Section #2 - The Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War: 1775-1781

The Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War that breaks out in 1775 is unforeseen a decade earlier by both Britain and the Americans. The two have been partners for over 165 years and have just fought side by side in the French & Indian Wars of 1754 to 1758. And then the bond unravels.

Causes of the War

Ironically the British victory over the French in the Seven Years War (1756-63) leads to the rebellion. The trigger is the massive L130 million federal debt resulting from the war, and the Crown’s determination to pay it down, in part by raising taxes on its colonial subjects.

King George III, who ascends at age twenty-two in 1860, and Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Grenville, embark on a series of monetary squeezes in America, under the supposed aegis of “defending the colonies from future invaders:”

- The Proclamation of 1763 demands that any American families who have settled west of the Appalachian Mountains abandon their homes and return east – thus enabling Britain to sell back this land, won in the war, for a profit.

- The Sugar Act of 1764 adds taxes on sugar, coffee and wine, while prohibiting imports of rum and French spirits.

- The Currency Act of 1764 prohibits the colonies from issuing its own paper money, a move that tightens British control over all economic transactions in the colonies.

- In March 1765, the Stamp Act requires that a paid-for seal be affixed to all printed material – from legal documents and licenses to everyday items like newspapers, pamphlets, almanacs, and even playing cards.

Colonial anger over these acts is compounded because Britain simply dictates them without any input or debate from members of the locally elected House of Burgesses. When word of growing protests reach England, a defiant Parliament passes the Declaratory Act, stating that the Crown has the absolute right to impose whatever demands it deems appropriate.

The growing tension is relieved momentarily when the Stamp Act is repealed in 1766. But the period of calm passes in 1767 when a new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Charles Townshend, imposes a series of taxes on staples such as lead, paint, glass, paper and tea.

This provokes open resistance in and around Boston, with members of a “revolutionary body” known as the “Sons of Liberty “vowing to oppose collection of the new duties by boycotting the imports. Britain responds with a show of force — sending troops into Boston in 1768 to insure tax collection, and handing the bill for housing them to the colonists through a Quartering Act.

A sense of betrayal turns to violence on March 5, 1770, when a mob of protesters at the customhouse begin pelting British guards with stones. The redcoats fire into the crowd, killing five civilians and wounding seven. This March 5 event is christened “the Boston massacre,” and word of it spreads rapidly across the colonies. But again Britain backs off, with Prime Minister Lord Frederick North rescinding the bulk of the Townshend taxes.

This truce lasts until 1773 when a harsher new Tea Act interferes with local commerce by demanding that all sales of tea be handled by British agents of the East India Company rather than city merchants. Reaction comes quickly. On December 16, 1773, a “Sons of Liberty” band, poorly disguised as Mohawk Indians, climbs aboard British ships in Boston harbor and dumps 342 crates of tea into the water. The event is hailed as the “Boston Tea Party.”

The crisis now escalates rapidly. The Crown orders the port of Boston closed until the locals pay L15,000 to cover the cost of the lost tea. This “Coercive Act” is seen as a widespread existential threat and “Sons of Liberty” chapters spread beyond Massachusetts to New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania, eventually reaching all thirteen colonies. Meetings are held at “Liberty Trees” in town centers or local taverns, while newspapers and broadsides capture the growing antagonism toward the British occupiers.

In July 1774, Thomas Jefferson, a 34 year old Virginia planter and Burgess member, publishes a pamphlet, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, laying out grievances against the Crown and asserting that men have the right to govern themselves.

This is quickly followed by a First Continental Congress — a watershed moment for the colonists, and a precursor to the formation of a future independent and national government.

It is held at the two story Carpenter’s Hall guild house in Philadelphia over a seven week period beginning on September 5, 1774. Twelve of the thirteen colonies are present, with only Georgia missing. The Congress is presided over by Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses in Virginia, and comprises a total of 56 delegates, all elected by their local legislatures to speak for their colony’s interest. Among those present are many of the men who will shape America’s future: George Washington, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, Joseph Galloway, Roger Sherman, John Jay, Samuel Adams, John Rutledge and Richard Henry Lee.

The central debate occurs between those like the Virginian, Patrick Henry, who favor a clean break with England, and opponents, such Joseph Galloway, a Loyalist from Pennsylvania, who will ultimately join the British army. In the end, the majority agree to send a sharp message to the crown by imposing a boycott on all British imports to begin on December 1, 1774. This will not only reduce revenue flowing to Britain, but also signal the growing capacity of the colonies to manufacture the finished goods on their own.

On the question of actual independence, the decision is to take a wait and see stance for the moment, and then reconvene a second Congress on May 10, 1775 to revisit conditions at that time. The Americans now look to Boston to see what happens next.

The Shot Heard Round The World

Enter a new figure, Major General Thomas Gage, named on May 13, 1774, as Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. He has lived in America for almost 20 years and fought in the French & Indian War. He is on leave in England for the Boston Tea Party, but returns with orders to quell the rebellion.

Rather than resorting directly to force, Gage makes several attempts over the next year to stabilize the situation by forming local councils to resolve conflicts. But he becomes increasingly concerned about rumors that the Sons of Liberty are threatening violence against the Crown.

Two of their leaders, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, draw Gage’s ire, and he orders his troops to march 16 miles west toward the town of Concord, to arrest them and to seize their weapons. Around 10PM on the night of April 18, some 700 Infantry Regulars under Lt. Colonel Francis Smith depart Boston to carry out Gage’s directive.

Their plan to take the Americans by surprise is, however, foiled by one Paul Revere, a Boston silversmith, who doubles as an intelligence agent for the “Committee On Public Safety.” Revere learns of the planned British route – by boat across to the Charleston peninsula — and signals advance warning by having two lanterns (“one if by land and two if by sea”) hung in the bell tower of the Old North Episcopal Church. He then completes a “midnight ride” across the countryside to Lexington, awakening the “minuteman militias” along the way, before meeting up with Adams and Hancock who decide to make a stand against the redcoats.

The Revolutionary War begins at the village of Lexington, roughly ten miles west of Boston on the road to Concord. There, around 5AM on April 19, some 80 colonists exchange fire with British Regulars before driving them away with eight men killed and ten others wounded.

The red-coats regroup and march another six miles to the town square in Concord, which the local militia has abandoned in favor of higher ground, to the west. When a unit of roughly 90 British Regulars cross over the Concord River at the North Bridge, they are attacked and overwhelmed by 400 militiamen storming down from the hills.

The shocked and alarmed Lt. Colonel Smith decides to retreat from Concord around noon—but his movement is vexed by continuous harassment from the colonials, whose forces reach over 2,000 strong as the day wears on.

All that saves the Redcoats is a rescue contingent of 1,000 men under Earl Percy that meets them around 2:30PM in Lexington and opens cannon fire to momentarily stem the militia attacks. Still the skirmishing continues back to Boston, with the infuriated red-coats ransacking homes and stores along the way as retribution for their losses. By nightfall they are securely entrenched within the city, despite the remarkable assembly of some 15,000 armed militiamen who surround it by daybreak.

The battles at Lexington and Concord are no more than minor skirmishes when it comes to real warfare. But April 19 casts yet another die against any hope for reconciliation with Britain. And

the colonists have won their first organized battle with the mighty redcoats in what the author Ralph Waldo Emerson later calls The Shot Heard Round The World:”

By the rude bridge that arched the flood

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world

As word of the April 19 battle at Concord spreads, angry Virginians threaten to evict Governor Lord Dunmore for raising taxes, co-opting the militia to fight his personal battles with the Shawnees, and dissolving the House of Burgesses, a move which draws this memorable rebuke from member Patrick Henry, known as the “Son of Thunder,” in March 1775:

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?

Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give

me liberty, or give me death!

When Dunmore tries to deprive the militia of access to gunpowder on April 20, the move is denied by armed Virginians who claim ownership and threaten to storm the Governor’s Palace.

Dunmore responds by announcing his intent to impose martial law, free all slaves held by the rebels, and “reduce the city to ashes.”

Pleas for calm from George Washington and Peyton Randolph fail, and on May 2 a 150 man Hanover County Militia, serving under Patrick Henry, drive Dunmore and his family out of the palace and extract a L330 payment for the gunpowder from a wealthy Loyalist in town. This temporarily ends the conflict, with Henry off to attend the Continental Congress, and Dunmore hustled aboard the HMS Fowey before returning to England.

The Second Continental Congress Meets

On May 10, 1775 a Second Continental Congress convenes at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia to consider next steps. Twelve colonies are present (only Georgia being absent) and many of the prior representatives are joined by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

As with the 1774 convocation, two opposing factions are again evident: the Loyalists who seek to repair the breech with England and the Radicals calling for immediate independence. Each side registers wins and losses. For the Radicals, a Continental Army is sanctioned in case of a British invasion. The Loyalists gain agreement to a so-called “Olive Branch Resolution” to initiate negotiations with the colonial authorities.

A third contingent, however, is unwilling to wait. They are the so-called Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen, a founder of Vermont, and joined by Benedict Arnold of the Connecticut Militia. On May 10, 1775, their 200 raiders are 300 miles north of Boston at Ft. Ticonderoga, an important British stronghold in the French & Indian War. But it is essentially abandoned, and they “capture” it without firing a shot.

Meanwhile, General Gage concentrates his 6,500 redcoats on what is then the island of Boston, surrounded on all sides by rebel militiamen. This humiliation prompts King George to send three of his top generals to the colonies: the conspicuously courageous, but sometimes tardy Viscount William Howe; his second in command and often adversary, Henry Clinton, who grew up in New York City; and “Gentleman John” Burgoyne, aristocrat, playwright, rake and military man, ambitious for glory. They arrive in Boston harbor on May 25.

The Continental Congress counters on June 14 by naming George Washington as Commander-in-Chief over all American forces.

Washington and His Continental Army

Seventeen years have passed since Washington fought for Britain in the French & Indian War. But the lessons he learned will now serve him well: how to organize, train, supply and discipline his soldiers; to gain trust by leading from the front; to spot key lieutenants and delegate authority; to always look and act the part of one in charge, absent undue vanity.

But he has never actually commanded a large army before, and is well aware of the difference between disciplined British Regulars and the motley crew of some 16,000 Militiamen he inherits. They are short on weapons, gunpowder, training, even uniforms – with officers distinguished by colored ribbons pinned to their vests – pink for Brigadiers, purple for Major Generals, and blue for the Commander-in Chief.

While Washington will never be an accomplished battlefield tactician, he is superb as a strategist. He has an overall plan: keep his army intact, fight on through set-backs, and ultimately make the cost of the war – in blood and treasure – high enough that Britain finally walks away. Over the eight year course of the war, he makes remarkable escapes when necessary and launches surprise attacks that often change momentum.

He also becomes politically astute, extracting needed funds, often reluctantly, from Congress; training support from Prussia’s “Baron” Von Steuben at Valley Forge; and the crucial alliance with Lafayette and the French to win the war.

The Early Fighting Continues

When Washington arrives on the scene, his first priority lies in driving the British out of Boston by siege. To do so will require control over the high ground encircling the city. He already has command over Dorchester Heights south of the “Boston neck” and the area around Cambridge directly west of the city. What remains is the northern peninsula dominated by Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill. On June 17, some 1,000 troops under Colonel William Prescott set out to occupy Breed’s Hill which has a lower elevation but is nearer to the enemy. General Gage responds by sending 2,200 Regulars across the water to turn Prescott’s left flank, a move which fails at a cost of nearly 100 dead redcoats on the beach. A second wave is launched against Bunker Hill, but it too is turned back. By that time the rebels are almost out of ammunition and a desperate Howe sends a third wave directly up Breed’s Hill causing Prescott to flee and securing the northern heights for the British. But again the casualty scorecard – 1,054 redcoats vs. 440 rebels – reveals the American’s courage and determination.

When word of the losses reaches Britain, King George decides to replace Gage with General Howe. He follows this with a Royal Proclamation on August 23 labeling the rebels as “traitors” to their oaths of loyalty and to the Crown. This decree, along with the reckless naval bombardment of the town of Falmouth, Massachusetts, in October, further dampens any hope for reconciliation and strengthens the Radical’s call for independence.

While the stalemate in Boston drags on after Bunker Hill, Washington turns to his next priority, an invasion of eastern Canada. American General Philip Schuyler arrives at Ft. Ticonderoga on July 28. He sends second in command, Richard Montgomery, north along Lake Champlain and on November 14, the city of Montreal, with only a 150 man garrison, surrenders to him.

An Important Patriot Loss At Quebec City

Quebec City, a walled city on a 350 foot high promontory above the St. Lawrence Seaway, is the next prize in sight. Montgomery arrives on November 9 to find Benedict Arnold already there. But Arnold has lost almost half of his soldiers in a five week struggle across wilderness routes, and Montgomery’s troops are likewise worn out by travel in the harsh winter weather. Despite this, Montgomery is determined to assault the city and he follows the same path British commander Wolfe took in his assault during the French & Indian War. He reaches the same area west of the citadel on December 5 with roughly 900 men and begins his siege against General Guy Carlton’s 1,000 soldiers in the fort.

On New Year’s Eve, 1775, Montgomery decides to storm the fort from the left and right flanks during a heavy blizzard. Almost immediately Arnold suffers a shattered left thigh bone and is carted off the field, while Montgomery is killed on the right by grapeshot. General Daniel Morgan tries to rally the remaining troops as Carleton attacks, but surrenders the following morning. The American casualties total 60 killed or wounded and 426 captured; British losses are 5 killed and 13 wounded. Thus ends Washington’s quest for an easy victory in Canada.

Important Battles of the Revolutionary War In 1775

| 1775 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| April 19 | Lexington/Concord | Mass | Patriots | 400 | Shot heard round the world |

| May 10 | Ft. Ticonderoga | NY | Patriots | — | Green Mountain Boys |

| June 17 | Bunker Hill | Mass | British | 1500 | Boston’s northern heights to British |

| Oct 18 | Falmouth | Mass | British | — | Naval bombardment burns town |

| Nov 14 | Montreal | Canada | Patriots | ?? | Undermanned Montreal surrenders |

| Dec 31 | Quebec | Canada | British | 535 | Patriots abandon the citadel |

On January 1, 1776 the Royal Naval repeats the kind of terror campaign against civilians that occurred the prior October in Falmouth, Massachusetts. This time the target is Norfolk, Virginia, which is burned to the ground over three days by bombardments and infantry units.

The Redcoats Driven Out Of Boston

As winter progresses, the British still maintain their grip on the city of Boston, with the American siege nearing 8 months old. But just as they make plans to move toward their new base of operations in New York, the artillery Washington needs to defeat them makes a miraculous appearance.

The miracle is performed by 25 year old Colonel Henry Knox, who transports 54 heavyweight mortars and cannon from Ft. Ticonderoga some 300 miles, down Lake George and then overland, across the Berkshire Mountains, to Boston. The task is one of brute force, made doubly difficult by severe winter conditions, snow, ice and bitter cold. But, after a seven week trek, Knox and his guns, capable of a two mile range, reach Washington on January 27, 1776.

As the Americans wait for needed gunpowder, their engineers work secretly and silently to prepare batteries on Dorchester Heights. On the morning of March 5 the redcoats are stunned to see the new guns pointed at the city and the navy fleet. A confident Washington hopes that Howe will attack Dorchester and he initially plans to do so before a torrential downpour causes him to rethink. Instead, on March 8, he signals Washington that he will not burn Boston if he is allowed to leave unmolested. Washington accedes, and on March 17, some 120 craft carry 8900 troops and just over 2,000 women, children and Loyalists out to sea, headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

This is a celebratory moment for Washington, but it doesn’t last for long. On June 8, General Carleton wins the Battle of Trois Rivieres, driving the American troops out of Canada for good.

The Declaration Of Independence

The summer of 1776 marks fifteen months since the outbreak of fighting at Lexington – fifteen months in which the colonies have governed themselves, and roughly held their own in battle against the British Regulars.

Driven by these tailwinds, the “radicals” at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia are ready to force the issue of a final break with the Crown.

The move is reinforced by a widely circulated pamphlet titled Common Sense, written by Thomas Paine, formerly a disgruntled tax collector in Britain. Paine emigrates to Philadelphia in 1774 on the advice of Ben Franklin, with whom he shares a penchant for science, invention and journalism. He becomes editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine and soon takes up the cause of the American rebellion. Paine is a visionary, and his stirring rhetoric touches the colonists.

We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

On June 7, 1776, the Virginian Richard Henry Lee, who works hand in glove over time with John Adams of Massachusetts, offers a resolution to that effect.

Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Seven States immediately support Lee’s resolution, but six others waver – which leads to a three week hiatus as delegates return home for further local debate.

In the interim, the remaining delegates set up a series of “writing committees” to draft documents directed at gaining credibility and worldwide acceptance for a new nation.

First and foremost is a Declaration of Independence, assigned to a Committee of Five, including John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, who pens a first draft. The tone is restrained and appropriately respectful for an audience including the world’s hereditary monarchs – George III in England, Louis XVI in France, Charles III in Spain, Frederick II in Prussia – all of whom will be threatened by the content.

It begins with a statement of overall purpose – to explain why America is breaking away from the Crown.

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume…the separate station to which the laws of nature entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes..of the separation

From there it sets out a series of beliefs about the nature of man and of government. These beliefs ring out with bold Enlightenment assertions. That all men are born free, and that natural law endows each with an equal right to seek happiness. That the role of government is to support this quest. That the form of government is up to the will of the people and that they may change it any time it fails to meet their needs.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter and abolish it, and to institute new government laying its foundation on principles…most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

The Declaration then moves into a bill of particulars, in effect a formal indictment of the ways in which the King and the British government in the colonies have jeopardized the well-being of the citizenry. The list includes 27 separate counts, among them refusal to pass necessary statutes, obstruction of justice, imposition of taxes without consent, maintaining a standing army in times of peace, arbitrarily suspending local legislatures, cutting off trade with countries abroad, abolishing Charters, imposing martial law, “plundering our seas, ravaging our coasts, burning our towns, and destroying the lives of our people.”

All attempts at redress have failed, leading on to a conclusion:

A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant is unfit to be the ruler of a free people…We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America…declare that…these United Colonies…are free and independent States…absolved from all allegiances to the British Crown.

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.

With a final 1337 word Declaration in hand, a second vote is taken on the Lee resolution on July 2, with Pennsylvania and New York still hanging in the balance. When both vote “aye,” the motion passes, and the break with Britain becomes official.

Two days later, on July 4, delegates sign the formal Declaration of Independence and the new nation is born. Once this declaration is made public, Franklin tells his colleagues, “now we must, indeed, all hang together, or mostassuredly we shall all hang separately.”

A Crucial Defeat On Manhattan Island

In late June, reinforcements from Britain pour into Staten Island, swelling William Howe’s infantry to 32,000 Regulars and his navy, under his brother Richard, to 10 ships of the line, 20 frigates and hundreds of smaller vessels. Their intent is to capture Washington’s army on Manhattan Island.

When the astute General Charles Lee visits Manhattan in February 1776 he recognizes its vulnerability. It is effectively a 10 mile long military salient open on both flanks to assaults by British invaders from the East River and the Hudson River. Lee constructs a series of forts and batteries around the Island to lessen the threat, including Ft. George at the southern apex of the city. Still he warns Washington that a successful defense is unlikely and proposes immediate abandonment. This move, however, is rejected by the Continental Congress who regard the city as a symbolic capital for the new nation. Washington hears this and digs in.

He divides his 28,000 troops into five divisions: three around the lower tip of Manhattan; one 10 miles north at Ft. Washington; and one on Long Island to protect Brooklyn Heights.

Howe recognizes that the fortifications at Brooklyn are crucial to the American defense, since they dominate Manhattan’s flanks on the Hudson and East Rivers. If he can take them, he’ll transport troops up both rivers, send them inland to link up in a defensive chain, and bag Washington’s entire army before it can escape to the north.

On August 22 Howe lands about half of his troops on the southwest end of Long Island and moves toward Brooklyn Heights, accompanied by Generals Clinton and Charles Cornwallis who has just arrived from Britain. American General Israel Putnam comes out to meet them on August 27, but is surrounded and routed in the first truly sizable battle of the war. His men scurry back to their entrenchments on the Heights.

Washington recognizes the danger and crosses the East River along with 9500 men to personally lead the defense. Fortunately for him, Howe grows cautious. He pauses just long enough to allow Washington to execute a risky nighttime evacuation on August 29, ferrying 9500 troops across the East River from Brooklyn to Ft. George. Patriot losses on Long Island number 1,012 casualties to only 392 for Howe.

Now lower Manhattan becomes the trap that Howe has foreseen all along. But again he waits for over two weeks before striking. In the interim, Washington begins one of the great escapes that mark his military career. He moves the bulk of his forces north to Harlem, while leaving General Putnam to defend lower Manhattan.

General Clinton urges Howe to move faster and to land his redcoats north above Harlem to bottle up the Americans. Howe though is concerned about treacherous waters for his navy and settles on an amphibious crossing at Kip’s Bay on the east side of Manhattan around present day 42nd Street. The landing site is defended by roughly 500 Connecticut Militiamen, many armed only with pikes rather than muskets.

Around 11:00 on September 15, five warships unleash salvos which bury the American defenders in their trenches. Then some 80 flatboats land 4,000 Regulars under the command of General Clinton. Washington himself appears in the city with reinforcements, cursing the lack of resolve by the militia, and finally being led away for his own safety. Another 9,000 redcoats land and Clinton sends some south to capture the city and others west to cut off the escape routes to the north. But the latter move is not rapid enough and the bulk of Putnam’s division, guided by Captain Aaron Burr, successfully flee toward Harlem. The day ends with the British in control of lower Manhattan and with very few casualties. General Howe is delighted, while Clinton feels that a golden opportunity to win the war has been missed.

On September 16, skirmishes occur at Harlem Heights, but Washington’s defenses hold and the two armies remain stationary for the moment. On October 12, Howe initiates another attempt to surround the American army, this time further north. Anticipating the move, Washington takes two steps of his own. He shifts his main force of 14,500 men another ten miles up to White Plains where he suffers another defeat, on October 28. He also leaves behind some 6,000 troops to defend to strategic positions along the Hudson River: Ft. Washington on Manhattan Island and Ft. Lee across the river in New Jersey. Both fall on November 16.

On September 16, skirmishes occur at Harlem Heights, but Washington’s defenses hold and the two armies remain stationary for the moment. On October 12, Howe initiates another attempt to surround the American army, this time further north. Anticipating the move, Washington shifts his main force of 14,500 men another ten miles up to White Plains while leaving 6,000 behind to defend his strategic bastions along the Hudson River: Ft. Washington on Manhattan Island and Ft. Lee across the river in New Jersey. Neither action succeeds. On October 28 he is forced to flee from White Plains to Peekskill. On November 16, both Hudson River forts fall, with 2800 Patriots taken prisoner.

The Americans Make A 1776 Comeback At Trenton

The struggle for New York City has been a summer disaster for Washington, and with the winter of 1776 approaching he senses that the morale of his army, and his nation, is rapidly dwindling. His leadership is now on the line.

Once he realizes that Howe is no longer chasing him toward Peekskill, he swings his 5,000 troops west across the Hudson and then 110 miles south through Hackensack, Newark and Princeton, and over the Delaware River, just below Trenton. By December 8 his weary forces are camped there, facing across the river at a superior British army of 10,000 under Major General Charles Cornwallis.

The outlook is ominous, until Howe decides to end the campaign for the winter. Instead of attacking, Cornwallis departs from Trenton, leaving behind a small force of Hessians.

At this moment, Washington does the totally unexpected. On Christmas Day he decides to hurl his entire army across the Delaware against the Hessian rearguard. Washington’s plan to make two feints downstream is foiled by icy river conditions, but he himself leads some 2400 men to an upriver ferry and follows up with a devastating surprise attack which finds many of the Hessians asleep and intoxicated. Colonel Henry Knox’s artillery is particularly against the Hessian’s right flank. The result is a rout. The Hessian commander, Colonel Johann Rall, is killed, and 918 troops are forced to surrender. The Patriots follows this up with another victory at Princeton on January 2, 1777, then Washington decides to rest his fought out troops and prepare for the Spring.

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1776

| 1776 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Jan 1 | Norfolk | Va | British | ?? | Royal Navy bombs defenseless city |

| March 17 | Siege of Boston | Ma | Patriots | 1700 | British abandon Boston |

| June 8 | Trois-Rivieres | Quebec | British | 320 | Rebels chased out of Canada |

| Aug 27 | Long Island | NY | British | 2600 | Washington routed/escape Manhattan |

| Sept 15 | Kip’s Bay | NY | British | 380 | British control New York City |

| Sept 16 | Harlem Heights | NY | Patriots | 300 | Washington saves retreating army |

| Oct 28 | White Plains | NY | British | 500 | British chasing Washington |

| Nov 16 | Ft. Washington | NY | British | 3400 | 2800 isolated Patriots captured |

| Nov 20 | Ft. Lee | NJ | British | —- | Rebels retreat continues |

| Dec 26 | Trenton | NJ | Patriots | 950 | Washington surprises Hessians |

The Flamboyant General John Burgoyne Joins The Fight in 1777

Winter finds Howe resting his troop comfortably in New York City, while Washington is across the Hudson River from him in Morristown, New Jersey. In Canada, command of the northern army has been transferred from General Carleton to John Burgoyne who proposes a plan to drive down from Montreal, meet up with Howe around Albany, and isolate the rebellious New England states.

On July 5, 1777, Burgoyne takes Ft. Ticonderoga after American General Arthur St. Clair abandons it without a fight. St. Clair is subsequently court-marshalled and, though exonerated, is moved to the side.

But as Burgoyne proceeds down Lake Champlain toward Howe, his plan unravels. Instead of heading north up the Hudson to meet Burgoyne, Howe, his senior, decides to move south against the American capital at Philadelphia. Howe’s 18,000 troops exit Manhattan aboard frigates on July 23 for what becomes a month long voyage all the way to Chesapeake Bay, where they turn north to land at Elkton, Maryland on August 25.

Unaware of Howe’s movement, Burgoyne passes east of Saratoga on August 16 and engages a stubborn American force at Bennington, Vermont. The result is a bitter defeat with the British losing almost a thousand men before fleeing back west across the Hudson River. Not only has Burgoyne’s force shrunk below 6,000, but he now also learns that Howe is not coming to meet him. Early optimism is moving toward alarm.

Meanwhile Howe marches toward Philadelphia, and Washington comes out to meet him. The two armies clash on September 11 at the Battle of Brandywine, 30 miles southwest of the capital city. It is a bloody day-long fight that ends with successful flanking attacks by Howe which, as on Manhattan, threaten to envelope the Americans. Washington manages to escape and again Howe pauses rather than pursuing him. But with Philadelphia now likely to fall, the Continental Congress leaves on September 19 for Baltimore.

That same day, Burgoyne encounters rebel troop now under the command of General Horatio Gates some 14 miles southeast of Saratoga, New York. Gates has a strong entrenched position just above Bemis Heights, with the Hudson on his right and troops under General Benedict Arnold on his left. Burgoyne’s hope is to head through heavy forests to attack Arnold’s flank. To prevent this, Arnold finally convinces Gates to move his individual brigade or 1100 north toward Freeman’s Farm to intercept the redcoats. Success follows and Arnold signals Gates that, with just a few reinforcements, he could destroy Burgoyne’s entire army. After a shouting match between the two generals, Gates stays put and the British escape without further damage.

Back in Pennsylvania, Howe records another victory on September 20 just west of the capital at Paoli. At 1:00am the recoats fix bayonets to avoid the sound of gunfire and surprise “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s men in their tents. The outcome is known as the “Paoli Massacre,” but in truth is simply a one-sided rout. Howe then begins the siege of Philadelphia on September 26.

Washington feels compelled to defend the capital and attacks Howe on October 4 at Germantown, five miles north of the city. He divides his 11,000 troops into four wings and is making headway until a drunken General Adam Stephen’s brigade arrives late and out of line, then fires into their fellow Americans under Anthony Wayne. Washington is forced to retreat, then sacks Stephens, and turns his command over to a 20 year old Frenchman, Marquis de Lafayette. He is a former Captain of Dragoons in France and joins the Continental Army to seek revenge against Britain. His presence will prove profound.

Patriots Win The Pivotal Battle Near Saratoga

While Howe celebrates, Burgoyne is about to lose what most historians consider the key battle of the war at Bemis Heights. His troop count falls below 5,000; he is short of supplies; the heavily wooded terrain is baffling; Patriot General Gates remains well entrenched; and he has just been routed by Arnold seventeen days ago at Freeman’s Farm.

Still a desperate Burgoyne insists on another assault, this time on October 7, 1777. It becomes a replay of the prior battle, over the same ground north of Bemis Heights. His opponent this time will be General Benjamin Lincoln, after Gates relieves Benedict Arnold for ongoing belligerency. While Gates never budges from his entrenchment, Lincoln begins to push the redcoats back – at which point Arnold defies orders and rushes onto the field to rousing cheers from his men. He then leads a second rout of the British and German troops at Freeman’s Farm before receiving another serious wound to his left leg, shattered earlier at Quebec. Burgoyne flees to Saratoga before recognizing that his is a lost cause. He surrenders his army to Gates on October 9.

As for Benedict Arnold, he never forgives his treatment by Gates and the government. Surgery leaves him with a left leg two inches shorter than his right, and a permanent limp. He also marries into a Loyalist family and instead of being the “hero of Saratoga” he switches his allegiance to Britain in August 1778, passing coded messages to General Clinton in New York. When this plot is discovered, Arnold escapes, is named a redcoat Brigadier, and participates in British attacks before leaving America for London in 1781 as a traitor.

Back at Philadelphia, Howe begins a siege that will last for six weeks. The main obstacles in his way are Ft. Mifflin, located on Mud Island in the middle of the Delaware River and Ft. Mercer on the eastern bank. Together they cut off Howe’s supply lines and negate the power of the Royal Navy. Finally, after a six day bombardment, Ft. Mifflin falls on November 10. Ten days later, Ft. Mercer is abandoned, and Howe has won Philadelphia.

Washington is criticized for losing the capital, and he reacts with a not so veiled threat:

Whenever the public gets dissatisfied with my service…

I shall quit the helm and retire to a private life.

Suffering And Renewal At Valley Forge

Still he despairs over the deteriorating shape of his army as it enters winter quarters at

Valley Forge, 25 miles northwest of the capital. This brings a new recruit on the scene, Friedrich von Steuben. The self-styled “Baron” is 48 years old and out of work as a staff officer in Frederick the Great’s Prussian military when he encounters Benjamin Franklin in Paris and inquiries about service in the American army. He is hired on and sent to Valley Forge, arriving late in the winter and introducing the training and iron-willed discipline characteristic of the Prussian forces.

He begins by selecting the best 100 soldiers he finds to form a “model company,” then runs them over and over through basic drills. The 8 step/15 motions required to fire the standard 5’6” long flintlock musket, with accuracy and maximum speed. Marching formations and adjustments to maintain line integrity, respond to enemy maneuvers, and foster courage. Even the basics of camp sanitation and diet to sharply reduce illness such as dysentery and cholera. Another killer, smallpox, is controlled by inoculations. All accomplished to bursts of profanity in German aimed at slow learners. Once this “model company” takes shape, von Steuben

distributes his “graduates” among other units to clone the progress.

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1777

| 1777 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Jan 3 | Princeton | NJ | Patriots | 400 | British evacuate New Jersey |

| July 5-6 | Ft. Ticonderoga | Canada | British | 25 | St Clair abandons and is sacked |

| Aug 16 | Bennington | Vt | Patriots | 1000 | Burgoyne begins to face setbacks |

| Sept 11 | Brandywine | Pa | British | 1800 | Washington again escapes Howe |

| Sept 19 | Freeman’s Farm | NY | Patriots | 950 | Burgoyne’s first attack stopped |

| Oct 7 | Bemis Heights | NY | Patriots | 5750 | Arnold hero/Burgoyne army captured |

| Nov 10 | Philadelphia | Pa | British | — | Patriot capital falls |

Washington remains at Valley Forge from December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778. Supplies are scarce and 1700-2000 soldiers die over the winter. But with von Steuben’s guidance the rag-tag force now takes on a professional look and feel, and the Prussian is named Inspector-General for the Continental Army. New enlistments also expand the muster to 13,000 available men.

In the interim good news arrives in the form of more financial support from Congress and a major political and military development. Word of the British defeat at Saratoga prompts King Louis XVI to open negotiations with Benjamin Franklin to have France officially recognize and partner with the United States. This comes to fruition with the Treaty of Alliance in February 1778 which brings France into the war.

Britain Shifts To A “Southern Strategy” In 1778

This French entry has a profound effect on the view of the American war within the British government, led by Tory Prime Minister, Lord North. His Secretary of State for the Colonies, George Germain, searches for a strategy that will defeat the rebels while also protecting against France, both at home and in the Bahamas, Jamaica and other economically important West Indies possessions.

Germain’s “solution” is both radical and distorted by wishful thinking. It involves abandoning the Northern theater of the American War and shifting the focus to the South, where Germain hopes to rely on support from Loyalists who opposed the break with Britain all along. This move would put his army and navy closer to the West Indies, and also nullify the need to send more troops away from the homeland in case of French attacks there.

Germain’s plan is approved by Lord Jeffrey Amherst, hero of the French & Indian War in America, and now in command of all British forces worldwide. In turn, General Howe’s wish to return home is accepted and his second, General Henry Clinton, replaces him. New York will be maintained as Britain headquarters in America, but Philadelphia will be abandoned. When the departure occurs on June 18, some 3000 Loyalist residents choose to sail back to England.

Washington decides to harass the redcoats as they exit Philadelphia and move toward New York City. An advance division of 5,000 under General Charles Lee catches up with the rear guard of Clinton’s troops on June 28, 1778, just north of Monmouth Court House, New Jersey. But Lee botches his attack and is forced to retreat by Lord Charles Cornwallis until an upset Washington arrives to bail Lee out. The inconclusive battle ends when Cornwallis withdraws, but also with Lee court-marshalled for misconduct and removed from the army.

The action at Monmouth effectively closes the northern campaigns, except for a failed attack by the American infantry and a French fleet at Newport, Rhode Island in August. Washington will continue to maintain occasional pressure around New York, but the focus turns to the south.

The British priorities there are to gain control over the ports of Savannah and Charleston in order to ensure needed supplies and drive into the interior of Georgia and South Carolina. The campaign begins with redcoat raids across towns in Georgia in November 1778. General Clinton then orders Lt. Colonel Archibald Campbell and his 3500 troops to sail down from New York to link up with General Augustine Prevost’s division and plan a joint attack on Savannah. But when Campbell lands on December 23 at Girardeau’s Plantation 2 miles below the city, he decides to proceed on his own.

General Robert Howe is in charge of American forces across Georgia but with only 4 artillery pieces and 850 inexperienced militia. Still Howe moves out from Savannah to meet Campbell, and forms an apparently sound defensive position bordered on both flanks by swampland. But a local slave shows Campbell a path through the swamp on Howe’s right flank and he swings some 600 men into Howe’s rear. Once the first shots are fired, the surprise sends the Americans fleeing in every direction, with thirty or more drowning in the swamp. Nearly 100 Patriots are killed or wounded on December 29 and another 453 are captured. Campbell suffers only 24 casualties. Robert Howe is subsequently court-marshalled for his actions, but eventually exonerated.

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1778

| 1778 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Feb 6 | Treaty of Alliance | — | Patriots | — | France recognizes and aligns with U.S. |

| June 28 | Monmouth | NJ | Draw | 1600 | British withdraw to New York |

| Dec 29 | 1st Savannah | Ga | British | 600 | A major win for General Clinton |

As 1779 opens, Britain’s “southern strategy” calls for consolidating the victory at Savannah, recruiting Loyalists to enhance their manpower, and moving up the coast into South Carolina toward the critical harbor at Charleston.

The opening task is handed to Major William Gardner and 200 infantrymen who head out on longboats toward the town of Beaufort, 40 miles above Savannah. Overlooking Beaufort is Port Royal Island, home to tiny Ft. Lyttleton and a few Continentals under Captain John DeTreville. Gardner’s men land there on January 29 to find that DeTreville has spiked the cannons and blown up the fort.

The fight then shifts to the mainland around Beaufort, where DeTreville has been joined by another small militia unit under General William Moultrie. Among them are two signers of the Declaration of Independence (Edward Rutledge and Thomas Heywood, Jr.) and several black volunteers. On February 3, Moultrie takes the high ground at Gray’s Hill Plantation and fires into Gardner’s 60th Foot Regulars who advance with fixed bayonets. The battle wavers for 45 minutes before Gardner orders a retreat. Some 20 redcoats are captured and another 40 are killed or wounded. The American lose 30 men while gaining a morale boosting victory.

In late April, General Ben Lincoln, who succeeds Benedict Arnold after Saratoga, orders Moultrie with 1200 troops to stay between General Prevost’s redcoat army and Charleston. Lincoln himself then heads with 4000 men to Augusta, Georgia, intent on recapturing Savannah.

An Initial British Attempt At Charleston Is Abandoned

General Prevost decides to ignore Lincoln and try to capture Charleston. As Prevost approaches, Moultrie falls back to the city to organize his defenses. Prevost’s 3000 man army moves southeast across the Ashley River on May 11 and overruns “Pulaski’s Legion,” a small 60 man Patriot unit under Polish leader Casimir Pulaski who tries to slow the attack.

Inside Charleston, the Privy Council is convinced the city will fall, while General Moultrie is equally convinced that he can hold on. On May 12 the Council sends a message to Prevost offering to declare Charleston an “open (neutral) city” in exchange for not bombarding it. This despite Moultrie’s declaration to fight on. Then comes a shock when May 13 opens with Prevost’s army having withdrawn overnight. The impetus is the approach of General Lincoln’s army which has backtracked from Savannah to defend Charleston. Thus the city remains for now in Patriot hands.

After the fact, General Lincoln is roundly criticized for initially ignoring Charleston, and he offers his resignation. But it is denied and he remains in Charleston while plotting his next move against Savannah.

A Joint Patriot-French Effort Fails To Re-take Savannah

Lincoln is now convinced that his forces alone are insufficient for the task, and turns to the Frenchman Admiral Charles D’Estaing for assistance. Over the summer of 1779, D’Estaing has been challenging the Royal Navy in the West Indies, but he agrees to swing north with 25 ships and 3,500 troops and support Lincoln at Savannah.

On September 12, d’Estaing, in overall command, debarks at Beaulieu’s Plantation and entrenches south of the city. Four days later, Lincoln joins him with 1500 Continentals and militia. After a message calling for General Prevost to surrender is rejected, the siege begins.

But if fails to dislodge the redcoats, and D’Estaing, fearing for his ships and supplies, calls for a frontal assault on October 9. It too flounders, with D’Estaing wounded twice in the action and General Pulaski killed. Total losses are 830 soldiers for the allies against only 103 for the British. Lincoln pleads with D’Estaing to try again, but the siege ends on October 17. (D’Estaing lives on until 1794 when he is guillotined during the Reign of Terror.)

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1779

| 1779 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Feb 3 | Beaufort | SC | Patriots | 90 | Morale boost for Patriots |

| May 11-12 | Charleston raid | SC | Patriots | ?? | Prevost approaches then departs |

| Sept 19-Oct 17 | 2nd Savannah | Ga | British | 930 | Patriot-French alliance fails |

General Henry Clinton, Commander-in-Chief of all British troops in America is delighted by the defense of Savannah and now commits to trying for a third time to conquer Charleston. He concludes that General Prevost’s attempt in May 1779 failed for a lack of enough firepower. So this time he will go all in. On December 26, 1779 he assigns the defense of New York to Prussian General von Knyphausen and his 15,000 troops, and sets sail himself with 8500 men and 14 warships toward Charleston.

Charleston Falls To Redcoat General Clinton In 1780

Winter storms in the Atlantic make the voyage chaotic, and Clinton doesn’t land until February 11, 1780, at the Edisto Inlet, 40 miles southwest of his target. On March 6 he seizes Ft. Johnson east of the city, then crosses the Ashley River on March 29 and lays out his siege lines. On April 8 he is joined by seven British frigates that enter the harbor adjacent to the central city.

Like Manhattan, Charleston is on the apex of a peninsula surrounded on both sides by water, and hence very vulnerable to encirclement. Inside Founding Father John Rutledge uses his power as South Carolina Governor to impress residents, including some 600 slaves, to fortify the city. Beyond that, his fate is in the hands of General Lincoln’s 5,500 troops.

Clinton launches his opening attack on April 13. The next day the soon notorious Colonel Banastre Tarlton closes off the final potential breakout route north from the city. The Colonel commands “Tarleton’s Raiders,” made up of the local Loyalists, exactly the men that Britain was counting on to rally to their side in the South. By May 8, Clinton has opened the harbor to his warships and prepares for a frontal assault. He asks Lincoln to surrender but the American stalls, and the next day the two sides exchange fire. With morale inside broken, the Privy Council pleads with Lincoln to give up, and he complies on May 12. The surrender of his 5,500 troops becomes the third largest capitulation in American history.

Clinton now holds both Savannah and Charleston and has eliminated the main Continental army in the South. This becomes the chance for Britain to carry the war across Georgia and the Carolinas with its Regulars and the hoped-for Loyalists to the Crown. To encourage new recruits, Clinton announces that any locals who participate in supporting King George will be forgiven for all prior violations once the war is won.

Clinton feels that he has accomplished his objectives in the south and must return to New York to contend with Washington’s main body in the north. He leaves a modest 3500 troops in place under the command of Lord Cornwallis who has been at his side off and on since 1776.

The Inland Battles For Georgia And The Carolinas Get Under Way

Cornwallis begins by establishing a string of outposts designed to operate across the interior of South Carolina in particular. He assigns the fiery Colonel Tarleton to maraud across the countryside and lead local Loyalists against their neighbor Secessionists.

For the next two and a half years, the Revolutionary War will be fought across the South. Opposing Cornwallis early on is General Horatio Gates, falsely credited with the victory at Saratoga that rightly belonged to Benedict Arnold. Gates is sent to restore Patriot morale, but will prove a failure.

On May 20 a particularly vicious battle occurs at Waxhaws, adjacent to the North Carolina border. There roughly 150 dragoons under Tarleton catch up with the rear guard of Colonel Abraham Buford’s 400 man brigade marching toward Charlotte. Tarleton contacts Buford under a white flag, claims a much larger force than he has, demands a surrender, while all the time laying a trap up ahead. Buford refuses to surrender and resumes his march before being surprised and overwhelmed by the redcoat cavalry. After Tarleton is wounded, his troops take their revenge on the American troops, slaughtering many who had dropped their weapons.

Buford’s casualties number 113 killed, 150 wounded and 53 captured, although Buford himself escapes. Tarleton suffers only 17 casualties, while again earning his “No Quarters” reputation.

August 16, 1780 brings another defeat for Gates and the Patriots, this time at the Battle of Camden, South Carolina. Gates’ men are starving at the time and his target is a British supply train said to be located around Camden. He heads there with his roughly 4,000 Regulars and militia. Cornwallis learns of the advance and moves out to meet Gates with half as many men. The two armies blunder into each other five miles north of Camden on the night of August 15. Despite his 2:1 manpower edge, Gates misaligns his brigades. He puts all of his Continents in the traditional “place of honor” on his right flank and almost all of his inexperienced militia on his left. The clever tactician, Cornwallis, sees this and easily breaks through. Instead of rallying his soldiers, Gates flees the field once the left-side rout begins, riding away toward Charlotte. An envelopment movement by Cornwallis follows, with the capture of roughly 1,000 Patriots, added to another 800 killed or wounded. The redcoat casualties are 300 on the day. The defeat humiliates Gates and ends his military career.

A confident Cornwallis now tries to consolidate his gains in South Carolina by putting an end to Patriot raids on his outposts across the state. He calls upon Major Patrick Ferguson to lead the campaign. Ferguson is a rising star for Britain and has successfully recruited his own legion of some 1,200 Loyalists. On October 7, 1780, he is leading them toward Charlotte, North Carolina, while being harassed by a 1,000 man band of American frontiersmen under the command of Colonels John Sevier and William Campbell, the latter known as a “bloody tyrant” among the Loyalists. Around 10:00am, Ferguson decides to turn and attack the Patriots at King’s Mountain, South Carolina.

The battle site is surrounded on all sides by thick forests with King’s Mountain running a mile long from its highest elevation of 1060 feet down to a lower plateau. Sevier and Campbell hold the high ground and utilize Indian-style tactics to pick off the redcoats who respond with several traditional bayonet charges. But then a mounted Patrick Ferguson is struck my multiple musket balls and falls dead near the foot of the hill. This panics his Loyalists and some 600 of them are captured on the spot. In revenge for Tarleton’s murderous behavior at Waxhaws, some who surrender are shot down while other will eventually be hanged as traitors. The Americans suffer 90 total casualties, while the Loyalist lose over 1100, almost their entire army.

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1780

| 1780 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Mar 29-May 12 | Charleston | SC | British | 5,900 | General Lincoln loses his entire army |

| May 20 | Waxhaws | Sc | British | 330 | Tarleton’s raiders/massacre |

| Aug 16 | Camden | SC | British | 2100 | Gates disastrous loss ends his career |

| Oct 7 | Kings Mountain | SC | Patriots | 1200 | Frontiersmen trounce Loyalists |

Washington chooses General Nathanael Greene to replace the discredited Horatio Gates, and he arrives in December 1780 to take command. He inherits only 1500 men fit for duty, and is forced to divide them in two to cover the vast South Carolina frontier.

Some 600 go to Daniel Morgan who has a sterling combat record from Quebec to Manhattan and Saratoga, but is repeatedly passed over for promotions which go to others more politically connected. He retires temporarily until Gates’ disaster at Camden brings him back and finally as a Brigadier General. His assignment is to move west from the Patriot HQ at Charlotte to further press the British Loyalists. General Greene takes the remaining 900 troops south to corral needed supplies at Cheraw, South Carolina.

Cornwallis’ Southern Campaign Flames Out

Meanwhile the sobering loss at King’s Mountain dampens Cornwallis’ hope to expand into North Carolina. Instead he sends Benastre Tarlton to get in between the two Patriot army wings and defeat each in detail. January 6, 1781 finds Tarleton starting after Morgan who decides to fight near a campsite known as Cowpens, 35 miles west of King’s Mountain. On January 17, Morgan executes a clever plan using retreating militia to draw the redcoats into an ambush against his well-trained Continentals. British casualties total 340 killed or wounded and another 525 captured. Morgan suffers 150 casualties while putting a final end to Tarleton’s reputation for invincibility.

After the Cowpen’s victory, Morgan races into North Carolina and hooks up with Greene’s troops in early March. Cornwallis chases after and catches them on March 15 at Guilford Court House, 90 miles northeast of Charlotte. Morgan is forced to retire after falling ill, but Greene attempts to repeat his previously successful ambush plan. But after inflicting some 500 casualties on Cornwallis, as opposed to 260 of his own, Greene decides to leave the field in British hands. He then loops back south, deploying at Hobkirk’s Hill, South Carolina, 3 miles south of Camden.

The Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25, 1781, ends indecisively, but it signals closure on the British campaign to win Georgia and the Carolinas. After 18 months, all Cornwallis has to show for his efforts are the ports at Savannah and Charleston he won early on.

June 6 marks another Patriot win, this time at Augusta, Georgia where General Andrew Pickens and Colonel “Light Horse Harry” Lee (father of Robert E) complete a two week siege of the city.

The last clash in the south comes on September 8, 1781 at Eutaw Springs, 75 miles south of Camden on the way to the ocean. It is a fierce battle between General Greene’s 2400 troops and some 2000 redcoats under Lt. Colonel Alexander Stewart. Casualties are steep on both sides, the Patriots losing 550 men and the British almost 700.

The World Turned Upside Down At Yorktown, Virginia

Between Hobkirk’s Hill and Eutaw Springs, the Revolutionary War’s endgame is taking shape in Virginia. Over the winter of 1781, British forces, often led by Benedict Arnold, have marauded across the state, occupying the capital of Richmond in January. This incursion into his home state alarms Washington and he sends 5,000 troops under command of the French General Marquis de Lafayette, to defend Virginia and capture the traitor, Arnold.

Given that Cornwallis has 7,000 troops at his disposal, Lafayette decides to avoid a major battle, instead maneuvering his army along the Rapidan River toward Williamsburg. A sharp skirmish is fought there on July 6, 1781.

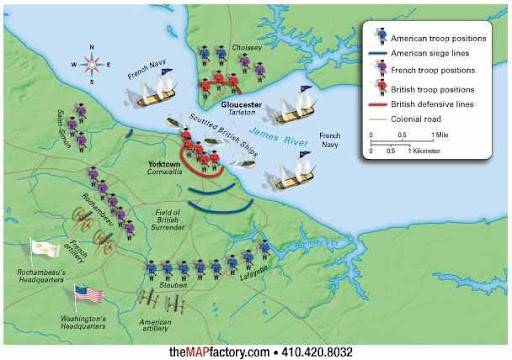

At this point, General Clinton, resting comfortably in Manhattan, senses that the combined 9,000 man force of Washington and the Frenchman, Rochambeau, may be readying a move against him up north. In response he first orders Cornwallis to detach 3,000 men back to NYC, then changes his mind and tells him to occupy the deep water port at Yorktown, which he does.

At first, this move to Yorktown looks safe – but then two crucial factors shift the equation.

On May 22, Washington learns that French Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, plans to move his fleet from the Caribbean to America in the Fall, to support the alliance. For the first time in the war, Britain’s absolute dominance of all sea lanes will be challenged.

Then Washington settles on a major gamble, reminiscent of his desperate move across the Delaware to Trenton some five years earlier. He leaves a shadow army of 3,000 to contain Clinton in New York, and secretly marches with Rochambeau and 6,000 men on August 21 to join Lafayette. Fortunately Clinton does not learn of the move until September 2, when Washington’s army meets Admiral De Grasse’s fleet in Chesapeake Bay, north of Baltimore.

In addition to his navy, the Admiral brings another pleasant surprise – 2,500 French troops, who disembark to bolster the American-French infantry. Suddenly a joint land and sea attack on Cornwallis at Yorktown becomes possible.

After settling on a plan, Washington and Rochambeau move overland for 12 days to join up with LaFayette in Williamsburg on September 14.

In the interim, Admiral De Grasse fights a crucial sea battle with British Admirals, Sir Thomas Graves and Sir Samuel Hood, that will seal the fate for Cornwallis at Yorktown.

When DeGrasse moves north from Haiti on August 15, Graves and Hood follow him, but with only a part of the fleet, leaving the rest behind to defend the West Indies. This decision proves fateful on September 5 in the Battle of the Capes, fought for control of the entrance to James River and the Yorktown harbor.

In the early afternoon De Grasse brings his 24 warships out past Cape Henry, heading southeast and signaling the classical order “form line of battle.” The awaiting British fleet of 19 ships tacks with him, foregoes a thrust at his center, and instead opts for a broadside exchange of fire. But Hood’s rear guard never quite catches up to the French, and only eight of the Royal Navy actually close within range of DeGrasse’s main body of fifteen. This nearly 2:1 advantage in firepower pays off in a French victory, after two hours of intense fighting.

The two fleets continue to maneuver out of range off the Capes until September 10 when DeGrasse moves back into the shelter of Chesapeake Bay. There he is greeted by another French squadron under Admiral de Barras, which brings his strength up to 35 ships, guaranteeing control of the waters surrounding Yorktown.

At this point, Cornwallis’s 7200 man army is trapped – between the French fleet on the York River and Washington’s predominantly French force of 16,500 infantry who have surrounded him by September 28 from the east and south.

When Clinton sends word promising a relief force from New York, Cornwallis abandons his outer defenses and pulls back to a more tightly controlled perimeter. In turn, Washington and Lafayette are able to construct close-in siege operations, with cannon fire taking its daily toll on the British defenders. By October 10, Cornwallis signals Clinton that his only remaining hope is a rescue by the Royal Navy. Four days later, two critical redoubts (#9 and #10) are stormed, closing the gap between the British and their assailants to only 250 yards.

The end comes on the morning of October 19, 1781, to the beat of the long roll followed by a white flag of surrender from Cornwallis. Formal papers are signed and in the early afternoon the British army marches out of their fortifications to surrender, accompanied appropriately by a popular London tune, “The World Turned Upside Down.”

Key Revolutionary War Battles: 1781

| 1781 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Jan 17 | Cowpens | SC | Patriots | 1000 | Ends Tarlton’s reputation as invincable |

| Mar 15 | Guilford Court Hse | NC | Draw | 750 | But heavy British losses |

| April 25 | Hobkirks Hill | SC | Draw | 1250 | Cornwallis troops wearing out |

| May 22-June 8 | Augusta | Ga | Patriots | 430 | Patriot momentum continues |

| July 21 | Louisbourg | Nova S | French | 100 | Small naval skirmish won by France |

| Sept 5 | Chesapeake Capes | Va | French | 560 | Crucial win for French and Patriots |

| Sept 8 | Eutaw Springs | SC | Draw | 1250 | Final clash in the southern theater |

| Sept 28-Oct 19 | Yorktown | Va | Fr + Pat | 1050 | The world turned upside down |

The success of the American-French alliance at Yorktown effectively signals the end of British rule over the thirteen colonies – although it takes almost two more years of sporadic warfare to drive the point home in London.

King George is willing to continue the fight, but his Parliament is not. The wartime Prime Minister, Lord North, is forced out in March of 1782.

In the spring, Ben Franklin opens unilateral talks with British counterparts, fearing that the French commitment to an ongoing alliance may be softening. He is joined over time by two other American diplomats, John Adams and John Jay.

By November 1782 a draft treaty is signed, with the opening declaration reading:

His Britannic Majesty acknowledges the said United States…to be free, sovereign and independent.

Still another ten months pass before a final agreement is concluded in Paris on September 3, 1783.

Franklin wants Britain to cede eastern Canada to reduce the odds of a future invasion, but the crown balks at the idea. Instead, the British transfer the land west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi River, to the dismay of their tribal allies.

Other articles grant fishing rights to the United States in Canadian waters and access by Britain to the Mississippi River; finalize payment of outstanding debts; arrange for exchange of prisoners; and protect the rights of any residual Loyalists.

The Treaty of Paris ends the first war between mostly British brethren in America.

The victory of the upstart rebels is an improbable one, and much of the credit falls to one man, General George Washington, whose leadership and sheer determination span over six years of often desperate warfare.

Before long the new nation he secured will ask him to forego private life for another call of duty, this time in the political arena.