Section #1 - America’s years as a British Colony end with The Revolutionary War

Chapter 4: America’s Foundational Churches Take Hold In The Colonies

1607 Forward

The Colonists Are Dedicated Church-Goers

One thing that bonds the early American colonists is their church-going traditions and their focus on securing eternal salvation.

For the vast majority of those who arrive in Virginia in 1607 and Massachusetts in 1620 this means a commitment to the Protestant religion.

Some are conservative Anglicans, who will assume an American identity as the Episcopalian Church. Their doctrines remain consistent with King Henry VIII’s patchwork amalgamation of Catholicism and Protestant reform, and their governance is clearly top-down, with authority over all church matters resting with a clerical hierarchy. The Anglican liturgy mimics the old world Mass, and its tonality is formal.

Followers are heavily skewed toward the Southern colonies.

Others reject what they regard as corrupt practices within the Church of England and intend to go their own way in the new world. Included here are the Puritans and Lutherans who tend to evolve into the Congregational Church. It eliminates the clerical hierarchy and, consistent with democratic impulses, places authority for religious practices in the hands of the membership. Its influence is centered in New England.

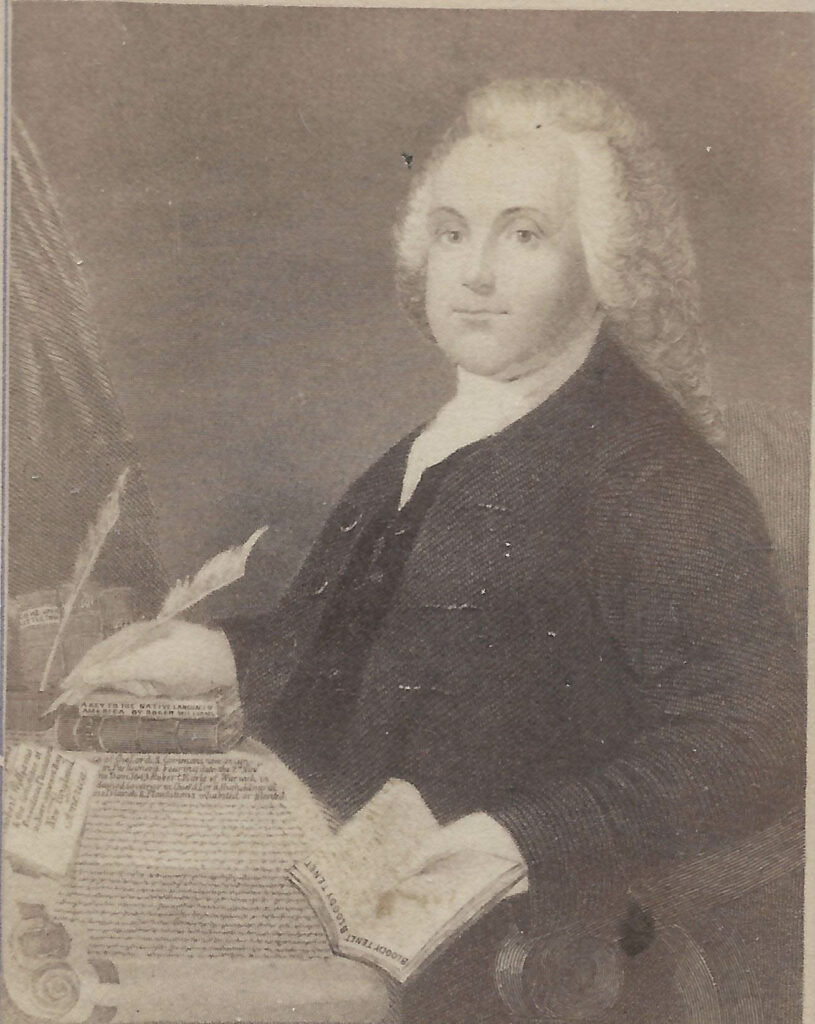

Like the Congregationalists, Baptists embrace basic Calvinist tenets: salvation through faith alone, predestination, the Bible as the word of God dictating the right path, authority in the hands of the congregation rather than a clergy. What distinguishes them, however, is a belief that the act of baptism should be reserved for adults, not newborns, as a symbol of their studied commitment to entering the church. After its founding by Roger Williams in 1632, the Baptist Church spreads beyond Rhode Island, especially into the South.

Another sect, the Society of Friends, or Quakers (who “tremble” at the name of God) arrive in 1656 and take up residence in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their belief is that everyman can attain salvation by listening to and obeying an “Inner Light” which guides their path toward moral perfection. They have no formal clergy and their church services are “spontaneous” and marked by individual testimonials. In 1681 William Penn founds the Pennsylvania Colony as a “home for persecuted Quakers.” From then on they play a central role in opposing slavery.

The Presbyterian Church is founded by the Scottish preacher, John Knox (1505-1572) and its theological roots are linked to John Calvin (1509-1564). But church governance here falls to a body of “elders” rather than to the members of the congregation as a whole. Hence its name, derived from the Greek word for elders – “presbyteros.” The Presbyterian Church appears in America around 1706, accompanying immigrants from Scotland. It takes hold mainly in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and the western territories.

During the 1830’s “new school and old school” Presbyterians will divide, with the former evolving into Unitarians.

These four important sects – Episcopalians, Congregationalists, Baptist and Quakers – will be joined later on by Methodists and then a host of other Protestant off-shoots which emerge around the “Second Great Awakening” of the 1830’s.

The Catholic Church also finds a home within the colonies. It originates in the Spanish “missions” scattered from Florida west to New Orleans and up the Mississippi River. Then in 1632 England’s Catholic King Charles I cedes the Colony of Maryland to his former Secretary of State, Lord Baltimore. Despite this, the religious ill will evident in Europe carries over to the colonies, with Catholics accused of being loyal to the Pope in Rome instead of the American government.

By 1730 each religious denomination is settling into place in the colonies, some holding on to traditional church hierarchies and liturgy, others breaking away toward new options.

At this point the Enlightenment spirit strikes the American church scene.

1730’s

The “First Great Awakening” Sparks Evangelical Christianity

Along with the Enlightenment comes a growing sense that by relying on their own capacity to reason, individuals can shape their personal destinies, their societies, and their government.

This is a transformative idea, and its impact is felt throughout colonial America in the 18th century.

Within the religious realm, the enlightenment spirit is reflected in what becomes known as the “First Great Awakening” which begins in the 1730’s. The embodiment of this movement is an otherwise conservative Puritan minister, Reverend Jonathan Edwards, preaching in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Edwards is born in 1703 in East Windsor, Connecticut, a single son surrounded by ten sibling sisters. The family survives on modest means, a minister father eking out spare income by tutoring boys prior to entering college. One such boy is the son, Jonathan, a precocious student who enters Yale at age 13 and graduates as valedictorian of his class in 1720. Young Edwards is intensely disciplined throughout his life, studying and writing every day for up to 13 hours, taking time out only when other duties demand his attention. He is naturally drawn to the sciences, but sees in them a framework for man that is divinely inspired. His life will be devoted to faith not Deism.

He serves briefly as a novice pastor in 1722 before returning to Yale as a theological tutor, affirming his strict adherence to traditional Calvinist principles. His personal life is ascetic, marked by self-imposed control over his time, his diet, his study and contemplation, his search for the moral perfection expected of those committed to thePuritan theology.

The way to Heaven is ascending; we must be content to travel uphill, though it be hard and tiresome and contrary to the natural bias of our flesh.

Edwards is formally ordained as a Congregationalist minister in 1727, and marries the daughter of the clergyman James Pierpont, founder of Yale.

By 1732 his spiritual journey comes up against the Arminian movement, named after the Dutch Reformed Church theologian, Jacob Arminius (1560-1609). It posits a profoundly different view about eternal salvation, and one that will be adopted by many American sects over time:

| Founder | Belief About Eternal Salvation |

| Calvin | “Pre-destination.” Only those who are chosen by God’s grace alone to be among “the elect” are saved. |

| Arminius | “Free will.” All persons are capable of being saved if they choose to lead their lives in accordance with Christian principles and practices. |

As the pure Calvinist, Edwards comes down on the side of God as sole arbiter of salvation. In his most famous sermon, “Sinners In The Hands Of An Angry God,” delivered in 1741, he exhibits his “fire and brimstone” fervor:

O sinner! Consider the fearful danger you are in: it is a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath, that you are held over in the hand of that God, whose wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you, as against many of the damned in hell.

But what distinguished Edwards as the “father of the First Great Awakening” is not his theology but rather the manner of preaching he adopts at his “revival meetings” in Northampton.

These center on “conversion experiences” whereby members of the congregation publicly pledge their lives to Christ. Edwards describes one such event in 1741:

In the month of May, 1741, a sermon was preached to a company, at a private house. One or two persons were so greatly affected with a sense of the glory of divine things and the infinite importance of the things of eternity that…it had a visible effect upon their bodies….The affection was quickly propagated throughout the room (with) many of the young people overcome…with admiration, love, joy and praise and compassion (while) others were overcome with distress about their sinful and miserable state and condition. The whole room was full of nothing but outcries, faintings and the like. The meeting continued for some hours, the time being spent in prayer, singing, counseling, and conferring. There seemed to be a consequent happy effect on many people and on the state of religion in the town.

Suddenly, with Edwards, the preacher is no longer held above and apart from his flock, but instead comes down from the pulpit to spontaneously share and explore religious feelings and experiences.

Thus “Evangelical Christianity” – the belief that all men can be “re-born” by openly embracing the literal word of God in the Bible –begins to assert itself in America.

Needless to say, Edward’s traditional colleagues are shocked and dismayed by the “revival meetings,” which may draw up to 500 people, extend over several days, and dominate a town’s entire life while they last. On rare occasions they are also followed by suicides, as some attendees leave convinced they are among the doomed.

The effect is that by 1751, Jonathan Edwards falls out of favor with the forces around him, and is driven out of his Northampton Church. He lives eight more years, dying one month after being named President of the College of New Jersey (Princeton).

1730’s

This Evangelical spirit also manifests itself in the Methodist Church, which comes to America in 1736.

The sect is founded by the English cleric, John Wesley, who insists throughout his life that its roots are firmly in the Anglican tradition – hence its followers are often called Methodist Episcopalians.

The church tenets are worked out at Oxford University around 1730 by Wesley, his younger brother William, and one George Whitefield. Together they start a prayer group on campus, the “Holy Club,” which is so disciplined in its practice of piety that fellow students cast them as “The Oxford Methodists.” And the nickname sticks.

Unlike his brother and Whitefield – both staunch Calvinists – John Wesley is drawn toward Arminianism, with its promise that all men can be saved by trying to live a life of “moral perfection.”

For Wesley a signal of “perfection” lies not only in worshipping Christ, but also engaging in “reform missions” aimed at correcting injustices and supporting those in need.

To rally people toward these ends, Wesley embraces the “Evangelical revival meetings” currently popularized by Edwards.

In February 1736, John Wesley sails to America, eager to hold his revivals in the Georgia colony, especially among poor whites and various Indian tribes. His stay, however, lasts just under a year, and he regards it as a total failure.

After Wesley returns to London, his 23 year old colleague, George Whitefield follows him to Georgia in 1737.

Whitefield proves to be much more adept than the reserved Wesley with the open-air context – probably a reflection of his love for theater and for acting out Bible stories as a youth. He travels broadly in America, even preaching in 1739 alongside Edwards in Northampton. The colonial editor and inventor, Benjamin Franklin befriends him in Philadelphia and publishes several of his sermons in his newspaper. He also notes the positive effects of his ministry on the local community.

Wonderful…change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem’d as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro’ the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

The Reverend George Whitefield will make thirteen Atlantic crossing back and forth to England, before dying in 1770 in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

John Wesley survives Whitefield by two more decades. During that time he faces many challenges from the Anglican Church hierarchy. But he forever moves forward to establish his Methodist Church.

His beliefs will have great impact on mainstream religious development in America, especially the conviction that all men can achieve salvation, and that the proper path lies in studying God’s words in the Bible and in completing soul-saving “missions.”

Over time, Methodists will outnumber all other sects in terms of membership.

It will also play a pivotal role within the black community after a bishop named James Varick opens the first African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1721, located in New York City. From there, the “AME Church” provides a safe harbor and much needed support for blacks trying to survive and become assimilated.

1688 Forward

Early Church Opposition To Slavery Is Muted

Despite the professed interest in salvation, America’s churches are generally silent when it comes to addressing chattel slavery in the land.

The one institutional exception here is the Society of Friends in Pennsylvania. In 1688, a settler named Francis Pastorious submits the “Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery” at his local meeting, basing his argument simply on the Bible’s Golden Rule admonition.

Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law.

The cause is picked up in 1743 by John Woolman, a New Jersey Quaker, who resolves to “purify himself from the sin of slavery.” He publishes an anti-slavery pamphlet, Some Considerations on the Keeping of Slaves, and completes over thirty missionary tours from New England to the Carolinas, preaching in support of abolition.

Years later, Woolman’s personal crusade will make at least one key convert, Benjamin Lundy, an Ohio Quaker who, in the 1830’s, will pass the torch on to the towering champion of abolition, William Lloyd Garrison.

Quakers also lead the way in establishing a formal organization to oppose slavery. The Pennsylvania Society for the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held In Bondage is founded in 1775, with support over time from two “natural law” Deists, Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin.

In 1747, Jonathan Mayhew, minister of the West Church in Boston, preaches against a host of moral injustices, and sets the stage for the creation in the 1820’s of the Unitarian Church, and its on-going crusade against slavery.

In 1774 the First Baptist Church of Petersburg, Va, opens its doors to a black congregation and ministers – to be followed in 1777 by the First African Baptist Church of Savannah, founded by a former slave, and in 1801 by the First Baptist Church of Columbia, SC. At first some church’s missionaries also call for the end of slavery and equality of all men, while encouraging blacks to become both members and preachers. But this aggressive stance becomes muted over time, as Baptists try to extend their membership with Southern whites, many of whom are slave owners.

Within the emerging Methodist Church, John Wesley takes aim at slavery in his quest to achieve “Christian Perfection” through missionary work. His fervor here is evident in his 1774 tract, Thoughts Upon Slavery, as he rhetorically questions a slave trader’s humanity.

Are you a man? Than you should have a human heart. But have you indeed? What is your heart made of? Is there no such principle as Compassion there? Do you never feel another’s pain? Have you no Sympathy? No sense of human woe? No pity for the miserable?

When you saw the flowing eyes, the heaving breasts, or the bleeding sides and tortured limbs of your fellow-creatures, were you a stone, or a brute? Did you look upon them with the eyes of the tiger?

When you squeezed the agonizing creatures down in the ships, or when you threw their poor mangled remains into the sea, had you no relenting? Did not one tear drop from your eye, one sigh escape from your breast?

Do you feel no relenting now?

If you do not, you must go on, till the measure of your iniquities is full. Then will the Great God deal with You, as you have dealt with them, and require all their blood at your hands.

The Presbyterians are largely content to stay away from the issue early on — although synods in New York and Pennsylvania do file anti-slavery petitions.

Within the Anglican and Catholic churches, the record on colonial slavery suggests the same kind of institutional indifference evident across the mainstream Protestant sects.