Section #5 - The Mexican War

The Mexican War: 1846-47

The Early History Of New Spain

Before there was Mexico there was New Spain, the product of Hernando Cortez’ conquest of the Aztecs in 1521. The land he claims for Spain is massive: some 529,000 square miles in North America covering the future states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming.

For three centuries, this land is ruled by two factions: the Catholic Church and politicians, split between aristocratic Peninsulares (born in Spain) and Criollos (born locally). This lasts until Napoleon conquers Spain in 1808, which triggers revolutionary fervor throughout the Americas.

In New Spain the revolt is led by a priest, Miguel Hidalgo, living in the town of Dolores. In September 1810 he issues his moving “Grito (Cry) of Dolores” calling for the overthrow of the government. While Hidalgo is charged with treason and executed in 1811, his cause lives on. The next in line is Criollo Augustin de Iturbide, a military man who begins as a loyalist, switches to the rebel side, and, with Church support, is crowned Emperor of Mexico in 1821. His reign, however, is brief, and in 1823 he is exiled to Spain by those supporting a republican form of government. In 1824 Iturbide foolishly returns to Mexico where he is executed for treason.

From 1825 to 1829, General Guadalupe Victoria serves as the first President of Mexico, despite constant political infighting and attempted coups. General Vicente Guerrero follows, but only for nine months before being overthrown by General Anastasio Bustamante who lasts until 1833. He is toppled by strongman Lopez de Santa Anna who begins his long in-and-out control over Mexico that runs to 1847 and beyond.

The Migration Of Americans And Their Slaves Into Mexican Lands

Throughout this time, the northern Mexican lands remain sparsely populated, mostly by those living at Catholic missions. This fact is noted by American frontiersmen like Miles Austin who gains approval from Mexican authorities in 1822 to purchase 4600 acres along the Brazos River. He deeds the land to his son, Stephen, who founds a settlement known as the “Old Three Hundred” for the number of land parcels passed out. By 1825 some 1,790 Americans settlers reside there along with 443 slaves.

From then on, tension grows between Austin’s men and the Mexican government. First over slavery, which is banned in 1829 by President Guerrero. Then in 1830, when President Bustamante prohibits further immigration from the U.S., and Austin is imprisoned for two years for protesting the order.

By 1835, there at 35,000 “Texians” in the Coahuila y Tejas province of Mexico along with some 5000 enslaved blacks, now called “indentured servants for life” to skirt the ban on their presence. When the settlers move west toward the San Antonio River, President Lopez de Santa Anna is further alarmed and commits to driving the Americans out.

The Republic Of Texas Is Founded In 1836

The first open clash occurs on October 2, 1835, when Mexican cavalry troops attempt to retrieve two cannons loaned to settlers in the town of Gonzales to combat Commanche raids. A brief skirmish follows with the Texians retaining the cannon and only a few casualties on either side. But word of the incident reaches border newspapers where some call it the “Texas Lexington,” after the initial battle of the Revolutionary War.

Santa Anna begins his campaign to cleanse the Texians by assaulting a small band holed up at the Alamo mission near San Antonio de Bexar. His 1500 troops begin to siege the garrison on February 23 under a “no prisoners” Red Flag.

As the conflict plays out, a previously planned convention of settlers meet at “Washington-on-the-Brazos” on March 2 and declare their independence as a new nation. They christen it the Republic of Texas, sanction chattel slavery, and elect David Burnet, an early settler and political leader, as their acting President.

Meanwhile, at the Alamo, Santa Anna’s forces have grown to 3,000 men while the Texians are able to muster only 260, including Congressman Davy Crockett and James Bowie. On March 6 the Mexicans break through the outer walls and trap the remaining Texians inside the inner compound. By 6:00am they have slaughtered the entire garrison, shooting or bayoneting any left wounded or captured.

But Santa Anna’s fury is not over, and it plays out on March 27, 1836, at the town of Goliad, some 90 miles southeast of the Alamo. After his troops win battles at Refugio and Coleto, he assembles the 400 captured prisoners of war and executes them all by firing squads.

When word of the Alamo and Goliad atrocities become know, the Texians turn to Sam Houston for revenge. Houston has led an up and down career, starting as a lawyer, then a US Congressmen and Governor of Tennessee before his marriage falls apart and he earns his Indian nickname, “Big Drunk.” But after coming to Texas in 1832 he rehabilitates himself and is given command of the Republic’s army just prior to the Alamo.

His strategy is to retreat to the east to give his army time to get organized for an offensive.

By April, he is all the way back across the Brazos River to San Jacinto 250 miles east of the Alamo, and is criticized by U.S. officials in Washington. Santa Anna sees this as proof that the Texans are fleeing Mexico and he catches up to them on April 20 at the San Jacinto River.

The terrain is marked by thick forests and marshes and the armies encamp some 500 yards apart. On April 21, Santa Anna’s 1250 troops are poorly deployed, and when Houston’s 800 man force fails to attack first thing, they are allowed to break for food, rest and bathes. Which is when Houston strikes, beginning with an opening barrage at 4:00pm from the two cannon (christened the “Twin Sisters) retained at Gonzales, and followed by a four-pronged charge with fixed bayonets and shouts of “Remember the Alamo.” The Mexicans flee for their lives and the entire fight is over in less than twenty minutes. The rout ends with 650 Mexican soldiers killed and 300 captured against Texan casualties of only 41, including Houston who suffers a gunshot wound to his left ankle.

The day after the battle Santa Anna is captured in the nearby marshes and is brought to meet with Houston. The result is the Treaties of Velasco, recognizing the independence of Texas in exchange for his safe passage to Vera Cruz. But when Mexico City learns of the outcome, Santa Anna is relieved of his presidency and the treaty declared null and void.

The Battle of San Jacinto is a landmark victory for the Republic of Texas, but by no means ends the open hostility between the Mexicans and Texans.

The Ongoing U.S. Debate Over Annexating Texas

After Sam Houston becomes the first president of the Republic in October 1836, lobbying begins in Washington to have Texas join the Union as the 26th state. Andrew Jackson, Houston’s friend and field commander during the War of 1812, favors the annexation but proceeds cautiously. He sends a commissary, Henry Morfit, to assess conditions in Texas and to recommend a course of action. Morfit’s report cites three reasons to hold off:

- Annexation would almost certainly lead to a war with Mexico;

- As the 14th Slave State (vs. 12 Free) it would heighten regional animosity; and

- Fixing financial shortfalls in Texas would require sizable government expenditures.

Jackson is most worried over the slavery issue and, in rejecting the annexation appeal, he holds true to his famous 1830 quote, “the federal Union must and shall be preserved.” His successor, Martin Van Buren, agrees and support wanes.

But it doesn’t disappear. In 1837, Congress officially recognizes Texas as an independent nation. In 1838, South Carolina Senator William Preston introduces a bill to negotiate an annexation treaty with Mexico and Texas which is vigorously opposed in the House by John Quincy Adams, citing his opposition to warfare and to slavery. By 1839 the disheartened Texans break off unification talks and decide to continue on their own.

Tensions rise again on September 11, 1842 when the Texas town of San Antonio is sacked and occupied, and a year later when Santa Anna, restored to the presidency, declares that annexation would lead be regarded as a declaration of war.

The threat falls on deaf ears at the White House where “His Accidency,” John Tyler, has become the first Vice-President to take over upon the sudden death of William Henry Harrison. Tyler is a Virginian by birth, an outcast from the Whig Party that nominated him, and eager to find an issue with enough popular support to win the top spot on the Democrat Party ticket in 1844. He views annexation as that issue and orders John C. Calhoun, his new Secretary of State and a rabid proponent of slavery, to gain Congressional approval of four principles:

- Texas would enter the Union as a state, and not a territory;

- It would be allowed to retain slavery;

- The U.S. would assume its national debts, in exchange for its public lands; and

- The U.S. would be obligated to defend Texas against any attacks by Mexico.

To rally additional support for the legislation two threats are raised: the possibility of Texas aligning with Britain and taking over the entire west; and Calhoun’s call for “Texas or Disunion.” Despite both, Congress refuses to go along. The bill loses in the Senate by 16-35, with the Whigs’ opposition reinforced by the Democrat powerhouse, Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri (a “no” vote that will eventually cost him his seat).

The “Manifest Destiny” Craze Helps Pass The Annexation Bill

But the defeat is short-lived as the 1844 campaign for the presidency heats up. Tyler and Calhoun both continue to favor annexation and they are helped along by a cultural phenomenon known as “manifest destiny,” an idea put forth by the journalist, William O’Sullivan. In words reminiscent of the “shining city” metaphor of Puritan minister, Jonathan Edwards, and of the Founders themselves, O’Sullivan proclaims:

It is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of

the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great

experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.

The notion that territorial expansion to the west coast is needed to signal the moral superiority of republican democracy remains in dispute in Washington. But the appeal of more open land to the west – be it for farming or to advance slavery – gains widespread public support.

Neither of the two front-runners for the 1844 nomination – the Whig, Henry Clay, and the Democrat, Martin Van Buren – recognize the extent of public support for Texas Annexation early on. When they do, it’s too late, and Van Buren loses the nomination to the “dark horse” James Knox Polk, while Clay loses to him in the election.

Unlike his Tennessee mentor, Andrew Jackson, Polk is unequivocally in favor of annexation. With his support, the lame duck Congress passes the Texas Annexation Bill on March 1, 1845, by a narrow 2 vote majority in the Senate and a wide margin in the House. Opponents like the abolitionist Joshua Giddings of Ohio point directly to the evils of the southern “Slavocracy” to explain the outcome:

Texas is engaged in a war with Mexico and wants us to fight her battles…

and a portion of this House says, we will do it, if, by that means, we can keep

up slavery in Texas and thereby furnish a market for our slave-breeding states

to sell their surplus population.

The Mexican government is predictably outraged by passage of the bill, and doubly so because it involves not only Texas proper (north and west of the Nueces River), but also another huge area of “claimed land” south to the Rio Grande. (Some politicians even assert that the Texas land was included in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.)

The Mexicans officially signal their anger on March 6, 1845, two days after Polk’s inauguration, by recalling their minister and severing diplomatic relations with Washington.

Polk Sends U.S. Troops To Defend The Texas Border

Anticipating possible hostilities, the President in May 1845 sends General Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops to the Nueces River border of Texas “for defensive purposes.” With the death of Polk’s long-time mentor, Andrew Jackson, June 8, 1845, “Young Hickory” is left to deal with the potential crisis on his own.

Strained relations continue until October, when Mexican President Jose Herrera, who hopes to avoid war, signals that he is willing to engage in talks about border issues, by which he means a Texas Republic Treaty. Polk seizes upon this apparent “opening” to not only resolve the “claimed land” borders to the Rio Grande, but also to explore Mexico’s willingness to part with additional territory west to California.

Louisiana Senator John Slidell is chosen by Polk as Minister to Mexico on November 10, and is sent on a mission to negotiate a trade of land for money – the Rio Grande border in exchange for forgiving a $3.5 million Mexican debt owed the U.S., the New Mexico territory for $5 million, and the ports of San Francisco and Monterrey for another $20 million. He is also directed to inform Herrera that the U.S. would intervene in any move by Mexico to sell this land to a foreign power, such as Britain or France.

On November 29, 1845, Slidell arrives at the gulf port of Veracruz, ready to engage Herrera in Mexico City. But Herrera’s tenure in office is about to end, as the hawkish General Mariano Paredes, who had previously ousted Santa Anna, marches on the capitol and takes power on December 30. Slidell is now left in a holding pattern, waiting to learn Paredes’ stance on the border issues.

Polk, however, is not in a waiting mood. When news of Paredes stalling tactics reach him on January 12, 1846, he orders Taylor’s forces to advance further southwest. The move crosses Mexico’s claimed eastern border at the Nueces River, some 150 miles west to the Rio Grande. Paredes sees this as an invasion of Mexican territory and fires back by refusing to accept Slidell’s credentials as a diplomat. After standing idly by for over three months, the treaty mission officially ends in March 1846.

Meanwhile Taylor’s troops, now 3,500 men strong, are strung out along the north bank of the Rio Grande opposite the town of Matamoros, on the other side of the river. On April 24, 1846, they are attacked by Mexican forces, with sixteen Americans killed in action.

On May 8, Slidell is back in Washington briefing Polk and his cabinet on his failed mission to Mexico City. The President finds “ample cause for war” in Parades’ treatment of Slidell, and is in the process of drafting a message to congress, when word reaches him that fighting has already broken out.

The U.S. Declares War And The Fighting Begins

Polk responds by sending up a declaration of war to Congress on May 13, 1846, arguing that the Mexicans attacked Taylor on American soil east of the Rio Grande. With first blood already spilled, he is confident that any pacifists will now be ready to act. In the end, his assessment proves right, and the yays are 40-2 in the Senate and 174-14 in the House.

Underneath, however, many reservations exist. The crafty Calhoun abstains, fearing that an outcome where federal opposition to slavery might result. A small cluster of House Whigs led by JQ Adams, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, and Jacob Brinkerhoff of Ohio join the avowed abolitionist Joshua Giddings in labeling the conflict an “aggressive, unholy, unjust war.” Other Whigs justify their support as the only way to “repel the Mexican invasion.”

(But was there, if fact, a Mexican invasion? In December 1847 freshman congressman Abraham Lincoln challenges Polk’s rationale, demanding to know the “exact spot” where the first American was killed, and proof that land east of the Rio Grande was legally American soil. The implication of this “spot speech” being that America, not Mexico, was the aggressor in the war and that the intervention was unnecessary to defend Texas.)

Regardless of the rationale, on the day war with Mexico is declared, America’s military force is anemic. Despite its actual and often anticipated conflicts with Britain, the notion of a large standing army is still seen by many as a potential threat to preserving the nation’s democracy. Should any war break out, the fighting is to be done by a volunteer militia, led by a small Regular Army corps.

On May 13, 1846, muster for the Regular Army stands at a mere 6,562 men comprising 14 regiments, with eight infantry, four artillery and two dragoons (mounted troops). To bolster this count, Polk asks Congress to fund an additional 50,000 volunteers.

On top of the need for more volunteers, Polk faces another challenge in deciding who should command his expeditionary army. The obvious choice as overall leader is Major General Winfield Scott, who has served the nation since 1809, and is the ranking officer in the army since his June 1841 promotion. But he is an outspoken critic of slavery and a Whig who has already been considered for the presidency in 1840, before the nomination of William Henry Harrison. As such Polk views him more as a political competitor than a military subordinate.

Given this, Polk decides to leave Brigadier General Zachary Taylor in command, since he is already in action on the Rio Grande and, unlike Scott, professes no interest in politics, at least so far.

As the war begins, Taylor’s initial strategy is two-fold:

- Meet and defeat the Mexican forces at the southern tip of the Rio Grande, and then move inland to the immediate west; and

- Send troops to occupy the northern provinces of New Mexico and Alto California so these can become U.S. territory when the conflict is over.

Taylor Wins A String Of Early Victories

The hard fighting is under way for ten days before the official May 13 declaration passes Congress. For the Mexicans, their first objective is a star-shaped earthen defense outpost that Taylor’s troops have built on the east side of the Rio Grande. It is christened Ft. Texas, and later re-named Ft. Brown, after the heroic major who falls there. It is occupied by only 500 U.S. troops, and General Mariano Avista begins to shell it on May 3 from his side of the river in Matamoros. He then advances across the river, surrounds the fort, and begins an all-out siege.

After five days of steady bombardment, the fort is still holding out, when Avista learns that General Taylor, stationed 22 miles away to the east at Fort Isabel, is coming his way with 2200 men and 150 wagons to relieve the pressure. General Avista halts the siege and pivots the troops he has north of Ft. Texas, heading out along the Point Isabel Road to intercept Taylor.

Taylor is outnumbered by Avista – on the order of two to one — when the armies meet on May 8 on an open plain bordering the high chaparral, or shrub land, known as Palo Alto. The action is particularly bloody, since neither side entrenches and there are no natural walls or fences to provide protection from artillery fire. Over a five hour period, repeated changes by the Mexican infantry and dragoons are repulsed by the American’s “flying artillery,” lightweight cannon with exploding shells maneuvered by horses to critical areas of the field. Avista finally abandons his attack, with casualties upwards of 600 killed or wounded vs. Taylor’s losses reported at 4 killed and 37 wounded.

The Mexicans fall back in good order on the morning of May 9 to defensive fortifications they have previously prepared five miles back along the Point Isabel road to Fort Texas. Taylor chases after him.

Fronting the Point Isabel road is an ancient run-off channel of the Rio Grande, known locally as Resaca de la Palma, a ravine with waist-deep water surrounded by palm trees and other shrubs. Arista locates his HQ to the south while arraying his troops along the arc of the ravine, both west and east of the road. His position is a strong one, and Taylor attacks it head on from the northwest.

One of his young lieutenants is Ulysses S. Grant, who describes his early assault as follows:

I was with the right wing and led my company through the thicket wherever a

penetrable place could be found…that would carry me to the enemy. At last I

got pretty close up without knowing it. The balls commenced to whistle very

thick overhead cutting the limbs of the chaparral left and right.

Another later-to-be-famous warrior, Lt. James Longstreet, offers his memories of the fight:

The battalion came to the body of a young Mexican woman. This sad spectacle

unnerved us a little, but the crush through the thorny bushes brought us back to

thoughts of heavy work…All of the enemy’s artillery opened, and soon his musketry.

The lines closed in to short work, even to bayonet work at places.

The Americans continue this “heavy work” against the Mexican lines throughout the afternoon. They finally break through after a small force under Captain Robert Buchanan flanks the defender’s left wing and comes up in the rear of Arista’s men. This surprise infiltration collapses the Mexican’s line, wins the battle, and initiates a panicked 200 mile retreat due west to their bastion at Monterrey.

During the two days of fighting, the Americans suffer 34 killed and 113 wounded, while the Mexicans lose over 1500 men, killed, wounded or drowned during flight, along with the capture of 7 major artillery pieces. With these opening victories, the Americans secure the Rio Grande border, demonstrate their tactical superiority on the battlefield, and prepare to drive further west into the interior of Mexico.

The “Wilmot Proviso” A Political Bombshell Interupts Progress

While Polk is pleased by General Taylor’s victories south of the Rio Grande, his sights remain set on taking all of the land he sent Congressman John Slidell to negotiate with the Mexicans. To do so he asks Congress in August for an additional $2million to fund the war.

On August 8, 1846, a first-year congressman from Pennsylvania named David Wilmot responds with an amendment that shocks his fellow Democrats and reveals the hostility of Northerners toward expanding slavery into the west. “Wilmot’s Proviso” announces that he will support the expenditure but only:

Provided that, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any

territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty

which may be negotiated between them, and to the use by the Executive of the

moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever

exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first

be duly convicted.

The Proviso is everything feared about the war by Union-first men like Jackson and southern slave holders like Calhoun. It passes in the House, but is tabled in the Senate. Over the next decade, however, it will divide the North from the South, spawn new political parties, lead to violence in Kansas and ultimately end with secession and civil war.

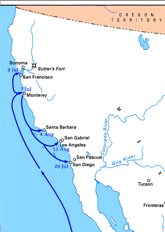

America Grabs Alta California

Polk is undeterred by Wilmot’s Proviso and expands the scope of the war beyond the border of Texas and over to Mexican territory on the west coast. He sends American warships to blockade the Pacific coast ports and orders Colonel Stephen B. Kearney to march from Kansas toward Alta California. Kearney is a battle tested fifty year old who begins his military career in the War of 1812, helps explore the West, and then earns fame as the “father of the U.S. Cavalry” for decades of service protecting settlers across the Great Plains.

Kearny rides out of Leavenworth on June 3, with 1700 men and his immediate sights set on reaching Santa Fe, some 750 miles to the west. Before he gets there, Polk’s quest for control of California is almost resolved through the actions of a band of local settlers around Sacramento, aided by the western adventurer, Captain John C. Fremont.

On June 8, 1846, Fremont, Kit Carson and 55 armed troopers are encamped near Sutter’s Fort, in the Sacramento Valley, near Yuba City. They have arrived there after Fremont’s third expedition – mapping the route of the Arkansas River – has morphed into a yearlong journey into the Oregon Country and then down into Alta California, where he makes contact with American settlers in the region. The Mexicans regard Fremont as a nuisance and chase him back into Oregon for a period of time. But as word reaches him of possible hostilities, he re-positions his troops back in the valley.

I saw the way opening clear before me. War with Mexico was inevitable; and

a grand opportunity presented itself to realize in their fullest extent the far-

sighted views of Senator Benton. I resolved to move forward on the opportunity

and return forthwith to the Sacramento valley in order to bring to bear all the

influence I could command.

Once there, he is approached by local Americans who claim that Mexican troops are about to drive all foreign settlers out of Sacramento. They ask Fremont if he would be willing to support them in establishing a Texas-like republic. Fremont encourages them and they plunge forward, assembling and equipping their own thirty man posse and heading back toward San Francisco to launch a military-style filibuster. On June 14, 1846, they arrive at the sleepy Mexican outpost in Sonoma, some 45 miles north of the port city, and surround the home of General Mariano Vallejo, “Commandante of Northern California.” They proceed to arrest both Vallejo and his brother, and declare their new status as an independent nation.

A white bedsheet serves as their makeshift flag, painted across the top with the outline of a California grizzly bear and a single red star, mimicking Texas. On July 1, the “Bear Flag” rebels, now under Fremont’s direct leadership, reach San Francisco and occupy the Presidio compound, which is undefended. At first they raise their banner over the works, but within days it is replaced by the stars and stripes. This ends the brief history of the “Bear Flag Revolt” and begins the de facto seizure of Alta California from the Mexicans.

While the “Bear Flag” land grab is playing out in California during June-July 1846, further U.S. incursions into Mexico are under way. On August 15, 1846, General Stephen Kearny captures Sante Fe, the capital of the province of New Mexico, without firing a shot.

Taylor Takes Monterrey

In September, finds the Mexican Army holed up at Monterrey, an enclave of 10,000 inhabitants, and the capital of Nuevo Leone province. The city sits in a valley surrounded on two sides by the 4,000 foot peaks of the Mitre mountains, with the Santa Catarina River running along its eastern and southern flanks. Its location along the main road through the mountains toward Saltillo makes it strategically important to the westward advance of Zachary Taylor’s army.

Monterrey is also well protected by a series of redoubts and stone buildings that dot the roads in from the northeast. General Ampudia concentrates his 9,000 troops across these fortifications, and confidently awaits the Americans. On June 12 Taylor learns they are dug in at Monterrey and he sets three divisions and some 6600 troops in motion. After studying the ground, he settles on a daring two-prong attack. Generals Quitman and Twiggs will send the bulk of the army headlong at the heavily defended fortresses north and east of the city.

Colonel John Garland, leading Twigg’s division, opens the battle against the eastern fortifications, with support from Mississippi and Tennessee units under Quitman and Colonel Jefferson Davis. They capture Fort de al Teneria and the bridge leading over the river to Ft. Diablo. Ohio troops under General Butler join the attack on Diablo, but it is successfully defended throughout the day by General Ampudia’s forces. After ferocious street to street combat the Americans have gained a solid toehold on the eastern side of the city by nightfall.

Progress to the west is even greater, with the hero of the day being Captain Charles F. Smith, who leads his four companies up a spur of Mt. Mitre known as Federacion Hill, drives off the Mexican defenders, and turns decisive artillery fire down on the city. As the first day of battle to the west ends, General Worth is poised to invade Monterrey from the west.

Overnight, General Ampudia decides to abandon Ft. Diablo, and draw back all his forces to the Cathedral and Central Plaza area, for a last stand. At daybreak on September 23, General Quitman and a force of Texas Rangers find Ft. Diablo empty and race past it into the city, with shouts of “Alamo and Goliad.” ringing through the streets. General Worth hears the early sounds of battle and sends his troops forward to capture the western end of the city and envelop the remaining Mexicans. They quickly take the Bishop’s Palace outpost and begin house to house fighting. By nightfall Worth has reached to within one block of the Plaza, and is in contact with Quitman and his troops, now nearby.

The fates of the Mexican army and of the city of Monterrey are sealed – and General Ampudia knows it. On the night of September 23, he approaches General Worth for “terms of surrender.” In exchange for the city, Taylor allows Ampudia to evacuate his army, along with its small arms provided that any further conflict is suspended for the next six weeks. When word of this deal filters back to Washington, Polk wants to relieve Taylor of his command, despite the victory.

Important Battles of the Mexican War In 1846

| 1846 | Battle | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| May 3 | Matamoros | US | 80 | Mexican attack on US fort repelled |

| May 8 | Palo Alto | US | 310 | US artillery carries the day |

| May 9 | Resaca de la Palma | US | 640 | Taylorsecures Rio Grande border |

| June 14 | Bear Flag Revolt | US | — | Fremont captures Alto California |

| Aug 15 | Santa Fe | US | none | Kearney takes NM city without a shot |

| Sept 23 | Monterrey | US | 900 | Crushing defeat for General Ampudia |

With the string of victories in hand, the question becomes one of what it will take to bring the war to closure. This topic is hotly debated within Polk’s cabinet. As usual, the President is clear about his preference – to expand the invasion until the enemy gives in. His cabinet, led by the ever bothersome Secretary of State, James Buchanan, and the War minister, William Marcy, object to his proposal for three reasons:

- A broader invasion will extend the fighting and produce more agitation in Congress;

- They do not believe that General Winfield Scott is up to the task of leading the troops; and

- Both Scott and Taylor are Whigs who might run for president in 1848.

Polk floats out the possibility of promoting Senator Benton of Missouri to Lieutenant General, ranking Scott, but he backs off when others resist. As the cabinet ponders options to end the war, critics begin to assert that Polk’s hidden intent is to conquer all of Mexico, absorb it into the United States, and create a host of new Slave States. Polk flatly rejects these charges, but this assurance isn’t enough for the skeptics in congress – who again wave the Wilmot proviso in the face of the President and the Southerners.

War In The North Ends At Buena Vista

After scoring his decisive victory at Monterrey on September 23, 1846, General Zachary Taylor’s orders from Washington are to consolidate his hold on Monterrey. Instead he continues westward, taking the town of Saltillo on November 16, and ordering General John Wool to move south to Aqua Nuevo, where he arrives on December 21.

As Taylor drifts further into the interior, Mexican General Ampudia is sacked in favor of the familiar figure of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. His is a chequered past, starting with early support of Spanish rule, then flipping sides after independence is won in 1821 and finally defeating Spain’s attempt to reconquer Mexico at the 1829 Battle of Tampico. This victory makes him a national hero and leads to a political career, whereby he is in and out of the presidency on seven occasions, his last term ending in exile to Cuba after a coup.

But in late 1846 he again “offers his services to the country” to put down the American invaders – just as he did in March 1836 defeating the Texans at The Alamo and then in the Goliad Massacre. With his return comes a guarantee to the government to stay out of politics, and a secret hint to the U.S. that he is ready to sign a peace treaty.

He quickly abandons both promises, retaking political control in 1847 and fighting tooth and nail against the U.S. invaders. Santa Anna remains a courageous warrior, despite the loss of his left leg to a cannon ball in 1838. He is a sound military planner, and also confident of victory – believing that he can first destroy Taylor’s depleted forces up north and then sweep down south on any invaders aiming at Mexico City.

General Taylor appears to play right into Santa Anna’s hand on February 22, 1847 when his 5,000 man force, heading toward Aqua Nuevo, suddenly finds Santa Anna’s 20,000 man army directly in his front. Taylor responds quickly by establishing a strong defensive position along the road leading back north to Buena Vista. On the west side of the road are impassable plateaus, while on the east side, where Taylor deploys, are a series of arroyos, or deep gullies, which inhibit massed infantry attacks. Still Santa Anna remains so confident of victory that he sends an emissary to seek immediate surrender – which Taylor promptly declines.

At 8AM on February 23, the Mexicans launch a ferocious two-pronged attack. The main body of their infantry crashes into Taylor’s left center which wavers until pivotal artillery support from Lt. George Thomas and Captain Braxton Bragg stiffens the defense. Meanwhile another contingent of roughly 1500 lancers head far east and north to encircle the American’s left flank. These lancers break through and pose a serious threat to Taylor’s rear – until a courageous rush by Colonel Jefferson Davis and his 7th Mississippi Rifles hurls them back. Santa Anna still believes by mid-afternoon that the U.S. forces will break under one more concentrated assault.

At 5PM he throws everything he has left against the American center and again forces it backwards until Bragg’s flying artillery and Davis’s infantry are once again able to save the day.

The butcher’s bill for the day of fighting on February 23 is high – with 3700 men killed/wounded/missing on the Mexican side and 750 on the American side. Braxton Bragg (1817-1876) Two U.S. heroes emerge from the battle. The first is Zachary Taylor, who, despite disobeying orders and marching into a 4:1 manpower trap, has escaped with another victory to close out his campaign to secure the Rio Grande border for Texas. The second, ironically, is Taylor’s son-in-law, Jefferson Davis, who suffers a severe wound to his foot at Buena Vista, ending his military duty and leaving him on crutches for two years. He returns as a hero, and is chosen by Governor Brown serve in the U.S. Senate, which is vacant by a death in office. Davis joins the Senate on August 10, 1847 and immediately becomes a leader in the Democratic Party.

When Santa Anna retreats from Buena Vista on February 24, 1847, his Mexicans will have come as close to securing a battlefield victory as any time during the entire war. But henceforth the conflict will turn to the south.

Scott’s Plan To End The War

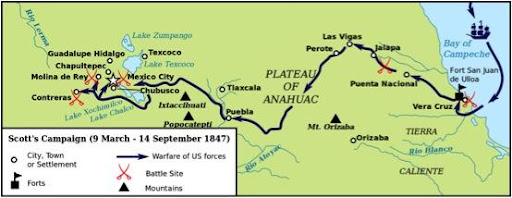

As political controversies over the war swirl about Washington, General Scott steps forward with a plan to win it. He will assemble and personally lead an invasion force of some 14,000 troops, capture the port city of Veracruz, then march overland to overwhelm and occupy the capital of Mexico City. Polk reluctantly adopts the plan, and orders go out for Taylor to hold his position at Monterrey, while detaching the bulk of his army to join up with Scott’s invasion force. The fate of the President’s war now rest in the hands of two Whig Generals, both of whom he distrusts as military commanders and as potential political opponents of his Democratic Party.

Two weeks after Taylor’s victory at Buena Vista, Scott executes America’s first major amphibious invasion, landing some 11,000 American troops on Sacrificios Island, just below the fortress city of Veracruz, with its garrison of 4,400 troops under General Juan Morales and some 5,000 local civilians.

The terrain leading into Veracruz is marked by the high chaparral and deep arroyos typical of Mexico’s landscape. In addition to these natural obstacles, cannon are arrayed along a 15 foot high stone wall encircling the city and the road in is guarded by the formidable castle of San Juan D’Ulloa, and another 1,000 troops. Scott immediately decides to siege the city and assigns

Colonel Joseph Totten to oversee the plan, along with help from a 40-year old engineer, Captain Robert E. Lee. Lee’s placements of three 32 pound naval guns, hauled on land, will prove critical as the siege develops. Aside from Lee, several other soon to be famous West Pointers experience their first taste of battle at Veracruz, including Thomas Jonathan Jackson and George McClellan.

On March 22 Scott is ready to launch an all-out bombardment from land and sea, but, before beginning, he asks Morales to surrender. When the offer is refused, Scott begins his attack. The results are devastating. For three days Veracruz suffers under constant barrages from field artillery and naval guns. Mortars lob solid iron balls weighing upwards of 30 lbs. into the city from the west. In the bay to the east, the U.S. fleet unleashes its Paixhans guns, with 68 lb. shells that whistle in at low trajectories and explode on contact. Some 6700 shot and shell weighing over 450,000 lbs. rain down on the defenders. Naval officer Sydney Smith Lee, Robert’s older brother, observes the action from his frigate:

The battery’s fire was terrific… constant and regular discharges, so beautiful in their

flight and so destructive in their fall. It was awful! My heart bled for the inhabitants.

By March 25, the buildings and walls of Veracruz are crumbling and morale has worn thin. When Morale’s finally requests a truce to evacuate civilians, Scott refuses, insisting on a full surrender. After haggling, the final details are worked out on March 29. Scott’s siege has lasted 20 days, and he has sustained a mere 58 casualties.

The Siege of Veracruz is the most widely covered battle in the war, and newspaper accounts of the devastation increases discomfort with the war among many Americans. Reported atrocities add to the guilt, including one at Agua Nueva, where 20-30 refugees hiding in a cave are murdered and scalped by Arkansas troops in revenge for the loss of one of their own.

Scott’s gaze now shifts toward Mexico City, 225 miles inland. He knows that this will not be an easy target. His army will be outnumbered along the way, and fall further distant from its supply base as it marches off. His enemy will have superior knowledge of the terrain ahead, and be motivated by fighting on and for its homeland. Still the General is confident of success. He also knows from studying Napoleon that strict discipline in the ranks will be required to avoid alienating the local population and provoking partisan activity. His General Order 20 outlines harsh penalties for all Americans, soldiers or civilians, involved in robbery, rape, murder, destruction of property, and any acts affecting Catholic churches and worship.

After securing Veracruz, Scott sends a lead force of 8,500 men out of the city on April 8, heading northwest along the national road, with General David Twiggs and his 2nd Division in the lead. Six days later they are on the winding road to Xalapa, where Santa Anna plans to ambush and kill them. The Mexican General knows this ground particularly well, since it lies on his vast 30 mile long private estate. His plan is to lure the U.S. troops into a cul du sac formed by the Rio del Plana flowing along his right flank and the 950 foot high Cerro Gordo (“fat hill”) guarding his immediate left. He arrays the bulk of his 12,000 troops in a classical L-shaped formation, with artillery batteries and infantry scattered across the Jalapa road and additional units ready to fire down from the Cerro Gordo on his left.

He also stations troops along a plateau to the east of the road, hoping to lure the Americans in or close off their subsequent line of retreat. With this shooting gallery in place, the Mexicans await the U.S. columns. But Twiggs and his West Point engineers know an ambush when they see one, and they halt on April 14, north of the bend in the road leading down into Santa Anna’s position. After scouting the area, they settle on a plan involving a trap of their own. It hinges on enveloping the Mexicans, by hacking out a new road across the gullies and plateaus north of Santa Anna’s left flank, without being discovered. The work requires three full days to complete.

On April 17 Scott divides his army and advances. His light left wing, under Polk’s ex-law partner, General Gideon Pillow’s, demonstrates against the Mexican forces east of the road, while his main body, comprising Twiggs’ and Worth’s divisions, swoop down on Santa Anna from behind Cerro Gordo. Battery placements by Lt. George B. McClellan prove especially galling to the Mexicans, and the Lieutenant is cited for valor during the assault. By nightfall the surprised Mexicans are desperately trying to organize a credible defensive line.

As daybreak dawns on April 18, Colonel William Harney and his First Brigade dragoons deprive them of all hope — clawing their way to the top of Cerro Gordo and occupying the fortress there known as the Tower. From this vantage point, American artillery now dominates the entire field below. Once the American flag appears atop the Tower, Santa Anna knows that his position is hopeless. His troops along the eastern plateau surrender to Pillow’s command, and Santa Anna himself barely escapes with his life, on foot, amidst a panicked general retreat west toward Jalapa.

His losses are steep. Over 1100 Mexicans fall in the battle, and 3000 prisoners are taken, including five general officers. Another substantial depletion in artillery, smaller arms and ammunition also further weakens their capacity to fight on.

Scott’s Wins At Veracruz And Cerro Gordo Prompt Treaty Talks

Scott’s successes on the battlefield lead Polk and his cabinet to step up their plans for negotiating a treaty to end the conflict. The issues center on how much land they can convince the Mexicans to give up, and at what price. The cabinet agrees that an ideal outcome would involve all territory west, from where the upper Rio Grande touches New Mexico, to the Pacific – at a price not to exceed $30 million. Secretary of War Marcy drafts an outline of the plan, to be delivered to Scott by Nicholas Twist, the number two official at the state department under Buchanan.

Twist arrives at Veracruz on May 6 on the start of what will be a long and rocky mission. By this time, Scott’s army has chased the Mexicans all the way from Cerro Gordo to Puebla, only 80 miles east of the capital. This produces a mood within Mexico City itself that is a mixture of outrage and panic. After finally driving out the Spaniards to win independence, here comes another foreign invader – and a Protestant-dominated one at that – in search of conquest.

Calls go up in the capital to sack the government, declare martial law, draft all able-bodied men, commence guerrilla warfare. The last thing Scott wants to hear is talk of a religious war involving guerrilla bands operating outside the boundaries of conventional warfare. On May 8, 1847, he issues a carefully worded proclamation to the people of Mexico. It asserts that the war is with government leaders, not with the people; that it’s about policy, not religion; and that, once ended, the Americans will exit Mexico, not occupy it. With these reassurances comes a warning. Scott’s army is powerful and about to double in size, and it would be wise for the population to stay peacefully in their homes until the fighting is over

Truth be told, however, Scott’s army in May is much less prepared to advance on the capital than he lets on. The inevitable diseases that plague troops in the field have taken their toll, and the enlistment term for several volunteer regiments is about to expire. With his battle-ready forces under 6,000 men, he pauses in place at Puebla for eight weeks awaiting reinforcements.

General Scott’s pause after his victories at Vera Cruz and Cerro Gordo allows time for envoy Nicholas Trist to negotiate for peace, and for him to add more men before moving further inland toward his next goal, Mexico City. The first contingent of 2,000 troops arrives in July, followed soon by another 2,400, under Brigadier General Franklin Pierce. On August 10, 1847, Scott decides that he is ready, and his total force of 10,700 men – half new untested volunteers – heads west.

Soon they are cresting the mountains east of the capital where they come upon a dazzling landscape in the valley below. There, at 7250 feet above sea level, lays the city built by the Aztecs in 1325 and ruled by them until Cortez overthrows Montezuma in 1519. Scott now must decide how he plans to conquer the capital city. By August 16 he has reconnoitered the direct approach from the east over the National Road through El Penon Viejo, and concluded that it will leave him with only one line of assault on the capital. So he settles instead on a difficult 27 mile march heading south of Lake Chalcothen east along the Acapulco Road. He intends to bypass the Mexican defenses there, march around the Padregal lava fields to the town of Contreras, and attack north from there.

Santa Anna, however, anticipates Scott’s path and intends to attack him along the road from Contreras to Churubusco. He lays out strong positions over the entire route, with General Valencia’s 7,000 men on a steep hill bordering Contreras, his own 11,000 men two miles to the north, General Ruicon with another 6,000 at Churubusco, guarding a river bridge, and General Bravo with 3,000 men above San Antonio. Once again, as at Cerro Gordo, Santa Anna is confident of victory. His 27,000 soldiers outnumber Scott by 3:1, and they are fighting to protect the capital city of their nation. But Scott finds a way to outmaneuver and defeat the Mexicans, despite their courageous efforts.

Coming up first against Valencia on August 19, General Persifor Smith’s brigade is beaten back and left in a trapped position at the foot of the Contreras hill. That night Valencia celebrates, passing out brevets along with hard liquor to his troops. As the Mexicans revel, Smith’s engineers find a way out of their trap – a passable ravine that circles to the right of the hill and comes up on Valencia’s rear. At 3AM on the 20th, Smith’s men race up the slopes and a rout ensues. According to Smith, it has “taken just 17 minutes” to clear the Mexicans off the hill and send them scurrying toward Churubusco. Santa Anna tries to stabilize his troops throughout the day, but to no avail. General William Worth forces his way through the Mexican left and unites with Twiggs and Pillow at Churubusco. They are slowed briefly by stiff resistance from a heavily fortified church convent, but soon break through and seize the key bridge over the Churubusco River.

The first line of defense protecting the capital city has been breached by Scott in his three victories on August 20, 1847. American casualties for the day total 120 killed and 816 wounded. The Mexicans suffer 3,250 total casualties, along with 2,627 prisoners.

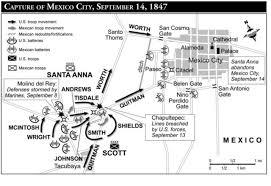

Scott Conquers Mexico City To End The Fighting

Four and a half months have elapsed since U.S. forces left Veracruz on their audacious mission. Now all that’s left is one final push. But instead of rushing headlong to the capital, Scott turns momentarily cautious. He fears that his army has been fought out at Churubusco, and wants time for his engineers to plot the best approaches into the city. When he halts, Santa Anna sends emissaries out under a flag of truce to explore an armistice. Buchanan’s man, Twist, joins the talks, and soon the lull in battle reaches two weeks. By then Scott concludes that Santa Anna is simply stalling for time to strengthen his defenses, and he ends the armistice on September 7. His army is refitted and his strategy laid out. On September 8, 1847, he resumes his advance.

The ancient city now in Scott’s front is built originally on an island just off the western edge of Lake Texcoco. By the late 17th century, the population is expanding and the lake is being drained away to prevent flooding and provide more living space. Eventually the lake vanishes into marshland, with eight elevated causeways built as routes into the city. To reach the interior, Scott must first overcome three formidable outposts guarding the entrance to the western causeways – the citadel at Casa de Mata, the Molino del Rey mill and foundry, and the daunting Chapultec Castle, regarded by many as the strongest fort on the North American continent. A bitter dispute over strategy for attacking the Molino erupts here between Scott and General William Worth, his right hand man going all the way back to the War of 1812. Scott prevails, but Worth never fully forgives him for the carnage that follows.

At dawn on September 8, Lt. John Foster leads the first head-on attempt to storm the Molino. This ends in a hail of musket fire and grapeshot that repulses the Americans and leaves Foster lying with a shattered leg on the field. And there he stays for another two hours of sustained violence in what turns out to be one of the bloodiest battles of the war. The Americans eventually prevail at both the Molino and the Casa de Mata citadel, but at a cost of 729 casualties, including 58 officers. The Mexican losses top 3,000, with Santa Anna’s top two commanders killed outright, General Leon at Molino and General Valderez at de Mata.

With the Molino secured, Scott decides that he will storm the capitol from two directions. His main attack will come from the west, under General Pillow, along the six foot high causeway leading to the San Cosme (customs house) Gate. Pillow will be supported by infantry units under the Mississippi General, John Quitman, driving from the south against the Belen Gate. To succeed, Pillow must first pass the Chapultepec Castle, jutting out on a rock ledge 150 feet above the ground, surrounded by walls that are 4 feet thick and 20 feet high. The castle, formerly home to Aztec emperors, is now the site of the Mexican Military Academy, their West Point.

But not even this imposing barrier can hold up under the advanced artillery hardware and engineering tactics that have helped the Americans prevail from one battle to the next. On September 12, four U.S. batteries, in easy range and well sheltered, begin to reduce the fort’s defenses. On September 13, as the bombardment continues, the Americans storm Chapultepec. Pillow’s troops race through the Molino grounds and into a cypress grove, where the General falls with a severe wound to his ankle. His men, however, move steadily forward and deploy scaling ladders to begin their ascent of the rocky hill leading to the castle itself. One officer who particularly distinguishes himself in this action is Lt. Tom Jackson (later Stonewall), who wins another brevet for his artillery work alongside Captain John Magruder.

Pillow’s troops are quickly joined by General Quitman coming up from the other side of the hill. Both contingents encounter fierce resistance, but nothing is about to deny the Americans at this point. By late morning shouts go up across the battlefield as the Stars & Stripes appear on the castle ramparts. During this brave assault on the castle, a litany of future civil war military heroes have suffered wounds. Lt. PGT Beauregard is hit twice in the action. Major William Loring loses his left arm. Second Lt. James Longstreet goes down with a bullet to his thigh while carrying a regimental flag he hands off to Lt. George Pickett. Others wounded include Lt. Colonel Joseph Johnston, Captains Silas Casey and Magruder, Lts. Innis Palmer, Lewis Armistead, Earl Van Dorn, Isaac Stevens, and John Brannan.

The Mexican troops are both astonished and demoralized by the fall of Chapultepec, and they flee east along the two major causeways toward the central city. The Americans follow post haste – with Worth picking up the lead for Pillow toward the San Cosme Gate, and Quitman’s forces, under the wounded General James Shields, closing on Belen. Shields is a hot-headed Irish politician from Springfield, Illinois, who, in 1842, had challenged Abraham Lincoln to duel over a perceived slight. His battle temper is similarly up as he chases after the Mexicans, and he breaks through Belen and into the city proper by 1PM, only to come under heavy fire from the Citadel in the central Plaza. By evening Shields and Quitman are hunkered down and waiting on Scott’s next orders.

Worth’s drive toward San Cosme proves to be much slower going, despite courageous initiatives from men like Second Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant, who sets up a howitzer in the belfry of a church and scatters defenders in his front. Rearguard skirmishes and sniper fire continue on this causeway throughout the afternoon, and Worth halts his men by 8PM within easy artillery range of his assigned gate.

The scene is now set for the climax of Scott’s campaign to occupy Mexico City, which began on March 9, with the landing at Veracruz. September 14 opens with the sight of emissaries from the city coming out to meet Scott. They inform him that Santa Anna has resigned his presidency and that the main body of the Mexican army has fled overnight out the backdoor exit along the National Road. They also request that control over the population, some 200,000 strong, be assigned to municipal authorities and the church.

Scott has not come this far to leave the capital in Mexican hands, and he immediately orders his troops forward. The right wing, under Quitman and Shields, are already inside the city, and they proceed rapidly toward the Grand Plaza and the National Palace, seat of the Mexican government. Once there, General Quitman is given the honor of raising the American flag in the square.

Clean-up operations against diehards continue over the next day and a half, until the morning of September 16, when control over the entire city has been secured. On September 16, 1847, Scott names Quitman military governor of Mexico City, a position he will hold all the way until July 20, 1848 when the U.S. occupation ends. At the same time, Scott allows the local city council to continue to function, along with the local police force and justice system. The Americans fine the city 150,000 pesos to care for wounded soldiers, and insure payment by controlling the customs gates. Eventually some of the funds collected go against efforts to rebuild the city.

Since entering the Valley of Mexico on August 10 with 10,700 troops, Scott has suffered 2,703 killed or wounded, including 383 officers. Mexican losses are pegged at 7,000 total casualties, along with 3,700 prisoners. When asked about “why” his massively outnumbered forces have prevailed in Mexico, Scott points to the superior military training and leadership of his West Point officer corps.

I give it as my fixed opinion, but that but for our graduated cadets the war between the

United States and Mexico might, and probably would, have lasted some four or five years…

whereas in two campaigns we conquered a great country and (won) peace without the loss

of a single battle or skirmish. If West Point had only produced the Corps of Engineers, the

country ought to be proud of that institution.

The 78 year old Duke of Wellington, victor at Waterloo, attributes the victory to Scott, calling him “the greatest living soldier” and his Mexican expedition “unsurpassed in military annals.” On the other hand, General Pillow declares himself the “hero of Chapultepec” and is court marshaled by Scott, along with Worth, for writing after-battle reports considered self-laudatory and unprofessional. Scott’s attention now turns to working toward a peace treaty, in conjunction with Nicholas Twist.

By the winter of 1847, Polk realized that winning the war with Mexico has not ended the political battles surrounding the original annexation of Texas and the Wilmot Proviso ban on slavery in land acquired by the conflict. Even within his own Democratic Party, divisions run deep about what to do with Mexico and its territory. James Buchanan, who publicly opposed any land acquisition when the war began, now turns acquisitive, to boost his odds for the presidential nomination Polk’s Treasury Secretary, Robert Walker, wants to annex the entire country.. Once again Polk is enraged by his erratic Secretary of State, Senator John C. Calhoun, whose hawkishness over Texas provoked the war, expresses horror at this thought which would blemish America’s racial purity.

We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race

– the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of

(including) an Indian race. Ours, sir, is the government of the white man…To erect

these Mexicans into a territorial government and place them on an equality with

the people of the United States is (something) I protest.

Then there is the especially galling New York wing of the party, now being called the “Wilmot Proviso Democrats,” who continue to insist on the slavery ban. Polk himself opposes a wholesale annexation, but argues that America must be “indemnified” (i.e. compensated) for the costs of a war Mexico started by “their invading U.S. soil” along the Rio Grande on April 25, 1846. He decides to “wait out” the Mexicans, hoping they will offer up attractive peace terms.

He has sent his version of the territorial boundaries he favors to Nicholas Trist of the State Department, to advance talks toward a treaty. But gradually he learns that Trist is negotiating on his own terms, with potential concessions in Texas and Alta (upper) California that Polk opposes. He also hears that Scott has court marshaled his confidante, Pillow, and joined Trist in working out a treaty, including a possible $1 million bribe to Santa Anna. At this point, Polk concludes that the time has come to sack both Trist and Scott — but he is emotionally so averse to personal confrontations that both men stay on by default.

Polk’s troubles from his Democrats are now matched by an increasingly vocal Whig opposition, with its 116-112 majority in the House. On November 13, 1847, Henry Clay lays out the Whig position in a speech in Lexington, Kentucky. The war was one of “aggression,” not defense, initiated by Polk’s false claim that Mexico invaded U.S. land. The end must not lie in annexing all of Mexico or in any extension of slavery into new land. Hearing these words, Polk’s supporters label Clay a convert to the abolitionist movement.

As the second session of the 30th Congress convenes, Clay’s arguments are amplified in two addresses by the 38 year old freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. As a young man, he has devoted his energy to building a law practice in Springfield, raising a family while dabbling in local politics, serving four terms in the Illinois House. In 1846, he is elected to the US House as the only Whig in a delegation dominated by Douglas and his Democrats. Lincoln’s reputation is that of a “free soil man,” opposing those who would seek to extend slavery geographically, while not calling for abolishing it entirely. As such he will vote five times in favor of Wilmot’s proviso during his term in office.

His first address to the House, on December 22, 1847, is very brief, but pointed. It becomes known as the “spot speech” and it lays out the case that American was intruding on Mexican land, and not vice versa, when the fighting began.

Lincoln’s second speech comes nine days after the House has passed a resolution by a vote of 85-81 saying that the war was “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States.” It paints a picture of a President who deceived the nation into starting a war to grab land belonging to Mexico, and is now “bewildered” about how to force the Mexicans into a treaty that makes it all look legal.

While the Whigs continue to hammer away at Polk over his motives for the war, the Democrats are desperately searching for a path to securing peace within their own party. They must arrive at an option to Wilmot’s total ban on the expansion of slavery into the west, which is anathema to their entire Southern wing. The house has repeatedly rejected their first choice – declaring that the 34’30” Missouri Compromise line be the boundary for Slave vs. Free State designation in all newly acquired land.

As a fallback, they turn to a new option, one will become known as “popular sovereignty.” On the surface the idea is simple and consistent with the original spirit of personal liberty in America – namely, that the people themselves should determine the rules by which they will be governed. This classical argument of the States’ Rights Democrats goes back to Jefferson, and is disputed by the Federalist conviction that local “sovereignty” is trumped by the majority will of the nation as a whole. On December 22, 1847, the “popular sovereignty” solution is floated out on the floor of the Senate by Senator Daniel Dickinson of New York.

The Democrats will spend the next decade trying to substitute “popular sovereignty” for the Wilmot Proviso as the right policy for resolving the conflicts over slavery in the west. In the end they will fail.

The Treaty Of Guadalupe Hidalgo Ends The War

With political pressures mounting on Polk, good news arrives from Mexico City saying that the controversial Nicholas Trist has achieved a breakthrough on a treaty with Manuel de la Pena y Pena, the ex-Supreme Court justice named interim president after Santa Anna’s resignation.

Unlike the strident Santa Anna, Pena y Pena is eager to resolve the conflict, assuming it allows Mexico to retain its standing as an independent nation. Trist knows that Polk supports this outcome, and so the talks, at the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo outside Mexico City, focus on drawing territorial boundaries in the north and agreeing on a cash payment. Trist walks a fine line with Polk’s instructions here. He agrees to a border that is slightly farther north than Polk wants, both in Arizona and in Alta (upper) California, while still insisting on control over the important port city of San Diego. At the same time he convinces the Mexicans to accept $15 million for the land, well under the $30 million Polk sets as a maximum.

On February 2, 1848, Trist and Pena y Pena sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and send it off hoping for final approval in Washington. Polk receives a copy on February 19, and finds the terms acceptable, despite his ongoing anger over Trist’s rogue methods. The next day, he forwards it to the Senate. As expected, the treaty becomes a political football, with both the Democrats and Whigs trying to stake out their positions on the war and the treaty in advance of the 1848 presidential race. On February 23, news that ex-President John Quincy Adams has died, following a sudden collapse on the floor of the House, momentarily mutes the contentiousness. After a hiatus to honor Adams, the Trist Treaty is finally approved in the Senate on March 10 by a vote of 38-14.

Mexico surrenders 529,000 square miles to America, or 55% of its original New Spain landmass.

This represents 18% of the total U.S. acreage and will eventually comprise the states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. With this, Polk achieves the goal of Manifest Destiny, extending and securing America’s borders from sea to shining sea.

But the victory comes with a “poison pill” that will haunt and divide the nation going forward: whether or not slavery will be allowed to take hold in the Mexican Cession land just acquired.

Important Battles of the Mexican War In 1847

| 1847 | Battle | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Feb 3-5 | Pueblo de Taos | US | 200 | Another victory in New Mexico |

| Feb 22-23 | Buena Vista | Draw | 4,200 | Ends Taylor’s successful campaign in the North |

| Mar 9-29 | Siege of Veracruz | US | 3,200 | 3000 captured in Scott’s amphibious assault |

| April 18 | Cerro Gordo | US | 4,450 | Santa Anna ambush foiled, 3000 more captured |

| Aug 20 | Contreras | US | 3,200 | Scott overcomes Santa Anna 3:1 edge in troops |

| Aug 20 | Cherubusco | US | 1,000 | Open the path toward Mexico City |

| Sept 8 | Molino del Rey | US | 2,250 | Two Generals lost and Mexicans reeling |

| Sept 12-13 | Chapultepec | US | 2,050 | Fall of military citadel spells doom for defenders |

| Sept 15 | Mexico City | US | ?? | Belen & San Cosme Gates fall; Santa Anna flees |