The Real Day the Declaration was Signed

You are there: Despite some residual controversy, most historians believe that while agreement on the content of the Declaration occurs on July 4, the official day the declaration was signed is delayed until August 2, 1776.

This conclusion is based on two facts. The first is that New York State doesn’t signal its approval until July 19; and the second, is the significant time that’s required to complete the complex process of “engrossing” the final document.

This preparation task falls to one Timothy Matlock, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, known for his excellent penmanship. He is charged with “engrossing” (handwriting) the 320 words of the Declaration on what turns out to be four 30×24” pages of highly durable parchment, most likely made from sheepskin. (The result can be seen to this day at the National Archives in DC.)

So what then actually takes place on July 4?

We know that the final language of the Declaration is completed on the 4th. The initial draft is written over 17 days by Thomas Jefferson, who is considered the leading wordsmith in the hall. But his work is then shortened and heavily edited by the four other members of the select Committee of Five (Ben Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston).

One example of the many edits involves the famous words in the second paragraph:

| Jefferson’s Original Version We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights, inherent & unalienable, that among which are the preservation of life & liberty and the pursuit of happiness. | Final Version We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. |

The Declaration is thus the work of the Committee and of the delegates as a whole.

On July 4 a formal vote on the text is taken, with each state casting one ballot. Nine signal their approval; two others, Pennsylvania and South Carolina, vote “no;” New York abstains; and Delaware remains evenly split. But with the majority clearly in favor, the Declaration is adopted.

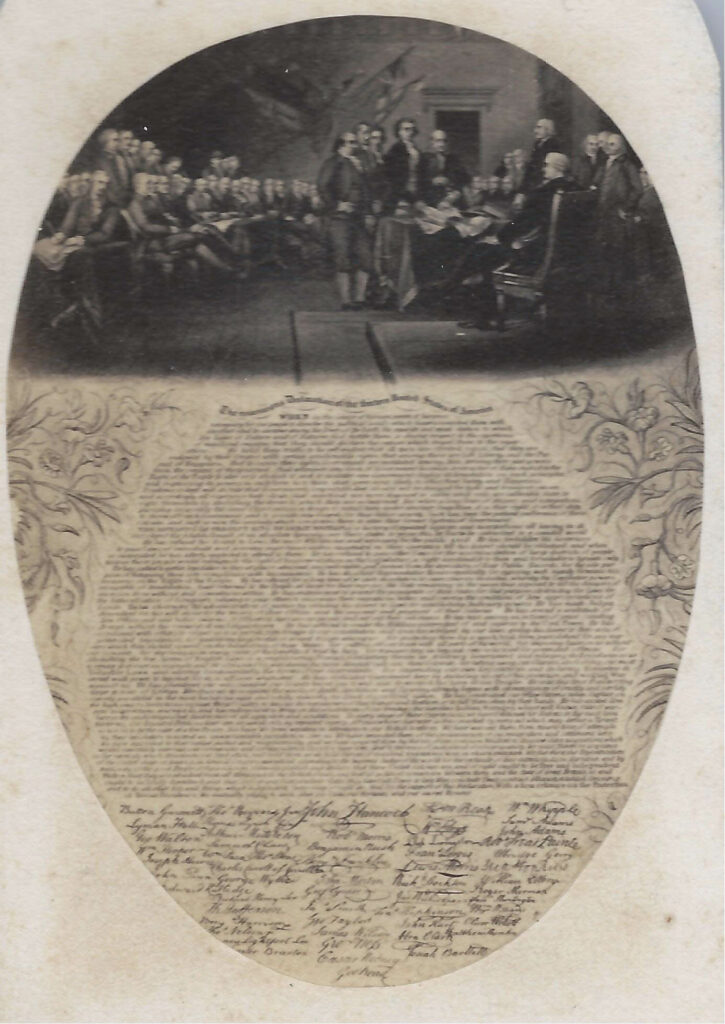

What happens next is unclear. For certain two men immediately add their signatures: John Hancock as President of the Convention and Charles Thomson as Secretary. It is then handed over to a Philadelphia printer, John Dunlop, who typesets some 200 copies into a traditional Broadside format which includes the two names. On July 5 citizens wake up to see these startling bulletins posted around the city.

Charles Thomson’s role in this history is often overlooked, but he alone is charged with recording the day-by-day convention events, not only on July 4 but over the entire fifteen-year lifespan of the Continental Congress (1775-81) and the Congress of the Confederation (1781-9).

The public doesn’t get to see the actual behind-the-scenes details until 1821 when the Secret Journals of the Acts and Proceedings of Congress are finally published. The records say nothing about signings on July 4, but due include a cite for August 2, 1776:

The declaration of Independence being engrossed & compared at the table

was signed by the Members.

In the end, a total of 58 signatures from across the thirteen colonies appear on the engrossed document:

Number of Signatories to the Declaration By State In August

| State | NH | Mass | RI | Conn | NY | NJ | Pa | Del | Md | Va | NC | SC | Ga |

| # | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

But many of the Founding Fathers do not have a chance to sign the Declaration. That’s because by August 1776, fighting in the Revolutionary War, which has already gone on for 15 months, is intensifying, and they are committed elsewhere. One is George Washington, Commander of the Continental Army, who is in Manhattan at the time preparing his defenses for the coming British assault. Other key figures who are away include Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, James Monroe, Patrick Henry and Robert Morris.

When the time arrives for the August ceremony, gallows humor is said to prevail since each man knows they are signing a death warrant for treason against the Crown. Ben Franklin sums this up best in his famous observation: “Now we must indeed all hang together or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”