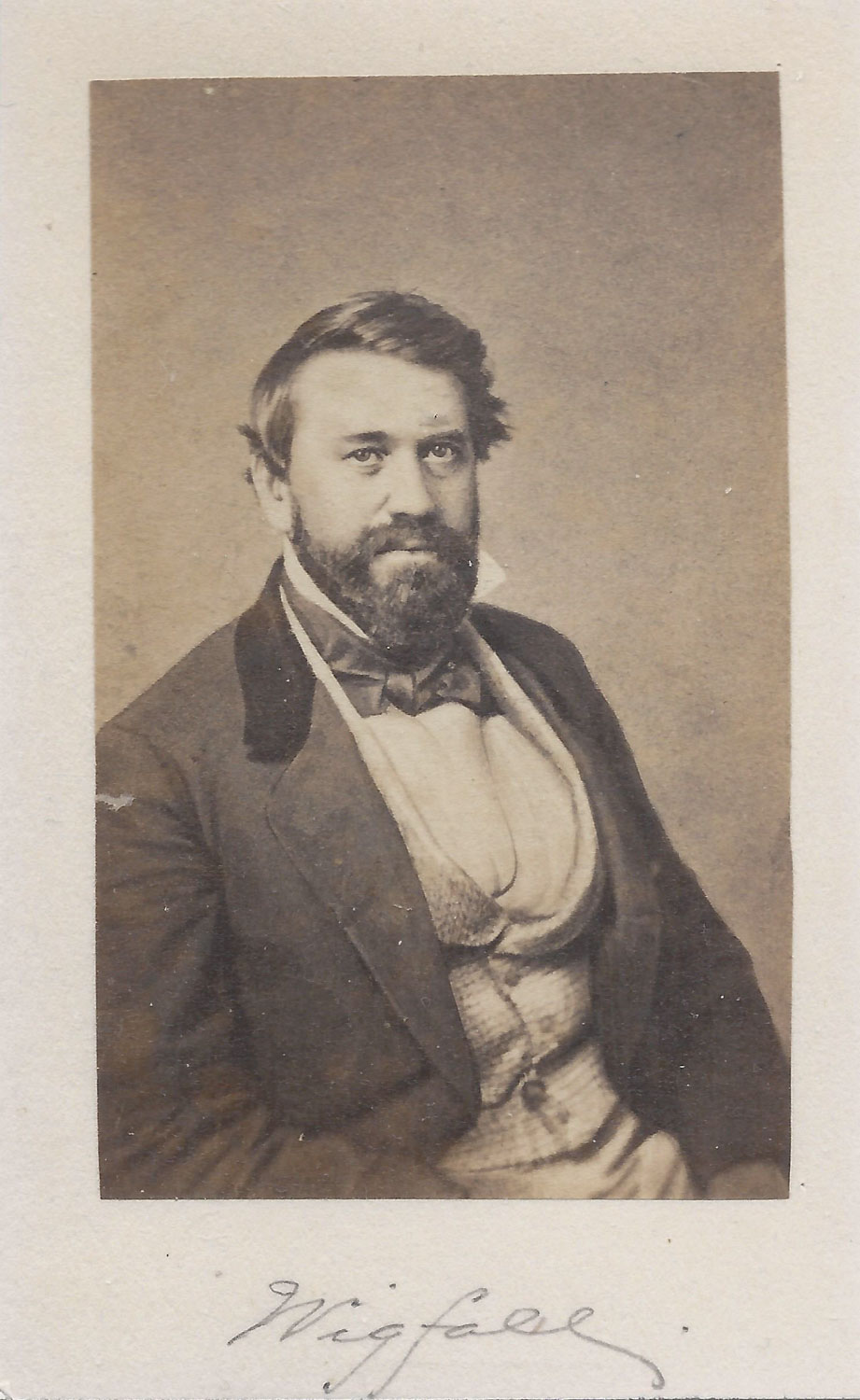

Louis T. Wigfall

Louis Wigfall’s future is shaped by his origins. On his mother Eliza’s side he is descended from the Trezevant family, long among the South Carolina elites. Her husband, Levi Durand Wigfall, is a prominent merchant in Charleston with a plantation in Edgefield, where Louis is born in 1816. He is surrounded by wealth and the conservative traditions of the South, from the Episcopalian Church to the old world codes of social grace, chivalry and dueling.

Tragedy, however, strikes early with the loss of both his parents – his father dying when he is two and his mother when he is thirteen. His care falls to his guardian, Allen Addison, who tutors him at home before sending him briefly to a military academy, then the University of Virginia, and finally the University of South Carolina in 1835. Two of his earliest influences there are President Thomas Cooper, an outspoken states’ rights advocate, and his successor, Robert Barnwell, a proponent of “nullifying” the federal tariffs on cotton.

From the beginning Wigfall stretches the bounds of acceptable campus behavior. He drinks and gambles to excess at local taverns, plays schoolboy pranks, writes endless petitions protesting college policies, and earns his reputation as an “insurrectionist.” But he is also intellectually keen and a gifted orator, traits that will serve him well in later years.

The decade following his graduation (1836-46) ends in disaster for him. After struggling to pass the bar, he dabbles in a law practice with his older brother in Edgefield, joins the 7th South Carolina Militia as Colonel, and begins delivering public addresses on patriotism. The satisfaction he experience between the military and the speech-making convinces him that his future lies in the exciting political arena rather than the tame world of law.

What Wigfall quickly encounters, however, is a raw battle for power being fought out between a select few South Carolina families. His first dose comes with the 1840 race for Governor, pitting John Richardson, uncle of Wigfall’s classmate and best friend, John Manning, against John Henry Hammond who is backed by another classmate, Preston Brooks and his influential family. The campaign is soon marked by intense personal animosity that leads Wigfall to call for a duel with Brooks. But before it can take place, Brook’s nephew, Thomas Bird, fires a shot at Wigfall on November 4, before being mortally wounded in return.

Two formal duels follow. The first pairs Wigfall against Brooks’ uncle, J.P. Carroll, where both men fire but miss, before agreeing to resign. Then comes the main match on November 12, 1840, with initial misses by both men followed by second shots that strike home. Wigfall is wounded in the thigh and Preston in the hip which leaves him with a permanent limp and the need for a cane (which he will later use to attack Senator Charles Sumner in 1856!).

Wigfall suffers in the aftermath of the violence. His social standing is weakened along with his law practice. The loss of income, combined with his own profligacy and medical bills for a dying son, leaves him unable to cover his debts, even after liquidating the remainder of his and his wife’s inheritances. He struggles to advance his political career as a delegate to the state Democrat convention as the 1844 elections approach, but his demand for immediate secession is rejected as too extreme.

With his reputation in South Carolina broken, he picks up his family in 1846 and moves to Texas. His cousin and former SC Governor, James Hamilton, is there and lines him up to join attorney William Ochiltree’s practice in Nacogdoches. The move changes his life and prospects going forward. He finally focuses on the law, and soon enough is sought after for his trial skills.

Wigfall’s arrival follows the 1845 Texas Annexation which turns into the 1846-7 Mexican War and the famous “Wilmot Proviso” in Congress, calling for a ban on slavery in the ceded southwestern territories. This plays right into his hostility toward the North, and he uses it to help establish the Democrat Party in the Lone Star state. He also reaches out to Senator John C. Calhoun and enlists in his movement for the South to leave the Union.

But his advocacy is met by U.S. Senator Sam Houston, the hero of the Texas Republic and a leading member of those Democrats who favor moderation and compromise. The 1857 race for Governor brings Wigfall, serving in the Texas State Senate, head-on against Houston. He throws his support behind Hardin Runnels, a states’ rights man and a secessionist like himself. When Runnels scores a surprising win, much of the credit goes to Wigfall whose prowess as a stump speaker is said by observers to rival Houston.

Two years later, Texas Senator Henderson dies in office and the State Legislature sends Wigfall to Washington to fill out his term. He is sworn in on March 5, 1859, joining other Southern Fire-eaters such as Robert Rhett (SC), William Yancey (Ala), Edwin Ruffin (Va), and Henry Benning (Ga). At first they are unable to carry the day for disunion, but this roadblock ends after John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry on October 16-18, 1859 and the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860. Wigfall coauthors the December 13, 1860 “Southern Manifesto,” declaring that any hope for relief in the Union was gone and that the honor and independence of the South required the organization of a new Confederacy.

He remains in the Senate until March 23, 1861 when he becomes the 21st southern Senator to withdraw or resign from office. In the interim he gathers intelligence on Union plans for the coming war and helps recruit troops in Maryland to send to the South.

The Confederacy is formally organized on February 8, before his exit, and with President Jefferson Davis’s support he becomes a member of the Provisional Congress and an aide to General Pierre Beauregard commander of CSA troops at Charleston. His presence there leads to an overtly showboating move for public attention. After a two day bombardment of Ft. Sumter has worn down the Union defenders, Wigfall commandeers a small rowboat, arrives at the fort with a white flag tied to his sword, and offers surrender terms to the astonished Colonel Robert Anderson. While his act infuriates Beauregard, the public deems Wigfall an overnight hero.

As the actual war breaks out, Davis appoints him Colonel of the First Texas Infantry on August 28, 1861 and then Brigadier General of the Texas Brigade on December 13 of that year. But

Wigfall’s only appearance in the field is during the June 1862 Peninsula Campaign where he is assigned hospital duty to care for those wounded.

The remainder of the war years are devoted to his role as Texas Senator in the CSA Congress where he is regarded as a ferocious supporter of the military and his favorite generals, notably Joseph Johnston. Of particular note, are his legislative successes at initiating Conscription and then extending its age requirements and funding much needed railroad construction.

But Wigfall’s best efforts in Congress are more than offset by his campaign to undermine Jefferson Davis. The two begin as friends in 1861, but petty rivalries between their wives cause an early strain, followed by heated disagreements over battlefield strategies and field commanders. After Gettysburg and western defeats, Wigfall attacks Robert E. Lee, John Pemberton and Braxton Bragg. In January 1865 his successor as head of the Texas Brigade, the heroic John Bell Hood, is relieved of command after a loss at Franklin. The influential Wigfall announces that Davis’ “pig-headedness and perverseness” are destroying the South.

As the tide turns further against the South, Wigfall opposes the critically important enlistment of black soldiers, arguing that he doesn’t want to “make a Santo Domingo of his country.” His racial prejudices remain unchanged from his early days:

I wish to live in no country where the man who blacks my boots or curries my horse is my equal.

Wigfall does support Lee’s appointment to head the Army on February 6, 1865, but by then it is too late, and the surrender at Appomattox occurs on April 9, 1865. A distraught Wigfall decides to flee west where he hides out until departing for England in 1866, after which his family joins him. They prosper at first, but by 1869 he is again broke and living off of odd jobs. While his contacts with fellow Southerners remain bleak, he decides to return to the States in 1872. He stays in Baltimore with his family before moving to Galveston, Texas, dying there at fifty-seven.

In the end, Wigfall’s many talents are offset by his inbred arrogance, his drinking and financial carelessness, his racial prejudices, and the personal vendettas that that extend from his early duels to his latter efforts to undermine those who oppose him, most notably Jefferson Davis.

Very fair analysis of Wigfall. He is the Gr Gr Grandfather of my wife. We have most of Wigfall’s personal papers and copies of those held in the Library of Congress. We have the surrender flag you speak of from Sumter, it happens to be his handkerchief. Thank you for putting a fair biography of Wigfall out there.