Section #20 - Futile attempts to save the Union follow John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry

Chapter 247: A Congressional Investigation Of Harpers Ferry Solves Nothing

January 4, 1860

A Senate Committee Is Set Up To Investigate

As the House is arguing over electing a Speaker, the Democrat-controlled Senate turns immediately to investigating the events surrounding the Harpers Ferry raid.

A five-person panel is assigned the task, with James Mason as Chair:

Harpers Ferry Investigation Committee

| Senators | State | Party |

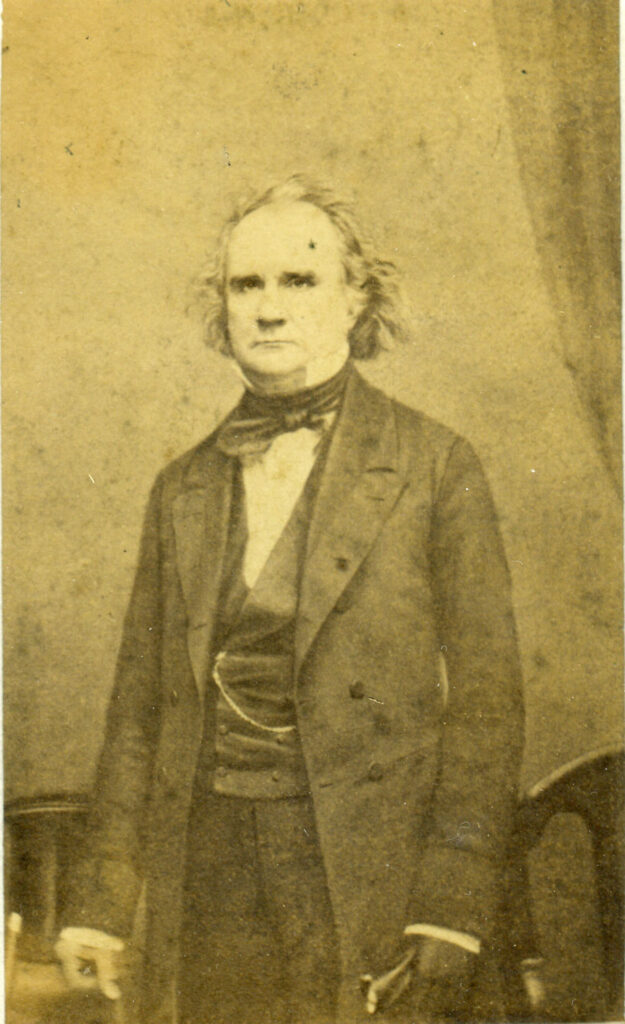

| Jacob Collamer | Vermont | Republican |

| Jefferson Davis | Mississippi | Democrat |

| James Doolittle | Wisconsin | Republican |

| Graham Fitch | Indiana | Democrat |

| James Mason | Virginia | Democrat |

Four questions are front and center as the effort begins:

- The facts in relation to the invasion and seizure of the armory and arsenal at Harper’s Ferry.

- Whether it was in pursuance of an organization, and the nature and purpose thereof.

- The arms and munitions there possessed by the insurgents, and where and how obtained.

- Were any citizens, not present, implicated in, or accessory thereto, by contributions of arms, money, ammunition, or otherwise.

June 15, 1860

The Findings Have Little Impact In Congress

The effort runs all the way to June 15, 1860 and includes testimony from 32 witnesses – albeit missing key figures like Hugh Forbes, four of the Secret Six, John Brown Jr., and Frederick Douglass.

Two final documents are issued: a majority report written by Mason and a minority version from Collamer, with both fairly anodyne in nature.

The facts and timeline surrounding the raid are covered in detail – as are Brown’s efforts to establish a Provisional Government at the Chatham, Ontario convention, and the origin and shipment of the weapons used.

When it comes to co-conspirators, George Stearns and Samuel Howe admit to dealing with Brown, but insist they thought their support was directed at Kansas and not Virginia.

As to proposed to follow up actions by Congress, Mason concludes that:

The committee, after much consideration, is not prepared to suggest any legislation, which, in their opinion, would be adequate to prevent like occurrences in the future….(but) would earnestly recommend that provision should be made by the executive, or, if necessary, by law, to keep under adequate military guard the public armories and arsenals of the United States, in some way after the manner now practiced at the navy-yards and forts.

The minority report written by Jacob Collamer rejects any conjecture that Free State abolitionists provoked Brown’s attack, while announcing that as long as Southerners insist that slavery is a divinely inspired and humanizing institution, they need to be prepared for further debate in Congress from those who disagree.

So long as Congress, in the exercise of its power over the Territories, is invoked to exert it to extend, perpetuate, or protect the institution of slavery therein…so long must its moral, political, and social character and effects be unavoidably involved in congressional discussion… So long as slavery is claimed before the world as a highly benignant, elevating, and humanizing institution, and as having Divine approbation, it will receive at the hands of the moralist, civilian, and theologian the most free and unflinching discussion; nor should its vindicators wince in the combat which their claims invite.

In the end, the Mason Committee proves anti-climactic, adding little to what was already known about the Harpers Ferry raid, and certainly not healing the sectional wounds it caused.