Section #4 - The Battles for Tribal Land

The Battles for Tribal Lands: 1826-42

The Native Americans Arrive

Roughly 24,000 years ago, America’s first settlers wend their way across a 1000 mile “land bridge,” formed by a sea level drop in the Bering Straits, which once linked the eastern edges of Siberia to western-most Alaska.

Their facial features signal an Asian heritage, and they are typically dark complexioned. They operate in tribes and become adept at both hunting and gathering. They are the first farmers of the land, sustained by a wide range of indigenous crops, including corn, potatoes, peanuts, chocolate, cotton and tobacco.

Thus the New World is born.

Over time the settlers fan out across the northern continent, east to the Atlantic coast and south through Mexico to the southern hemisphere. By 1500 AD Native American civilizations, comprising perhaps several million people and speaking upwards of 250 unique languages, dot the landscape from coast to coast. Tribal confederations form in places, their signal being a common tongue. In the east, these include the Iroquois, Algonquins and Powhatans:

| Language | Location | Tribes |

| Iroquoian | NY, Canada | Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas |

| Algonquian | E. Canada | Potawatomie, Chippewa, Odawa, Cree, Nipissing, Delaware |

| Powhatan | Virginia | Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Rappahannock, Mattaponi |

The Iroquois are among the more sophisticated tribal societies, with a formal legislative structure in place to reach decisions affecting their union. Voting is done by two separate sets of “sachems” or representatives, one representing the Seneca and Mohawk tribes, the other the Oneida and Cayuga. Breaking ties and issuing vetoes rests with the Onondaga. Ironically this structure is similar to the British Parliament and the American Congress.

After centuries alone, the 1600’s bring the Europeans led by the Spanish conquistadors, with Ponce de Leon in Florida, Hernan Cortez ousting the Aztecs in Mexico, and Francisco Pizarro subduing the Incas along the Pacific coast of South America. Followed by the French ranging from Canada to the Mississippi Valley and the British with their 13 colonies along the Atlantic coast. Each begins in search of gold, silver and other valued commodities.

But the Europeans also seek ownership of land, which to the native tribes is inconceivable given their belief that the earth and sky belong equally to all men. And herein lies the basis for turning largely peaceful relations and commerce between the two cultures into lasting conflict, violence and oppression over time.

Tribal involvement in America’s three early wars for survival also have a lasting negative effect on relationships between the natives and the eventual U.S. government. For two reasons: first, because some tribes end up fighting for the French or British and against the Americans; and second, because some battles pit one tribe against another, thus limiting future coalitions capable of negotiating fair treaties regarding land.

In the French & Indian War, the bulk of tribal support falls on the side of France. Lasting ill will also flows from scalp-taking atrocities, most notably by the Huron against the British colonists exiting Ft. William Henry in August 1757. (This event is memorialized in James Fennimore Cooper’s popular 1826 novel, The Last of the Mohicans.)

Tribal Involvement: French & Indian War

| Years | Support Britain | Support French |

| 1754-60 | Iroquois, Catawba, Cherokee | Algonquin, Delaware, Ojibway, Ottawa, Shawnee, Huron, Abenaki, Micmac |

As more American settlers infringe on their homelands, tribal support leans toward the British during The Revolutionary War. Iroquois attacks in the Mohawk and Susquehanna valleys are particularly vicious and are long remembers by men like George Washington who will later exact his revenge.

Tribal Involvement: The Revolutionary War

| Years | Support Americans | Support Britain |

| 1775-81 | Oneidas, Tuscoraras, Mohicans, Potawatomie, Delaware | Iroquois, Shawnee, Cherokee, Creek, Miami, Huron, Cayugas, Seneca, Mohawk, Onondagas |

Once the war ends with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Britain cedes all of their land west of the Appalachian Mountains to the U.S. with no consultation with the tribes and no consideration for the fact that it is home to many of those who fought alongside them.

From there, the immediate future of the Native Americans lies with George Washington. As Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, he has courted military support from a host of tribes, with both successes and failures. Like other early U.S. Presidents, Washington is conscious of the native’s prior presence in America and in some ways he respects this. He elevates their status as sovereign nations apart from the U.S. for legal purposes, and expresses his wish that farming might take hold in their culture and facilitate peaceful relations in time.

The Seizure Of Tribal Lands Begins

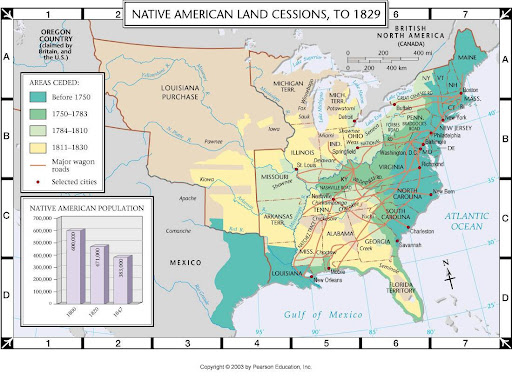

But Washington also initiates the process of completing “land cessions” between the tribes and the United States. These are not only applauded by the pioneers, but also provide a needed source of sales revenue to operate the government.

The tone is set in 1784 with the Treaty of Ft. Stanwix in New York. It forever reduces the influence of the Iroquois by surrendering eastern land, all claims in the Ohio territory and along the Niagara River, plus a wide swath in Pennsylvania. Seneca Chief Cornplanter signs for the Iroquois, but its full Tribal Council refuses to agree. Despite that, the treaty stands.

Focus now turns to the British forts that remain in place across the Northwest Territory after the official end of the Revolutionary War, some in tribal hands.

One is Ft. Sackville near present day Vincennes, Indiana, manned by some 325 Shawnee and Odawa warriors along with a lesser number of redcoats. In February 1779, the Americans, under Lt. Colonel George Rodgers Clark of the Virginia Militia, successfully siege the fort and thus gain control over the Illinois Territory.

As American settlers move westward after the Revolutionary War, pressure increases on the tribes to cede their homelands in exchange for the promise of annual annuities. Between November 1785 and January 1786, three separate treaties are signed at Hopewell Plantation in western South Carolina. Together the so-called “Treaty of Hopewell” transfers land in portions of Carolina, Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi from the Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples to the federal government.

The tribes, however, enjoy a significant victory in October 1790, led by Miami Chief Little Turtle and the Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket. Acting as the “Northwest Confederacy,” they engage a U.S. force of some 1400 troops under General Josiah Harmer, sent to punish the natives for raids on white settlers around the present day Ft. Wayne area. But the Americans walk into a series of clever ambushes and finally retreat after suffering 370 casualties.

The defeat of the “Harmer Campaign,” enables the Confederacy to add more tribes:

Tribes In The “Northwestern Confederacy” In 1794:

- Shawnee

- Miami

- Ottawa

- Odawa

- Mohawk

- Wyandot

- Delaware

- Potawatomie

But their raids in the Ohio Valley are stifled on August 20, 1794, when the Battle of Fallen Timbers ends with a decisive U.S. victory. The fight matches Revolutionary war hero “Mad Anthony” Wayne and his 3,000 troops against some 1300 natives led by Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket, Little Turtle of the Miami, and the Ottawa Chief Egushawa. The Americans control a high ridge that forces the tribes back against the Maumee River, and after a one hour fight, they flee toward the British compound at Ft. Miami. Once there, however, they are turned away by Major William Campbell who wants nothing to do with a battle against America.

Three months after Fallen Timbers, another treaty is signed that impacts tribes who have aligned with the British. It is the Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation (the “Jay Treaty”) signed on November 19, 1794, by U.S. Secretary of State, John Jay, and Britain. It ends warfare between the two nations over the next fifteen years, much to the dismay of the French. The British also agree to abandon all of their local forts, some of which end up in tribal hands.

A major land cessions follows on August 3, 1795, when General Wayne and the Northwestern Confederacy sign the Treaty of Greenville. This transfers nearly 17 million acres and secures the Ohio Territory for the U.S. along with other parcels to the west. Miami Chief Little Turtle agrees to the treaty, while Shawnee Chief Tecumseh opposes it and vows to resist. George Washington signs the deal and the Senate ratifies it on December 22, 1795.

Between 1804 and 1809 General William Henry Harrison, Governor of the newly created Indiana Territory negotiates three more significant agreements:

- The 1804 Treaty of St. Louis with the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes involving land in Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Missouri.

- The 1805 Treaty of Grouseland with the Miami ceding a modest parcel in southern Indiana.

- The 1809 Treaty of Ft. Wayne gaining more southwestern Ohio acreage from the Delaware And Miami tribes.

While popular with the public, Harrison’s acquisitions prove controversial in Washington since he attempts, but fails, to sanction slavery across Indiana in violation of the 1797 Northwest Ordinance.

By 1810, these various treaties have given the U.S. government control over a large portion of the tribal lands that were in British hands prior to the Revolutionary War. But two sizable areas remain in dispute: the upper Midwest, where a new confederation opposing the treaties has formed; and the deep South, where the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” remain strong.

The presumptuous term “civilized” is based on European standards which applaud the Cherokee for western style “advances” such as having their own formal government, their own written language, a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, and beginning to farm and to convert to Christianity.

The War of 1812 Triggers More Warfare With The Tribes

The start of the War of 1812 further upsets America’s relationship with the tribes.

Beginning around 1805, America is drawn into the renewed global conflict between Britain and France, now under control of Napoleon Bonaparte. The spark involves actions by the Royal Navy to strengthen its under-manned warships, which are critical to Britain’s strategy. To do so, it stops U.S. ships at sea and forcefully “impresses” American sailors. This leads to bloodshed in 1807 as the USS Chesapeake is bombarded off Norfolk, Virginia, by HMS Leopard with 21 casualties and four men impressed.

Napoleon then cons President Thomas Jefferson into suspending trade with Britain in 1810, which seems to suggest a U.S. alliance with the French.

Tensions continue to rise, and on May 1, 1811, the HMS Guerriere impresses another sailor after stopping the USS Spitfire off the coast of New Jersey. On May 16, the USS President responds by attacking the HMS Little Belt near North Carolina, with 11 British sailors killed and 21 others wounded.

These conflicts at sea are reinforced by reports that the British are also fostering renewed tribal uprisings against America. This in fact is the case, as Shawnee Chief Tecumseh seizes the moment to try to restore the tribal lands, traditions and way of life from “the Great Father” in Washington, whose promises seem to vanish when the time comes to deliver. He begins his campaign, focusing on the Indian land ceded in Indiana and Ohio.

In 1810 Tecumseh meets with Indiana Governor Harrison and promises loyalty to America if the territories are returned. But his younger brother, Tenskwatawa, known as “Prophet,” proceeds on his own to step up harassment of local settlers in southern Indiana. Harrison responds by leading 1,050 U.S. regulars and militia to confront Prophet, whose force comprises some 600 Miami, Potawatomie and White Loon warriors.

On November 6, 1811, Harrison encounters a tribal delegation under a white flag of truce near Prophetstown, at the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers. The two sides talk briefly and agree to meet again the next day.

With Tecumseh away in the southwest, seeking to recruit more support from the Cherokees, Prophet rejects the planned truce talks and decides in favor of a surprise attack on Harrison’s camp. At 4AM on November 7, war whoops ring out over the U.S. troops huddled just east of Burnett Creek. The battle rages for two hours, with the shocked Americans falling back initially, and suffering heavy casualties. But, unlike Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa is more the religious leader than the warrior. So Harrison is able to rally his troops, break out of his initial trap, and eventually burn Prophetstown to the ground. The Prophet survives the battle, but his credibility as a leader ends for good.

This victory at Tippecanoe insures national fame for William Henry Harrison who has successfully defeated both the hostile tribes and their British allies. But the truth is

more modest than the legend. Actual losses for each side on November 7 total only 100 fighters, and the outcome essentially ends all hope for a possible alliance against Britain between Tecumseh and the Americans.

As was true in 1775, the War of 1812 again forces the tribes to declare loyalty to one side

or the other and again the scales tilt in favor of the British.

Tribal Involvement: The War of 1812

| Years | Support U.S. | Support Britain |

| 1812-5 | Oneidas, Cherokee, Delaware, Friendly Creek | Shawnee, Mohawk, Fox, Chickamauga, Sauk, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Red Stick Creeks, Ojibway |

Tecumseh’s Death Ends The “Northwestern Confederacy”

The decisive contest for Tecumseh’s Northwest Confederacy comes on October 5, 1813 at the Battle of the Thames, some 75 miles east of Detroit.

Once Admiral Oliver Hazzard Perry defeats the Royal Navy on the lake in September 1813, the British are forced to retreat from their stronghold at Ft. Detroit.

The redcoats make their way to the Thames River which runs parallel to the northern edge of Lake Erie. Along the way, Tecumseh convinces the British commander, Major General Henry Proctor, to make a stand at Moraviantown, near a Delaware settlement. Proctor’s force consists of some 800 half-starved and recently defeated Regulars along with Tecumseh’s contingent of 500 mostly Shawnee warriors.

Chasing after is General Harrison’s overwhelming force of 3700 men. On October 4 they catch up to the British rearguard and overwhelm it near the town of Chatham. On October 5, Proctor sets up a nearby line of defense with his right flank along a swamp and his left on the Thames River. He has one cannon at his disposal and no entrenchments. Harrison surveys the enemy position and orders a mounted frontal assault commencing shortly after daybreak.

The redcoats respond with one fusillade before fleeing from the field along with Proctor.

Not so the native warriors who fight on until their leader Tecumseh is killed, after which they are demoralized and disperse through the swamps.

Reported casualty figures vary widely, but Harrison claims 72 redcoats killed and another 22 wounded and captured. Shawnee losses range from 17 to 33, while the figures for the Americans are 10-20 killed and another 30-50 wounded.

Tecumseh is 45 years old when he dies and soon becomes the stuff of legends. General William Tecumseh Sherman will bear his name, and Colonel Richard Mentor Johnson becomes Vice-President based in part on his claim to have killed the Chief during the battle. Future President William Henry Harrison also earns his most important victory, not at Tippecanoe, but along the banks of the Thames.

Andrew Jackson Attacks Two Tribes In The South

Tecumseh’s death marks the end of tribal hope to reverse their treaty cessions of land in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. All that remains in contention then are the territories of the “Five Civilized Tribes” scattered across Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas.

The So-Called “Five Civilized Tribes” In 1812:

- Cherokee

- Choctaw

- Chickasaw

- Creek

- Seminoles

Of the five, only the Seminoles and one branch of the Creeks fight alongside Britain. The most famous confrontation takes place on March 27, 1814 along the Tallapoosa River in southern Alabama at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

The “Red Stick” Creeks – named after their crimson painted war clubs – have been recruited by Tecumseh and conduct raids on settlements in Florida. The most savage occurs in August 1813 at Ft. Mims, 50 miles north of Mobile, where 250 defenders are massacred. Calls for military help are answered by Governor Willie Blount of Tennessee who chooses General Andrew Jackson to lead troops down the Coosa River into Creek territory.

Jackson’s force includes 2,700 militia and 600 Cherokee, Choctaw and “Friendly” Creek. In March 1814 he swings east from the Coosa to confront the Red Sticks camped in a horseshoe-shaped loop of the Tallapoosa River.

While the Creeks feel safe surrounded by the river, the fact is that they are trapped in a cul du sac, with only one narrow pathway in and out over open ground. When the Red Sticks throw up breastworks to defend this camp entrance, Jackson attacks it repeatedly with artillery and charges and also sends probes across the river into their rear. After five hours of battle, the Creeks disintegrate, with upwards of 80% of their number being killed, wounded or captured. In addition to Jackson, two other American fighters – Sam Houston and Davey Crockett – win glory from this fight.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend ends the Red Stick resistance, and on August 9, 1814, the Nation ceding 23 million acres of land to the United States in the Treaty of Ft. Jackson. This comprises parts of southern Georgia and central Alabama.

But Jackson’s mission against rebellious tribes is not finished. In December 1817 he is ordered by the War Department to “bring the Seminoles under control.” This will take him into Florida which remains in the hands of Spain, even though its control over the tribes is minimal.

On March 15, 1818, Jackson sets out for East Florida from Ft. Scott with a mixed force of some 4200 regulars, militia and friendly Creek Indians. Moving south down the Apalachicola River, he pauses to construct a new stronghold, Ft. Gadsden. He then swings back up north and east, assaulting and burning a Seminole village at Tallahassee on March 31, and taking the town of Miccosukee the following day.

The General’s next destination is San Marcos de Apalache, a port city on the Gulf of Mexico, home to the Spanish Fort of St. Marks. There he tries and executes two British nationals, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, who are rumored to be selling guns to the Indians.

After a sweep further east along the Suwanee River, Jackson feels he has accomplished his mission, and heads back west, first to Ft. Gadsden and then into West Florida, were he reduces the Spanish Ft. Barrancas at Pensacola on May 28.

This ends Jackson’s ten week rampage across northern Florida.

It is followed, however, by a barrage of criticism from Spain, and also back in Washington where Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, assails Jackson as a rogue actor and tries to have him censured by Congress. (Thus begins a lifelong feud between the two men that is amplified when Clay uses his power in the House to hand the stalemated 1828 election to John Quincy Adams over Jackson, who has lead in the popular voting.)

Demands For Tribal Lands Accelerate

Once the War of 1812 ends, demand accelerates to physically remove the tribes from the lands they have ceded in order to make way for the white settlers from the east.

One of the first initiatives involves the state of Georgia where the Treaty of Indian Springs is approved one day before JQ Adams becomes president in 1825. The terms have supposedly been worked out between chiefs of the Creek and Cherokee tribes in Georgia and two U.S. Commissioners – with the Indians ceding their lands in Georgia and Alabama in exchange for equal acreage in the west and a cash bonus of $400,000. September 1, 1826 is set as the deadline for the tribes to move west.

But the deal is fraudulent, top to bottom, the work of only one Creek leader, John McIntosh, and Georgian officials eager to line their own pockets. When McIntosh is murdered by rival chiefs for his betrayals, the matter comes to Adams’s attention.

The President’s response is indecisive.

Even though he has signed the Treaty, he is troubled by the reports of fraud, and orders a halt to state land surveys scheduled to start sixteen months hence. This triggers a violent response from Governor George Troup of Georgia, who threatens to defy the President and begin the survey at once. At this point General Edmund Gaines is dispatched to investigate further. He sides with the Indians and reports that Troup is a “madman.” In turn, Adams signals Troup that U.S. military forces are to be used against any attempt by the state to enter the lands.

After Troup backs off, Adams tells the Creeks that Congress is unlikely to deny the original Treaty unless it can be replaced with a new one involving a land trade. The tribes meet and offer an option, but Adams tells them their proposed boundaries are unacceptable. Adams turns to his Cabinet in search of a solution.

Secretary of War Barbour argues for gradual diffusion of the Indians rather than any mass exodus, in hopes of seeing them assimilated into white civilization. Henry Clay finds this impractical, saying that the Indians, like the Africans, are an inferior race, and will never be successfully integrated.

Senator Howell Cobb of Georgia, a rising southern spokesperson, tells Adams that his state will henceforth support Andrew Jackson unless he acts immediately to enforce the original treaty. In characteristic fashion, Adams fires back at Cobb:

We could not do so without gross injustice. As to Georgia being driven to support General Jackson, I feel little care or concern for that.

After more pressure from Adams, the Creeks agree on January 24, 1826, to the Treaty of Washington, which it cedes more, but not all of their Georgia lands and sets a precedent whereby the U.S. officially recognizes the Indian tribes as “sovereign nations.”

Adams forwards the new Treaty to the Senate, but Governor Troup says that he plans to start surveying the land immediately, on the grounds that…

Georgia is sovereign on her own soil.

(This is the same spirit of “nullification” of federal mandates that will become popular among states’ rights advocates across the South.)

Clay urges Adams to send federal troops in to force Troup’s hand, but the President opts to push the Creeks once again to surrender more territory. And they do. On November 13, 1827 they cede their remaining land in Georgia in exchange for another $42,000 and a promise that the government will protect them as they move west — a promise ignored when the time comes.

Not only has JQ Adams alienated Georgians and looked weak throughout the negotiations, he also concludes, in hindsight that he has violated his own ethical standards along the way.

These (treaties) are crying sins for which we are answerable, and before a higher jurisdiction.

Andrew Jackson Orders The Forceful Removal Of The Eastern Tribes

No such qualms appear after Jackson is elected as America’s seventh president in 1828.

By the time he enters office, the wheels have already been set in motion to allow white settlers to usurp the lands of the southeastern Indian tribes – with the stampede heightened by the discovery of gold at a mine in Dahlonega, Georgia.

On December 28, 1828, the Georgia legislature passes a law transferring ownership of all Cherokee territory to the state without any signed treaty.

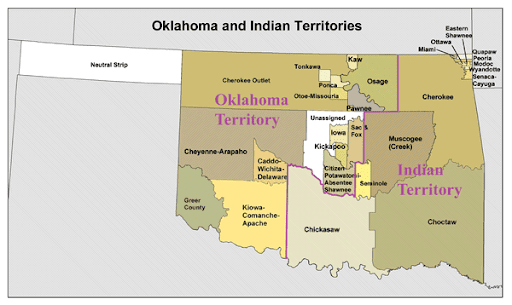

But the Indian Removal Act of May 1830 barely passes congress, with the North opposing it and the South vigorously in support. This Act calls for forced transfer of the “civilized tribes” from the southeast to their new reservations west of the Mississippi in the Oklahoma territory.

The contrived rationale for the Removal Act is that relocation will give the natives an even better chance to master agriculture and “become modernized” in their ways. Also the claim is made that reimbursements in land or cash will be offered to those displaced.

The legal system now enters into the picture.

In June 1830, Chief John Ross, backed by Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, seeks an injunction in federal court to stop “the annihilation of the Cherokee tribe as a political society.” His argument is based on the notion that the Cherokees are a “foreign nation” – and, as such, not subject to Georgia’s jurisdiction or laws.

On March 18, 1831, the U.S. Supreme Court under John Marshall dodges the central issue in favor of a procedural ruling in Cherokee Nation v Georgia.

By a 4-2 vote, the decision says that the tribes, like the Africans, are not American citizens and therefore have no “standing” or guaranteed rights in the United States, including appeal to its courts. Despite strong dissent from Justices Story and Thompson, Marshall defines their status as that of “a ward to its guardian.”

In this case the “guardian” is Andrew Jackson who is eager to act against the Native Americans. In 1831 he orders General Winfield Scott to begin the “removal” process, using regular U.S. Army troops and local militia where needed.

A few tribes decide to resist, the most famous being the Sauk in northwestern Illinois.

The Blackhawk War Of 1832

In 1832 the Sauk Chief, Black Hawk, tries to build a confederation of resisters similar to what the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh achieved in 1811, back east in the Indiana Territory.

Black Hawk is 65 years old at the time. Since his youth he has fought against the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis which surrendered some 5 million acres of his homeland, mostly in the southern Wisconsin/Michigan Territory. During the War of 1812, the British name him a Brevet Brigadier General, and his Sauk fight alongside the Crown to stem the tide of white settlers.

But by June 1831, it seems apparent that his battle is lost, and Black Hawk leads his villagers west across the Mississippi into the “unorganized territory.”

Ten months later he changes his mind and convinces his Sauk tribesmen to re-cross the river and reclaim their ancestral lands. To assemble a credible fighting force he seeks support from a variety of other local nations, including some Kickapoos, Meskwakies, Fox, Ho Chunks and Potawatomie. Together they hope to form what will be known as the “British Band,” given their historical linkage to the redcoats.

On April 6, 1832, the British Band of roughly 1,000 Sauk warriors and their families crosses the Mississippi and heads northeast along the Rock River toward the southern border of Wisconsin.

By May 14 they have travelled 90 miles and reached Old Man’s Creek, without being joined by any of the allies they anticipated. When they encounter Illinois militia under Major Isiah Stillman, Chief Black Hawk is ready to abandon his quest. He sends white flag emissaries to signal his intent, but they are fired upon. The fight which ensues finds the Sauk routing the undisciplined militia in what goes down sarcastically as the Battle of Stillman’s Run.

With this victory, Black Hawk is encouraged to continue his quest, while a humiliated Governor Duncan of Illinois call up a force capable of putting down the rebels.

Over the next ten weeks, Black Hawk fights a series of skirmishes while swinging through southern Wisconsin and eventually retreating toward the Mississippi. On July 21 the Battle of Wisconsin Heights is fought in Dane County, with remnants of the British Band slipping away to the west. Twelve days later the Black Hawk War ends at the Battle of Bad Axe, where US troops under General Henry Atkinson and Major Henry Dodge wipe out the remaining rebels.

Chief Black Hawk himself is captured and sent to Washington D.C., where he meets with the President before being sent to jail for a short time. There he tells his life story to a reporter who turns it into a biography, making him a celebrity until his death in 1838.

The war which bears his name is also remembered for two famous participants who play cameo roles. One is 23 year old Abraham Lincoln, living in New Salem, Illinois, and working as a clerk in a village store, when he enlists in the Illinois militia. He serves for roughly 12 weeks, mainly as Captain of a rifle company in the 31st Regiment out of Sangamon County. Lincoln sees no combat during the war, and later jokes that his greatest challenge was fighting mosquitoes.

The other is 24 year old Jefferson Davis, graduate of West Point in 1828 and in the Regular Army as a second Lieutenant, stationed at Ft. Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Davis is in Mississippi on furlough during the conflict, but is later assigned to escort Chief Black Hawk to Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis.

Recap Of Early Tribal Battles

| Year | Battle of… | In | Key Tribes | Outcome |

| 1779 | Ft. Sackville | Ind | Shawnee/Odawa | U.S. wins control over the Illinois Territory |

| 1790 | “Harmer” | Ind | Shawnee/Miami | Tribes defeat General Harmer’s campaign |

| 1794 | Fallen Timbers | OH | Shawnee/Miami | General Wayne over Blue Jacket/Little Turtle |

| 1811 | Tippecanoe | Ind | Shawnee | Harrison defeats “Prophet” |

| 1813 | Moraviantown | OH | NW Confederation | Tecumseh killed and Confederation collapses |

| 1814 | Horseshoe Bend | Ala | Red Stick Creeks | An early Andrew Jackson victory |

| 1818 | Tallahassee | Fla | Seminoles | Jackson rampages across Florida |

| 1832 | Bad Axe | WI | Sauk | Chief Black Hawk retreats to reservation |

The “Trail Of Tears” Suffering Is Under Way In 1832

Just as Jackson acts to remove the remaining eastern tribe to the western “reservations,” a new decision by the Supreme Court in Worcester v Georgia appears to frustrate his plan.

The central question here comes down to whether the state of Georgia can dictate the removal of the Cherokees from land they have not ceded to the federal government in prior treaties.

The answer, by a solid 5-1 ruling of the Marshall Court is that such a move is unconstitutional – since the tribes are “sovereign nations” and, as such, only the federal government has the power to negotiate with them on regulating their territory.

Associate Justice Joseph Story expresses relief at the time that justice has finally been served:

Thanks be to God, the Court can wash their hands clean of the iniquity of oppressing

the Indians and disregarding their rights.

But the High Court is reluctant to declare penalties for skirting the ruling for fear of further enflaming opposition among individual states like Georgia.

Andrew Jackson seizes upon this reluctance and issues his verdict on the court’s call:

John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!

The President is, however, sufficiently alarmed by the ruling to meet with John Ridge, son of a Cherokee chief, educated at the Foreign Mission School in Connecticut, and acting as counsel for the tribe in Washington. Jackson assures Ridge that he does not intend to use military force in Georgia, but encourages him to work out a formal treaty to resolve the issue.

Ridge and a minority set of elders proceed to negotiate the Treaty of New Echota, by which the tribes agree to abandon the land and move to the “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma. It is signed into law on December 29, 1835, despite opposition from Principal Chief John Ross and the full Cherokee Council. (Four years later, both John Ridge and his father will be assassinated for betraying the tribe’s heritage and culture.)

What happens next is what Cherokee lore calls “the trail where they cried” – latter translated into “The Trail of Tears.”

Across the South, a total of some 120,000 people from the “five civilized tribes” are forced to leave their ancestral and sacred homelands for the new “Indian Territory.” Up North, another roughly 90,000 Indians are herded into concentration sites from Memphis to Cleveland, and then transported by wagons and flatboats across the Mississippi to their new reservations.

Estimates of death from hardship or disease during the exodus run from 15-25% of those in transit. But in the end, Jackson and the settlers have the land they sought.

The pillage that Jackson initiates against the tribes will continue largely unabated for the next six decades.

As such, it stands alongside slavery as one of the lasting stains on the soul of the nation.

In 1836 General Winfield Scott drives the remaining Creek resisters in Alabama off their lands; in 1837 he turns to the Choctaws in Mississippi, and in 1838 he leads a force of 7000 troops against the Cherokees in North Carolina. By 1842, after an expense of nearly $20 million, the wars against the Seminoles are concluded.

Key Events Related To The “Indian Removal” From Their Eastern Homelands

| Nations | Ancestral Home | “Trail of Tears” |

| Choctaw | Mississippi | About 17,000 moved in 1831, with 3-6000 killed along way. About 5500 stay in Mississippi and agree to “follow the law,” but the white settlers constantly harass them. |

| Creeks | Alabama | Most moved in 1834, with Scott completing the job in the Creek War of 1836. |

| Chickasaw | Mississippi | They are concentrated in Memphis in 1837 then driven west and forced to join the Choctaws Nation, until later regaining independent status. |

| Cherokee | North Carolina | In 1838 Van Buren sends Scott to round up all Cherokees in concentration sites in Cleveland, then drives them west. The Cherokees survive well and their population grows over time. |

| Seminoles | Florida | The Seminole Wars run from 1817 to 1842, at high cost and with renegade bands finally taking refuge in the Everglades. |

As America’s borders shift into the Louisiana Territory and beyond, local tribes will again be forced to move from the homes to accommodate the white settlers, often backed by the U.S. Army.

Further U.S. Moves Against The Native Americans In The West

| Nations | Home | Conflicts |

| Comanches, Kiowa Apaches | Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico | From 1836 to 1875 Anglo settlers battle to settle on tribal lands in the Comancheria. The 1858 Battle of Antelope Hills signals the decline of the resistance. In 1875 the Comanches are forced into space set aside for the southeastern tribes in Oklahoma. The Apaches settle further west in Arizona. |

| Eastern Dakotas | Minnesota | In 1862 US troops under General John Pope defeat eastern Sioux tribes along the Minnesota River and hang 38 captives in Mankato. |

| Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne | N/S Dakota, Montana | Lakotas pushed aside after gold discoveries in the Black Hills. Sioux victory at the Little Big Horn leads to US troops crushing remaining rebels. |

In the end, the fate of America’s native peoples has much in common with that of the Africans. Both populations are treated poorly, the Africans enslaved in chains, the Tribes confined to their “reservations” and to poverty.

Main Treaties Ceding Tribal Lands East Of The Mississippi River

| Year | Treaty of… | Where | Key Tribes | Land Ceded (Parts of…) |

| 1784 | Ft. Stanwix | NY | Iroquois/Seneca | New England, Ohio, Pennsylvania |

| 1785 | Hopewell | SC | Cherokee/Choctaw | South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Miss. |

| 1795 | Greenville | OH | NW Confederacy | Ohio |

| 1804 | St. Louis | MO | Sauk | Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri |

| 1805 | Grouseland | Ind | Miami | Southern Indiana |

| 1809 | Ft. Wayne | OH | Miami/Delaware | Southwest Ohio |

| 1814 | Ft. Jackson | Ala | Red Stick Creek | Georgia, Central Alabama |

| 1825 | Indian Springs | Ga | Creek/Cherokee | Georgia, Alabama |

| 1835 | New Echota | Ga | Cherokee | Northwest Georgia |

Reflections On The Treatment Of Native Americans

In hindsight the tragic fate of the tribes seems inevitable given the gap between their culture and traditions and those of the European interlopers.

This did not seem so in the beginning when, according to the later day philosopher, Henri Rousseau, the natives seemed to possess “all the virtues that resonate with the American spirit:”

These are truly free men, not slaves, living independently off the land,

governed by the communal will of their tribe.

This too is the image painted by the novelist James Fennimore Cooper in the “noble savages,”

Chingachgook and Uncas, the loyal Mohican companions of the frontiersman, Natty Bumpo.

And indeed, most Native Americans greeted the white settlers in peace, helped them navigate the new territory, and sought favorable relations. Despite the fact that the Europeans brought with them new infectious diseases that reduced the tribal population at the same time that their own numbers were growing rapidly.

But at first land was plentiful and skirmishes over it were rare.

Then came the French & Indian War (1754-60) where the majority of tribes ended up fighting against Britain and the colonial settlers. When this pattern continued into the Revolutionary War (1775-81), relationships soured, with certain tribes now regarded as ongoing enemies of the United States.

The early American presidents seemed as conflicted about tribal relations as they did about chattel slavery. Several discussed the matter in Inaugural Addresses, always asserting their sense of obligation to “those who were here first” and hope for their peaceful assimilation, while recognizing the challenges involved. Here is Thomas Jefferson in 1805:

Humanity enjoins us to teach (our aboriginal inhabitants) agriculture and the

domestic arts; to encourage to that industry which alone can enable them to

maintain their place in existence…. But the endeavors to enlighten them… have

powerful obstacles to encounter.

And then James Monroe twelve years later, after some tribes again side against the Americans in the War of 1812:

With the Indian tribes it is our duty to cultivate friendly relations and to act with

kindness and liberality. Equally proper is it to persevere in our efforts to extend

to them the advantages of civilization.

But with the carrot came the stick: for the tribes to survive and thrive they must stop consorting with foreign enemies and adjust their beliefs and way of life to conform to the American norms.

To insure this outcome, they must depend on the “Great White Father” in Washington to oversee their future.

As time passes and conflicts over land accelerate almost all semblance of good will vanishes. Then comes the tribes’ worst enemy, President Andrew Jackson, who initiates their forceful removal from their ancestral homelands with The Trail of Tears.

As so often the case, it is perhaps the French visitor to America, Alexis De Tocqueville, who best sums up the history of the Native Americans in his 1835 book, Democracy in America:

Amongst these widely differing families (in America), the first which attracts attention..

is the white or European, the man pre-eminent; and in subordinate grades, the negro

and the Indian. These two unhappy races have nothing in common; neither birth,

nor features, nor language, nor habits. Their only resemblance lies in their misfortunes.

Both of them occupy an inferior rank in the country they inhabit; both suffer from tyranny.

Oppression has been no less fatal to the Indian than to the negro race, but its effects

are different. Before the arrival of white men in the New World, the inhabitants of

North America lived quietly in their woods, enduring the vicissitudes and practicing

the virtues and vices common to savage nations… Far from desiring to conform his

habits to ours, he loves his savage life as the distinguishing mark of his race, and

he repels every advance to civilization, less perhaps from the hatred which he

entertains for it, than from a dread of resembling the Europeans.

The Europeans, having dispersed the Indian tribes and driven them into the deserts,

condemned them to a wandering life full of inexpressible sufferings. The moral and

physical condition of these tribes continually grew worse, and they became more

barbarous as they became more wretched.

Nevertheless, the Europeans have not been able to metamorphose the character of

the Indians; and though they have had power to destroy them, they have never

been able to make them submit to the rules of civilized society.

Postscript:

it was not until 1924 that Native Americans were granted citizenship in the United States. They were not allowed to vote in U.S. elections until 1965, and some states have continued to contest this outcome. As of 2020, their population count was 9.7 million or 2.9% of the nation’s total.