Section #6 - The Second Religious Awakening sparks early moral concerns about slavery

Chapter 53: A Second Great Religious Awakening Sweeps Across America

1820-1840

A Finally Secure Nation Looks Inward For Guidance

The Monroe and Adams presidencies mark the first time in American history where the nation feels genuinely secure about its ability to withstand threats of war and invasion from abroad. The British have been twice beaten, and the specter of Napoleon is also gone. At long last, fortress America is safe.

What follows from this is a remarkable period of reflection, which takes hold of the public conscience between 1820 and 1840. It resurrects the deeply religious origins of the early colonial period and causes common men and women to step back from their daily toil and examine progress made toward the visions announced by their ancestors – namely, the creation of a virtuous society, the “shining city on a hill,” and their own personal efforts to achieve personal salvation.

The result is a “moral reawakening” that harkens back to the colonist’s original flight from England — and eventually lead to an Evangelical movements that will gradually reform the contemporary social fabric.

To a large extent, the 17th century voyagers to America were Protestant religious zealots, “puritans” of one form or another, seeking to escape the “corruptions” they associated with the established Anglican Church, and find their own path to righteousness and eternal life.

In the First Great Awakening of the 1730’s their quest leads to the formation of a wide range of new sects – Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Methodists – joining the already established Puritan, Anglican, Quaker and Baptist churches. During the Enlightenment period, non traditional Deists (“a religion of reason”) appear, along with small pockets of immigrant Catholics and Jews.

But still America remains as congenitally restless over its churches as it is over its government.

Much of the ongoing religious inquiry originates within the walls of America’s early universities and seminaries, whose prospective ministers engage in lively theological debates.

American Universities Founded By Churches

| Name | Year | Church Affiliation |

| Harvard | 1636 | Congregationalist |

| William & Mary | 1693 | Church of England |

| Yale | 1701 | Congregationalist |

| Princeton | 1746 | Presbyterian |

| Columbia | 1754 | Church of England |

| Penn | 1757 | Anglican/Methodists |

| Brown | 1764 | Baptist |

| Rutgers | 1766 | Dutch Reformed |

| Dartmouth | 1769 | Congregationalist |

Some of these relate to matters of liturgy and doctrine; some question the authority of a clerical hierarchy to set rules for their laymen; others seek to fundamentally alter the ways in which preachers interact with their congregations in the search for redemption and salvation.

Taken together they lead on to a Second Great Religious Awakening which sweeps across America between 1820 and 1840.

1820-1840

An Evangelical Spirit Takes Root

The Second Great Awakening mirrors the fervency brought to bear by the great Puritan preacher, Jonathan Edwards. It sounds an Evangelical message that will henceforth become a part of America’s religious landscape:

The good news promise of eternal salvation for sinners who adopt Jesus Christ as their savior.

In tenor, this awakening is much “gentler” than its predecessor. It shifts away from the harsh determinism of Calvin, where each man is “elected by God” at birth to be saved or damned, and nothing they can do will alter their destiny. Instead it embraces the “Arminian” conviction – proposed by the 16th century Dutch Reformed theologian Jacob Arminius – that every man can be saved by exercising his own “free will” to live in accord with the virtues set out by Jesus Christ.

This new message is delivered less from the elevated pulpit in solemn church services than in open air tent meetings where Evangelical ministers can wander among the masses and lay their hands on those coming forth to join the crusade.

The Word to be shared at these “revivalist events” comes directly from “the good book” – the King James Bible – which is to be read by each person and interpreted into a personal agenda that will lead on to salvation.

These individual agendas become “causes” – and, as such, they take on great meaning for those making their commitments. As in the Biblical book of John 12;27:

But for this cause, came I, unto this hour.

The central unifying cause within the Second Awakening movement lies in creating a more virtuous society for the benefit of all citizens.

In helping to save others, the Evangelicals believe they are saving themselves.

1825 Forward

The Awakening Is Led By The Preacher, Charles Grandison Finney

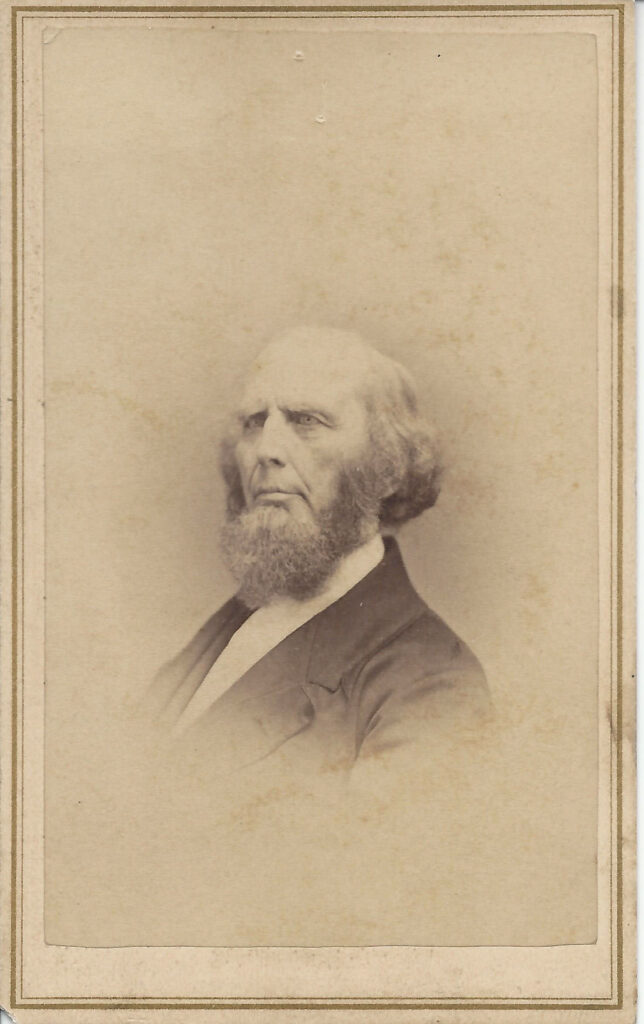

Of all the clergymen who propel the Second Awakening none has greater influence than the Reverend Charles Grandison Finney.

Finney is born into a farming family in Warren, Connecticut, in 1792, the youngest of 15 children. As a youth he dabbles in various academic interests before deciding to apprentice as a lawyer. He is engaged in the profession in 1821, when he happens to attend a religious revival meeting in the town of Adams, New York – and undergoes a spiritual transformation.

The Holy Spirit descended upon me in a manner that seemed to go through me, body and soul. I could feel the impression, like a wave of electricity, going through and through me. Indeed it seemed to come in waves of liquid love, for I could not express it in any other way. It seemed like the very breath of God. I can remember distinctly that it seemed to fan me, like immense wings. No words can express the wonderful love that was spread abroad in my heart.

Finney has found his calling, and he signs on as an apprentice to George Gale, a Presbyterian minister, who tries, unsuccessfully, to have him enroll in a theological seminary. Despite resistance to formal training, he is finally ordained in 1824, and sets off to spread the word of God, beginning in the Oneida county region of central New York State around the towns of Utica, Rome and Syracuse.

What distinguishes Finney from other clergymen is his “preaching style.”

At 6’3” tall and with piercing eyes, he stands in front of his audience and speaks to them in plain terms.

He is not interested in expounding on the intellectual intricacies of church doctrine – rather on seeking immediate converts to Christ among those in his presence. He does so by offering them a choice.

On one hand, to continue living as a sinner in the City of Man, and facing the eternal fire and brimstone punishments decreed by the traditional Calvinists. On the other, to cross over to the Kingdom of God and a future of virtuous behavior and eternal salvation and joy.

Furthermore he assures them that the power to choose lies entirely in their hands.

“Election” is not pre-determined. It is open to all who embrace the “indwelling spirit” of Christ that lives inside each of them. All they need to do is step forward right now to make their commitment to be saved.

After several days of near continuous preaching, a groundswell of emotion – often marked by apparent trances, swoons and convulsions — dominates these revival meetings. All leading to the denouement, the moment of conversion, with Finney calling out attendees by name, one after another, and asking them to come forward to declare their rebirth in Christ.

In another break with precedent, his call extends to women – whose role in church and social matters has been one of silence and conformity. Instead he asks women to speak up, to share their beliefs and feelings, to become full participants in the cause. Over time, the “voice of women” he encourages will play a vital role in a host of social reforms in America.

As the legions of Finney converts grows, both his theological tenets and his “preaching style” are questioned by the orthodox Protestant clergy of New England, most notably Lyman Beecher, the Yale-educated minister who favors the traditional Calvinist brand of Presbyterianism..

But Finney survives the challenges and expands his reach eastward into Wilmington, New York city, Philadelphia and, most notably, Rochester – where his revival meetings would shut down the entire town. Even Beecher is amazed. He concludes that the summer meetings of 1831 in Rochester are:

The greatest work of God, and the greatest revival of religion, that the world has ever seen in so short a time.

Other clergymen liken Finney’s effects to a religious prairie fire, and, after he departs the towns of western New York state, they are forever known as the “burnt over district,” signaling no souls left to be saved.

In 1835 Finney moves his home base to the recently founded Oberlin Collegiate Institute in Ohio, where, over the next 40 years, he builds the school into a beacon of light in support of “perfecting” man and society. During his first year, he convinces Oberlin to become the first college in the U.S. to admit blacks. He serves as President of the college from 1851 to 1866 and remains active there until his death in 1875.

Finney’s legacy, however, goes far beyond revival meetings and Oberlin College to the reform works carried out by his converts. As was the case with the Methodists Wesley and Whitehurst in the 1730’s, Finney’s intent is to encourage those reborn in Christ to undertake personal missions – in support of temperance, caring for the poor, prison reforms, child labor laws, equal treatment for women, and ending slavery in America.

1820 Forward

Unitarians Join The Call For Social Reform

Others catch the revivalist spirit prompting a host of uniquely American religious movements, some founded by clerics and others by laypeople, to spring up.

One that flourishes over time is the Unitarian Church.

The Church traces its roots to various Enlightenment thinkers in mid-16th century England and eastern Europe who dissent from fundamental tenets of both the Catholic and the Protestant churches.

Their most dramatic dissent focuses on the very “nature of God” – arguing that He is “one indivisible entity” rather than the three-person construct of the Trinity. In turn, Jesus Christ becomes a symbol for them of a life of perfect virtue to which all men should aspire – but not of “divinity itself,” as taught in traditional Christianity.

This belief in the unity of God gives the church its name.

The epicenter of the Unitarian movement in America becomes King’s Chapel Church in Boston where, in 1785, the Episcopalian minister, James Freeman, begins to preach some of its core beliefs, adopted during his study at Harvard Divinity school.

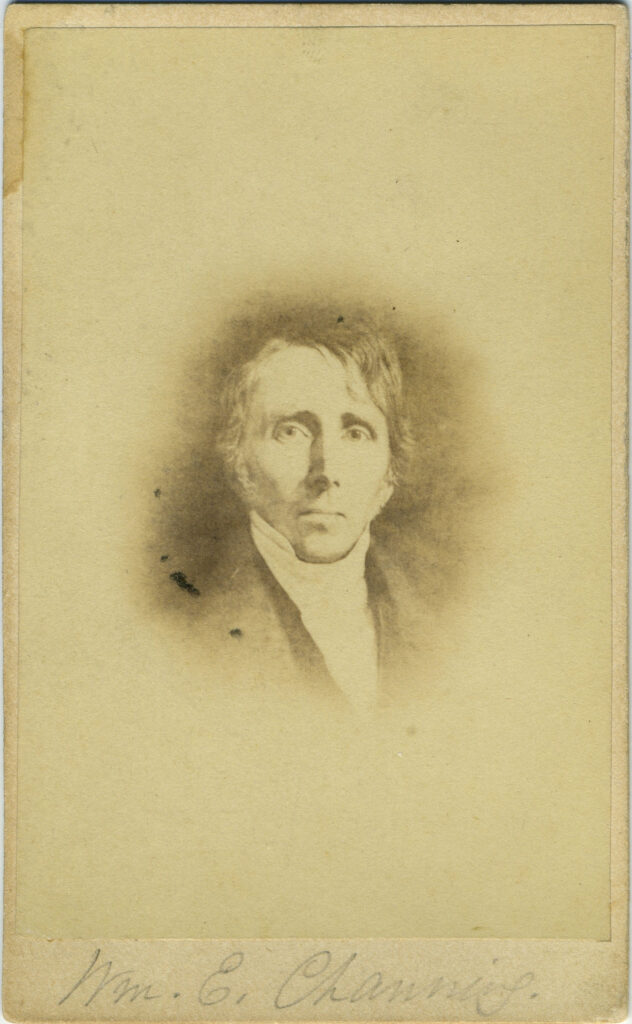

It is not, however, until 1819 that another Harvard graduate, William Ellery Channing, fully codifies the Unitarian canon.

It rejects the Calvinist notions of original sin and pre-destination of the elect in favor of an Arminian-like insistence on free will, and the potential for salvation of all who lead a life of virtue, like Christ. (Although one branch, the Universalists, posit that an infinitely merciful deity will forgive and save all, in the end.)

Channing’s formulations also insist that, despite any differences, all men are creatures of God and, as such, deserve to be treated in a fair and equal fashion – marked by a sense of dignity and compassion.

The Unitarian’s message is met by mixed reactions. Traditional Christians regard the view of Jesus as a prophet rather than a divinity as heretical. But others, more drawn to Enlightenment and Deist thought, embrace its emphasis on free will and the idea that good works open a path to salvation for every man.

One early convert to Unitarianism is none other than John Quincy Adams, who joins the church in 1826 after growing up within the stern tenets of Calvinism, and embraces his mission to end slavery in America.

1820-Forward

The Transcendentalists Preach Simplification

Transcendentalism is another movement that springs up at Harvard Divinity School during the 1820’s and 1830’s in conjunction with debates surrounding Unitarianism.

Both philosophies share a conviction that man is inherently good and is capable of attaining salvation through exercising reason and free will on behalf of social progress.

Transcendentalists emphasize two other beliefs.

One is that the natural world serves as a powerful symbol of God’s hand in the universe, and an inspiration to man to return to the simplicity and purity it offers.

If the Unitarians rely mainly on the intellect to guide its followers, the Transcendentalists find inspiration in the beauty, tranquility and lessons found in the great outdoors. For them, nature “transcends” the limited works of man, especially in the often debased realms of politics and organized religion, and also in the trend toward materialism and greed.

The other Transcendentalist theme focuses on the unlimited potential of individual men and women to reshape their lives and their societies.

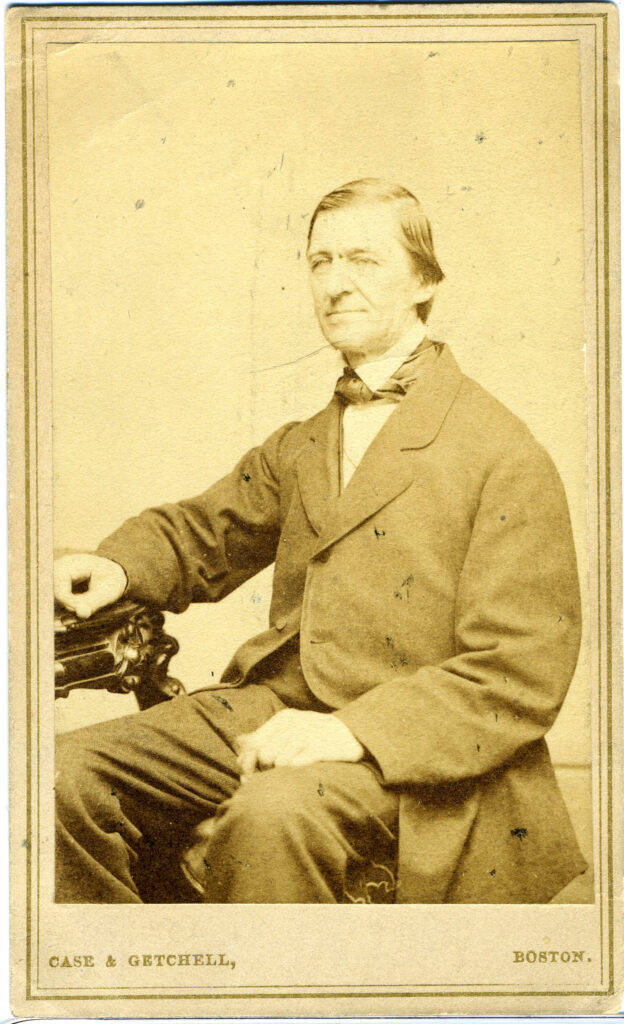

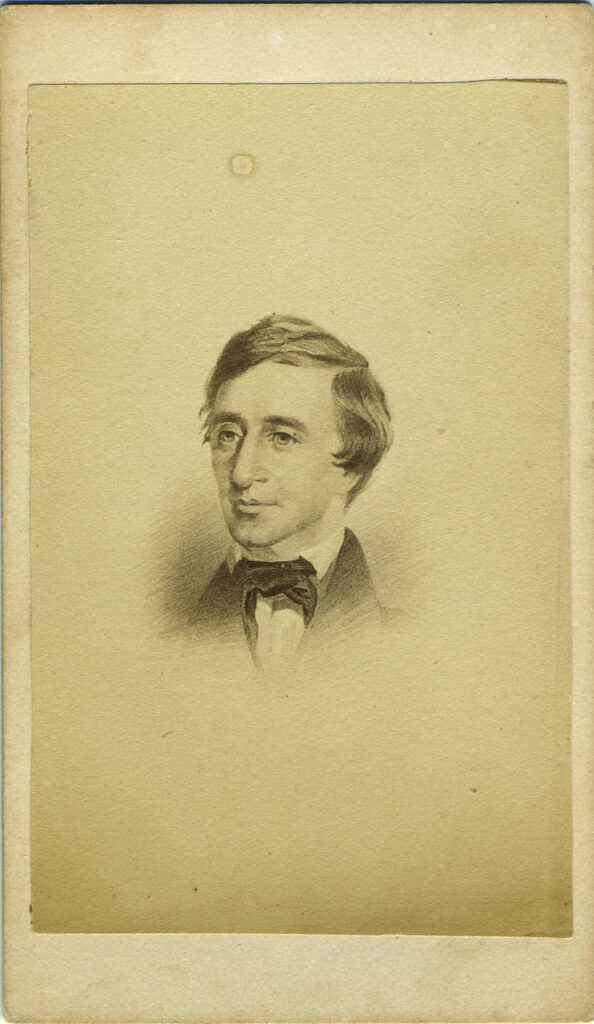

These messages will be developed over time by two leaders of the Transcendentalist movement, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Emerson is the intellectual, at home within the social milieu of Harvard and Cambridge, eager to debate and lobby for his views. Thoreau is the rebel, inclined to lengthy retreats into the woods at Walden Pond to gain perspective on life, and ever ready for personal acts of “passive defiance” against government actions that violate his sense of justice.

Thoreau’s consistent mantra – “simplify, simplify” – argues that salvation lies in a return to the enduring values found in nature: astonishing beauty, balance and tranquility, away from the vexations and distractions inherent in modern society.

Emerson’s messages are two-fold. First he rails against what he sees as America’s growing focus on securing possessions (“things”) in this world rather than eternal salvation in the next.

Things are in the saddle and ride mankind.

Second, he challenges every man to live up to the amazing potential that lies within.

We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds… A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men. So shall we come to look at the world with new eyes. It shall answer the endless inquiry of the intellect, — What is truth? and of the affections, — What is good? by yielding itself passive to the educated… Will. …Build, therefore, your own world. As fast as you conform your life to the pure idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions. A correspondent revolution in things will attend the influx of the spirit.