point for the debates that follow. Despite the appearance of other Plans, delegates always cycle back to the Virginia Plan’s basic frameworks when decisions are required. Ironically the man who proposes the plan, Randolph, will be one of only three men who refuse to sign the final document he has done so much to advance.

June 15, 1787

New Jersey Proposes A “Small State” Alternative

Once the Virginia Plan is on the table, two things become immediately clear: a House of Representatives dealing with the nation’s important issues enjoys overwhelming support — while the proposed composition of this House is intensely divisive.

The sticking point lies with the smaller states, who have no intention of surrendering their power in the new legislature to the larger states. If Virginia is to end up with thirteen votes and Delaware with just one, then Delaware will never support the new Constitution.

After fifteen days of paralysis over this “apportionment” barrier, the Attorney General of New Jersey, William Patterson, offers the Convention his “small state alternative.”

What Patterson proposes on the Legislative Branch is that the unicameral approach existing under the Thirteen Articles be kept in place, with each State retaining its equal voting power.

Proposed Plans For The New Legislature

| Virginia Plan | New Jersey Plan | |

| # of Chambers | 2 – bicameral | 1 – unicameral |

| Apportionment | Based on state population | Every state has 1 vote |

| Power Derived From | Popular voting in House | States Legislators |

When this is put to a vote, the New Jersey alternative goes down, with only three states favoring it against seven for the Virginia Plan and two states divided.

While this loss is decisive, it fails to resolve the matter – with several small states threatening to go home rather than surrender their “sovereignty.”

Despite this fundamental failure, the New Jersey Plan announces several other ideas that will become relevant as the sessions continue.

- Congress can raise funds by tariffs and taxes collected from the states.

- A federal Treasury will be set up to handle revenue and expenses and quality assure the money supply.

- Congress will regulate interstate and foreign commerce.

- The Executive branch will include several people, elected by Congress, for one term only.

- A Supreme Tribunal appointed by the Executive will resolve legal disputes (borders, treaties, impeachment).

- A standing army will be created, with States contributing troops in proportion to their population size.

- Military officers will be approved jointly by States and Congress.

June 18, 1787

Hamilton Announces His Revolutionary Option

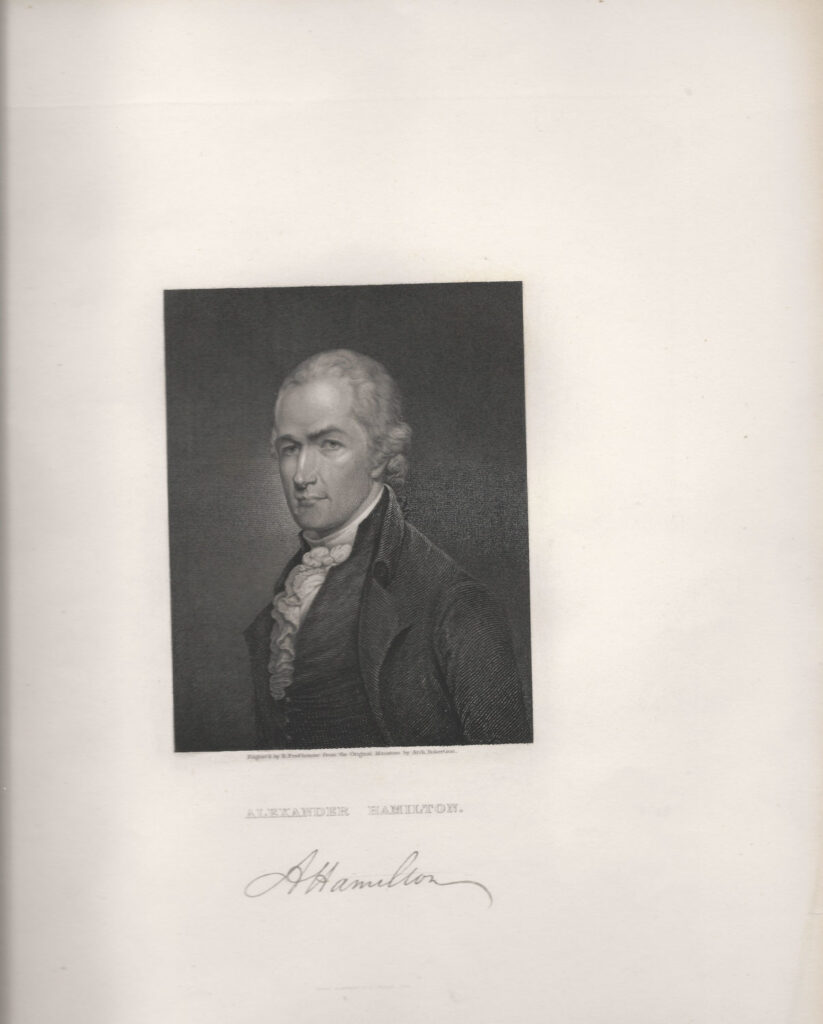

The next move belongs to Alexander Hamilton of New York, who has lobbied to hold this Convention over seven long years. On June 18 he addresses it in an impassioned six hour speech.

The 32 year old Hamilton is already a renowned Federalist, whose standing traces to his father-in-law, Major General Philip Schuyler of Revolutionary War fame, and to none other than George Washington, whom he has served as Chief of Staff during four years on the battlefield.

Despite these credentials, many view the British West Indies born Hamilton as a “foreigner” who, as Jefferson later writes, has been “bewitched and perverted by the British example.”

Indeed Hamilton’s speech is a paean to the British government, which he calls “the best in the world.”

He advises the Convention to adopt the core British principles, especially that of an all-powerful Executive. He proposes that this be a single person, titled “Governor,” with power comparable to a monarch, and holding office for life.

He ought to be hereditary, and to have so much power, that it will not be in his interest to risk much to acquire more. The advantage of a monarch is this – he is above corruption – he must always intend, in respect to foreign nations, the true interest and glory of the people.

Like many others, Hamilton is very suspicious of a “pure democracy,” fearing its tendency toward momentary passions and mob-like swings in governance.

The voice of the people has been said to be the voice of God…but it is not true in fact.

Neither does he trust the States, who “will prefer their particular concerns to the general welfare.”

Now is the time, Hamilton argues, for the United States to act as one nation, unified and powerful, capable of taking its place alongside Britain, France and Spain on the world stage. This will be possible only if power is placed in the hands of responsible statesmen who will devote their lives to advancing the welfare of the nation.

Hamilton’s views are those of the Federalist faction writ large.

They are immediately rejected by his two fellow delegates from New York, Robert Yates and John Lansing, both pledged to the virulently Anti-Federalist Governor, George Clinton, now serving his fourth term in office.

Others in the room signal their displeasure toward Hamilton’s Plan in their silence. Two days later, disheartened, Hamilton heads home for a two month hiatus from the Convention.

His fierce commitment to a powerful Union is appreciated by all, but his vision for an Executive is far too reminiscent of King George III for his audience.

July 5, 1787

Roger Sherman Shares The “Connecticut Plan” In Committee

Another two weeks pass with progress stalled over the apportionment of seats in the new Legislature.

A committee is set up to deal with the matter, chaired by Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts and including Roger Sherman of Connecticut — “a man who never said a foolish thing” according to Jefferson.

On July 5 Sherman presents a compromise to Gerry’s Committee, intended to break the logjam.

- The Legislative branch will have two chambers (House and Senate), according to the Virginia plan.

- The number of House seats a state enjoys will be based on its population count in a Census.

- The number of Senate seats for each state will be set equally, at two.

- State legislatures will elect its two senators.

- To “pass” Congress, all bills must gain majorities in both chambers.

Proposed Plans For The New Legislature

| Virginia Plan | New Jersey Plan | Connecticut Plan | |

| # of Chambers | 2 – bicameral | 1 – unicameral | 2 – bicameral |

| # seats in House | Based on state population | Every state has 1 | Based on state population |

| # seats in Senate | Based on state population | — | Every state has 2 |

Sherman’s proposal leaves the Virginia Plan untouched when it comes to having two chambers in the Legislature, and having apportionment in the House based on each state’s population count.

But in the Senate he restores the equality of the Thirteen Articles by allocating two seats to each state, regardless of their size.

This proposal becomes known as the “Connecticut Plan,” in honor of the three state delegates who have crafted it – Sherman, Dr. William Johnson, and Oliver Ellsworth.

Gerry supports the plan and promises to take it to the full assembly.

As the Connecticut Plan is taking shape in committee, the atmosphere in the hall is rapidly deteriorating.

It reaches a low point on July 10 when the two remaining New York delegates, Lansing and Yates, announce they are giving up and going home, the first open defections so far. As he leaves, Lansing offers his summary of the various plans:

Utterly unattainable, too novel and complex.

Hearing of these departures, Washington writes that same day:

I almost despair of seeing a favorable issue to the proceedings of the Convention.

Everywhere he looks, Washington sees the “monster of state sovereignty” blocking the path to progress.

On one hand, the smaller states balk at a possible loss of power to the larger states; on the other, the larger states feel like they are forfeiting their authority to a new “national” power. As James Wilson of Pennsylvania puts it…

If no state will part with any of its sovereignty, it is in vain to talk of a national government.

July 9-13, 1787

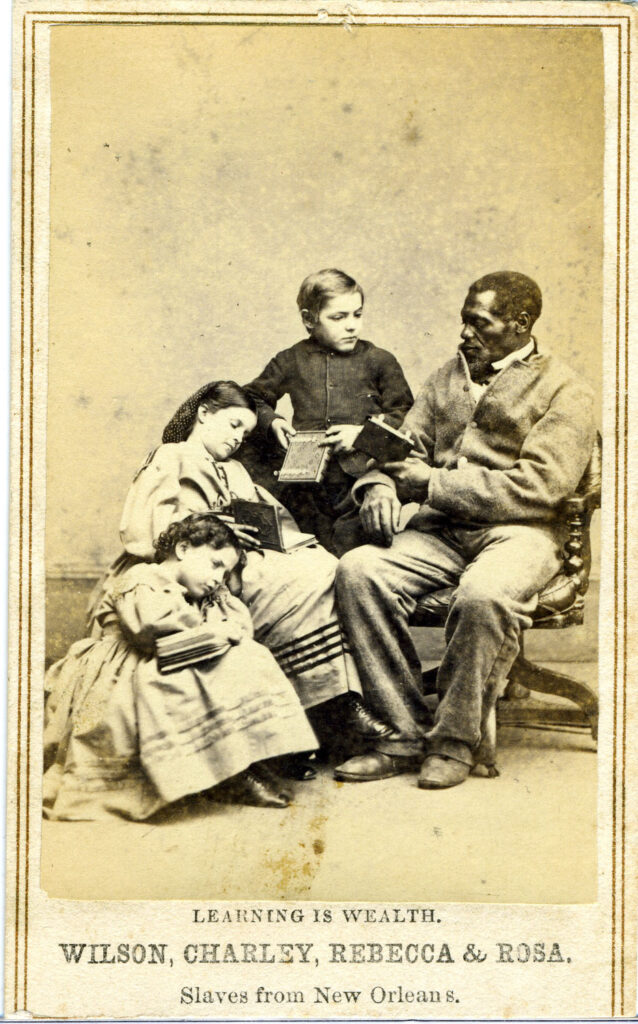

Sharp Conflicts Over Slavery Almost Derail The Convention

And now another issue emerges – one that is capable of blowing up the entire Convention.

That issue is slavery.

Its presence has been reptilian all along, and now it strikes over “apportionment” – the process by which states will be allocated seats in the House.

The question becomes: will the Northern states allow the South to include its slaves in their population counts – or not?

In his “records,” James Madison picks up on the crucial nature of this issue.

The most important question regarding the make-up of the legislature was whether or not to count slaves.

The mathematics associated with “if and how” the slaves are counted register immediately with the politically savvy men present, both South and North.

A 1775 estimate says that some 450,000 slaves live in the South, roughly 40% of its entire population — while in the North, Black people number around 50,000 or 5% of the total.

The Importance Of Slaves To Various States Population Counts In 1775

| Section | States | Whites | Slaves | Total | % Black |

| Lower South | Ga, NC, SC | 247,000 | 171,000 | 418,000 | 41% |

| Upper South | Va,Md,Del | 481,000 | 282,000 | 763,000 | 37 |

| Mid-Atlantic | Pa,NY,NJ | 462,000 | 30,000 | 492,000 | 6 |

| New England | Con,RI, NH, Ma | 621,000 | 19,000 | 640,000 | 3 |

| 1,811,000 | 502,000 | 2,313,000 | 22% |

Nothing short of “regional power” in the Legislature therefore rests on the “counting” outcome.

Assuming that slaves are counted fully in each State’s official population, and one seat is allocated for every 40,000 residents, the Legislature would be divided 30-28 in favor of the South.

On the other hand, if the slaves do not count at all, the North ends up with a commanding 27-18 majority.

Number Of Votes In House Depending On How Slaves Are Counted

| Section | States | Slaves = 1 | Slaves = 0 | Difference |

| Lower South | Ga, NC, SC | 11 | 6 | +5 |

| Upper South | Va,Md,Del | 19 | 12 | +7 |

| All South | 30 | 18 | +12 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | Pa,NY,NJ | 12 | 12 | — |

| New England | Con,RI, NH, Ma | 16 | 15 | +1 |

| All North | 28 | 27 | +1 | |

| Grand Total | 58 | 45 | +13 |

As the debate here unfolds, the depth of the dilemma facing the new nation around slavery becomes apparent.

What began as an economic initiative benefitting both the South and the North is now the source of deep division between the two regions.

The North wishes to rid itself of the entire “African problem.” Meanwhile, the South is dependent on slavery to prosper.

Jefferson’s words capture the dilemma best.

Slavery is like holding a wolf by the ears – one can neither safely hold him, nor safely let him go.

Conflicting motives spill over into personal distrust.

If the North gains dominance in the new “national” Legislature, will it try to force the South to follow its lead and “let go” of slavery?

This is what’s on the minds of the Southern delegates as the “slave counting” debate opens up.

Southerners quickly begin to make their case. The Anti-Federalist Virginian, George Mason, first claims personal disdain for slavery, then blames the British for forcing it upon his region. Given this historical context, Mason argues that the Africans should be viewed as a “national burden,” shared equally by the South and North.

This infernal traffic originated in the avarice of British merchants, and they checked the attempts of Virginia to put a stop to it.

Slavery discourages arts and manufactures. The poor despise labor when performed by slaves. They prevent the immigration of whites, who enrich and strengthen a country. They produce the most pernicious effect on manners.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of Charleston is next to weigh in, admitting openly that after slavery took hold in the South, several states, including his own, have become economically dependent on it.

South Carolina and Georgia cannot do without slaves.

His fellow South Carolina delegate, Rawlins Lowndes, reinforces this theme — then openly lashes out against the North, accusing them of trying to rob his region of its wealth.

Without negroes, this state is one of the most contemptible in the Union. Negroes are our wealth, our only natural resource.

Yet behold how our kind friends in the North are determined soon to tie up our hands, and drain us of what we have.

Pinckney’s cousin, also named Charles, becomes the only member arguing not only that slaves are good for the South, but that the institution lifts the slaves from savagery to civilization.

To drive these views home, both the South Carolina and Georgia delegations threaten to leave Philadelphia unless the slaves are included in their population counts.

Two Northerners will have none of this, and stand nose to nose against their Southern counterparts.

The first is the merchant, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, who asks how the South can assert that slaves are “property” – the moral equivalent of cattle – and simultaneously argue they are “persons,” the same as white men, when it comes to the population count?

Blacks are property and are used by the south as horses and cattle in the north, so why should their representation be increased on account of the number of slaves?

Gerry’s views are seconded by the pugnacious peg-legged Federalist from New York, Gouvernor Morris, who leads all of his colleagues in speaking time and motions offered over the entire convention.

Morris is one of the few delegates unrestrained in his opposition to slavery, and his wish to have it end.

His attack on the Southern position is devastating, and will ring down the decades to come.

Like Gerry, he asks whether the slaves are property or persons? Surely the South cannot have it both ways.

On what principle shall slaves be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them Citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included (in calculating votes)?

The inhabitant of Georgia and SC who goes to the coast of Africa and in defiance of the most sacred laws of Humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections and damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a Government instituted to protect the rights of mankind than the citizen of Pennsylvania or New Jersey who views this practice with laudable horror.

At this point the debate has become personal, and threatens to turn into a runaway firestorm. To save the day, a delegate from Pennsylvania, James Wilson, offers up a possible compromise.

July 13, 1787

The “Enumeration Clause” Counts Slaves As 3/5th Of A Person

Wilson is born in Scotland, mingles with leading Enlightenment thinkers such as David Hume and Adam Smith, emigrates to America in 1776, and becomes a successful lawyer in Philadelphia. As a pamphleteer, he argues that Britain has no right to raise taxes on the colonies because they have no representation in Parliament. When the war breaks out, he serves as a Brigadier General in the Pennsylvania militia. He plays a large role in shaping the Connecticut Plan, and is considered by many to be the most learned man at the 1787 convention

When confronted with the dispute over whether or not to include Black people in a state’s population count, his solution is positively Solomon-like in nature. He proposes to split the difference between the two sides.

Again relying on simple math, he calls for weighting slaves as 3/5th of a person for the sake of determining each states official population count. When applied to estimated head counts from 1775, the result projects to 28 seats in the House for the North and 25 for the South.

Compromise Under 3/5th Enumeration Clause

| Section | States | Slaves = 3/5th |

| Lower South | Ga, NC, SC | 9 |

| Upper South | Va,Md,Del | 16 |

| All South | 25 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | Pa,NY,NJ | 12 |

| New England | Con,RI, NH, Ma | 16 |

| All North | 28 | |

| Grand Total | 53 |

This gives the North prospects for a slight majority, albeit not the commanding lead if slaves were excluded entirely from the calculations.

On the other hand, the South get partial credit for their slaves without needing to accede to the notion that they are “full persons” rather than “property.” Besides which, Southerners firmly believe that future census figures will show much greater population growth in their region given its favorable climate – an outcome that fails to materialize in the long run.

Wilson’s “solution” will eventually be captured in the infamous “Enumeration Clause” of the Constitution, favoring whites over both Black and Native people.

Article I, Section 2. Representation and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, and three fifths of all other Persons.

“All other Persons” is the euphemism chosen to avoid the indelicate word “slaves.”

To allow the convention to move forward, they are to “count” as 3/5ths of a white man — somewhere between cattle and human beings.

The importance of Wilson’s compromise cannot be overstated, and in later years many will regard him as the “unsung hero of the Convention.”

Madison’s “convention notes,” withheld until 1840, state flat out that the North-South divide over slavery was the biggest threat to finalizing a new government.

I was always convinced that the difference of interest in the US lay not between the large and small but the northern and southern states…and it was pretty well understood that the institution of slavery and its consequences formed the line of discrimination.

With the Enumeration Clause in place, the Connecticut Plan is almost ready to move from the Gerry Committee to the full floor.

July 16, 1787

The Northwest Ordinance Provides A Firm Truce On Slavery In The New Territory

On July 16, another piece in the new government puzzle falls into place. It is called the Northwest Ordinance, often regarded as the third most important document (behind the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution itself) in the formation of the United States.

It deals with a topic on the mind of all delegates from the first day of the Convention – what to do with the new territories west of the Appalachians, won from Britain, and then ceded to the Federal Government in The Land Act of 1785. Surveys are already under way to divide this land into plots, but many questions remain. How will it be settled and governed? Will it involve the creation of new States and, if so, how will they be tied into the union?

Finally, will slavery be allowed in this new land – or not?

As a practical matter, some 100,000 settlers have already put down stakes in “the west” by 1787. They have also christened their “territories” with a host of new names – some lasting (Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee) and some that will fade away (Transylvania, Westsylvania, Franklin).

The Northwest Ordinance agreed to on July 16 says that the land will be divided into 3-5 new Territories, with exact borders to be laid out when the time comes to do so. Once the population in a new Territory reaches a threshold of 5,000 settlers, the Federal Congress will appoint a Governor, a Secretary and three Judges to provide administrative oversight. The Territory may also elect a representative to attend the House of Representatives as a non-voting member.

When a Territory achieves a threshold population of 60,000, it can then write and pass a local constitution, identify its boundaries, and apply for formal admittance to the Union as a new State.

These same “governance principles” are to apply across the South, as soon as documents are signed to cede certain lands still in dispute. When this is completed, in 1789, a Southwest Ordinance is signed into law.

A vigorous debate follows on whether new States will enjoy “equal treatment” vis a vis the original thirteen. The answer is eventually “yes” by a 5-4 floor vote, despite a lasting eastern delegate bias against sharing power with “backwards westerners sporting coonskin caps and twangy dialects.”

What tips the scales here is genuine fear that the Appalachian Mountains, and the westward flowing rivers it feeds, will forever tie the new states to Spanish settlements along the Mississippi River, rather than to the new American union. This is an outcome that few are willing to risk.

All told then, the Northwest Ordinance provides for orderly movement of settlers into the new territory in a way that also binds them to the union – albeit ignoring the rights of the Native peoples already present.

Remarkably the Ordinance also defuses the rising tensions over slavery!

It does this through a last second article added by Nathan Dane of Massachusetts, later referred to as the “father of American jurisprudence.” Dane is not a delegate to the Convention, but is a renowned legal scholar called upon to draft the Ordinance. The article he includes is simple but profound, and, to Dane’s surprise, readily approved by the body.

Art. 6. There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted: Provided, always, That any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service as aforesaid.

Article 6 lays out a geographical line certain – in this case the course of the Ohio River – and openly declares that the institution of slavery will be prohibited to its north and permitted to its south.

In agreeing to this line of demarcation, the South acknowledges that the North wishes to ban the spread of slavery in “its region” of the country.

The North, meanwhile, agrees to respect continuation of slavery in the South, and to facilitate it by supporting the return of any run-away slaves who cross the Ohio River.

This definitive Ohio River line will quell some of the acrimony left over the subject of slavery, both in the hall and over the next three decades.

It also opens the door for a deal on “slave trading,” agreed to a month later, on September 6. The practice will be allowed to continue for twenty more years, but then cease in 1808. During that period the Congress will collect a tax of $10 on every imported slave.

While at first glance, this 1808 ban on importing more slaves may appear detrimental to the South; that is not the case at all. The reason being that, in twenty years, domestic owners expect to “breed” a sufficient inventory of “excess slaves” for sale, thus keeping the profits for themselves rather than handing them over to the importers. This “breeding scheme” is particularly important to the state of Virginia, which is already seeing that selling slaves can be more lucrative than selling tobacco.

July 16, 1787

A “Great Compromise” Defines The Legislative Branch Structure

One final roadblock needs resolution before the Legislative branch plan is finalized. It involves fear among the larger states that “money bills” (taxing and spending) coming out of the “equalized Senate” might be tilted unfairly against them by the smaller states.

Ben Franklin steps forward with a solution that becomes known as the “Origination Clause” – stating that all money bills are to originate in the House and cannot be unilaterally changed by the Senate. In exchange for losing some financial powers, the Senate will be given several important “advise and consent” assignments – approving certain judges and ambassadors, ratifying treaties, trying impeachment cases.

The Convention is well in need of good news, and on July 16 it arrives, in the form of “The Great Compromise,” Mr. Sherman’s plan to structure the nation’s new bicameral Congress, aided by the Northwest Ordinance.

Henceforth the “will of the American people” is to be expressed through a House of Representatives, with members chosen state by state in direct elections and apportioned according to a population count which factors in slaves.

A second body, the Senate, will also weigh in, with large and small states each having two members, to be elected by local legislatures.

All new laws must pass in both chambers for approval.

Members in the House will be elected by the people to two year terms of office. To qualify they must be citizens for a minimum of seven years, and residents of the state, and be at least 25 years old.

Senators will be named by state legislatures for six-year terms. To qualify they must be citizens for a minimum of nine years, a state resident, and at least 30 years old.

The Legislature must meet at least once a year, for sure on the first Monday in December. All members who participate will be paid out of the National Treasury with amounts ascertained by law.

Final Plan For The New Legislature

| # of Chambers | 2 – bicameral |

| # seats in House | Based on state population |

| # seats in Senate | Every state has 2 |

On July 16 then, the logjam is broken – and an agreement is reached on the structure of the Legislative Branch.

July 16, 1787

America Will Be A Republic, Not A Pure Democracy

The “Great Compromise” reflects the tensions felt by many delegates around “how far to trust” the will of the masses, and of the majority.

Clearly the new government intends to respond to the people’s will. Both James Madison and George Mason are crystal clear about this.

The people are the fountain of all power… We must resort to the people…so this doctrine with supreme authority over the government. Be cherished as the basis of free government.

“Majority rules” will also be the norm, as Alexander Hamilton points out.

The fundamental maxim of government…requires the sense that the majority should prevail.

From these observations one might expect the Convention to have arrived at a “pure democracy” – with every future decision resolved through a direct poll of the people, on a winner-take-all basis.

But this is not what the delegates decide. Instead of a pure Democracy, their solution is to create a Republic.

I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands.

Between the people and the law stand “representatives,” charged with adding their own wisdom and experience to the mix.

The explanation for this goes beyond the geographical impracticality of direct polling, to underlying suspicions that “the people” can easily transform into a mob, inflamed by short-term passions, liable to act out of rashness rather than reason.

There is also fear that, left to their own devices, “the people” may be inclined to trample on the rights of various minorities within the population – for example, the landed gentry, as none other than Madison points out.

In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of landed proprietors would be insecure… Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests, and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority. The Senate, therefore, ought to be this body; and to answer these purposes, they ought to have permanency and stability.

For every Ben Franklin or George Mason in the hall expressing unequivocal faith in the intrinsic wisdom of the masses, there are others, like Alexander Hamilton and John Sherman, who are much less confident.

That committed democrat, Thomas Jefferson, is another. As he writes, the odds of “mischief” are high whenever men and motives are joined.

In questions of power then, let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the constitution.

John Adams, so simultaneously unlike and like Jefferson, sees it the same way — any group of men given too much power will become “ravenous beasts of prey.”

The message then from the worldly founders in Philadelphia is that governments are delicate in nature and prone to going off course, either through the masses as mobs, or individual men as dictators.

In turn, the path to preserving the values of self-government lies in a series of “checks and balances,” Jefferson’s “binding chains of the constitution.”

Representatives in the House will “check” the masses; the Senate will “check” the House. Together they will “balance” the wishes of the majority against the proper concerns of the minority.

With that much settled, the delegates turn their attention to the Executive Branch.

Late July 1787

A President Of The United States Will Head The Executive Branch

Once again the “Virginia Plan” of May 30 becomes the starting place for discussions, this time on structuring the Executive Branch. It calls for a Council of several men selected by Congress, charged simply with insuring that the laws of the land are being properly carried out.

Then comes Hamilton on June 18 with his radically different approach – insisting that the Executive be one man, titled Governor, serving for life, with powers approaching those of a monarch.

Neither plan feels right to the full body. Somewhere there must be a middle ground between the Executive as fairly minor pawn or mighty king.

A month passes before the ubiquitous Gouvernor Morris of Pennsylvania rises with an alternative on July 19.

Morris argues that a strong Executive, one man for sure, is needed as a “check” on the Legislative Branch, a final “guardian of the people.”

- The Executive will be titled the President of the United States, and called “His Excellency.”

- His term will be four years, but he is allowed to continue in office for as long as he is re-elected.

This approach sits well with the majority, although several concerns are voiced.

The Anti-Federalist warns that it will become the “fetus of monarchy.”

James Wilson and James Madison worry that a President “directly elected by the people,” might be too prone to short-sighted populist urgings rather than what is best for the long term.

On top of this, a direct election raises the same questions about state sovereignty that arose with the Legislature. Wouldn’t the states with larger populations and therefore more votes dominate the will of their smaller neighbors?

What falls out here is the creation of an “Electoral College” charged with actually choosing the President.

- He will be chosen by “electors” from each State, who will be “named” by the State’s legislature.

- Each State will have a number of electors that match their total seats in Congress.

- Each “elector” will nominate two men for the position, including one not from their home state.

- The man with the most votes will become President; second most will be Vice-President.

- In case of a tie, House members will be called upon to break it.

This approach again involves a balancing act.

The bigger states do end up with more voting power – but this seems less threatening in the Executive Branch than in the Legislature, where new laws are originating.

The will of the masses is to be harnessed by “electors,” chosen by state officials, exhibiting statesmanship and wisdom in casting their two ballots.

Over 60 separate votes are taken at the Convention before the process for electing a President is resolved.

The outcome also leads to the office of the Vice-President – to be filled by the runner-up in the Electoral College voting. The exact duties of the Vice-President are vague all along. Most feel he would act as a “stand-in” in case the President died, until the Electoral College had time to gather and pick a true replacement. Other than that, he is given the mostly ceremonial job of ex-officio President of the Senate, with the power to break tie votes.

It is abundantly clear that the new president is to be more than a figurehead and less than a monarch. So what exactly are his powers?

July 26, 1787

Presidential Powers are Defined

Resolving the Executive’s role requires another wrestling match between Federalists and Anti Federalists.

In the end, the Convention retains the two powers identified in the “Virginia Plan” – to “take care that the laws are faithfully executed” and to make a host of “appointments,” such as ambassadors and federal judges, with the Senate’s consent.

Layered on top of these are a broad range of add-ons. Some are very specific: vetoing bills, writing government checks, granting pardons, making treaties, receiving foreign dignitaries, and commissioning officers.

One other power is also on thedelegates’ minds, the role of the President in any future warfare, especially involving a sudden invasion. At the time, this prospect is by no means far-fetched, with the British in Canada and Spain still controlling Florida and all land west of the Mississippi River.

The Revolutionary War has proven the futility of hoping for Congressmen from thirteen states to agree on military strategy in timely fashion. Organizing a standing army to speed up action is suggested, but rejected by some who are committed to State militias and fear a military coup. As Madison writes:

Oppressors can tyrannize only when they achieve a standing army, an enslaved press, and a disarmed populace.

Of course, the “solution” to these concerns is before their very eyes, sitting at the front of the hall, in the person of George Washington – one man with mastery over both military and political affairs. Some, like his aide Hamilton, might wish to make him king; others simply wish that his persona can be cloned over time in future Presidents. But for now it’s clear the delegates intend to look to the Executive to oversee military affairs, if and when war arises.

The President shall be Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States and of the Militia of the several States when called into the actual service of the United States.

A final addition to Presidential powers is remarkably open-ended – to do whatever is required “to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution.” They expect a wise statesman-like President who nudges Congress toward actions in the national interest and vetoes harmful legislation when he senses it.

In the long arc of history to follow, America will occasionally swear in a President who lives up to these wishes.

The Enumerated Powers Of The President Circa 1787

| Article I | Power To |

| Section 7, clauses 2-3 | Approve or veto Bills and Resolutions passed by Congress |

| Section 9, Article II | Write checks (via Treasury) pursuant to Appropriations made by Congress |

| Section 1, last clause | Preserve, protect and defend the Constitution |

| Section 2, clause 2 | Serve as Commander-in-Chief when Congress calls the army to service Require Executive department officers to write up their assigned Duties Grant Reprieves and Pardons for offenses against the United States |

| Section 2, clause 3 | Advise the Congress periodically on the State of the Union |

| Section 3 | Recommend to Congress such measures as he deems wise Convene one or both chambers of Congress on extraordinary occasions Receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers Take care that the Laws are faithfully executed Commission all the Officers of the United States |

August 6, 1787

An Enumerated List Of Powers Is Approved For The Congress

By the end of July, the delegates begin to sense that what they set out to do back in May might actually be within their reach. A whole new government, respectful of each state’s sovereignty, but bound together by a central authority dedicated to the common good for all.

The time has come for the many lawyers in the room to worry about the fine print – especially codifying the exact powers of the new Congress they intend to create. The “Virginia Plan” simply assigns it “any tasks the States are incompetent to do.”

This “left-overs” definition is far too vague for the delegates, and on July 26 they create a “Committee of Detail” to enumerate the powers one by one.

This very powerful group is chaired by John Rutledge of South Carolina, known to colleagues as “the Dictator” for his dual role during the war as Governor of his state and Commander-in-Chief of its military forces. He is joined by Edmund Randolph of Virginia, Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, James Wilson of Pennsylvania and Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts.

After a two week adjournment, the committee reports out on August 6, including a list of about thirty specific recommendations. Edmund Randolph, who authored the “Virginia Plan,” also crafts this document. In a Preamble, he expresses his hope that each power is clear as written and yet flexible enough to accommodate external change. Thus his stated goals:

- To insert essential principles only; lest the operations of government should be clogged by rendering those provisions permanent and unalterable, which ought to be accommodated to times and events: and

- To use simple and precise language, and general propositions, according to the example of the constitutions of the several states.

At the top of the list is assigning the “power of the purse” bestowed to the new Congress. Instead of the futile reliance on “voluntary State donations” under the Thirteen Articles, the House is authorized:

To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the U.S.

Delegates, however, remain very aware of America’s visceral opposition to burdensome taxes, tracing from the Boston Tea Party to Shay’s rebellion.

Thus “direct” taxes on a given person’s income or wealth are ruled out in favor of “indirect” taxes — “Duties or Imposts” (later called “Tariffs”) on imported or exported goods, and “Excises” aimed mainly at taxing the manufacture, sale or consumption of certain goods (e.g. spirits).

Another important financial change gives Congress the power:

To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.

This takes control of the money supply out of the hands of State banks (with their often grossly inflated “bills of credit” printed locally) and places it at the Federal level.

A third proposal relates to war powers:

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

The enumeration goes on, granting Congress the authority to: raise armies, call forth the militia, build a navy, suppress insurrections, negotiate and enforce treaties, regulate commerce, establish post offices and postal routes, promote science and the arts, issue patents, set up appeals courts, punish counterfeiters and high seas pirates, oversee the naturalization process.

Finally the Federalists slip in one last “catch-all” clause, authorizing Congress to:

Make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States.

This “necessary and proper” clause will boomerang after the original Constitution is signed and the Convention adjourns. It will result in a set of ten amendments known as The Bill of Rights, not approved until December 1791, wherein the Anti-Federalists succeed in reining in the scope and power of the Federal Government.

Mid-August 1787

Nagging Divisions Over Slavery Persist

While the 3/5ths Clause has enabled the convention to move forward, issues surrounding slavery continue to touch a raw nerve every time they surface.

Southerners are already becoming wary of Northern intentions, and they press hard for three guarantees in the final Constitution:

- Continuation of the slave trade with Africa until 1808.

- A promise that Northern states will return fugitive slaves to the South.

- Iron clad assurance that slavery shall continue over time in America.

Push back materializes on all counts. Gouvernor Morris assails the entire practice of slavery.

I would never concur in upholding domestic slavery.

Maryland’s Luther Martin resists the further importation of slaves.

It is inconsistent with the principles of the Revolution and dishonorable to the American character to legitimize the importation of slaves in the Constitution.

Even the Virginia plantation owner, James Madison, expresses discomfort over the high moral aims of the new government and the suspect ethics of human bondage.

I think it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.

Given these sentiments, it is not by accident that the final Constitution, largely drafted by Madison himself, never once references the word “slavery” in its text.

But the debates prove that dismissing slavery in writing is far easier than resolving it in practice. Just below the outward mask of diplomacy, the two sides remain far apart on the issue.

- The North wishes it could wash its hands of the “African problem,” especially since their presence is no longer important to economic progress in the region. Perhaps the new nation, in service to white men, would be best served by turning back the clock and shipping the enslaved people off to Africa?

- The South rejects this thinking entirely. For better or for worse, the economic well-being of its entire region now rests on slavery. The North must recognize this fact as well as its original complicity in supporting slave trading in the first place. If true comity is to prevail within the new government, the North needs support the continuation of slavery, not try to erase its presence.

As John Rutledge of South Carolina puts it:

I would never agree to give a power by which the articles relating to slaves might be altered by the States not interested in that property and prejudiced against it.

Recognizing fundamental impasses here, the nearly exhausted delegates simply end with a temporary truce on slavery based on compromises already reached.

Late August 1787

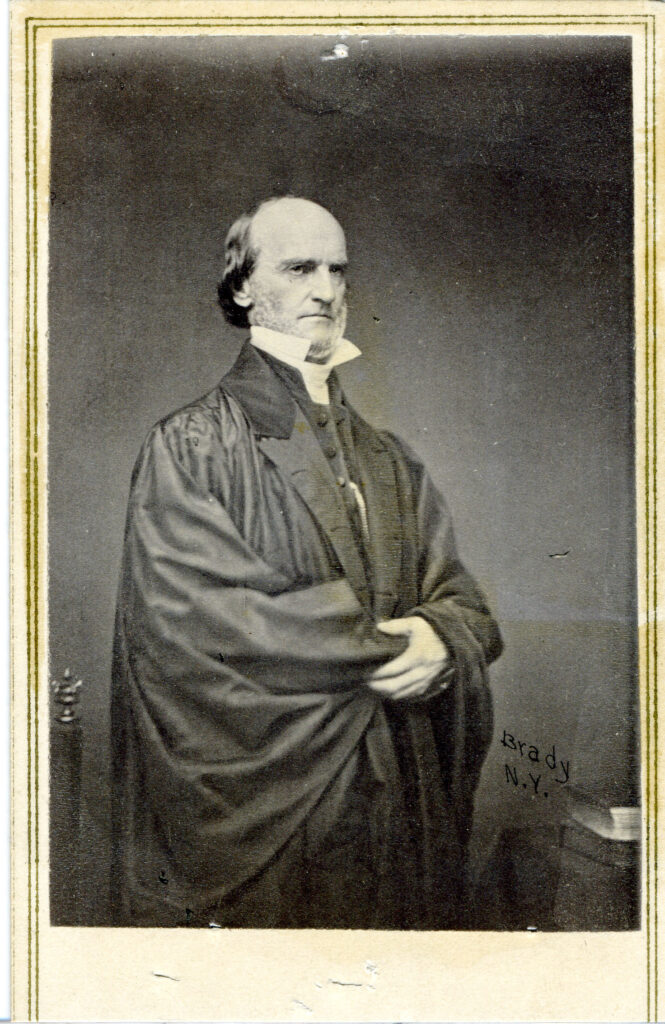

A Vaguely Defined Supreme Court System Is Approved

As time begins to run out on the Convention, delegates return to the third branch of government identified in the “Virginia Plan,” the Eleventh Resolve:

- That a national Judiciary be established to consist of One Supreme Tribunal. The Judges of which to be appointed by the second Branch of the National Legislature, to hold their offices during good behavior.

The idea for a Judicial Branch at the Federal level springs from the conviction that Legislatures – locally or nationally – must be prohibited from passing laws that violate the principles laid out in the Constitution. As Alexander Hamilton says:

No legislative act contrary to the Constitution can be valid…It therefore is the duty of the courts of justice…to declare all acts contrary to the Constitution void.

But who would be responsible for policing the violations?

The “Virginia Plan” posits a “Council of Revision,” composed of the Executive and several members of a National Judiciary, who would review new laws before they are finalized, and then “nullify” any deemed to be contradictory to the “intent” of the Constitution.

Resistance to this “Council” is widespread and varied.

- A review of every new law before it takes effect will paralyze the entire system.

- It would signal distrust and disrespect for the good intentions of the Legislative Branch.

- Power over the law would be transferred to a handful of judges, none of whom are elected by the people.

- Including an Executive who may have no legal training makes little sense.

Eventually a proposal to review laws only after they have taken effect, and only if they are challenged for non-compliance with the Constitution, wins support, as does dropping the Executive from the “Council” in favor of trained lawyers only.

As time runs out on the Convention, the assembly settles for Article III of the Constitution:

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.

The effect of this is to signal the wish for a Supreme Court, with details to be worked out later by the Congress.

Two years will pass before the Judiciary Act of 1789 provides some definition. The Supreme Court will consist of a Chief Justice and five associates who will be nominated by the President and approved by the Senate. Their duties will include “riding the circuit” – traveling twice a year to each of thirteen “judicial districts” across the country to identify laws that may be violating the Constitution. This Act also creates the office of Attorney General, the chief Federal lawyer, whose role is to prosecute all suits that come before the Supreme Court, and to provide general legal advice the President and other government officials.

Over time the Supreme Court will define its own scope and authority, often to the dismay of future Presidents, Legislators and various segments of the public.

Early September 1787

Ratification Procedures Are Debated

The delegates know now that they will soon be asked to sign their names to a final document, a prospect that prompts last minute soul searching.

Two topics assume center stage: procedures for ratifying and amending the contract.

Friction materializes around “who will be asked to approve the new Constitution, and by what margin must it pass?”

Two of the most vocal Anti-Federalists, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts and Maryland’s Luther Martin, insist that approval must rest with the State Legislatures. But their pleas are beaten back after another strong Anti-Federalist, Virginia’s George Mason, speaks up.

Whither must we resort? To the people…It is of great moment that this doctrine be cherished as the basis of free government.

With Mason’s support, the assembly returns to the “Virginia Plan,” which proposes that special Conventions be held in each state involving representatives, elected by the people for the express purpose of debating and voting on the Constitution. As Madison writes, it must be backed…

By the supreme authority of the people themselves…the fountain of all power.

The focus now shifts to whether or not all thirteen states must ratify the new contract before it becomes the law of the land. While the rules of the Confederation require unanimity, many fear this will be impossible – especially since one state, Rhode Island, has refused to even show up in Philadelphia.

After some give and take, the requirement is set at 9 states needed for approval. This further inflames resistance from Gerry and Martin.

Gerry broadens his attack, insisting that, as it stands, the document is full of flaws, and that “amendments” are needed. He adds his doubts that Maryland will ever agree. This time George Mason takes his side, announcing his wish that…

Some points not yet decided should (be) brought to a decision before being compelled to give a final opinion on the Article. Should these points be improperly settled, (we need) another general convention.

Alexander Hamilton weighs in, supporting Gerry’s demand that the document be approved unanimously.

Edmund Randolph, author of the “Virginia Plan,” also supports Gerry’s call for amendments – as does Ben Franklin, who, surprisingly, offers a motion in favor of state conventions developing amendments to be brought back for approval to a second Convention.

For Madison and Washington, the notion of any lengthy delay in the start-up of a new functioning government is tantamount to failure. James Wilson shares their frustration in his admonition to the hall:

After spending four or five months…on the arduous task of forming a government for our country, we are ourselves at the close throwing insuperable obstacles in the way of its success.

Wilson’s sentiment prevails, and Franklin’s motion is tabled for the moment.

September 5 – 12, 1787

The Convention Moves Toward Summing Up

On September 5 the body names a “Committee Of Style and Arrangement” to assemble all of the decisions reached so far and draft a final Constitution, with a one week deadline.

The Committee is headed by Dr. William Johnson of Connecticut, graduate of Yale and Harvard, an honorary doctorate from Oxford, an accomplished lawyer, and current president of Kings (Columbia) College in New York. He is joined by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Gouvernor Morris and Rufus King, the later generally regarded as the finest orator in the nation.

As they labor on, several other issues are wrapped up.

A national capitol comprising 10 square miles of land is to be established at a site to be determined. It will not be a sovereign State, but rather administered by the Federal Congress.

Shifting Locations Of The Nation’s Capital

| Governing Periods | Timeframe | Locations |

| First Continental Congress | 9/5 – 10/24 1775 | Philadelphia |

| Second Continental Congress | 5/10/75 – 3/1/81 | Philadelphia, Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Phil. |

| Articles Of Confederation | 3/1/81 – Fall 1788 | Philadelphia, Princeton, Annapolis, Trenton, New York City |

| U.S. Constitution | 3/4/89 – 11/17/1800 | New York City, Philadelphia, Washington |

Foreigners may serve in Congress after living in America for either seven years (for the House) or nine years (for the Senate) – but the President must be native born.

The Executive, along with members of Congress and the judiciary will swear an oath to uphold the Constitution.

A small standing army will be allowed, even in time of peace — while state militias will continue to be relied on in case of war.

The definition of “treason” is resolved: engaging directly in war against the United States or giving aid and comfort to the enemy. Two witnesses to treasonous acts are required for conviction. Punishment for the crime will be determined by Congress, and confined to the traitor himself and not carried over to his offspring.

On September 12, Dr. Johnson’s Committee arrives in the hall with a final draft of the new Constitution.

James Madison acknowledges that authorship belongs mainly with Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania.

The finish given to the style and arrangement belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris.

The opening words of the document ring true to the spirit of the entire endeavor.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

It is “we the people” acting as one unified body who are declaring the form and substance by which they expect to be governed. It is the people who will decide, not the States acting like corporate entities.

The individual States will retain their sovereignty, but within specified boundaries. As Gouverneur Morris says:

When the powers of the national government clash with the states, then must the states concede.

Out of the countless Resolves presented to the Convention, Morris arrives at a final set of 7 Articles, each with sub-sections, codifying the three branches of government and declaring how the Constitution is to be ratified by the states and amended over time if need be.

September 15, 1787

The Constitution Is Approved Without A “Bill Of Rights”

Once again the persistent George Mason of Virginia is on his feet, this time asking that a Bill of Rights be added to the final document. He points out that eight state constitutions identify these rights, and that a committee could draft them in a few hours.

If prefaced with a bill of rights…it would give great quiet to the people.

The legal scholar, Wilson, rejects Mason’s plea, on the grounds that the Constitution deals with municipal laws, not “natural laws.”

Other opponents are less diplomatic in their criticisms.

Hearing about Mason’s call, the lexicographer and political observer, Noah Webster, cites the folly of trying to codify the rights of man. His sarcastic call goes out for a clause that…

Everybody shall, in good weather, hunt on his own land…that Congress shall never restrain any American from eating and drinking…or prevent him from lying on his left side…when fatigued by lying on his right.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina offers another sound “regional reason” to skip a bill of rights.

These generally begin that all men are by nature born free. We should make that declaration with very bad grace when a large part of our property consists in men who are actually born slaves.

Others insist that the Document itself, from start to finish, guarantees personal values and rights. When a vote is taken, Mason’s call for a Bill of Rights is voted down by a 10-0 margin.

The delegates want closure at the moment – and a full year will elapse before Mason’s wish is realized in Ten Amendments that finally codify many of America’s most cherished freedoms.

A vote is now taken on adopting the Constitution as written, with all states voting “aye.”

E pluribus unum. Out of many, one.

The thirteen sovereign states have become a new national Union.

September 17, 1787

The Delegates Sign The Constitution

After approving the draft, a calligrapher named Jacob Shallus is given the task of “engrossing” the text. He does so on four large pages (28” x 23”) of parchment, comprising some 4,000 words in total. A fifth page is left for signatures.

The document is ready for signing on Monday, September 17, as summer turns into autumn in Philadelphia.

Thirty-eight of the original 55 delegates are present.

After the new Constitution is read aloud, Benjamin Franklin is recognized for a speech delivered for him by his Pennsylvania colleague, James Wilson.

I confess there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment. But I consent, sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better and because I am not sure it is not the best. I cannot help expressing a wish that every member.. (vote) with me…to make manifest our unanimity.

With hope for unanimity in mind, Franklin offers a motion, written by Gouvernor Morris, that would allow any individual dissenters to sign the document under the banner of majority support by their state delegation.

Next comes a last second plea from Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts on behalf of expanding the size of the House by allocating one representative for every 30,000 rather than 40,000 state residents.

This suggestion prompts George Washington to speak for the first and only time during the Convention. His remarks are couched within his usual tone of humility. Madison records them as follows:

Although his situation had hitherto restrained him from offering his sentiments on questions depending in the House, and it might be thought ought now to impose silence on him, yet he could not forbear expressing his wish that the alteration proposed (by Gorham) might take place…since the smallness of the proportion of representatves had been considered by many members…an insufficient security for the rights and interests of the people.

With Washington’s backing, the change is approved, the result being a sizable jump from 51 to 68 total seats in the House when it finally convenes in 1789.

At this point members are given a final chance to say what they will.

It is with great sadness that Edmund Randolph announces he cannot sign the final document. His role all along has been critical, from presenting the “Virginia Plan” to authoring the Committee On Detail report. But now he declares that his duty as a Virginian is to refrain from endorsing the Constitution until he can hear directly from the people of his state.

Not surprisingly Randolph is joined by George Mason, whose opposition has been clear all along. Mason doesn’t speak on this day, but writes up three pages worth of objections, which he later shares with Washington. These focus on the erosion he senses in state sovereignty, and the absence of a bill of rights.

After Gouvernor Morris voices his support for the document and urges others, including Randolph, to follow, the third and final dissenter left in the room, Elbridge Gerry, has his say. The Massachusetts delegate finds the outcome still too divisive, and likely to lead on to civil war between factions in his own state.

Four others who oppose the Constitution have already departed: the two New Yorkers (Lansing and Yates) and two Marylanders (Luther Martin and John Mercer).

But September 17 belongs not to the dissenters, rather to the 35 other men present who have labored on behalf of a grand vision of government of the people, by the people and for the people.

Each in turn steps forward to sign, beginning with New Hampshire and working sequentially south to Georgia.

The Thirty-Nine Eventual Signers Of The Constitution

| States | Delegates |

| New Hampshire | Gilman, Langdon |

| Massachusetts | Gorham, King |

| Rhode Island | No delegates |

| Connecticut | Johnson, Sherman |

| New York | Hamilton |

| Pennsylvania | Clymer, Fitzsimons, Franklin, Ingersoll, Mifflin, G Morris, R Morris, Wilson |

| New Jersey | Brearly, Dayton, Livingston, Patterson |

| Delaware | Bassett, Bedford, Broom, Dickinson, Read |

| Maryland | Carroll, Jenifer, McHenry |

| Virginia | Blair, Madison, Washington |

| North Carolina | Blount, Spaight, Williamson |

| South Carolina | Butler, CC Pinckney, C Pinckney, Rutledge |

| Georgia | Baldwin, Few |

The grand Convention then closes, with delegates off for a celebratory dinner together at the City Tavern. Afterward, several reflect on the outcome.

Washington expresses amazement: “much to be wondered at…little short of a miracle.”

So does the South Carolinian “CC” Pinckney: “astonishingly pleased (that a government) so perfect could have been formed from such discordant and unpromising material.”

The delegate from New Hampshire, Nicholas Gilman, explains how it happened:

It was done by bargain and compromise…(testing) whether or no we shall become a respectable nation, or a people torn to pieces by intestine commotions, and rendered contemptible for ages.

From abroad, staunch Federalist John Adams and Anti-Federalist, Thomas Jefferson, both applaud, the latter wishing only for a bill of rights and term limits on the Executive.

Almost all agree that something amazing has just taken place in Philadelphia.

1787-1788

Five States Ratify Within The First Year

On October 27, 1787, Congress submits the Constitution to the States for ratification.

The bar for acceptance has been set at nine states, but no one is particularly comfortable about “imposing” the contract on holdouts. The unanimity Franklin lobbied for is deemed essential.

Proponents are well aware of the states most likely to balk at ratification, including a big three — Massachusetts, Virginia and New York – whose cumulative populations combined 40% of the nation’s total.

To promote acceptance, the strategy lies in “frontloading” the process in States more likely to vote “yes,” thereby putting pressure on the others to follow suit.

At the same time, a publicity campaign is mounted in the popular press. Philadelphia alone boasts over 100 newspapers in 1787, and scholars have pegged literacy at 90% in New England, a level surpassed at the time only in Scotland.

The campaign comes in the form of a series of 85 articles, titled The Federalist Papers. These are the work of three men: Alexander Hamilton, who authors 51 of the 85, James Madison with 26, John Jay with 5, the others being collaborations.

They are all published under the pseudonym of Publius, “friend of the people” a Roman aristocrat, who helped overthrow a corrupt monarchy in 509BC. Their content is intended to inform the public about the ideas within the new Constitution and reasons why it should be supported.

By January 9, 1788 these strategies are working, with five states voting approval by wide margins, mostly after less than a week of debate.

First Five States To Ratify The Constitution

| States | #Days | Date | Pre Vote | Final Vote | Key Delegates |

| Delaware | 3 | Dec 7, 1787 | 30-0 | 30-0 | Bedford |

| Pennsylvania | 23 | Dec 12, 1787 | 46-23 | 46-23 | Wilson |

| New Jersey | 7 | Dec 18, 1787 | 38-0 | 38-0 | Brearly |

| Georgia | 6 | Dec 31, 1787 | 29-0 | 26-0 | Few |

| Connecticut | 6 | Jan 9, 1788 | 128-40 | 128-40 | Sherman, Ellsworth, Johnson |

By July 26, 1788

Massachusetts, Virginia And New York Assure Passage

The first real test is in Massachusetts, where the 355 Convention delegates chosen are evenly divided with 177-178 “for and against” ratification, as they assemble. The debates extend over four weeks, with Rufus King and Nathaniel Gorham pitted against Anti-Federalists led by Sam Adams and Elbridge Gerry behind the scenes. The wild card here turns out to be Governor John Hancock, who is accused of tipping toward the “pro” side in exchange for promises of higher office in the new government. Ten votes switch sides and the Constitution is ratified by 187-168 – with an accompanying call for “amendments.”

Despite Luther Martin’s dire predictions, Maryland votes “aye” by a comfortable 63-11 margin. South Carolina follows, and when New Hampshire agrees on June 25, 1788, the nine-state target is achieved. Still all eyes remain focused on Virginia and New York.

Both Madison and Washington have been disappointed by the fact that only three of Virginia’s seven delegates signed their names to the Constitution. The venerable George Mason has refused, as has the sitting Governor, Edmund Randolph. The state also boasts two famous patriots – Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee – both outspoken critics of the new contract, and of Washington himself. The delegates go into the state convention with 84 tentatively pledge to vote “aye” and 84 pledged “nay.” After three weeks, five votes change hands and the Constitution is ratified. Ironically Edmund Randolph decides to lend his support, and plays an important role along the way.