Webster Hayne Debate on the Value of the Union

From January 19-30, 1830, two U.S. Senators engage in a series of debates that culminate in what historians often consider the most moving oratory ever delivered in the halls of Congress, the Webster Hayne Debate on the Value of the Union.

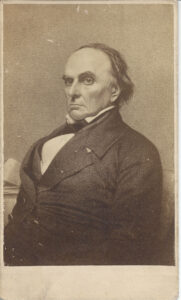

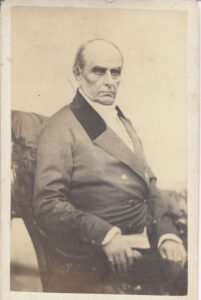

On one side is Robert Hayne of South Carolina, 39 years old, owner of almost 200 enslaved persons on his three plantations, and fiery supporter of “nullifying” existing tariffs on cotton. On the other is 48 year old Daniel Webster of New Hampshire, America’s most famous attorney at the time, who will eventually try over 200 cases before the Supreme Court. “Black Dan” favors the cotton tariffs which “protect” New England’s textile manufacturers from having their pricing undercut by competitors in Britain.

At first the two debate the tariff question, until Hayne ups the ante on January 25 by asserting that the North has usurped power over the federal government and is intent on ruining the Southern economy – moves which threaten the preservation of the Union.

In all the efforts that have been made by South Carolina… she has kept steadily in view the preservation of the Union, by … resistance against usurpation. The measures of the Federal Government have… prostrated her interests, and will soon involve the whole South in irretrievable ruin. …

The following day, Webster responds with his oratorical masterpiece known as the “Second Reply to Hayne.” As with many of his speeches, he begins by dialing down traces of hostility.

When the honorable member rose, in his first speech…nothing was farther from my

intention than to commence any personal warfare.

He then reframes the central issue in the debate. In his judgment it goes beyond Hayne’s objection to the tariffs or even his impassioned defense of slavery to a more fundamental question: “what is the value of the Union to all of the citizens?”

In one final five-minute burst he answers his own question. First by asserting the glorious future ahead as long as the center holds…

While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out

before us, for us and our children.

Then by painting a bleak picture of what would follow a schism…

When my eyes shall be turned to behold, for the last time, the sun in Heaven,

may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once

glorious Union; on states dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent

with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood!

Finally by closing with an emotional appeal to all on behalf of the Union…

Let their last feeble and lingering glance, rather behold the gorgeous Ensign of

the Republic… not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured —

bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as, what is all this worth?

Nor those other words of delusion and folly, liberty first, and union afterwards

—but…that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart—liberty and

union, now and forever, one and inseparable!

While Webster’s close is greeted with applause, Hayne is unmoved. His final volley is delivered on January 27.

The gentleman has made an eloquent appeal to our hearts in favor of union…(but)

Sir it is because South Carolina loves the Union, and would preserve it forever, that

she is opposing now, while there is hope, those usurpations of the Federal Government,

which, once established, will, sooner or later, tear this Union into fragments. …

And there, for the moment, the impasse ends. The Webster Hayne Debate will undoubtably be always remembered as a moving one.

For more on the Webster Hayne Debate

See Chapter 32