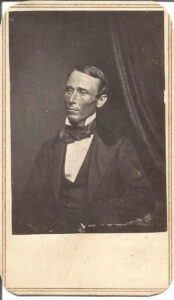

William Walker, American Filibusterer

The quest by Southerners to expand slavery outside of America’s existing borders is ongoing. It succeeds in 1836 with the founding of the Texas Republic on some 350,000 square miles of Mexican land. Then fails nine years later in Cuba when an invasion attempt backed by Mississippi Senator John Quitman, carried out by the Venezuelan “free-booter” (filibusterer), Narciso Lopez, ends with his execution in Havana.

Then comes the Mexican War which appears to open up new slavery land all the way from Missouri to California. That is until the 1846 “Wilmot Proviso” signals the intent of the North to oppose expansion – a move which panics the South and draws it toward secession.

Into this context comes the larger-than-life figure of William Walker who intends to lead the Southern cause. Outwardly he presents a frail almost feminine stature and a quiet manner of speaking. But underneath lie the “cold grey eyes” and explosive temper of a repeated duelist, and the unshakeable egomania of one destined to be “no ordinary person.”

Walker is born in Nashville in 1824, earns an MD degree from the University of Pennsylvania at 19, then practices briefly before moving to New Orleans, where he passes the bar and takes up journalism, as editor of the New Orleans Daily Crescent. The gold rush brings him to California and works at the San Francisco Herald. At age twenty-five he has become a physician, a lawyer, and a journalist, a full life for most men, but not for Walker.

In 1852, he sets his sights on leading a small army to conquer, and then personally rule, land to the south, reinstituting slavery as he goes.

His first move is against the Mexican province of Sonora located below the border with Tucson.

He set sail in October 1853, along with a small band of only 45 soldiers, down the Gulf of California before making landfall and marching 100 miles inland to seize the capital of La Paz.

While he proclaims his role as a dictator, his tenure is brief. Fighting with Mexican troops in November forces him to retreat from La Paz to Ensenada, near the California border in December. Despite the setback, he declares himself emperor of “The Republic of Lower California” (Sonora and the Baja peninsula) and leads another expedition south. But this too ends in failure, and on May 8, 1854, Walker and 34 stragglers are taken into custody by U.S. authorities at Tia Juana and charged with violating the 1794 Neutrality Act.

Still, he is undeterred, and within a year turns to Nicaragua for his next conquest. It is a small nation, with some 260,000 residents dominated by Mestizos (Indian/Spanish blood) and with a history of civil wars which leave it vulnerable to invasion.

Walker is backed this time by Democrats like Pierre Soule, Senator Lewis Cass, and General John Wool, and by financier George Law who envisions a railroad running across Nicaragua to link the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific. Manpower is added by recruiting mercenaries such as Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of combat in Spain and Hungary.

After a 3500-mile sea voyage, Walker lands with sixty troops at the port of Realejo on June 16, 1855. He is greeted by President Castellon who sees him as an ally in the internal struggles for power. Walker feigns support for Castellon, wins a pivotal battle at Grenada on October 13, then executes two government officials and sets himself as head of the army and de facto ruler. He further legitimizes his status by sending the Grenada Curate, Father Vijil, to Washington, where President Franklin Pierce reluctantly acknowledges Walker’s coup.

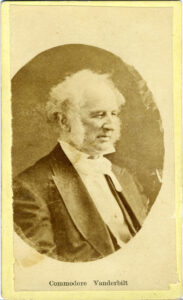

Once in control, it becomes clear that his agenda is not to reform Nicaragua, but to “Americanize it.” He reinstates the practice of slavery, declares English the official language, introduces a new currency, and aggressively seeks US immigrants. At the same time, he makes a fatal blunder by assuming control over the assets of the “American Transit Company,” owned by the New York tycoon, Cornelius Vanderbilt. The Commodore already has a thriving business transporting cargo from east to west across Nicaragua and sees the possibility of a canal. Upon hearing of Walker’s interference, Vanderbilt cables him:

I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I will ruin you.

He does so by convincing the leaders of countries bordering Nicaragua that Walker intends to invade and take them over. The pushback begins with Costa Rica but soon includes Honduras, Salvador, and Guatemala. In typical fashion, Walker plunges ahead to meet them, sending his French and German mercenary units across the southern border into Costa Rica. They are, however, routed there on March 20, 1856, at the battle of Santa Rosa, with 59 men killed in action. More military losses follow at San Jacinto in September and Grenada in December, after which Walker burns his own prior capital in spite.

The town of Rivas becomes his last bastion in 1857, but by March his troops are eating their mules to avoid starvation. Capitulation arrives on May 1 when Walker and his remaining 463 troops are herded onto the USS St. Mary and returned to San Francisco.

Once there, however, he is greeted by cheering supporters and blames his latest defeat on a lack of support from the American government. In November 1857 he heads back to Nicaragua with 270 followers but is quickly arrested by Commodore Hiram Paulding.

After again being acquitted of violating the 1818 Neutrality Act, he conjures up his final mission to “Americanize the Five Nations of Central America.”

In the Fall of 1860, he is back at sea with a shipload of raiders, intent on storming into Honduras. This move is thwarted by a British Royal Navy ship which, instead of returning Walker to the United States, hands him over to the Hondurans. His protest – “I am the President of Nicaragua” – is ignored, and on September 12, 1860, William Walker, age thirty-six, is marched into the plaza at the city of Truxillo, tied to a chair, and shot dead by a firing squad of barefoot soldiers.

Thus ends the amazing adventures of “Colonel Walker, the grey-eyed man of destiny.”