Section #6 - “Bloody Kansas”

“Bloody Kansas:” 1854-59

Early History Of Slavery In The United States

While slavery exists in all thirteen British colonies, by the time of the 1787 Constitutional Convention its economic importance is fading away in the north while becoming more vital in the south. Debates in Philadelphia over whether or not it should continue over time almost derail the effort to form a union. But in the end a series of compromises are worked out.

Among them is the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 which establishes the territorial boundaries separating Slave States from Free States. The geographic demarcation starts with the Mason-Dixon Line in the east and runs westward along the Ohio River all the way to its junction with the Mississippi River in southern Illinois.

This precedent solves the issue until 1819 when the Missouri Territory applies for admission to the Union. It is located in the Louisiana Purchase land acquired from France in 1803 and is therefore not covered by the Northwest Ordinance.

The fact that it is situated adjacent to the Free State of Illinois, with 90% of its landmass north of the Ohio River terminal at Cairo, implies a “Free State” designation. But slavery is already well entrenched in Missouri and the settlers there are ready to fight to avoid a ban.

The issues is further complicated in February 1819 when a New York Congressman, James Tallmadge, offers an amendment stating that Missouri should be admitted only if…

The further introduction of slavery or involuntary servitude be prohibited, except for

the punishment of crimes… and that all children born within the said State, after the

admission thereof into the Union, shall be free at the age of twenty-five years

Southern representative vote 66-1 against passage, only to be overwhelmed by Northerners who vote 88-10 in favor. Upon hearing this outcome, Thomas Jefferson calls the Tallmadge Amendment “a fire bell in the night” sure to re-open the sharp divisions over slavery that threatened the union in 1787.

On top of that, political leverage in the Senate is at stake in the decision which in 1819 is evenly divided between 12 Free and 12 Slave States.

Threats of violence and secession ring out across the capital before Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, offers up what becomes known as the Missouri Compromise with its three central provisions:

- The admission of Missouri as a Slave State;

- The simultaneous admission of Maine as a Free State to achieve a 13:13 Senate; and

- The creation of a 36’30” line extending west from the lower boundary of Missouri across the Louisiana parcel with future Free States to the north and Slave States to the south.

This defuses the immediate conflict over Missouri and provides a clear demarcation line for any future admissions within the Louisiana territory. It does not solve the many ongoing North-South conflicts related to slavery, but it does provide enough glue to hold the union together.

Then Comes The Mexican War

Along with the 1844 election of James Knox Polk comes growing public support for “Manifest Destiny,” the notion that America’s borders should extend all the way to the pacific coast. Polk advocates for this and, as another southern slave-holder, sees it as a way to open new cotton plantations across the west. He moves in that direction by annexing Texas as he enters office, and then sends American troops to the Mexican border, ostensibly to defend U.S. territory.

When the Mexicans object, a 17 month war breaks out which ends in 1847 with a decisive American victory and the forced cession of 529,000 square miles of land in the 1848 Treaty

of Hidalgo.

While President Polk and the Democrats praise this outcome, it is harshly criticized by opponents, among them Congressman Abraham Lincoln and Senator Henry Clay. Together

they label the war naked aggression by a stronger state against a weaker one. And three

decades after the fact, one of the participants, Ulysses S. Grant, brevetted to Captain

for bravery with the 4th U.S. Infantry, seconds their observations:

I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States

on Mexico. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral

courage enough to resign.

Not only do opponents condemn the war, they also accuse Polk of lying about the claim that Mexico initiated it, and argue that his intent all along was to extend the “slavocracy” into the western lands.

Efforts to ban this extension surface throughout the course of the war, most notably in August 1846 when David Wilmot, a first-year congressman from Pennsylvania announces that he will support a funding expenditure, but only:

Provided that, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any

territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty

…negotiated between them… neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever

exist in any part of said territory.

When Wilmot’s Proviso passes in the House along sectional, not party lines, it becomes a stake in the ground announcing Northern opposition to slavery in the west.

Southerners are outraged by the proposed ban. They argue that their blood was spilt in the war to secure the new land and they deserve to share in the spoils. Furthermore they claim that the federal government has no right to interfere in the practice of slavery, and that the ban will ruin the Southern economy by limiting sales of its human assets in the west.

This latter assertion is borne out by economic data in 1860 showing that the “market value” of the South’s 3.9 million slaves far exceeds that of its cotton crop and approaches that of the entire GDP of the nation.

Economic Statistics In 1860

| Market Value | |

| 3.9 million Southern slaves | $3.0 Billion |

| The South’s cotton crop | 1.2 Billion |

| All U.S. railroads | 1.2 Billion |

| Total U.S. GDP | 4.4 Billion |

To maximize future wealth, the South depends on selling its “excess bred slaves” in the east to new start-up plantations in the west.

Congress Searches For Another Compromise On Slavery

The acreage gained from Mexico will end up representing roughly 18% of America’s total landmass, and eventually comprises 9 states: all of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Which compares to the 30 states existing in 1848, with 15 Free and 15 Slave.

So the politicians in Washington are well aware of the stakes involved in deciding whether slavery will be permitted and, if so, where.

The burden for a resolution falls heavily on the shoulders of the Democrats and two leaders who will follow Polk: the 68 year old Michigan Senator, Lewis Cass, and the party up-and-comer, 37 year old Stephen Douglas. Both are intent on reaching a solution in order to open commerce and railroading in the Mississippi Valley. Both are dependent on Southern support to achieve their personal ambitions to be president. As a hidden slave-holder, Douglas also has a financial interest in extending slavery to the west.

But even though the Democrat Party enjoys solid majorities in both chambers of Congress, the fact is that, in the House, the Free States have 143 seats to only 90 for the Slave States. Thus, if the North bands together over a slavery decision across party lines, it can swamp any demands from the South. Just as it has continued to do by favoring the Wilmot Proviso.

To escape the potential for a ban on slavery in the new territories, Cass and Douglas come up with an option they call “popular sovereignty.” Rather than a federal decision, they say, wouldn’t a fairer alternative lie in letting the settlers in each territory vote on whether they want to be declared a Free or a Slave State? Isn’t that consistent with the essence of democracy?

The tenacious Douglas pushes this popular sovereignty answer through Congress as part of the 1850 Compromise and the newly elected President Franklin Pierce supports it in his role as a “doughface” – a northern born man whose loyalties reside with the south.

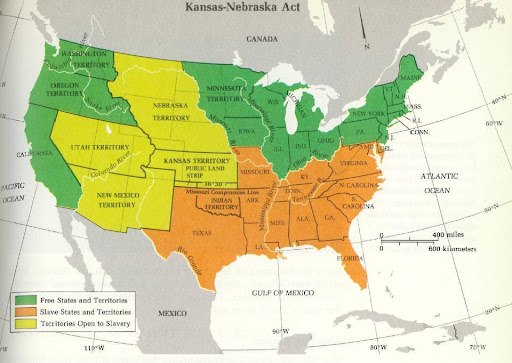

Then, in 1854, Douglas drives the highly controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act into law. The Act sets the stage to admit the Kansas and Nebraska Territories to the Union. Both lie north of the 36’30” demarcation line agreed to in the 1820 Missouri Compromise which would make them Free States. But Douglas declares that that line is no longer in effect and has been replaced by his “popular sovereignty option. This reneging on the 36’30” precedent prompts the founding of the Republican Party and brings Abraham Lincoln back into politics. It also turns all eyes to Kansas as a test of Douglas’ “solution.”

The Battle Over Slavery In Kansas Begins

Starting in 1854 a violent five year conflict breaks out in the Kansas Territory that becomes a rehearsal for the Civil War. It involves the central issue that divides the North and South: whether or not slavery will be allowed in the state.

President Pierce is well aware of the national focus on Kansas and he appoints Andrew Reeder as the first of what will become six different territorial Governors. On the face of it, Reeder seems like a safe choice for the job. He is a loyal Democrat from Pennsylvania and one, like Pierce, who is sympathetic toward the South and a vigorous advocate of popular sovereignty. He is also an aggressive land speculator, having acquired some 1200 acres along the Kansas River at 90 cents apiece.

The Governor’s first job is to establish voting districts and hold a fair election to choose a territorial delegate to represent Kansas in Washington. Three candidates vie for the honor, one pro-slavery man, J.W. Whitfield, and two others who are anti-slavery.

But when the election is held on November 29, 1854, Slave State supporters from Missouri – led by U.S. Senator David Atchison and militia General, Benjamin Stringfellow – flock across the river into Kansas and stuff the ballot boxes for Whitfield. Governor Reeder recognizes that the 79% — 21% vote is fraudulent, but approves it to avoid controversy.

Next comes the vote to elect a Kansas legislature and, on March 30, 1855, the same “Missouri Ruffians” return to take over the polling places and record 5,427 ballots for the pro-slavery slate, roughly 2,500 more than the total residents eligible to participate.

This time Reeder balks at the outcome and travels to Washington to meet with President Pierce and gain approval to prevent the “Bogus Legislature” from acting. But this doesn’t happen, and on July 2, 1855, the Pro-Slavery legislators gather in the frontier town of Pawnee, with banners signaling their aims:

Kansas for the South, now and forever; Negro Slavery For Kansas;

Hemp For Negro-Stealers; The South And Her Institutions.

They officially declare Kansas a Slave State, and pass a law stating that the publication or circulation of all anti-slavery material will be punishable by two years of hard labor.

When Reeder vetoes some of their acts, he is assaulted in his office and threatened with death. After one attack he writes to his wife saying that she may never see him again.

In July 1855 the Kansas settlers who favor Free State status begin to organize behind the leadership of Charles Robinson, a Massachusetts native and son of an abolitionist, who has travelled to California during the gold rush and serves in the state legislature there. As a member of the “New England Immigrant Aid Company” he announces his position in a 4th of July speech in the town of Lawrence:

The doctrine of self-government is to be trampled underfoot here…the question of negro

slavery is to sink into insignificance, and the greater portentous issue is to loom up in its

stead, whether or not we shall be the slaves, and fanatics who disgrace the honorable and

chivalric men of the south shall be our masters to rule at their pleasure.

Robinson’s message resonates with his Lawrence audience, and they agree to convene a follow-up meeting to plan their strategy. This takes place on August 14-15 where agreement is reached to elect their own state legislature and write a Free State Constitution.

In the interim, complaints about Andrew Reeder’s actions as Territorial Governor of Kansas descend on Pierce from Atchison and the Pro-Slavery legislature, meeting in Lecompton. The President finally gives in to the pressure and demands that Reeder resign, effective August 15.

Upon hearing the news, Reeder’s response proves surprising. Instead of fleeing from the territory in disgrace, he chooses to sign on with the “Free State Party,” joins their first convention, and becomes a leader in their battle against the Pro-Slavers.

On September 5, 1855, roughly one hundred Free State delegates, along with other spectators, gather at Big Springs, 15 miles west of Lawrence on the old California Trail. Charles Robinson is there, along with now ex-Governor Reeder, and a new voice in the mix, one James Henry Lane, an Indiana native who serves in the Mexican War and then in the U.S. House before coming to Kansas to establish a Democratic Party.

Lane’s men arrive at the Big Springs Convention armed with Sharps Rifles and ready for combat. They share none of Robinson’s moral opposition to slavery; instead they are simply dedicated to keeping all blacks out of Kansas.

In spite of these fundamentally different motivations, a Free State Party is born at the convention. It is dedicated to forming a government chosen by actual residents of Kansas and not Missouri. Instead of merely opposing the Slave State Party, it takes the bold step of electing its own legislature from those present, and then chooses none other than Andrew Reeder as it proposed representative to the U.S. House.

The ex-Governor’s closing resolution is ominous. It calls upon supporters to procure arms, train up volunteer companies, and prepare for a bloody resistance should peaceful remedies fail.

That we will endure and submit to these laws (the bogus laws) no longer than the best interests of the Territory required, as the least of two evils, and will resist them to a bloody issue as soon as we ascertain that peaceful remedies shall fail, and forcible resistance shall furnish any reasonable prospect of success; and that in the meantime we recommend to our friends throughout the Territory the organization and discipline of volunteer companies, and the procurement and preparation of arms.

When word of the Free Stater’s plans become known, the pro-slavery forces set up a series of “associations” of their own. One is the “Order of the Knights of the Golden Circle” comprising those who hope to open new slave territory in Mexico, Central America and Cuba, in addition to the American west. Others include the “Golden Circle,” the “Friends of the South,” the “Social Band” and the “Dark Lantern Society.” All meetings are held in secret and mirror the kinds of practices and rituals familiar to the Freemasons.

The Missouri branch is known as the “Platte County Self-Defense Association.” Its Secretary is Benjamin F. Stringfellow and its “blue lodges” spring up across Kansas.

Pierce again signals his support for the Slave State coalition, naming ex-Ohio Governor, Wilson Shannon, to replace Reeder. He is another “doughface” politician, who has recently completed a term in the U.S House. Sworn in on September 7, 1855, he will be gone in eleven months, after failing to stifle the Free State movement.

On September 19, thirty-seven Free State delegates reconvene in Topeka to draft their constitution. They are predominantly Northerners by birth and Democrats by political affiliation. Most are farmers or lawyers, and under forty years of age.

The convention lasts for sixteen straight days and proves highly contentious.

In many ways it is a microcosm of the conflicting views regarding slavery, and blacks in general, that prevails in the North and West. On one hand, there are those like Robinson who are morally opposed to slavery; on the other, the blatantly racist Lane men who want to secure Kansas for white men only by excluding all blacks from residing in its borders.

One contentious issue right away focuses on whether to support reinstatement of the 36’30” boundary line settled in the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Despite the fact that this would assure Kansas of Free State status, a motion is narrowly defeated by a 15-17 margin, a reflection of the number of loyal “pop sov” Democrats and Southerners who are present.

A second proposal originates with the “Lane faction,” calling for a flat-out ban on all blacks – slave or free – from entering or residing within the borders of the new state.

The true Abolitionists at the convention are appalled by the notion that Free Blacks would be denied entrance into Kansas. Lane’s anti-black racists are likewise appalled by the prospect of any Africans living in their midst. Between the two extremes are the moderates, not on a crusade, but simply wanting to contain the problems with slavery where they belong, in the South.

After much back and forth, a compromise is reached whereby the “Black Exclusion Clause” will be kept separate from the main body of the Constitution, but will still be voted on at a future general election.

When all done, the final Topeka Constitution is an elaborate affair, mirroring prior frameworks, including a familiarly crafted Preamble:

We, the people of the Territory of Kansas, by our delegates in Convention assembled at Topeka..having the right of admission into the Union as one of the United States of America, consistent with the Federal Constitution, and by virtue of the treaty of cession by France to the United States of the Province of Louisiana, in order to secure to ourselves and our posterity the enjoyment of all the rights of life, liberty and property, and the free pursuit of happiness, do mutually agree with each other to form ourselves into a free and independent State, by the name and style of the State of Kansas….

It is followed by twenty-seven separate Articles covering the gamut from a Bill of Rights to the structure and duties of the proposed branches of government, electoral procedures (with a six month residency requirement), provisions for public institutions, taxing and finances, and so forth.

The subject of slavery is addressed in Article 1. Section 6 declares that Kansas will be a Free State.

Sec. 6. There shall be no slavery in this state, nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crime.

Section 21 prohibits owners from bringing their slaves into the state under the guise of renaming them “indentured servants.”

Sec. 21. No indenture of any negro or mulatto, made and executed out of the bounds of the State, shall be valid within the State.

With their Constitution now written, the Free State Party calls for ratification vote on December 15, 1855.

The Initial Shedding Of Blood In The Territory

In parallel with their efforts to form their “legitimate government,” the Free Staters also ready themselves to go to war with the Missouri men if need be.

Their preparations begin early in 1855 with the formation of the “Kansas Legion,” another secret order with members who wear black ribbons and define their mission as:

First, to secure to Kansas the blessing and prosperity of being a Free State; and secondly, to protect the ballot box from the leprous touch of unprincipled men.

Securing the armaments needed for potential combat is a priority for the Free State men, and they send James Abbott, an early New England Emigrant Aid Society transplant, back east for help. Ironically two abolitionist preachers, Henry Ward Beecher and Thomas Higginson, respond with a shipment of 117 Sharp’s rifles, crated up in boxes, marked “Bibles,” and sent west – along with one 12 lb. howitzer, canister and fused shells. The eastern press hears of this move and christens the cargo “Beecher’s Bibles.”

At the same time, the Pro-Slavery forces prepare for battle. On October 3, 1855, they organize a “Law and Order” posse dedicated to putting down “treason” in Kansas. In mid-November they meet in Leavenworth, with Governor Shannon present, to plot their strategies.

Both sides are now prepared to win through violence, and it begins on November 21, when one Charles Dow is murdered by Franklin Coleman at Hickory Point, near the town of Wakarusa. This act sets off what becomes known as the “Wakarusa War.”

While Dow is a Free Stater and Coleman a Missouri man, the motive for murder is not about slavery, but rather a heated dispute between the two neighbors over ownership of a 250 yard strip of land adjacent to their homes. The quarrel leaves Dow bleeding to death in town from a shotgun wound, while Coleman retreats to his home to await arrest for his act.

Dow’s friend, Jacob Branson, collects his body and has it buried. He then organizes a Free State “committee of vigilance” meeting on November 26 to decide how to avenge the death. A posse is formed to capture Coleman. It ends up burning down his house after learning he has fled.

This act leads to Branson’s arrest by Sheriff Samuel Jones for “disturbing the peace.” But on the way to jail, a band of Branson’s Free State friends threaten violence to gain his release. Sheriff Jones responds with restraint by surrendering Branson, who returns to Lawrence and the safety of Charles Robinson’s home.

From there, tensions mount quickly. Jones informs Governor Shannon of Branson’s abduction. Shannon responds by calling out the territorial militia and issuing a public plea for help to restore law and order. The public response is more than the Governor bargains for, as roughly 1500 Pro-Slavery Missourians show up, all eager to attack the town of Lawrence and kill Branson along with his backers.

The Missouri raiders assemble their main camp below the Wakarusa River, running west to east, just south of Lawrence, and prepare for a siege by establishing blockades along all roads into town. Free State defenders inside Lawrence prepare a series of circular earthen forts, some seven feet high and one hundred feet across, along with connecting trenches and other rifle pits. They are commanded by James Henry Lane, who begins to earn his lasting nickname as “The Grim Chieftan.”

As the siege begins, so too do negotiations involving Governor Shannon and the two sides.

Violence is avoided until the afternoon of December 6, when three perhaps unwitting Free State riders are stopped on a road leading to their homes, and interrogated as to their intentions. After guns are drawn, two men escape, but a third, named Thomas Barber, is killed by the Missourians.

Word of Barber’s death reaches Governor Shannon, who now fears that his militia units will be unable to stem a full out assault on Lawrence by the Pro-Slavery troops.

To forestall more bloodshed, Shannon again meets both sides to work out a peaceful settlement. On December 8, 1856 he enjoys a moment of success when an agreement is signed by ex-Senator David Atchison, Charles Robinson and James Lane. Its content is relatively anodyne: in exchange for no longer harboring Jacob Branson from prosecution (even though he has already left town), the government will lift the siege and not hold the citizens of Lawrence in contempt of the law.

For those in Lawrence, the outcome is regarded as a victory – and a gala ball is held to celebrate. Their city is intact; the Pro-Slavery forces have backed away; and the slain Thomas Barber will not have died in vain. To insure their future protection, Governor Shannon, perhaps inebriated at the time, also officially authorizes the Free Staters to form their own protective militia, something he will later regret.

The response to the Branson affair among the Border Ruffians is anger. Not only have they been deprived of the military victory they prepared for at Lawrence, but both Jacob Branson and the Free State “nullifiers” have escaped without punishment. David Atchison, who signed the accord, defends his action by saying that a slaughter would have built sympathy in the North for a Free Kansas, and forced Washington to take a closer look at the legitimacy of the Pro-Slavery election wins.

One figure who misses out on this action in Lawrence is the fiery abolitionist, John Brown, who moves to Kansas a year earlier to join three of his sons in fighting on behalf of the Free Staters. Brown settles at the town of Pottawatomie Creek, some 50 miles south of Lawrence. When he learns of the pending siege, he heads toward the conflict, only to arrive after the truce is negotiated.

Following the anti-climactic “Wakarusa War,” the time arrives for the Free State Party to submit its Topeka Constitution to a vote, in line with their interpretation of the popular sovereignty procedures. Polling takes place on December 15, 1855, and this time it is largely peaceful as the Pro-Slavery Missouri men simply choose to ignore the event as irrelevant.

Two documents are voted on – first the Topeka Constitution itself, and second the “Black Exclusion” measure. The Constitution is approved almost unanimously.

Topeka Constitution Voting

| Kansans: | # Ballots |

| Approve | 1,731 |

| Disapprove | 46 |

Then comes the “Black Exclusion” vote, which would:

Ban Negroes and Mulattoes from settling within the state borders.

This vote is important because it indicates how many Kansans favor Free State status because of moral opposition to slavery versus on the basis of anti-black racism and/or simply self-interest as white men.

The margin here is closer, but still overwhelming – with voters choosing 3:1 in favor of cleansing their state of all blacks!

“Black Exclusion” Voting

| Kansans: | # Ballots |

| Approve | 1,287 |

| Disapprove | 453 |

This anti-black expression in Kansas is, however, not new. It follows the patterns set by prior constitutional debates in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and California, and presages an even more legally entrenched ban in the state of Oregon.

It reveals that white American across the North fear and diminish black Africans with nearly as much zeal as their Southern brethren. As one Free Soil clergyman puts it:

I kem to Kansas to live in a free state and I don’t want niggers a tramping over my grave.

Furthermore, it signals the belief that the “black problem” belongs to the “Slave Power” states, and should not be “carried” into the new territories out west.

The militia man, James Lane, certifies the results and announces that the state will now be governed according to the new Topeka by-laws.

Key Events In Kansas: 1854-55

| 1854 | Milestone |

| July 7 | Pierce names Reeder as first Territorial Governor in Kansas |

| July 20 | The Platte County Self-Defense Association founded by David Atchison |

| Nov 29 | Border Ruffians fraudulently elect pro-slavery JW Whitworth to the U.S. HouseReeder reluctantly confirms the voting results |

| 1855 | |

| March 30 | A second fraudulent vote results in a “Bogus Legislature” of pro-slavery men |

| April 6 | Reeder de-certifies illegal votes from six districts |

| June | Reeder travels to DC to seek Pierce’s support for a fair do-over election |

| July 2 | The Bogus Legislature convenes in Pawnee for their opening sessionBenjamin Stringfellow assaults Reeder for making unfavorable public remarks |

| Aug 4 | Free-Staters meet in Lawrence to plot a resistance strategy |

| Aug 14-15 | The Free State Party is founded in a convention at Big Springs Commitment made to write a constitution and submit for admission to Union |

| Aug 17 | Reeder is fired and Daniel Woodson becomes Acting Governor |

| Sept 7 | Wilson Shannon begins his service as 2nd Governor |

| Oct 1 | Pro-Slavers re-elect JW Whitworth as Representative to the U.S. House |

| Oct 7 | John Brown arrives in Kansas |

| Oct 8 | Free-Staters elect ex-Governor Reeder as their U.S. House representative |

| Nov 11 | Free State Party completes work on Topeka Constitution |

| Nov 21-27 | Wakarusa War signal threat of violence to come |

| Dec 15 | Voting passes Topeka Constitution and Black Exclusion clause |

With their Topeka Constitution approved, the Free State Party goes on to elect a second Governor and Legislature for the Kansas Territory, designed to oppose the bogus rule of the Pro-Slavers in Lecompton.

To do so, they hold a vote of January 15, 1856, administered across twelve polling place. This too is peaceful, as the Pro-Slavery opponents again ignore the voting as irrelevant – given their conviction that the “authorized” government is already in place.

With a turn-out around 1700 in total — with most actual residents of the state — the winning candidate for Governor is Charles Robinson who enjoys a 3:1 margin over his nearest opponent, despite his reputation as an abolitionist.

Since the plan is to immediately apply for admission to the Union under the Topeka Constitution, the party decides to also elect its two proposed U.S. Senators and one U.S. House member at the same time. The choices for Senator are the militia leader, James Henry Lane, and the ex-Governor, Andrew Reeder. Mark W. Delahay, a lawyer and newspaper editor from Leavenworth, is selected to represent Kansas in the U.S. House.

Finally, James Lane is chosen to head to Washington to present the Topeka Constitution to Congress, and lobby for the immediate admission to the Union.

The Political Spotlight In Washington Shines On The Kansas Conflict

As 1856 progresses, Franklin Pierce sees that his chance to be re-nominated at the Democrat’s June convention is being threatened by his inability to solve the crisis in Kansas.

Pierce has gambled his political future on the success of the May 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act to avoid a North-South schism over slavery. The result in Kansas, however, has been chaos.

First comes the elections stolen by the “Missouri Ruffians.” Then the dismissal of Governor Reeder and his defection to the Free State Party. Finally the Free State Party’s Topeka Constitution written and approved with a legislature all its own. The result the embarrassment of two competing governments operating in Kansas, and widespread criticism of Pierce’s “popsov solution” to slavery in the west.

Additional alarms for the President include the Democrat’s loss of 75 seats in the House in the mid-term elections, the selection of a Know-Nothing Speaker in Nathaniel Banks, and the early signs of a new Republican Party apparently dedicated to opposing “popular sovereignty” with an outright ban on the expansion of slavery.

These events finally force Pierce to take a public stand on Kansas. He does so on January 24, 1856 in a lengthy message to Congress titled “Disturbances In Kansas.” It begins by acknowledging that the current situation must change to avoid “grave exigencies:”

Circumstances have occurred to disturb the course of governmental organization in the

Territory of Kansas and…urgently to recommend the adoption by you of such measures

of legislation as the grave exigencies of the case appear to require.

Plans to organize the territory were agreed to way back on May 30, 1854, but progress was delayed by two factors: “maladministration” and “unjustifiable interference” in the process.

The organization of Kansas was long delayed, and has been attended with serious difficulties and embarrassments, partly the consequence of local maladministration and partly of the unjustifiable interference of the inhabitants of some of the States, foreign by residence, interests, and rights to the Territory.

Here he blames Governor Reeder for failure to “exercise constant vigilance” and for “violating the law” himself by his land speculation activities.

The governor, instead of exercising constant vigilance and putting forth all his energies to prevent or counteract the tendencies to illegality…allowed his attention to be diverted …which rendered it my duty in the sequel to remove him from the office.

The “interference,” he says, traced to “pernicious agitation” by “excited individuals” in the east attempting to impose their “social theories” related to slavery. This “awakened emotions” in Missouri which, he admits, led to “illegal and reprehensible counter movements.”

This interference…was one of …pernicious agitation on the subject of the condition of the colored persons held to service in some of the States…(by) excited individuals…in the attempt to propagate their social theories… (and) to prevent the free and natural action of its inhabitants in (Kansas’s) internal organization…Those designs and acts had the necessary consequence to awaken emotions of intense indignation in States near to the Territory of Kansas, and especially in the adjoining State of Missouri, whose domestic peace was thus the most directly endangered; but they are far from justifying the illegal and reprehensible counter movements which ensued.

But the elections went ahead anyway, and, while flawed, the Governor officially certified the results, making them “completely legal.”

Whatever irregularities may have occurred in the elections, it seems too late now to raise that question…. For all present purposes the legislative body (at Pawnee) thus constituted…the legitimate legislative assembly of the Territory.

At this point, according to Pierce, it was simply “too late” for opponents to write their own Topeka Constitution, elect their government, and request admission to the Union. These were all “revolutionary acts” and have no legal legitimacy.

Persons…without law, have undertaken to summon a convention for the purpose of transforming the Territory into a State, and have framed a constitution, adopted it, and under it elected a governor and other officers and a Representative to Congress…Our system affords no justification of revolutionary acts…(and) it is the duty of the people of Kansas to discountenance every act or purpose of resistance to its laws.

The existence of a separate government in Kansas is unlawful and Pierce vows to use whatever means are necessary to put it down, hopefully “without the effusion of blood.”

It will be my imperative duty to exert the whole power of the Federal Executive to support public order in the Territory.

Current Governor Shannon has the authority to resolve the matter, using force if need be.

The Constitution requiring him to take care that the laws of the United States be faithfully executed, if they be opposed in the Territory of Kansas he may…(rely on) posse commitatus ; and if that do not suffice… then he may call forth the militia of one or more States for that object, or employ for the same object any part of the land or naval force of the United States.

Pierce ends his message trying to walk a fine line between the Southern and Northern wings of his party. Those who favor slavery in Kansas are heartened by his outright dismissal of the Topeka Constitution; those who oppose it, hear a call for a new convention to start over, rather than acceptance of the fraudulent Pawnee legislature.

This, it seems to me, can best be accomplished by providing that when the inhabitants of Kansas may desire it and shall be of sufficient number to constitute a State, a convention of delegates, duly elected by the qualified voters, shall assemble to frame a constitution, and thus to prepare through regular and lawful means for its admission into the Union as a State.

I respectfully recommend the enactment of a law to that effect.

Two Political Powerhouses Square Off On Kansas

Despite Pierce’s January 24 speech, James Lane arrives in DC to submit the Free State Topeka Constitution for statehood. He does so on March 4, 1856 and sets off a flurry of speeches in Congress, most notably in the Senate between the Democrat, Stephen Douglas, and Henry Seward, the former Whig now turned Republican.

Like Pierce, Stephen Douglas’ political future hinges on defending “popular sovereignty” to the bitter end. In his March 12, 1856, speech to the Senate he concedes that the procedures used in Kansas were improper and that caused the existing disruption.

The solution Douglas proposes is to leave the status quo Pro-Slavery governing body in place until such time as the population of Kansas hits a threshold level of 93,000 residents (to qualify for one seat in the House) and to then hold a new convention to write a constitution and properly seek admission.

This “delay and start over” solution is music to Southern ears, since it would affirm Governor Shannon and the Pawnee legislature and allow slave owners to continue to entrench their presence across the state. Abolitionist editor Horace Greeley sees the proposal as Douglas’s attempt to win the presidential nomination at the June Democratic convention:

No man could have made his Report who did not mean to earn the gratitude of the Slave Power…. I shall consider Mr. Douglas henceforth an aspirant for the Cincinnati nomination….

A northern rebuttal to Douglas calls for dissolving the “bogus legislature” and immediately admitting Kansas under the Topeka Constitution. Praise for this option comes from the

growing number of anti-slavery senators, including Seward, Lyman Trumbull, Charles Sumner, Ben Wade, John Hale and Henry Wilson.

Meanwhile, most members of Congress remains appropriately baffled by the entire situation. Their response is to create a “Kansas Investigation Committee” to gather more objective facts on the matter, and recommend a solution. Three former Whig members of the House are chosen: John Sherman of Ohio, William Howard of Michigan and Mordecai Oliver of Missouri.

Douglas rejects this committee approach out of hand, announcing on March 17 that he will bring his Kansas bill – following the proper procedures of popular sovereignty — to the floor in three days. In turn, Henry Seward says he will counter will his own proposal.

On March 20, the “Little Giant” delivers a two hour diatribe aimed at bullying his adversaries into submission. He places the blame for the “unfortunate difficulties” in Kansas on the Free State Party, saying that the Topeka Constitution brought by James Lane is illegal.

This charge causes the equally volatile Lane to challenges Douglas to a duel unless he withdraws “all imputation upon the integrity of my action or motives.” Douglas deflects this

claiming “senatorial privilege” whereupon Lane publicly brands him a coward.

Douglas turns to what he calls the singular hypocrisy inherent in the Kansas vote favoring the “Black Exclusion” clause. How he asks can one pose as “an especial friend of the negro” and simultaneously deny them the right to “enter, live, or breathe in the proposed State of Kansas?”

He then reiterates his views on “the negro” which involve no such posturing:

We do not believe in the equality of the negro, socially or politically, with the white man…Our people (in Illinois) are a white people, our State is a white State, and we

mean to preserve the race pure, without any mixture with the negro.

He charges Ex-Kansas Governor Reeder with multiple blunders, first in certifying two fraudulent elections, then in reversing course. He labels Lyman Trumbull, his fellow senator from Illinois, a “captive of the Black Republican camp” for supporting admission.

Douglas again admits that the Missouri Ruffians were at fault for manipulating the voting process and reiterates his demand for starting over in Kansas using the proper popular sovereignty procedures.

With that the chamber now turns to Senator Henry Seward to make the case for the Free State Kansans. At fifty-five, Seward has been a political fixture since 1830 and is considered the front-runner for a presidential nomination in 1856. While rejecting the call for abolition, he is firmly opposed to slavery as he famously says, because “there is higher law than the Constitution.”

Seward’s speech opens with the claim that the true citizens of Kansas are living under a “foreign tyranny” imposed by pro-slavery forces in Missouri.

Armed bands of invaders established a complete and effective foreign tyranny over the people of the Territory…

He accuses Pierce of being an “accessory” to this “usurpation” and calls for his impeachment:

The President of the United States has been an accessory to these political transactions, with full complicity in regard to the purpose for which they were committed. He has adopted the usurpation, and made it his own, and he is now maintaining it with the military arm of the Republic. Thus Kansas …now lies subjugated and prostrate at the foot of the President (who) is forcibly introducing and establishing Slavery there, in contempt and defiance of the organic law.

To support his illegal actions, the President has misconstrued the words of the Constitution to defend slavery, and has compounded the error by dismissing the 1820 Missouri Compromise — and has now tried to silence the protest from the people of Kansas.

The President distorts the Constitution from its simple text, so as to make it expressly and directly defend, protect, and guaranty African Slavery…(and) to effect the abrogation of the prohibition of Slavery in Kansas, contained in the act of Congress of 1820. It thus appears that the President of the United States holds the people of Kansas prostrate and enslaved at his feet.

Seward says that the refusal to admit Kansas traces to the South’s efforts to try to impose its demands related to slavery on the rest of the nation. Despite its historical support from some compromised “Northern hands,” the effort has failed for over fifty years, and the time has come to give it up. If not, the threat of disunion threatens:

The solemnity of the occasion draws over our heads that cloud of disunion, which always arises’ whenever the subject of Slavery is agitated…The slave States…have been loyal hitherto, and I hope and trust they ever may remain so. But if disunion could ever come, it would come in the form of a secession of the slaveholding States.

The proper answer for Kansas lies in immediate admission under the Topeka Constitution, the only path consistent with the cause and values of the United States.

Let it never be forgotten, that the cause of the United States has always been (that) of Universal Freedom.

Congressional Opponents Turn To Violence

While most members of Congress are content to delay action until the “Kansas Investigation Committee” report becomes available in June 1856, one Senator is unwilling to wait without provoking his “Slave Power” colleagues.

That Senator is Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and he is fully primed in advance to lay into all who would allow slavery to spread to the west. In a note to his abolitionist colleague, Governor Salmon Chase of Ohio, he anticipates the upcoming moment:

I have the floor for next Monday on Kansas and I shall make the most thorough & complete speech of my life. My soul is rung by this outrage & I shall pour it forth.

“Pouring forth” in superior fashion on his moral certainties is a trait Sumner perfects early on in his life. After helping Salmon Chase found the Free Soil Party in 1848, he is elected to the Senate in 1850. Once in office, his sanctimonious lecturing and arrogant style become well known in congress, and are off-putting to many members across party lines.

The “The Crime in Kansas” he delivers lives up to that reputation. It becomes famous not for the arguments he makes about Kansas, but rather for the fury of his personal attacks on fellow senators, and the retribution which follows.

The speech, which runs five hours over two days, begins by calling upon President Pierce to redress the “crimes” to date in the territory, which Sumner lays out in detail. But along the way comes sustained ad hominin attacks on the character of two senators present in the chamber, whom he calls out by name. They are Senators Andrew Butler of South Carolina and Stephen Douglas of Illinois, co-authors of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Sumner’s speech is interrupted thirty-five times by Senator Butler, victim of a recent stroke that causes a slurring of his words. This prompts Sumner to mock his disability:

With regret, I come again upon Mr. Butler, who overflowed with rage at the simple suggestion that Kansas had applied for admission as a State; and, with incoherent phrases discharged the loose expectoration of his speech, now upon her representative, and then upon her people.

Many in the audience are dismayed by the obvious breech of parliamentary courtesy displayed by Sumner. Among them is Stephen Douglas, who reportedly says during the talk “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool.”

Two days after Sumner’s speech, Douglas’s comments prove prophetic.

Many southerners are outraged by the remarks, among them Preston Brooks of South Carolina, a second cousin to Butler, and a well-known hothead. After being talked out of challenging Sumner to a duel, he settles on a public beating instead.

It occurs on May 22, 1856. In the afternoon, Brooks, along with congressmen Lawrence Keitt and Henry Edmondson, enters a nearly empty Senate chamber and approaches Sumner, who is sitting at his desk writing letters. Brooks informs him that his speech has libeled his kinsmen, Butler, and, as Sumner tries to rise, he begins to beat him violently with his walking stick:

I…gave him about 30 first rate stripes. Toward the last he bellowed like a calf. I wore my cane out completely, but saved the head which is gold.

Keitt brandishes a pistol to deter those seeking to stop the attack before Sumner, bleeding profusely from head wounds, is dragged to safety. But the effects are long-lasting, and it will be over three years before Sumner returns to the Senate.

Word of Brooks’ assault becomes national news overnight, and the coverage reflects the growing antagonism between the North and the South. William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the New York Evening Post, characterizes Sumner as another martyr to the Slave Power:

The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and would stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder. Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them?

Hundreds of letters are sent to Sumner, some expressing sympathy for his martyrdom, others expressing intense anger toward the South and vowing revenge. Public protest meeting take place across the North, including some 5,000 people who show up on May 24 for a rally at Faneuil Hall.

Brooks on the other hand is hailed as a hero across the South, for “lashing the Senate’s vulgar abolitionists into submission.” Scores of citizens respond by sending him “replacement canes” to continue his good work.

After a House investigation, Brooks is expelled and Keitt is censured. By then, however, Brooks has resigned only to be re-elected by his constituents and returning to the House, before dying suddenly in January 1857 after a bout of the croup.

Back In Kansas The Warfare Intensifies

Sandwiched between Sumner’s “Crimes In Kansas” speech and his savage caning by Preston Brooks lies another turning point in the saga of Bloody Kansas, this time in the Free State capital of Lawrence.

At the center of this incident is the Sheriff of Dodge County, Samuel Jones, who is appointed in 1855 by the Pro-Slavery legislature. Free Staters in Lawrence call him the “bogus sheriff” and threaten him with death should he appear in town.

On May 21, 1856 Jones arrives in Lawrence along with a force of 700 militia and pro-slavery men and four cannons to carry out various arrest warrants. Confronted with this overwhelming firepower, the residents allow U.S. Deputy Marshal Fain to carry out his duties peacefully. Having completed the assignment, Fain dismisses the militia men from duty – which leaves Sheriff Jones and the remaining pro-slavery gang in place.

This is a second chance to wreak havoc on Lawrence and they take it. They sweep into town and begin by destroying the printing presses of the two leading newspapers, the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State. The Free State Hotel, headquarters of the resistance movement, is next, with ex-U.S. Senator David Atchison directing the fire of his four cannons. When the structure walls survive, kegs of powder are piled inside and the building is burned to the ground.

General looting follows, including the destruction of the home of Charles and Sarah Robinson, with Robinson already in jail since May 10 on charges of treason for his role as the Free Stater’s chosen Governor of Kansas.

As the invaders depart, Sheriff Sam Jones is said to exclaim:

This is the happiest day of my life, I assure you.

With the town of Lawrence still in a shambles from the Pro-Slavery assault, the Old Testament abolitionist, John Brown, responds with an eye for an eye in what becomes known as the “Potawatomie Massacre.”

Brown is fifty-six years old when he moves in October 1856 from his home in New Elba, New York to Potawatomie Creek, Kansas, to join several of his sons in the crusade against slavery.

Among his acolytes are members of his own family, and he calls upon four of his sons on May 24, 1856 to avenge the losses suffered three days earlier at Lawrence. It appears that they have two main targets in mind – a member of the Pro-Slavery legislature named Allen Wilkinson, and another man, “Dutch Henry” Sherman.

In their search for Wilkinson, they arrive first at the home of one James Doyle, a pro-slavery man living in Potawatomie. Together they haul the family out of bed and take three of them outside despite pleas for mercy from Mahala Doyle. The next day a younger son discovers what happened next:

I found my father and one brother, William, lying dead in the road, about two hundred

yards away. I saw my other brother lying dead on the ground, about one hundred and

fifty yards from the house, in the grass, near a ravine; his fingers were cut off, and his

arms were cut off; his head was cut open; there was a hole in his breast. William’s head

was cut open, and a hole was in his jaw, as though it was made by a knife, and a hole

was also in his side. My father was shot in the forehead and stabbed in the breast.

But that much bloodshed is not enough. After murdering the three Doyles, they locate Allen Wilkinson of the “bogus legislature.” His body is discovered the following day:

Next morning Mr. Wilkinson was found about one hundred and fifty yards from the house, in some dead brush. A lady who saw my husband’s body, said that there was a gash in his head and in his side; others said that he was cut in the throat twice. On the Wednesday following I left for fear of my life.

Four are now dead, but the savagery continues around 2am on the morning of May 25 when searching for their target, “Dutch Henry” Sherman, they come upon his brother, William who serves their blood lust:

William Sherman was dead in the creek…with his skull was split open in two places and some of his brains washed out by the water. A large hole was cut in his breast, and his left hand was cut off except a little piece of skin on one side.

As brutal as these attacks were, Brown is able to dismiss them as “righteous” in their intent. As he later says:

It is better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should pass away by a violent death than that slavery should live on.

But the killing of Brown’s five victims, accompanied by the gruesome character of their wounds and a certain sense of randomness to their fate, seems to signal that prior restraints need no longer apply to future confrontations.

From jail, Charles Robinson condemns Brown’s slaughter saying that it will only bring more federal troops against the Free State cause. But Brown is undeterred by the criticism, and organizes his Potawatomie Rifles Brigade to pursue the fight. His next target is U.S. Deputy Marshal H.C. Pate, who has arrested two of Brown’s son as hostages.

On June 2, Brown finds Pate and a band of some two dozen men camped at Black Jack, twenty miles south of Lawrence, along Captain’s Creek.

Along with Captain Samuel Shore’s brigade he attacks them shortly before dawn in a pitched battle which lasts for upwards of three hours. It ends when Brown slips several men into Pate’s rear, convincing him that reinforcements have appeared from Lawrence, and that he is surrounded. In response, Pate raises a white flag and surrenders along with twenty-three of his men. During the skirmish four of Brown’s men are wounded in action.

Brown proceeds to draft a formal “Article of Agreement” which calls for an exchange of prisoners: Brown’s two sons in return for Pate and his lieutenant, W. B. Brocket. Both sides sign and the battle is over. Some historians will later refer to this engagement at Black Jack as the “opening battle in the Civil War.”

Back on the political front, Pierce pays the price for the chaos in Kansas losing the nomination for president in 1856 to James Buchanan at the party convention in Cincinnati on June 6.

The Free State’s Topeka Constitution is front and center in Congress on July 2, 1856, when the “Kansas Investigation Committee” issues its report stating that the Pro-Slavery legislature seated in Lecompton “was an illegally constituted body, and had no power to pass valid laws”.

In turn, the House approves the Topeka Constitution by a 2 vote margin before the South is able to table it in the Senate.

An alarmed Franklin Pierce moves quickly against the Topeka supporters by sending Mexican War General Edwin “Bull” Sumner along with federal troops to shut down the Free State legislature. He arrives in Topeka during a 4th of July Day celebration, deploys his men, and calmly announces his orders from the President. When asked if a rejection will be met by “the bayonet,” he replies in the affirmative.

This intrusion of federal soldiers merely amps up the Free Stater’s commitment to organizing enough military force to achieve their ends.

To do so, they rely on the professional, “General” James Henry Lane, and the amateur, “Captain” John Brown. By early August the Free State militia – known alternatively as “Jayhawkers” or “Lane’s Brigade” – is sufficiently organized to go on the offensive. Its focus

will fall on three Ruffian strongholds: Forts Franklin, Saunders and Titus.

These “forts” are all modest affairs, no more than sizable storehouses, constructed of logs and guarded by sentries. Their purpose is to act as a meeting place for members of the Pro-Slavery Militia and an armory where weapons, currency and rations can be stored and accessed as needed.

The Jayhawkers hope to move swiftly against all three targets, with General Lane moving south from the Free State capital in Lawrence to capture Ft. Franklin and Ft. Saunders, and his second-in-command, “Captain” Samuel Walker, heading northwest against Ft. Titus, situated only one mile south of the Pro-Slavery town of Lecompton.

On August 12, 1856, General Lane, along with some 75 troopers, send a wagon load of hay on fire against the entrance to Ft. Franklin and sends the 20 defenders scurrying for their lives. Lane is victorious with 14 prisoners taken along with a canon, and over 50 muskets, rounds ammunition and foodstuffs.

The few who escape make their way some eight miles further south to Ft. Saunders, with Lane giving chase. Along the way, Lane’s fury is heightened by coming across the mutilated body of Free-State Major D.S. Hoyt of Lawrence. But word of his approach leads the pro-slavery men to abandon the fort before he gets there.

While Lane has been marauding south of Lawrence, his main force, purportedly 400 men strong under Colonel Samuel Walker, has traveled northwest from the capital toward Lecompton, a principal population center for the Missouri Ruffian settlers.

Walker’s objective is Ft. Titus, the residence of former West pointer “Colonel” Henry Titus who participates in the sack of Lawrence. The fort is especially important give its proximity to Lecompton and its treasure of some 400 muskets and $10,000 in gold bullion.

On August 16, 1856, Titus encounters an advance unit of Walker’s men heading toward the fort and engages them, losing one man killed in action. Clearly facing a much larger enemy force, Titus falls back to the fort for shelter, along with roughly twenty defenders.

A first uncoordinated attempt to rush the fort is repelled, with four Jayhawkers wounded and one killed. Firing continues for about a half hour until Walker brings up the cannon just captured at Ft. Franklin and aims it at the entrance to the fort. After seven rounds are fired, a white flag is flown signaling surrender. Walker’s effort pays off with the treasure of weapons and gold, along with 17 prisoners. He then burns Ft. Titus and prepares to head north toward Lecompton.

With the Jayhawkers near the outskirts of Lecompton, Governor Shannon appears in Lawrence in a last ditch effort to forestall the threat to the Pro-Slavery populace. As a powerful bargaining chip he brings with him Major John Sedgwick, twice breveted for heroic cavalry duty during the Mexican War and now a symbol of federal intervention in the Kansas conflicts.

While a flimsy truce agreement involving an exchange of prisoners is negotiated, Shannon’s tenure in Kansas is up. His life is threatened by both sides, and President Pierce finally recognizes that he is the wrong man for the job. On August 21 notification arrives of his removal from office. His subsequent comments sum up his frustrations over the eleven months he has served:

Govern Kansas in 1855 and ’56! You might as well attempt to govern the devil in hell.

Governor Geary Momentarily Calms The Waters

With Shannon out of the picture, Acting Governor David Woodson declares that Kansas is in a “state of insurrection” on August 25 and calls out the militia to restore order. But just five

days later a band of several hundred Border Ruffians strike the Free State town of Osawatomie and burn it to the ground. Among the casualties is John Brown’s son Fred who dies fighting futilely alongside his father.

On September 9, 1856 the third of what will become six Territorial Governors of Kansas arrives at Lecompton. He is John Geary an imposing figure, standing six foot six and weighing 260 lbs. He is a Pennsylvanian by birth, a college graduate in civil engineering and law, and a military man who wins lasting fame in the assault on Mexico City where he is wounded five times.

His first challenge comes quickly. On September 14, a six hour skirmish matches Lane’s Brigade against a band of Atchison’s Kickapoo Rangers at Hickory Point. The following day Geary himself rides there accompanied by federal troops and encounters a Pro-Slavery force preparing to invade the town. He quickly backs them down, saying they would first have to fight his army.

Geary is clearly the right man for the job in Kansas, if only he can tolerate the incompetence he finds with the politicians in Washington.

The final political event during 1856 in Kansas takes place on October 6 with the re-election of a pro-slavery legislature in another vote boycotted by the Free Staters.

This is followed by the November 4 presidential election which will determine the course of the Kansas crisis over the next four years and make the Civil War inevitable.

The winner is Democrat James Buchanan who garners 112 of 120 Electoral Votes in the Slave States along with another 62 of 176 in the Free States for the victory over his Republican opponent, John Fremont. Like Pierce, Buchanan is a dedicated “doughface,” born in the north (Pennsylvania) but favoring southern positions to advance his political ambitions.

His top priority entering office is to curtail the Free State movement in Kansas and insure that it is admitted to the Union as a Slave State.

Key Events Impacting Kansas: 1856

| 1856 | Milestone |

| Jan 15 | Free-Staters elect their own Governor and Legislature |

| Jan 24 | Pierce declares the Topeka government invalid and revolutionary |

| March 4 | James Lane in DC to request admission under Topeka documents |

| March 12 | Douglas attacks Topeka and calls for starting over on “popsov” |

| March 17 | Douglas proposes bill outlining a proper process to admit Kansas |

| March 19 | Cong sets up “Kansas Investigation Committee” |

| April 9 | Seward attacks Pierce; offers Topeka; SD balks; Lane challenges |

| April 18 | Three man ”Kansas Investigation Committee” arrives in Kans |

| April 19 | Sheriff Samuel Jones shot in back in Lawrence, badly wounded |

| May 5 | Judge Samuel Lecompte’s arrest warrants for Reeder & Robinson |

| May 18-19 | Sumner speech: “The Crime Against Kansas” |

| May 21 | Pro-Slavers sack the town of Lawrence |

| May 22 | Sumner caned in Senate by Preston Brooks |

| May 24 | Charles Robinson captured in Missouri and jailed in Lecompton |

| May 24-25 | John Brown’s massacre at Potawatomie |

| June 2-6 | Democratic Convention chooses Buchanan |

| June 4 | Battle of Black Jack (called “the first battle of the civil war”) |

| June 15 | Northern Know-Nothings nominate Banks, then Fremont |

| June 17-19 | Republicans also choose Fremont |

| June 23 | Toombs Bill calls for another constitutional convention in Kansas |

| July 2 | Kansas Investigation Committee report cites the fraudulent elections in KansasThe Topeka Constitution passes in the House but is tabled in the Senate |

| July 3 | Senate passes Toombs Bill 33-12; House rejects it and votes 99-97 to admit Kansas; stalemate follows |

| July 4 | Col. Edwin Sumner disbands Topeka (Free-State) legislature |

| Aug 15 | Fort Saunders captured by Lane and Free-State men |

| Aug 16 | Fort Titus burned by Lane and Free-State men |

| Aug 18 | Congress recesses without any action on KansasGov. Shannon removed from office. |

| Aug 25 | Acting Gov. Woodson declares Kansas Territory in open rebellion |

| Aug 30 | Pro-Slavers defeat Brown at Battle of Osawatomie |

| Sept 9 | John Geary begins his term as Governor |

| Sept 13-14 | Battle of Hickory Point |

| Sept 15 | Geary and U.S. troops stop pro-slavery militia threat at Lawrence |

| Oct 6 | Annual election of Kansas legislators is boycotted by Free-StatersPro-Slavery representatives remain in power at Lecompton |

| Nov 4 | James Buchanan elected president |

As the pivotal year of 1857 opens, Governor Geary’s commitment to an even-handed application of popular sovereignty in Kansas is tested by William Sherrard. He is a pro-slavery native of Virginia, whose election to succeed Samuel Jones as Sheriff overseeing the Free State town of Lawrence is overturned by Geary. Sherrard is outraged, threatens to assassinate Geary, and at a hearing on February 18, 1857 to review his case, he fires a shot before being killed by a bodyguard in the room.

This becomes one more incident that provokes General Geary to resign on March 12, 1857. In hindsight he cites two reasons for withdrawing after only six months of service: first, unreliable support from the Pierce administration; second, the demoralizing effects of watching the “depravity” exhibited by both sides in the fight.

I have learned more of the depravity of my fellow man than I ever before knew…I have thought my California experience was strong, but I believe my Kansas experience cannot be beaten.

But history will judge Geary to be the most capable of the six Governors in the history of “Bloody Kansas.”

Just prior to Geary’s departure, the U.S. Supreme Courts under Roger B. Taney issues its ruling in the eleven year-long Dred Scott case. It says that as a negro, Scott cannot become a U.S. citizen and therefore has no standing in court. He is the “property” of his owner and has no personal rights other than those granted by that owner. Furthermore, the federal government cannot prohibit owners from taking their slave property to any territory they choose – and therefore the 36’30” demarcation line in the 1820 Missouri Compromise is unconstitutional.

Buchanan applauds the verdict and argues naively that it should end all further debate over slavery, both in Kansas and nationally, for good. But two of the Supreme Court Justices write defiant dissents which lead the Republicans to argue that Dred Scott is not settled law. It is also regarded in the North as a threat to the Northwest Ordinance demarcation line which would “nationalize slavery.” As such the ruling is largely ignored going forward.

Buchanan Names A New Governor

The President turns to naming a new Governor in Kansas to replace Geary. He chooses 55 year old Robert J. Walker, a trusted Democrat, former U.S. Senator, and a successful Secretary of the Treasury under James Polk. His pro-Southern credentials are also well established. After practicing law in Pittsburgh, he moves to Natchez, Mississippi, becomes a slave owner and trader, and supports nullification in 1832 along with aggressive policies toward territorial expansion.

On the face of it, the diminutive Walker (five feet tall and one hundred pounds) looks up to the task, despite inheriting two diametrically opposed political parties, each with its own legislature, and each claiming to represent the will of the Kansas people:

- One group, the Pro-Slavery forces, now operating as members of his Democratic Party, chosen in an annual election on October 6, 1856, boycotted by their opponents. They are scheduled to meet in September 1857 at the town of Lecompton to write an official state constitution.

- They are opposed by the Free State Party, whose “renegade” legislature has reconvened at Topeka on January 7, 1857, after being disbanded by Colonel Sumner and his U.S. troops back on July 4, 1856.

Buchanan’s instructions to Walker are quite clear: first, shut down the Topeka operation for good; second, get the Lecompton body to write a Constitution that has Kansas admitted to the Union as a Slave State, both to restore order there and to cater to his Southern base.

There are, however, genuine political risks associated with the President’s plan.

One is that the Lecompton Slave State document might alienate his support among the northern wing of his Democratic Party. This concern is particularly relevant in the U.S. House, where he will need solid northern support to pass a bill to admit Kansas.

Another risk is even more troublesome. While the Dred Scott ruling seems to negate the need for additional popsov voting in Kansas, the promise of “let the people decide” has stood as a central plank of the Democrat Party since 1848. To simply discard it now would violate the expectations and support of citizens in Kansas and nationwide.

On top of that, deep down Buchanan and his southern backers also fear that the majority of those actually residing in Kansas may oppose the presence within their borders of not only slaves, but all blacks, and will thus vote in favor of a Free State designation.

Within this context, Robert Walker arrives in Kansas on May 27, 1857.

His welcoming address manages to upset both sides in the disputes. He slams the Free Staters as a mix of fanatical abolitionists – “who would threaten not only Kansas but the Union” – and utter hypocrites eager to ban all Negroes from ever residing in their state. He then dismisses their opponents for engaging in dangerous warfare over land whose climate he says is unfit for slavery and cotton.

Although Walker wants to do Buchanan’s bidding, the longer he is in Kansas, the more uncomfortable he becomes with the tactics used by the pro-slavery forces in tampering with elections. He may be from Mississippi and a slave owner himself, but he is also a former U.S. District Court judge and one dedicated to the rule of law. (He will even stay with the Union when the war comes.)

Thus he makes two important promises. First that any Constitution written will be voted on by all Kansans before submission to Washington for statehood. Second that both parties should focus on winning the “official election” for legislative seats scheduled for October 1857.

To the surprise of most, the Free State Party takes Walker at his word and instead of trying to operate a separate government of their own, they prepare to win the “official election” for a Kansas Legislature. This move will seal their ultimate political victory.

It catches the Pro-Slavers by surprise, and when the polls open on October 5, 1857 they are left without their strong-arm bands in place to control the outcome. All that’s left to them is a last second and obvious attempt to steal the election by stuffing the ballot boxes in several districts they control.

The blatancy of their actions pushes Walker over the edge. When he reviews the initial vote counts it is obvious that in two Districts the number of ballots reportedly cast for the Democratic Party bears no resemblance to the number of actual residents. Walker’s reaction is courageous: in Johnson County he throws out some 1400 Democratic votes and in McGhee County he invalidates 1200 more.

The result is a solid 2:1 vote victory for the Free-State Party – a profound outcome which, if allowed to stand, will hand them control of the “official” Kansas Legislature.

Governor Walker now heads to Washington to explain his actions to a very dismayed President Buchanan who shocks him by asking for his resignation, effective December 15, 1857.

But Walker is not so easily brushed aside given his very distinguished reputation in the capital. His exit is accompanied by a tirade against the President for betraying the popular sovereignty principles that were central to Democrat Party pledges and to Walker’s acceptance of the post in the first place. Worse yet, Walker appears at northern rallies against Lecompton, accusing Buchanan of “tyranny” for denying Kansans their right to a fair election.

While shaken by Walker’s aggression, Buchanan is undeterred in his commitment to gain congressional approval for the Lecompton Constitution and the entry of Kansas as a Slave State. Failure to do so will all but eliminate his chances for re-election in 1860.

The President decides to use his annual address to Congress on December 8, 1857 to make his case.

By the time he prepares, Southerners are already threatening secession unless Kansas is admitted as a slave state. Among them is James Henry Hammond, the newly elected Senator from South Carolina, who writes:

Save the Union if you can. But rather than have Kansas refused admission under the Lecompton Constitution, let it perish in blood and fire.

Southerners want the President to call for the immediate admission of Kansas as a Slave State under the Lecompton Constitution. Since he knows this will not work, he offers a tortuous reprise of the events to date. He ignores the fraudulent vote that Walker overturned and instead defends the Lecompton document and the actions of the Pro-Slavery Party with one exception. Namely, they failed to follow his instructions to submit the full constitution to the people before submitting it to Congress.

Thus while the Lecompton document was approved, the addendum – “with slavery or without slavery” – wasn’t presented for a vote. This procedural oversight is what, he says, needs to be corrected at the upcoming December 21 election.

Stephen Douglas Turns Against Buchanan

At this point Stephen Douglas has had enough of Buchanan’s transparent attempts to bully the Lecompton Constitution through Kansans and the Congress.

For weeks Douglas has been calling for the President to walk away from the Lecompton fiasco and start the entire process all over. But Buchanan will have none of that, accusing Douglas of disloyalty and threatening him with political reprisals should he fail to get in line.

Douglas is outraged by Buchanan’s tactics and, despite the risks of dividing the Democrat Party and harming his chances of becoming President, he decides to fight back. His speech to the Senate on December 9 asserts that Buchanan’s interpretation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was a “fundamental error,” as was his proposal to hold another vote on the Lecompton admission.

Nine days later he introduces a new bill to rerun the entire popular sovereignty process in Kansas from scratch.

As the December 21 vote is about to be cast in Kansas, James Denver arrives to replace Robert Walker as Territorial Governor. Denver is a Mexican War vet who has been serving as Buchanan’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs. As a former resident of Missouri he is also familiar with the history of the region.

Like his predecessors, Denver is immediately greeted with another rigged election. The Free State supporters boycott the Lecompton vote while the Pro-Slavery forces again stuff the ballots to signal is popularity.

December 21 Vote For Lecompton Constitution

| With Slavery | Without Slavery |

| 6,134 | 569 |

As 1857 closes, Buchanan thinks the December 21 outcome is the victory he has been seeking.

Key Events Impacting Kansas: 1857

| Dates | Milestone |

| Jan 7 | Topeka legislature reconvenes in defiance of prior shutdown |

| Jan 11 | “Law and Order Party” now called the National Democrats |

| Jan 12 | New legislators meet at Lecompton |

| Jan 19 | Geary denies appointment of Sherrard as Sheriff |

| Feb 18 | Sherrard killed after firing his gun during a hearing |

| March 4 | James Buchanan becomes President |

| March 10 | Topeka members reinstate Charles Robinson as Governor |

| March 20 | Governor Geary resigns |

| May 27 | New Governor Robert J. Walker arrives in Kansas |

| June 6 | Walker urges Free-Staters to abandon Topeka movement |

| Mid-June | Election of delegates for Lecompton Constitutional convention Free-Staters boycott and Pro-Slavery left in charge |

| June 25 | John Brown (aka Shubel Morgan) returns to Kansas |

| July 15 | Walker declares Lawrence in rebellion for re-opening legislature |

| Aug 20 | Charles Robinson finally acquitted of treason charges |

| Sept 7-11 | Constitutional Convention opens at Lecompton packed with Pro-Slavers |

| Sept 18 | Oregon passes its Free State Constitution which includes a ban on all blacks from residing within its territory. |

| Oct 5 | First fair election of Kansas legislators, with Free-Staters participating. Walker throws out fraudulent Pro-Slavery ballots and Free- Staters win a majority of seats and now control “authorized” legislature |

| Oct 19 | Lecompton Convention reconvenes to write a Constitution |

| Nov 7 | Lecompton adopts a pro-slavery document & sets Dec 21 vote on “with slavery vs. without slavery,” but not on full Constitution |

| Nov 16 | Walker goes to DC to explain the October 5 election results to Buchanan. Acting Governor Frederick Stanton fills in for him in Kansas |

| Dec 8 | Buchanan supports the Lecompton Constitution in annual message to Congress |

| Dec 9 | Stephen Douglas shocks Buchanan by announcing his opposition to Lecompton |

| Dec 15 | Walker sacked; blames Buchanan tyranny; says Lecompton was not real popsov submission and violated the right of self-government |

| Dec 21 | Governor Denver arrives and another fraudulent election approves the Lecompton Constitution “With Slavery” to the delight of Buchanan |

But the President’s belief is shaken two weeks later on January 4, 1858, when another general election is held in Kansas, this time without interference from the Missouri Ruffians.

A little over 10,000 ballots are cast that day by actual residents of Kansas, voting fairly and freely on the Lecompton Constitution. The first issue is whether to accept or reject it, and the answer is a resounding “No.”

January 4 Vote On The Lecompton Constitution

| Reject | Accept |

| 10,266 | 162 |

The second issue goes beyond that to select representatives to the official Kansas Legislature. The results here are never counted after a pro-slavery observer named John Calhoun manages to escape with the ballots. But Governor Denver steps in and informs Buchanan that the Free State candidates have won by a large margin.

With this outcome, the Free State Party solidifies its position as the fairly elected government in Kansas.

Still, Buchanan chooses to ignore the January 4 rejection, despite growing opposition from Northern Democrats, including those in his home state of Pennsylvania. On February 2, he brazenly goes ahead and asks Congress to admit Kansas under the Lecompton constitution.

As a smokescreen for this, he charges Speaker of the House, James Orr of South Carolina, to convene another select committee to review and assess the Kansas elections history. A brawl on the floor of the House ensues over the selection of committee members and the scope of the inquiry. The two initial pugilists are Lawrence Keitt of South Carolina and Pennsylvanian, Galusha Grow. It begins with a heated exchange:

Keitt to Grow: “you are a damned, black Republican puppy.”

Grow to Keitt: “no negro-driver shall crack his whip over me.”

Some thirty members join the melee, including Wisconsin’s John “Bowie Knife” Potter, who lands a punch on Indiana’s John Davis with one hand, and on William Barksdale, with the other. When Barksdale responds by grabbing hold of Cadwallader Washburn, he is struck by a blow that dislodges his wig – a humorous sight that finally causes the weary combatants to cease.

Speaker Orr is undeterred and proceeds to stack the select committee with pro-slavery sympathizers. After a brief perfunctory “investigation,” its report totally ignores the interference of the Border Ruffians in the process; claims that the delegates who wrote the Lecompton document were representative Kansans selected in legal fashion; and says that the election of December 21, 1857 signaling support for the “Constitution With Slavery” was legitimate.