Section #11 - Our Money Supply, Banking Systems and Financial Crises

Our money supply, banking systems and financial crises

You are there:

The new nation creates its own money supply and banking systems on its way to economic successes along with a few periodic set-backs.

Accompanying the colonial settlers comes the age old British monetary system known as the “Pound Sterling,” manifested in hammered or minted coins made from various metals and in varying weights. The anchor for “value” is the one L coin comprising 12 ounces of pure silver. While some coins are also minted in gold, the vast majority of daily transactions involve shillings (also called “bobs”) or pence, on down to farthings.

The British Pound Sterling Money In Colonial America

| Denomination | # Shillings | # Pennies |

| Pound/Sovereign/Guinea | 20 | 120 |

| One “Quid” | 100 | |

| Half Sovereign | 10 | 60 |

| Crown | 5 | 30 |

| One shilling (“Bob”) | 12 | |

| Tanner | 6 | |

| Tuppence | 2 | |

| One pence | 1 | |

| Farthing | 1/4th |

To retain control over its American colonies, the Crown disallows all local minting, something which becomes academic when the hoped-for deposits of gold and silver fail to materialize.

But the effect is that America soon runs out of money to complete needed transactions.

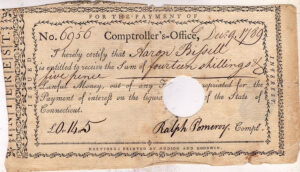

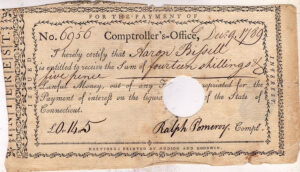

This initially leads to bartering, whereby plugs of tobacco, fur pelts or “wampum” (tribal beads) are exchanged for desired goods. But this is too arbitrary a system, and one by one the Colonies follow Massachusetts’ 1690 lead in printing paper Bills of Credit (“IOU”s) as stand-ins for minted money.

The British put up with these local banknotes until it becomes clear that the face value of the Bill is no longer “backed” by a sufficient supply of minted coins to be credible. In effect, the Bills become worth less and less, and Britain’s merchants demand action by Parliament. This leads to the Currency Acts of 1751 and 1764 which curtail the printing of these Bills and their use in paying off trading debts.

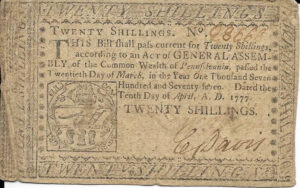

Once the Revolutionary War gets under way, the Continental Congress authorizes its own currency known as “dollars,” the anglicized version of the German “thaler,” the first coin minted from silver in 1519. Thus the British “Pound Sterling” gives way to “Continental Dollars.”

It’s unclear how many of these minted dollars actually go into circulation, but they are made from brass and pewter in addition to silver. Instead of coins, almost all Continental Dollars appear as banknotes, printed and issued by individual sovereign states. Denominations include 1/6th, 1/3rd, one-half, and 2/3rds of a dollar as well as higher values up to $80. (“Pennies or Cents” do not appear until the 1792 Coinage Act.)

The fate of the Continental Dollars mirrors that of the British controlled banknotes – namely, a loss of trust in the face value of the notes owing to a lack of “backing” in actual silver or gold. The nation limps along with the flaws throughout the Articles of Confederation period from 1781-1789. But by the time the delegates gather in Philadelphia in 1787 to write a new constitution, the epithet “not worth a Continental” has been firmly established in the public lexicon.

The task of fixing this problem rests with Alexander Hamilton, a financial wizard who is President George Washington’s right-hand man and the first Secretary of the Treasury.

One of his early actions is the 1792 Coinage Act which sets up a U.S. minting operation and defines the coins that will be made available. The anchor here is the United States Dollar comprised of fine silver and weighing approximately the same as Spanish Dollars known as “pieces of eight.” The copper pennies are important at the time since an unskilled laborer would be making 20 cents a day on average.

Minted U.S. Coins As Of 1792

| Denomination | Value | Metal |

| Eagles | $10.00 | gold |

| Half Eagles | 5.00 | gold |

| Quarter Eagles | 2.50 | gold |

| Dollars | 1.00 | silver |

| Half-dollars | .50 | silver |

| Quarter dollars | .25 | silver |

| Dismes (dimes) | .10 | silver |

| Half-dismes (nickels) | .05 | silver |

| Cents or pennies | .01 | Copper |

| Half cents | .005 | copper |

From there the 32 year old Hamilton sets his sights on building a diversified industrialized economy based on the capitalism preached by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith.

To do so, he wants a monetary system that insures stability in the value of the dollar, while also recognizing the need to greatly expand the amount of money in circulation to jumpstart innovation and growth. Progress will follow if he can get sufficient capital (money) into the hands of clever men who are intent on starting up their own businesses – to mill grain or make rum, to transport goods over roads or waterways, to open store-fronts in small towns or big cities.

To achieve his goal Hamilton must address two problems: the supply of minted gold and silver coins in America is insufficient; and the option, the Continental banknotes; are no longer worth the paper they are printed on.

Lacking a domestic supply of precious metal for minting, his only way out lies in restoring confidence among a skeptical public toward banknotes. As he says:

There is scarcely any point in the economy of national affairs of greater moment than the

uniform preservation of the intrinsic value of the money unit. On this, the security and

steady value of property essentially depend.

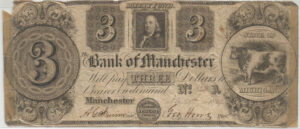

To restore trust, Hamilton will try to insure that those entities handling “Bills of Credit” – largely unchartered state banks – maintain a sufficient supply of gold or silver coins on hand to “back up” their face values. He decides that a ratio of 3:1 (soft money to hard money) will work. For every $3.00 worth of banknotes in circulation the bank must maintain $1.00 worth of coins.

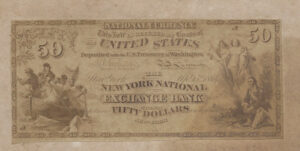

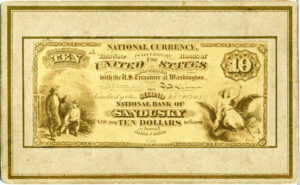

To enforce this ratio, he promises to bring “fraud charges” against any firm refusing a customer’s “demand” to exchange banknotes for gold or silver coins on a dollar for dollar basis. This “exchange pledge” will not, however, becomes explicit until around 1861, as in this promise:

Ten Dollars In Gold Coin Payable To Bearer Upon Demand

Hamilton then adds to his “enforcement power” by another very controversial move – creation of the First Bank of the United States in February 1791.

It is a “private corporation” owned not by the government, but by individual stockholders expecting to make a profit on their investments. The charter calls for it to begin with $10 million in capital, allocated across 250,000 shares of stock, offered at $400 apiece. The federal government owns $2million of this stock, with the remaining $8 million owned by outside stockholders, each required to make 25% of their buy-in payments in gold or silver specie.

Hamilton sees his “BUS” as having two main public sector functions:

- ∙ First, to handle the government’s monetary needs – taking in federal revenue and paying bills to cover federal spending — while operating at arm’s length to avoid conflicts of interest.

- Second, to help “regulate” the banking system and money supply across the states.

“Bank regulation” under Hamilton will take several forms. Formal “chartering” of state banks will accelerate – from a total of three in 1790 to over 300 three decades hence. The U.S. Mint will take control over setting and insuring weight standards and values for gold and silver coinage. The BUS will also flex its muscles with state banks who appeal to it for cash loans. Those local banks in compliance with the 3:1 soft to hard money target, will get loans at lower interest rates; those out of compliance, will suffer higher interest charges or be turned down entirely.

But Hamilton’s money plan is met by fierce oppositon from Anti-Federalists like Thomas Jefferson who regard “soft money” as a proven failure; believe it will lead to wild banker speculation and lost value; and fear a disaster if all holders simultaneously demanded their gold and silver.

They also regard the U.S. Bank as an infringement on the sovereign authority of the states, and suspect that the private investors will manipulate investments to line their own pockets. To address these issue, they add several constraints: the BUS charter will expire in 20 years; it must be run independently from the government and cannot buy US bonds; directors will be rotated every five years; no foreigners will be allowed to own stocks; and the books can be audited at any time.

Jefferson’s distrust of the BUS – and of Hamilton – is unwavering. He writes:

Hamilton’s financial system… has two objects; 1st, as a puzzle, to exclude popular under-

standing and inquiry; 2nd, as a machine for the corruption of the legislature; for he avowed

the opinion, that man could be governed by one of two motives only, force or interest;

force, he observed, in this country was out of the question, and the interests, therefore, of

the members must be laid hold of, to keep the legislative in unison with the executive.

Despite Jefferson’s skepticism, what follows is an unequivocal long-term success for Hamilton’s overall economic strategy, as evident in the nation’s GDP growth between 1790 and 1860. Of all the global powers, only the United Kingdom still enjoys more total wealth than the United States.

Gross Domestic Product For The United States*

| Year | 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

| GDP (MM) | $189 | $480 | $706 | $710 | $1,022 | $1,574 | $2,581 | $4,387 |

| Per Capita | 48 | 91 | 98 | 74 | 79 | 92 | 111 | 139 |

Still there are ups and downs along the way, including what appears to be a steady depreciation in the true value of the dollar. This conclusion is based on very limited data, the main source being a long-term study of prices paid by Vermont families for various goods. It shows that money valued at $51 in 1800 depreciated by roughly 50% to $27 by 1860.

Depreciation In Purchasing Power Of Dollar Among Vermont Farm Households

| Year | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

| Value | $51 | $47 | $42 | $32 | $30 | $25 | $27 |

| Index | 100 | 92 | 82 | 62 | 57 | 48 | 52 |

Over this timeframe the number of chartered banks and outstanding loans grow quite steadily.

Number of Chartered Banks and Loans Outstanding

| Year | 1820 | 1825 | 1830 | 1835 | 1840 | 1845 | 1850 | 1855 | 1860 |

| # Banks | 327 | 330 | 381 | 704 | 901 | 707 | 824 | 1,307 | 1,562 |

| Loans ($MM) | $55.1 | $88.7 | $115.3 | $365.1 | $462.9 | $288.6 | $364.2 | $576.1 | $691.9 |

Where disruptions in the growth of the U.S. economy and erosions in the value of the dollar occur, they trace primarily to periods of intense speculation by bankers followed by disappointing outcomes.

The basics of banking are fairly simple. Money flows into banks in the form of “deposits” with promises of returning the principal plus an agreed to amount of interest. Bankers take these deposits and invest them as “loans” in what they hope will be profitable projects. For the banks to remain viable the profits from their loans must exceed the interest on their deposits. That works as long as bankers make the right calls on their loan projects.

But at times bankers make the wrong bets, especially when they think they spot investments offering “windfall profits.” The result becomes widespread economic pain.

A brief history of America’s financial collapses

The first such error comes with the War of 1812.

A continental army needs to be formed and equipped, housed and fed, transported and re-supplied, all in a short time-frame and with no clear-cut end in sight. Additionally, the British blockade of American ports greatly increases the need for domestically produced goods.

The Economy Booms During War Of 1812

| GDP | 1812 | 1813 | 1814 |

| $ (MM) | $786 | $969 | $1,078 |

| % Change | 2% | 23% | 11% |

| Per Cap | $103 | 123 | 133 |

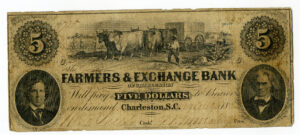

Taken together, this increased “demand” represents a windfall opportunity for a host of suppliers – who turn to local bankers to borrow the money needed to invest in added capacity. The banks are only too happy to comply with this increased demand for more loans, often at higher than usual rates of interest.

But many banks face a problem: a lack of sufficient cash on hand to complete the loans. They solve this problem by resorting to a time-honored tactic – simply printing and issuing more soft money banknotes, while ignoring the rules about properly “backing them” with reserves of gold or silver.

These violations are difficult to spot and control after the Anti-Federalists refuse to renew the U.S. Bank charter in 1811, thus ending its regulatory enforcement over the reserves.

Along with the artificial expansion of the money supply comes inflation — a jump in the prices of goods reflecting a decline in the “true value/buying power” of each dollar.

Still by 1813 the American economy is enjoying a flat-out “boom cycle.” Those who have taken out loans for investment are reaping large gains in profit, and are able to pay off their debts to the banks in full and on time. In turn, bankers are able to meet their interest payments to depositors, while also increasing their own private profits.

Prosperity continues until the war with Britain comes to a close in 1815. At which time, the ramped-up “demand” for goods suddenly drops, and suppliers find themselves with excess inventory they can’t sell, along with excess operating costs they need to shed.

This signals the shift from “boom cycle to bust cycle.” The rapid economic growth evident in 1813 and 1814 is replaced by sharp declines beginning in 1815.

“Bust Cycle” Begins At End Of War

| 1814 | 1815 | 1816 | |

| $ (MM) | $1,078 | $ 925 | $ 819 |

| % Change | 11% | (14%) | (11%) |

| Per Capita | $133 | $111 | $ 96 |

As alarm sets in, Treasury Secretary Gallatin finally persuades Madison in 1816 to charter the Second U.S. Bank to regain control over the money supply.

But nothing is able to forestall the “Financial Panic of 1819,” considered by economists as America’s first great depression.

Once borrowers cannot pay back their loans, the banks are left without enough cash to pay off their depositors – and the system collapses.

In a desperate search for more cash, banks “foreclose” on borrowers whose loans are in default. Instead of added dollars, however, these foreclosures only deliver assets (e.g. homes, farms, goods) the banks don’t want to hold and can only sell at rock bottom prices.

Public anger mounts and Congress is called upon to pass “stay laws” delaying loan repayments and foreclosures. The hostility is captured by Ohio congressman William Henry Harrison:

I hate all banks!

As this “squeeze” continues, the Second Bank of the United States makes things more difficult by requiring that state banks complete future transactions with the BUS using gold or silver “specie” rather than paper currency.

On the surface, this move is sound. The federal government still needs to pay off its own sizable debts from the 1812 War to foreign nations who demand minted coins rather than paper banknotes. In addition, the BUS requirement for “hard specie” is intended to ensure adequate bank reserves, reduce over-printing of soft currency, and reduce inflation. All worthy goals.

But many local banks who need to borrow cash from the BUS to pay off depositors are unable to do so because their inventory of specie is too low.

All that’s left for these banks is to refuse payments on demand – and when this happens, panic sets in among their customers. “Runs on banks” follow as people line up to withdraw their life’s savings before whatever cash left on hand runs out.

This simply accelerates the downward cycle until the target banks are forced to close their doors.

In 1818 the State Bank of Kentucky is first to suspend all operations – a fate shared by roughly 30% of the nation’s state banks over the course of the panic.

As 1819 plays out, all that can go wrong with America’s capitalistic system has gone wrong and

many lives are damaged by its effects.

In Pennsylvania, land values plummet by 75% between 1815 and 1819. Over 50,000 men are unemployed in Philadelphia, and some 1800 are sent to debtor’s prison. Beggars appear on city streets, along with soup kitchens and homeless shelters.

Senator John Calhoun sums up conditions in 1820:

There has been within these two years an immense revolution of fortunes in every part of the Union; enormous numbers of persons utterly ruined; multitudes in deep distress.

In the end, the depression extends over six years, roughly from 1815 to 1820, before a gradual recovery gets under way.

GDP Trends During The Depression Following The War Of 1812

| 1814 | 1815 | 1816 | 1817 | 1818 | 1819 | 1820 | 1821 | |

| $ 000 | 1,078 | 925 | 819 | 769 | 737 | 726 | 710 | 735 |

| % Ch | 11% | (14%) | (11%) | (6%) | (4%) | (2%) | (2%) | 3% |

| Per Cap | $133 | 111 | 96 | 87 | 81 | 78 | 74 | 74 |

Unfortunately, history will show this pattern of economic boom and bust repeating itself in America every two decades or so – thus the panics of 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, 1907, 1929, and so forth.

America’s next recession follows the election in 1829 of Andrew Jackson, who mistrusts both the monetary and banking systems he inherits.

Jackson is convinced that bankers use the “monopoly status granted by the public” to enrich themselves and perhaps even “foreign interests.” Also that this great wealth in the hands of a very few will translate into the power to corrupt the democratic process by “buying” congressmen and votes. And, given the Second Bank’s roots in the East, he is forever certain that it operates on behalf of New England over the southern and western states.

He is particularly opposed to the Second U.S. Bank which Madison re-charters in 1816 during the prior depression. He repeatedly refers to it as “The Monster” and promises to “kill it before it kills me.” In 1833 he succeeds, withdrawing all federal funds and again leaving the central government without regulatory control over the state banks.

From there Jackson sets his sights on slaying his two other financial demons – the first being federal debt which he pays down by 1835, the one and only U.S. President in history to accomplish this.

History Of Federal Debt

| Year | $ (000) | President |

| 1825 | $83,788 | JQ Adams |

| 1829 | 58,421 | Jackson |

| 1830 | 48,565 | Jackson |

| 1831 | 39,123 | Jackson |

| 1832 | 24,322 | Jackson |

| 1833 | 7,002 | Jackson |

| 1834 | 4,760 | Jackson |

| 1835 | 34 | Jackson |

| 1836 | 38 | Jackson |

| 1837 | 337 | Van Buren |

But his other nemesis – periodic erosion in the “true value” of paper banknotes – proves much more intransigent. Jackson is properly convinced that the root cause of the problem rests with bankers who make speculative loans without sufficient reserves in silver and gold.

He is particularly alarmed by the dramatic run-up in 1835 he sees in land sales.

Accelerated Speculation In U.S. Land

| Year | $ Sales (000) | % Change |

| 1831 | $ 3,200 | |

| 1832 | 2,600 | (19%) |

| 1833 | 3,900 | 50 |

| 1834 | 4,800 | 23 |

| 1835 | 14,750 | 307 |

What will happen, he wonders, when the bidding frenzy subsides and speculators find that the true value of the land they bought is much less than they thought? And if, as he suspects, many of the big speculators are the bank owners themselves, will their debt bring down the financial integrity of the entire country? He issues this warning to them:

Gentlemen, I have had men watching you for a long time and I am convinced that you have used the funds of the bank to speculate in the breadstuffs of the country. When you won, you divided the profits amongst you, and when you lost, you charged it to the bank. You are a den of vipers and thieves.

He is equally certain that his duty as president lies in acting before it is too late. He will not leave behind a shaky financial outlook as a legacy, when his term is up.

To correct the problem, he must find a way to curtail the rogue printing of the banknotes which fuel speculation, depreciate the real value of the dollar, and result in debt.

He attempts this by issuing an Executive Order (known as the “Specie Circular”) on July 11, 1836 requiring that future purchases of U.S. land by anyone other than actual settlers be paid off in gold or silver, not in banknotes. (The same move tried by Madison in the 1819 crisis.)

Jackson’s order again rocks the foundation of the financial system in place since Alexander Hamilton’s time. It is widely taken as a signal that the federal government itself is uncertain about the intrinsic value of the banknotes already in circulation. Why else would the President suddenly be asking land investors to pay off their purchases in hard currency rather than soft banknotes?

As this doubt sinks in, the entire economy begins to witness a flight from dollars back into gold and silver – and a contraction of the nation’s money supply. The result being a sudden reversal of Hamilton’s entire system of “credit” to support capitalism.

A nation accustomed to borrowing money today — to buy property, to run a farm, to invest in a business – and paying it back with interest later on, finds that the banks will no longer make these loans. Worse yet, some banks are even demanding that outstanding loans be repaid immediately to protect the survival of their internal owners.

As in 1815, what follows in 1837 is fear, then bankruptcies and foreclosures.

The old General’s last campaign has found and attacked the vulnerabilities of the “fractional” banking system, and slowed the tide of both public and federal debt. But not without a cost. The result will be the second extended recession in U.S. history, which continues for almost seven years and has a devastating effect on Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren.

GDP Trends Before And After The 1837 “Species Circular” Act

| 1835 | 1836 | 1837 | 1838 | 1839 | 1840 | 1841 | 1842 | 1843 | |

| Total GDP ($000) | 1340 | 1479 | 1554 | 1598 | 1661 | 1574 | 1652 | 1618 | 1568 |

| % Change | 10% | 10% | 5% | 3% | 4% | (5%) | 5% | (2%) | (3%) |

| Per Capita GDP | 90 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 92 | 94 | 89 | 84 |

Two more economic set-backs occur prior to the Civil War.

The first arises after the 1846-7 Mexican War and mirrors the boom-bust cycle around the War of 1812, albeit much less severe in depth and duration. Thus the overheated economic build-up in preparing and executing the war is followed by a sharp down-turn following the victory. But it is largely over by 1850.

GDP Trends Around The Mexican War

| 1845 | 1846 | 1847 | 1848 | 1849 | |

| Total (000) | $1859 | 2065 | 2410 | 2427 | 2419 |

| % Change | 9% | 11% | 17% | 1% | NC |

Finally there is the “Panic of 1857,” again driven largely by land speculation in this case linked to the pending development of a transcontinental railroad across the western land ceded by Mexico after losing the war. This involves a guessing game as to which acreage might experience a boom in prices were it to become a train stop in the future. The banks are only too happy to make loans to the land speculators.

An article published in the New York Herald cites the risks associated with this form of gambling:

What can be the end of all this but another general collapse like that of 1837, only upon a much grander scale? The same premonitory symptoms that prevailed in 1835-36 prevail in 1857 in a tenfold degree. Paper bubbles of all descriptions, a general scramble for western lands. . . . The worst of all these evils is the moral pestilence of luxurious exemption from honest labor which is infecting all classes of society.

While the “collapse” never materializes, investor losses associated with the land speculation do slow the rate of GDP growth between 1856 and 1858. After which prospects for a North-South conflict begin to loom large over all future prospects.

GDP Slowdown Related To Western Land Speculation

| GDP | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 | 1857 | 1858 |

| Total ($000) | 3713 | 3975 | 4047 | 4180 | 4093 |

| % Change | 12% | 7% | 2% | 3% | (2%) |

Looking backwards over the threescore and ten years of the republic from 1790 to 1860, one sees monetary and banking outcomes that, despite occasional failures, propels the United States into true prominence on the world stage. Hamilton’s plan is not perfect, but it is superior to Jefferson’s.