Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Chapter 10: The Plight Of Those Enslaved

1790

Slavery Continues to Wither Away In The North

As of 1790, there are some 698,000 enslaved people living in America alongside another 57,000 who are “freed men and women.”

Black Population In America In 1790

| Total | Enslaved | Freed |

| 755,000 | 698,000 | 57,000 |

But by that time, six of the eight Northern states have already banned slavery.

Dates Of Northern States Bans On Slavery

| Year | State | Terms |

| 1777 | Vermont | Constitution bans immediately |

| 1780 | Penn | Current slaves kept for life, but their children are free |

| 1783 | NH | Current gradually freed; children born free |

| 1783 | Mass | All freed immediately |

| 1784 | Conn | All 25+ years old and new borns freed immediately |

| 1784 | RI | All freed immediately |

| 1799 | NY | Current freed in 1827; children born free |

| 1804 | NJ | Current slaves kept for life, but their children are free |

The result being that only 40,000 slaves remain up North, with the majority of them in New York and New Jersey.

The Black Population In The Eight Northeastern States In 1790

| NY | Pa | NJ | Conn | Mass | RI | VT | NH | Total | |

| Slaves | 21,193 | 3,707 | 11,423 | 2,648 | 0 | 958 | 0 | 157 | 40,086 |

| Free Black People | 4,785 | 6,567 | 2,762 | 2,924 | 5,463 | 3,397 | 271 | 631 | 26,800 |

| Total | 25,978 | 10,274 | 14,185 | 5,572 | 5,463 | 4,355 | 271 | 788 | 66,886 |

| Tot Pop | 340,120 | 434,373 | 184,139 | 237,846 | 378,787 | 68,825 | 85,425 | 141,885 | 1,871,400 |

The end of slavery in the region is reflected by the journey of the roughly 2,700 slaves still remaining in Connecticut. By 1774, some 6500 slaves remain, with the Puritans justifying the practice based on various Bible verses and on the notion that captivity had enabled the enslaved people to learn about Christianity.

To control these slaves, Connecticut passes “Black Codes” in 1730 that outline a series of “whipping offenses:” being outside after 9PM without a signed pass; drinking liquor or selling goods without written permission; disturbing the peace or threatening a white person.

The Puritans tend to treat their slaves in a paternalistic fashion. Many act as household servants rather than field hands, and they are allowed to attend church services with their owners, albeit sitting in segregated pews. Some black children are also allowed to attend local schools.

While voluntary “manumission” occurs from time to time, the formal movement away from slavery begins in Connecticut in 1774 with a ban on the importation of Africans, in response to complaints from white laborers looking for work. When the war with England breaks out in 1776, some black people join the Continental Army, fight in integrated units, and gain their freedom as a result of their service. Others find ways to accumulate the money needed to purchase freedom from their owners.

Then, in 1784, a Connecticut state law grants freedom at age 25 years to all future newborn slaves, and by the 1820 census, only 97 slaves are remaining.

Meanwhile, in 1790, the picture across the South is radically different. The region accounts for 94% of all those in bondage, and in four states, slaves make up over one-third of the state’s total population.

The Black Population In The Six Southern States In 1790

| Total | Virginia | S. Carolina | Maryland | N. Carolina | Georgia | Delaware | |

| Total (000) | 658 | 293 | 115 | 108 | 104 | 29 | 9 |

| % Of State Pop | 18% | 39% | 43% | 32% | 26% | 35% | 15% |

1790

Jefferson’s Stereotypical Views Of His Slaves

(1743-1826)

By 1790 native Africans have lived among white Americans for well over 150 years. The practice of slavery has gradually withered away in the North and the total black population there has leveled off at around 67,000, with some 27,000 living as “manumitted” or free men. Not so in the South, where upwards of 650,000 slaves are critical to the economic prosperity of the region.

Despite these different outcomes, what is common among white men both North and South is a stereotypical view of all black people as an inferior “sub species” to be contained and controlled and feared.

No one articulates these prejudices more clearly than Thomas Jefferson, the Squire of the Monticello Plantation. They are best captured in his 1785 book, Notes on the State of Virginia where, in clinical fashion, he discusses the differences between black people and white people, and why these will never be reconciled.

In memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid;

They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation.

Black men prefer white women over their own, just as orangutans prefer black women over their own.

They secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour.

Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them.

Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved.

In imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.

Apart from their lack of respect for property laws, which is understandable, there are…numerous instances of the most rigid integrity, of benevolence, gratitude, and unshaken fidelity.

Jefferson goes on to wonder what could explain the differences between himself and the over 100 African slaves who surround him on a daily basis.

In the end, all he can conclude is that, perhaps, black people represent a different species from white people.

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind…

This unfortunate difference of colour, and perhaps of faculty, is a powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people.

Herein lies the basis for much of the anti-black racism that infects the white population, both South and North. It argues that the Africans are “a distinct race” and “inferior in both body and mind.” In other words, they are sub-human beings by no means created equal, and incapable of ever rising beyond their present station.

The “American Dream” is for white men, not for the black people. So saith the man who will serve as America’s third president.

1619 and Forward

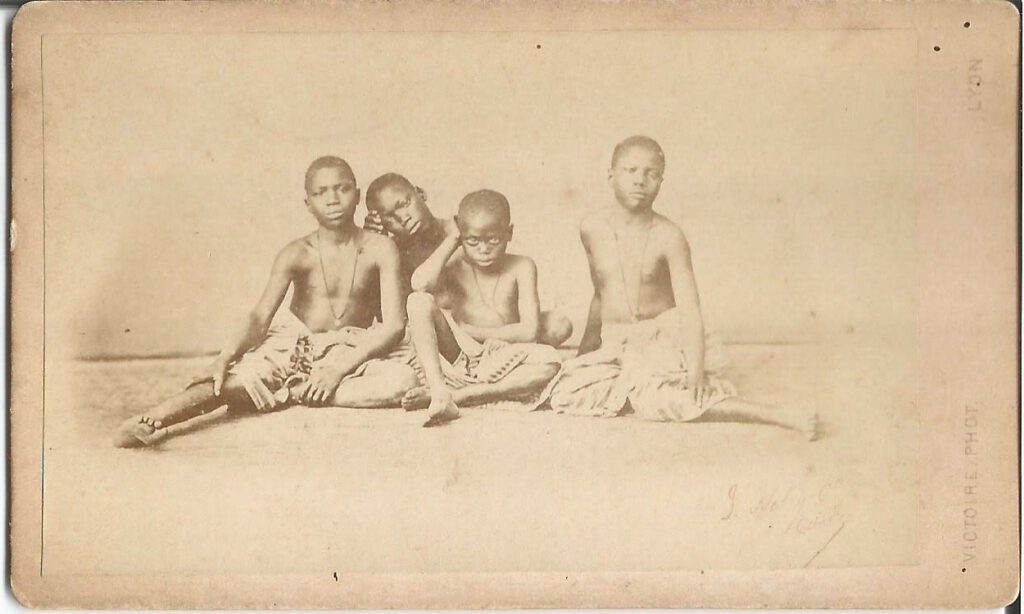

The Daily Suffering Of Those Enslaved In The South

While white American are striving to get ahead in 1790, enslaved people are left simply trying to survive.

Standing in bug and worm infested dirt or mud or ankle deep water to cultivate rice, tobacco or cotton becomes their lot. It is punishing labor and intensely monotonous. It is marked by fear at any moment of the lash, delivered by a displeased or arbitrarily sadistic overseer. It is also endless. The only way out is death, and death is all around, in the faces of the young and the old, all accelerated by meager rations, run-down living quarters and flimsy attire.

Their later recorded testimonials tell of hard lives marked by back-breaking labor, gnawing hunger, physical punishment and constant fear of being uprooted from the solace offered by their families and fellow captives.

In 1790, one in every four North Carolinians are slaves. Here are their stories;

Moses Grandy of Camden, NC:

Daily life for a slave in North Carolina was incredibly difficult. Slaves, especially those in the field, worked from sunrise until sunset. Even small children and the elderly were not exempt from these long work hours. Slaves were generally allowed a day off on Sunday, and on infrequent holidays such as Christmas or the Fourth of July.

I was next with Mr. Enoch Sawyer of Camden county: my business was to keep ferry, and do other odd work. It was cruel living; we had not near enough of either victuals or clothes; I was half starved for half my time. I have often ground the husks of Indian corn over again in a hand-mill, for the chance of getting something to eat out of it, which the former grinding had left. In severe frosts, I was compelled to go into the fields and woods to work, with my naked feet cracked and bleeding from extreme cold: to warm them, I used to rouse an ox or hog, and stand on the place where it had lain. I was at that place three years, and very long years they seemed to me.

Moses Roper of Caswell, NC:

At this time I was quite a small boy, and was sold to Mr. Hodge, a negro trader. Here I began to enter into hardships. After travelling several hundred miles, Mr. Hodge sold me to Mr. Gooch, the cotton planter, Cashaw county, South Carolina; he purchased me at a town called Liberty Hill, about three miles from his home. As soon as he got home, he immediately put me on his cotton plantation to work, and put me under overseers, gave me allowance of meat and bread with the other slaves, which was not half enough for me to live upon, and very laborious work. Here my heart was almost broke with grief at leaving my fellow slaves. Mr. Gooch did not mind my grief, for he flogged me nearly every day, and very severely.

Harriet Jacobs of Edenton, NC:

Why does the slave ever love? Why allow the tendrils of the heart to twine around objects which may at any moment be wrenched away by the hand of violence? …I did not reason thus when I was a young girl. Youth will be youth. I loved, and I indulged the hope that the dark clouds around me would turn out a bright lining. I forgot that in the land of my birth the shadows are too dense for light to penetrate.

There was in the neighborhood a young colored carpenter; a free born man. We had been well acquainted in childhood, and frequently met together afterwards. We became mutually attached, and he proposed to marry me. I loved him with all the ardor of a young girl’s first love. But when I reflected that I was a slave, and that the laws gave no sanction to the marriage of such, my heart sank within me. My lover wanted to buy me; but I knew that Dr. Flint was too willful and arbitrary a man to consent to that arrangement.

James Curry of Person County, NC:

During their few hours of free time, most slaves performed their own personal work. The diet supplied by slaveholders was generally poor, and slaves often supplemented it by tending small plots of land or fishing. Many slave owners did not provide adequate clothing, and slave mothers often worked to clothe their families at night after long days of labor. One visitor to colonial North Carolina wrote that slaveholders rarely gave their slaves meat or fish, and that he witnessed many slaves wearing only rags. Although there were exceptions, the prevailing attitude among slave owners was to allot their slaves the bare minimum of food and clothing; anything beyond that was up to the slaves to acquire during their very limited time away from work.

In the following spring, my master bought about one hundred yards of coarse tow and cotton, which he distributed among the slaves. After this, he provided no clothing for any of his slaves, except that I have known him in a few instances to give a pair of thoroughly worn-out pantaloons to one. They worked in the night upon their little patches of ground, raising tobacco and food for hogs, which they were allowed to keep, and thus obtained clothes for themselves. These patches of ground were little spots, they were allowed to clear in the woods, or cultivate upon the barrens, and after they got them nicely cleared, and under good cultivation, the master took them away, and after they got them nicely cleared, and under good cultivation, the master took them away, and the next year they must take other uncultivated spots for themselves.