Section #7 - The Black Experience

The Black Experience

You are there:

Four days after Christmas 1846 Robert H. Wade receives $500 from H.T. Jones in full payment of a family of negroes, big Elba (28 years old), Martha (7 years) and James (2 years)…

Which slaves I warrant to be sound and sensible with the exception of perceivable scars.

The cruel institution of chattel slavery in the Americas gets underway between 1600 and 1800 when some 11 million black people are kidnapped from their homes along the west coast of Africa (from Senegal to Angola) and shipped west across the Atlantic. The Portuguese import 5 million of these Africans for their mining operations and sugar cane fields in Brazil; and the Dutch claim another 4.5 million for sugar cane production in the West Indies.

About 500,000 eventually arrive in North America.

They first appear in August 1619 when the private British ship White Lion drops anchor on the James River near Hampton, Virginia. In exchange for “victuals,” the ship commander, John Jope, hands over “20 and odd” Africans seized earlier in a raid on a Spanish slave ship. They become the property of Sir George Yeardley, the sitting Governor of Virginia, and are held then at Jamestown.

From there it spreads over the next 175+ years to all thirteen colonies as an integral part of America’s economic growth. By 1730, Rhode Island emerges as the focal point for slave trading as part of the burgeoning market for rum. Its thirty distillers produce an option to French brandy preferred by slave dealers along the African coast. To satisfy their thirst a “triangular trade” pattern is born, with the dealers shipping slaves to Cuba and Hispaniola to process sugar cane into molasses which is then sent along to the Rhode Island for processing into the rum transported to Africa.

This system lasts until the turn of the century when the population of potential African captives is totally depleted, and the American Congress passes an 1808 bill banning all further international slave trading.

By that time, however, the role of chattel slavery in America has shifted dramatically.

In the North, the move is already well underway to create a “modern economy,” based on Adam Smith’s brand of capitalism and industrialization. While slavery is officially banned, anti-black racism remains, and the freed black population is segregated and maligned.

Meanwhile in the South, chattel slavery has become essential to economic growth. Those enslaved provide the labor required to produce the region’s four main cash crops: tobacco, rice, sugar and cotton. Then they are treated as a “commodity” unto themselves, being “bred” by owners in the east for sale to new plantation start-ups in the west.

Thus the slave population in America grows from 698,000 in 1790 to 1,538,000 in 1820 and 3,953,000 in 1860. By then almost 54% have been transported away from the coastal South to the west.

Trying to comprehend the life experiences of those enslaved is perhaps best accomplished by listening to their own recollections. Some come to us through interviews conducted with survivors in a 1936-38 federal project on the history of slavery. These may be in the original vernacular/dialect of respondents or modified by the authors. Other sources are individual published recollections such as Harriet Jacob’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years A Slave. Finally there are the sharply worded attacks on the national stain leveled by blacks such as David Walker, Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, Sojourner Truth and others.

Moses Grandy of Camden, NC

My business was to keep ferry, and do other odd work. It was cruel living; we had not near enough of either victuals or clothes; I was half starved for half my time. I have often ground the husks of Indian corn over again in a hand-mill, for the chance of getting something to eat out of it. In severe frosts I was compelled to go into the fields to work, with my naked feet cracked and bleeding from extreme cold: to warm them, I used to rouse an ox or hog, and stand on the place where it had lain. I was at that place three years, and very long years they seemed to me.

Oh yes, I want to go home…where dere’s no whips a crackin…I want to go home.

Swing low, sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home…to carry me home.

Words of a Negro Spritual

My mammy said dat slavery wuz a whole lot wusser ’fore I could ’member. She tol’ me how some of de slaves had dere babies in de fiel’s lak de cows done, an’ she said dat ’fore de babies wuz borned dey tied de mammy down on her face if’en dey had ter whup her ter keep from ruinin’ de baby.

Lucy Brown recalls

O miserable race, born to the same hopes, created with the same feeling, and destined for the same goal, you are reduced by your fellow creatures below the brute. The dog is protected and pampered at the board of his master, while the poor African and his descendant, whether a Saint or a felon, is branded with infamy.

James Forten, a successful businessman born free in Philadelphia

Why does the slave ever love? Why allow the tendrils of the heart to twine around objects which may at any moment be wrenched away by the hand of violence? …I did not reason thus when I was a young girl. Youth will be youth. I loved, and I indulged the hope that the dark clouds around me would turn out a bright lining. I forgot that in the land of my birth the shadows are too dense for light to penetrate. There was in the neighborhood a young colored carpenter; a free born man. We became mutually attached, and he proposed to marry me. I loved him with all the ardor of a young girl’s first love. But when I reflected that I was a slave, and that the laws gave no sanction to the marriage of such, my heart sank within me. My lover wanted to buy me; but I knew that Dr. Flint was too willful and arbitrary a man to consent to that arrangement.

Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents of a Slave Girl

Ownership of slaves

Only 1 in 3 southerners can afford to own slaves and 71% of them have fewer than ten. Mega-plantations with 50 or more slaves are limited to less than 1% of all of the region’s households.

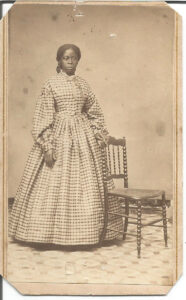

In the Big House or in the Fields

The daily life of those enslaved differs dramatically, depending upon their assigned role. Some serve as field hands, others as house domestics. While both exist without precious freedom or respect, their fates are unequal. House slaves – especially those directly serving the master and mistress — escape from the backbreaking physical labor endured by the field hands.

The women are assigned cleaning, cooking, sewing and gardening chores, along with tending to child care, as so-called “mammy’s.” The men may act as butlers or footmen, tackle household repairs, care for horses and carriages. Both genders are often housed under their owner’s roof and have access to better clothing, diet, and medical care. The “proper” grooming and behavior of house slaves is viewed by guests as a reflection on the master’s wealth and commitment to a gentrified lifestyle.

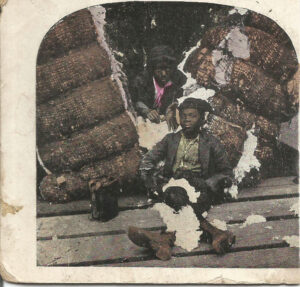

On the other hand, field hands spend their days standing in bug and worm infested dirt and mud or ankle deep water to cultivate rice, tobacco, sugar or cotton. It is punishing labor and intensely monotonous. It is marked by fear at any moment of the lash, delivered by a displeased or arbitrarily sadistic overseer. It is also endless. The only way out is death, and death is all around, in the faces of the young and the old, all accelerated by meager rations, run-down living quarters and flimsy attire.

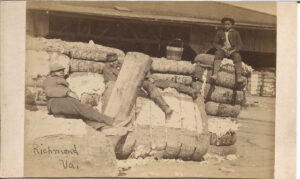

The slave’s “worth” is measured by their daily output. On a cotton plantation, a crop planted around April 1 is ready to be harvested and sent to the ginning mill in July. An average field hand, bent over or crawling in the hot sun, might pick about 100 lbs. of cotton bolls a day, enough to fill up two 12-foot tall “drag-along” sacks. The close of each day is marked by exhaustion.

During the planting and harvest season, we had to work early and late. The men and women were called at three o’clock ’n the morning, and were worked on the plantation till it was dark at night. After that they must prepare their food for supper and for the breakfast of the next day, and attend to other duties of their own dear homes. Parents would often have to work for their children at home, after each day’s protracted toil, till the middle of the night, and then snatch a few hours’ sleep’ to get strength for the heavy burdens of the next day.

Thomas Jones from North Carolina

Mr. Hodge sold me to Mr. Gooch, the cotton planter in Cashaw county. As soon as he got home, he immediately put me on his cotton plantation to work, and put me under overseers, gave me allowance of meat and bread with the other slaves, which was not half enough for me to live upon, and very laborious work. Mr. Gooch did not mind my grief, for he flogged me nearly every day, and very severely.

Moses Roper of Cashaw County, South Carolina

Official charges for applying lashes

On August 2, 1852, Mr. H.G. Hayden is handed an invoice for $2.12 by Maryland state judge P.G. Love for administering “15 stripes” to his slave Jno Tracy. The invoice itemizes the total cost as follows: 174.5 cents to T. Mattingly for delivering 15 stripes; 25 cents administrative costs for swearing & witnesses; and 12 ½ cents to the Judge.

An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, But in Particular To Those of the United States of America penned in 1829 by David Walker, born to a free mother in Delaware.

We colored people are the most degraded, wretched, and abject set of beings that ever lived…We are destined to dig (the white man’s) mines and work their farms, and thus go on enriching them from one generation to another with our blood and our tears!!!!

An observer may see there, a son take his mother, who bore almost the pains of death to give him birth, and by the command of a tyrant, strip her as naked as she came into the world, and apply the cow- hide to her, until she falls a victim to death in the road! Can the Americans escape God Almighty? If they do, can he be to us a God of Justice? I would suffer my life to be taken before I would submit.

Oh! my God, I appeal to every man of feeling – is not this insupportable? Oh pity us, we pray thee, Lord Jesus.

The cause of the black man’s suffering is the white man’s greed and unmerciful quest for power. The whites have always been an unjust, jealous, unmerciful, avaricious and blood-thirsty set of beings, always seeking after power and authority. Ever since we have been among them, they have tried to keep us ignorant, and make us believe that God made us and our children to be slaves to them and theirs.

I tell you Americans! That unless you speedily alter your course, you and your Country are gone!!!!!! For God Almighty will tear up the very face of the earth!!! I call God, I call Angels, I call men to witness, that the destruction of the Americans is at hand, and will be speedily consummated unless they repent.

There are certain secluded and out-of-the-way places, even in the state of Maryland, seldom visited by a single ray of healthy public sentiment—where slavery, wrapt in its own congenial, midnight darkness, can, and does, develop all its malign and shocking characteristics; where it can be indecent without shame, cruel without shuddering, and murderous without apprehension or fear of exposure.

Frederick Douglass captures the sinister aura of plantation life in his autobiography.

My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!

Frederick Douglass captures the sinister aura of plantation life in his autobiography.

I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm…What she produces is an addition to the capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption.

Thomas Jefferson on the “value” of his female slaves

Durin’ slavery if one marster had a big boy en ‘nuther had a big gal, de marsters made dem libe tergedder. Ef’n de woman didn’t hab any chilluns, she wuz put on de block en sold en ‘nuther woman bought. You see dey raised de chilluns ter mek money on jes lak we raise pigs ter sell.

Enslaved William Ward of Georgia on the practice of breeding

I goes to de missy and tells her what Rufus wants and missy say dat am de massa’s wishes. She say, “Yous am de portly gal and Rufus am de portly man. De massa wants you-uns for to bring forth portly chillen. I’s thinkin bout what de missy say, but say to mysef, “I’s not gwine live with dat Rufus.” De nex‟ day de massa call me and tell me, “Woman, I‟s pay big money for you and I‟s done dat for de cause I wants yous to raise me chillens. I’s put yous to live with Rufus for dat purpose. Now, if you doesn‟t want whippin‟ at de stake, yous do what I wants.” I thinks ‟bout massa buyin‟ me offen de [auction] block and savin‟ me from bein‟ sep‟rated from my folks and ‟bout bein‟ whipped at de stake. Dere it am. What am I‟s to do? So I ‟cides to do as de massa wish and so I yields. . . .”

Hilliard Yellerday tells of her futile attempts to avoid childbearing

Two South Carolina owners Davison McDowell and David Gavin react to “breeding losses.”

Sibby miscarried, believe she did so on purpose. Stop her Christmas (gift) and lock her up.

Celia’s child, about four months old, died Saturday the 12th. That is two Negroes and three horses I have lost this year.

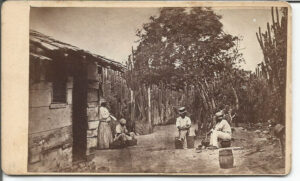

Food, shelter and clothing.

During breaks, “slave food” is carried in pails to the fields. The typical diet is loaded with starch, in the form of cornmeal, and fatback, from salted pork. Access to vegetables and fruit goes to slaves lucky enough to maintain their own small garden plots. Field slaves live in dirt floor log cabins held together by clay-based mortar and vulnerable to rain in the summer and cold in the winter. Their dress is derived from flimsy “Negro cloth,” worn until disintegration. Many go shoeless; others wear “Negro brogans.”

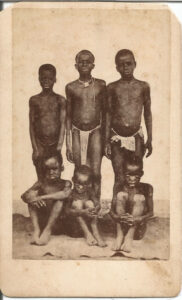

Illness and death rates

The living conditions for those enslaved leaves them vulnerable to a host of killing diseases, including malaria, cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis and pneumonia. Mortality rates for slave babies and children up to age 14 are twice as high as for their white counterparts, and life expectancy for all black people is only 21 years as opposed to 42 years for whites.

State of Ohio’s “Black Codes”

All blacks seeking permanent residence must produce court papers proving they are free rather than run-away slaves; and post a $500 bond backed by two people to guarantee their “good behavior.”

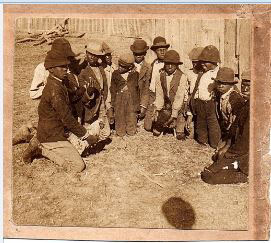

The “Amfield Coffle of 1834” as symbol of domestic slave trading

In August the slave trading firm of Franklin and Armfield gather 300 of their enslaved captives and embark on a 650 mile overland journey from Alexandria, Virginia to Nashville, followed by another 600 barge trip to the auction houses in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans. A witness describes the start of the march:

Armfield sat on his horse in front of the procession, armed with a gun and a whip. Other white men, similarly armed were arrayed behind him. They were guarding 200 men and boys lined up in twos, their wrists hand-cuffed together, a chain running the length of their hands. Behind the men another 100 women and children were tied with rope. Then came six or seven big wagons carrying food, infants, and suits of clothing reserved to display the negroes at auction.

The “coffle” moves at about 20 miles a day arriving in Nashville in mid-September, where Franklin loads the slaves on barges which move along the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers then down the Mississippi to auction house located at Forks of the Road, near the end of the Natchez Trace. It has removed to this remote site after Franklin is caught in 1833 burying slaves who have died of cholera, causing panic and reprisals by city officials.

Sales at the Forks site follow a ritual, with slaves dressed up in finery and first paraded en masse in front of potential bidders. The men dressed in navy blue suits with shiny brass buttons…as they marched singly and by twos and threes in a circle…The women wore calico dresses and white aprons, with pink ribbons in their hair. After this showing, they are grouped by age and size, within gender. Sales are determined by haggling, not by an auctioneer. Thus a prospective buyer will point to a prospect, who will follow them to a more private site for closer inspection. This typically involves undressing and standing naked while examination is made of teeth and backs, the latter in search of prior whip marks, signaling defiance. Slaves may also be asked to speak, sing or dance, and to describe what work and skills they possess. The entire process is one of abject humiliation.

The auctions are seen as social events, with gawkers outnumbering bidders. Advertisements in local papers boast of “Virginia bred” slaves (meaning compliant) and “fancy girls” (sex slaves) who often go for top dollar. A diary records one such sale of a woman named Hermina:

On the block was one of the most beautiful women I ever saw…She was sold for $1250 to one of the most lecherous looking old brutes I ever set eyes on.

I had seven brothers call Frank and Benjamin and Richardson and Anderson and Miles, Emanuel and Gill, and three sisters call Milanda, Evaline and Sallie, but I don’t know if any of ’em are livin’ now. Me and four of her chillen standin’ by when mammy’s sold for $500.00. Cryin’ didn’t stop ’em from sellin’ our mammy ’way from us.

Carter Johnson tells of watching his mother sold off at auction

I wish to inquire after my relatives whom I left in Virginia about twenty-five years ago. My mother’s name was Matilda. My name was Mary. I was nine years old when I was sold to a trader named Walker, who carried us to North Carolina. My younger sister Bettie was sold to a man named Reed, and I was sold and carried to New Orleans and from there to Texas. I had a brother, Sam, and a sister, Annie, who were left with mother. If they are alive, I will be glad to hear from them.

Mary Haynes seeks information about her lost sister.

Run-aways and retribution

According to historian John Hope Franklin, some 50,000 to 60,000 slaves attempt to run-away each year. Eight in ten are men, typically around 20 years old and most try to escape alone. Given the high “market value” of each slave ($377 in 1850), owners rely on various resources to retrieve their “property.” First in line are what the slaves call “patterollers,” a slurring of the word “patrollers.” These are poor white men living rough around the plantations who often use dogs to pursue their prey. David Turner of Hardeman County, Tennessee, boasts of his bloodhounds:

I have two of the finest bloodhounds for catching negroes in the southwest. They can take the trail twelve hours after the negro passed and catch him with ease, and I am ready at all times to go after runaways.

Those who elude the “patterollers” are chased by itinerant bounty hunters, often supported by newspaper ads with crude descriptions of the run-away and rewards typically in the $25 range. Some escape for good, over time with help from the Underground Railroad. Those captured often face harsh retribution, in one case memorialized by former slave W. L. Brost:

The (runaway) was put in the whipping post. They was two holes cut for the arms stretch up in the air and a block to put your feet in, then they whip you with a cowhide whip. I remember how they kill him…He was stubborn and had been lashed before. They strip his clothes off and then the man stand off and cut him with the whip. The cuts about half inch apart. After they whip him they tie him down and put salt on him. Then after he lie in the sun awhile they whip him agin. But when they finish he dead.

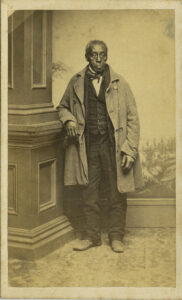

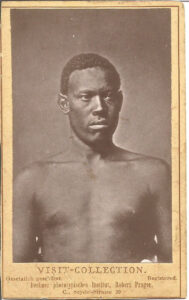

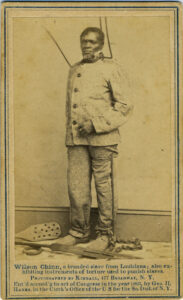

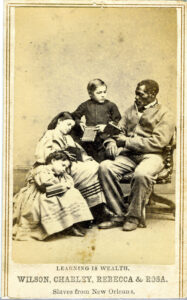

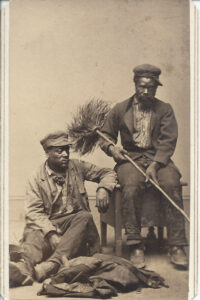

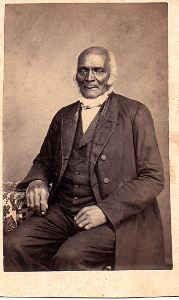

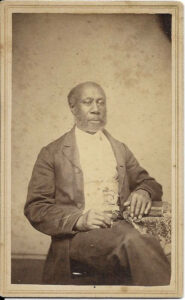

Wilson Chinn is about 60 years old, he was “raised” by Isaac Howard of Woodford County, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters “V. B. M.” Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm.

Slave branding as reported by Harper’s Weekly

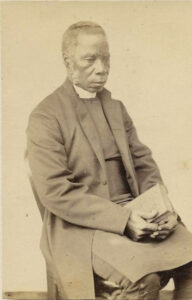

Henry Highland Garnet, run-away, Presbyterian preacher and editor calls for defiance at the 1843 National Negro Convention in Buffalo:

Two hundred and twenty seven years ago, the first of our injured race were brought to the shores of America. …The first dealings they had with men calling themselves Christians, exhibited to them the worst features of corrupt and sordid hearts; and convinced them that no cruelty is too great, no villainy and no robbery too abhorrent for even enlightened men…when influenced by avarice and lust. .

The bleeding captive plead his innocence, and pointed to Christianity who stood weeping at the cross. …But all was in vain. Slavery had stretched its dark wings of death over the land, the Church stood silently by, the priests prophesied falsely, and the people loved to have it so.

The colonists tried to blame slavery on Britain, but then embraced it on their own. The colonists threw the blame upon England. ..But time soon tested their sincerity. In a few years the colonists grew strong, and severed themselves from the British Government…, did they emancipate the slaves? No; they rather added new links to our chains. ….

The time has come to recognize that God views it as sinful to continue submitting to this oppression. …He who brings his fellow down so low, as to make him contented with a condition of slavery, commits the highest crime against God and man. Brethren, your oppressors aim to do this. They endeavor to make you as much like brutes as possible. …

TO SUCH DEGREDATION IT IS SINFUL IN THE EXTREME FOR YOU TO MAKE VOLUNTARY SUBMISSION….. Your condition does not absolve you from your moral obligation. The diabolical injustice by which your liberties are cloven down, NEITHER GOD, NOR ANGELS, OR JUST MEN, COMMAND YOU TO SUFFER FOR A SINGLE MOMENT. THEREFORE IT IS YOUR SOLEMN AND IMPERATIVE DUTY TO USE EVERY MEANS, BOTH MORAL, INTELLECTUAL, AND PHYSICAL THAT PROMISES SUCCESS. Brethren, it is as wrong for your lordly oppressors to keep you in slavery.

Brethren, the time has come when you must act for yourselves. It is an old and true saying that, “if hereditary bondmen would be free, they must themselves strike the blow.” You can plead your own cause, and do the work of emancipation better than any others. It is better to “die freemen than live to be slaves.”

Uprisings

The entire plantation system in the South hinges on the strict obedience of slaves to the will of their masters – with various forms of terror used to enforce compliance. Thus those enslaved quickly learn to fear their owners. But fear goes both ways, for underneath the gloss of apparent submission lies anxiety about retribution. Thomas Jefferson’s words reflect this anxiety:

I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that His justice cannot sleep forever.

No one knows for sure how many acts of rebellion occur in America over the centuries, but several are recorded in history. The most famous seem prompted by the black uprising in Hispaniola in 1791 led by Toussaint Louverture. This ends with France removed from power, emancipation, and the new nation of Haiti governed by black leaders. None of the American uprising are this successful.

In 1800, an enslaved blacksmith named Gabriel and his brother Martin, a preacher, plan to gather their forces, march on Richmond under the Patrick Henry banner (“Liberty or Death”), kill as many whites as possible, and then sail off to Haiti to survive. But word of their plot slips out in advance, and the militia quickly tracks them down and hang a total of 26 men, including Gabriel and Martin.

Five years later, word spreads of an incident at Chatham Manor owned by George Washington’s friend, William Fitzhugh, with slaves whipping their overseer and four other whites, before being subdued.

A much broader rebellion takes place in 1811 along Louisiana’s “German Coast” led by a mulatto slave named Charles Deslondes who also hopes to repeat the revolution in Haiti. Deslondes plans well and recruits an initial band of 25 slaves to join his attack. They hack one victim to death on a local plantation before heading 20 miles south to New Orleans. But before they arrive, they are met by the militia and forced to surrender after running out of ammunition during a pitched battle. Roughly twenty blacks are killed in action and fifty are captured, including Deslondes who is tortured and killed. Other captives are hanged or shot and their severed heads are displayed on poles along the road leading to New Orleans.

In 1822 the banner is picked up by a slave named Denmark Vesey, who spends his youth in Haiti, witnesses the Toussaint revolt, and is brought to Charleston as a house slave. Once there he buys his freedom and becomes an influential pastor in the Mother Bethel AME Church. When his pleas to end slavery fall on deaf ears, he decides to act on his own. He puts together an elaborate plot to form a black army and attack local plantations, symbolically on Bastille Day. But again authorities learn of the plan in advance and Vesey, along with 67 suspected coconspirators are summarily hanged and decapitated.

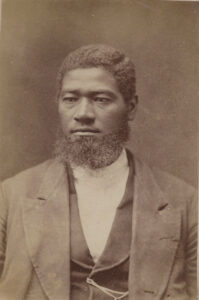

The most publicized and bloodiest uprising follows in 1831 in and around Jerusalem, Virginia. It is led by 30 year old Nat Turner, who has been taught to read the Bible and becomes an informal preacher on his plantation. But his hatred mounts after he and his wife are sold off to different masters, and he vows revenge. It is marked by savagery, beginning with Turner and six accomplices wielding axes to slaughter his master’s family of four asleep in their beds. He is joined by forty other slaves and together they raid 15 homesteads and murder about 60 whites before their momentum is broken by the militia. Turner escapes but is captured two months later. At his trial he remains defiant:

I am not guilty, because I do not feel so…I’m not sorry for killing all those white people. I alone conceived the idea of insurrection, which has been evolving in my mind for several years. And, no I didn’t fail. Our names are now written in blood across the map of this county, nor will we be the last.

Punishment follows swiftly, with proven conspirators hanged and owners lynching any thought to be “troublesome” slaves at will. Nat Turner himself is flayed, beheaded, quartered and ultimately skinned to make “memento purses,” which show up years later in estate sales.

In hindsight, none of these uprisings, from Gabriel to Turner, represent an existential threat to the Southerner’s control over the slave population. Nevertheless each one, in its own way, strikes terror in the minds of white men toward all blacks, in both the South and the North.

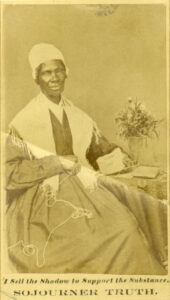

The non-violent protest of Sojourner Truth

Other black leaders search for freedom, equality, common decency and respect through appealing to and chastening the white population in publications and lectures. Among the most compelling are Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass.

Truth’s original name is Isabella Baumfree, born into slavery on a Dutch farm in upstate New York. She marries and has five children before escaping. In 1843 she has a spiritual epiphany, becoming a Methodist and hearing the voice of God telling her to go forth and speak the truth about slavery. From then on she is Sojourner Truth, a Garrison lecturer, known for moving audiences to tears with her plain-spoken cries for equality. Here she asserts her call in the famous refrain “Ain’t I A Woman.”

“Ain’t I a woman?” But what’s all this here talking ’bout? Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to have de best place eberywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place — “and ain’t I a woman?

Look at me. Look at my arm, I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me–and ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it) and bear de lash as well–and ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard–and ain’t I a woman?

Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head. What dis dey call it, Intellect? Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do with woman’s rights or [negroes’] rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little halfmeasure full?

Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner ha’n’t got nothing more to say

Alabama Literacy Law Of 1833

Any person who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read or write, shall upon conviction thereof by indictment, be fined in a sum of not less than two hundred fifty dollars, nor more than five hundred dollars.

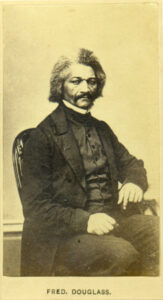

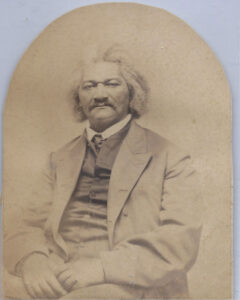

Frederick Douglass becomes the symbol of total racial equality

Douglass does more than any other 19th century figure to show by his words and deeds that black people are equal to whites and that, given a fair start in life, they can be assimilated into American society and given the rights of full citizenship.

The wife of Douglass’ owner treats him kindly and teaches him to read and write before ordered to stop by her husband. He sends the youth to be “broken” by a harsh overseer who succeeds until one day when he finally confronts and back downs his oppressor. In that moment he says “the slave became a man.” Douglass escapes to New York City and then Massachusetts, where he becomes a licensed preacher and joins various abolitionist groups. At age twenty-three he delivers a spontaneous address in Nantucket that leads abolitionist Lloyd Garrison to hire him as a traveling lecturer, and then to publish his autobiography. From there he makes his own way to national prominence, including meetings with Abraham Lincoln which seem to change the President’s mind about the potential for black people to assimilate into American society. On July 5, 1852 Douglass delivers his most famous speech to a mixed crowd of 500 people in Rochester, N.Y. Excerpts follow.

The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro.

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? …Do you mean to mock me, by asking me to speak? I (ask) with a sad sense of the disparity between us (for) I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary!… This Fourth July is yours, not mine….Above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.

Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade, the American slave-trade, sustained by American politics and American religion.

Here you will see men and women reared like swine for the market. Mark the sad procession, as it moves wearily along, and the inhuman wretch who drives them. Hear his savage yells and his blood-curdling oaths, as he hurries on his affrighted captives!

There, see the old man with locks thinned and gray. Cast one glance, if you please, upon that young mother, whose shoulders are bare to the scorching sun, her briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms. See, too, that girl of thirteen, weeping, yes! weeping, as she thinks of the mother from whom she has been torn!

The drove moves tardily. Heat and sorrow have nearly consumed their strength; suddenly you hear a quick snap, like the discharge of a rifle; your ears are saluted with a scream, that seems to have torn its way to the centre of your soul The crack you heard was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on.

Follow this drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slavebuyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude.

Tell me, citizens, where, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.

By an act of the American Congress (Fugitive Slave Act), not yet two years old, slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form.

I take this law to be one of the grossest infringements of Christian Liberty, and, if the churches and ministers of our country were nor stupidly blind, or most wickedly indifferent, they, too, would so regard it… At the very moment that they are thanking God for the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, and for the right to worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences, they are utterly silent in respect to a law which robs religion of its chief significance and makes it utterly worthless to a world lying in wickedness.

Oh! be warned! be warned! a horrible reptile is coiled up in your nation’s bosom; the venomous creature is nursing at the tender breast of your youthful republic; for the love of God, tear away, and fling from you the hideous monster, and let the weight of twenty millions crush and destroy it forever!… The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity as a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad: it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing and a bye-word to a mocking earth.

I have detained my audience entirely too long already… Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.

There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind… Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe… The fiat of the Almighty, “Let there be Light,” has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light…

In the fervent aspirations of William Lloyd Garrison, I say, and let every heart join in saying it: God speed the year of jubilee, The wide world o’er! When from their galling chains set free, Th’ oppress’d shall vilely bend the knee, And wear the yoke of tyranny, Like brutes no more. That year will come, and freedom’s reign.To man his plundered rights again Restore.

God speed the day when human blood Shall cease to flow!

In every clime be understood, The claims of human brotherhood,

And each return for evil, good, Not blow for blow;

That day will come all feuds to end,

And change into a faithful friend Each foe.

No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein; and the legislative assembly shall provide by penal laws for the removal by public officers of all such negroes and mulattoes, and for their effectual exclusion from the state, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the state, or employ or harbor them.

1857 Oregon State Constitution – Article 1. Section 35

No Negro, Chinaman, or Mulatto shall have the right of suffrage.-

Article 2. Section No.6

Note: popular votes to exclude all blacks from living within state borders are passed in many other Northern states, including Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Kansas and California. But Oregon is the only state to officially ban black residence in its constitution. Oregon voters finally called for removal of the constitutional ban in 1926, after refusing to do so in a 1900 vote.

The “Market Value” Placed On Human Beings

While the cotton produced by the South in 1860 is worth some $1.2 Billion, the “market value” at auction of their nearly 4 million slaves is estimated at just over $3 Billion. This at a time when the total U.S. GDP is $4.4 Billion.

“Market Value” Of Those Enslaved

| Year | # Slaves | $/ Slave | Total $ |

| 1840 | 2,487M | $377 | $ 938MM |

| 1845 | 2,823 | 342 | 965 |

| 1850 | 3,204 | 377 | 1,208 |

| 1855 | 3,559 | 600 | 2,135 |

| 1860 | 3,954 | 778 | 3,076 |