Section #11 - Other Military Conflicts

World War II: September 1, 1939 – September 2, 1945

The crippling peace terms imposed on Germany at Versailles after World War I set the stage for the emergence of Adolph Hitler and the Nazi Party and World War II.

While born under a cloud of illegitimacy in Austria, Hitler leaves home and volunteers in 1914, serving in the Bavarian Army throughout the war. His duty as a Lance Corporal involves dangerous runs across the trenches to deliver battle orders. He receives a First and Second Iron Cross for bravery, suffers a shrapnel wound, and is in hospital due to a poison gas attack when the war ends. The capitulation shocks him and he embraces the “stab in the back” betrayal theory that Jewish bankers cost Germany the war. From then on Hitler dedicates his future to restoring national power, taking revenge for its losses, and wiping out the entire Jewish population across Europe.

Chaos marks attempts to govern Germany in 1918. The country is strapped by war reparation debts and the presence of foreign troops on her soil to insure that payments are made on time. The Weimar Republic is ostensibly in control, but plagued by threats from communists and anarchists and those wishing to restore the monarchy. This political turmoil leads to the emergence of the far right German Worker’s Party around 1920. Hitler joins on January 1 of that year and quickly rises up the ranks.

In April 1920, he proposes a name change to the National Socialist German Workers Party, abbreviated as Nazi’s. Its promise, especially to the working classes, is to put down the communist threats, restore law and order, stop run-away inflation and rebuild Germany’s economy, military and national pride.

In 1924 Hitler attempts a coup against Weimar – the Munich “Beer Hall Putsch” – with help from none other than Eric Ludendorff. But it fails and Hitler lands in prison for roughly a year during which time he outlines his core beliefs and plans for Germany in his book, Mein Kampf. After his release, he spends the next decade rising to power. He does so by combining the political bullying tactics of his Brown Shirts under Ernst Roehm (whom he later kills) with a clever campaign to win approval from the popular German President Paul von Hindenburg. On January 30, 1933, the old general, who dislikes Hitler personally, nevertheless appoints him Chancellor.

This is followed by a mysterious fire at the Reichstag on February 27 that finds Hindenburg agreeing with Hitler to crack down on suspected traitors, particularly the communists. The so-called Enabling Act passed by the Reichstag on March 23, 1934, essentially hands dictatorial powers over to Hitler. Then on August 2 Hindenburg dies and Hitler succeeds him as President. On August 19 of that year a national plebiscite is held with 90% of the voters supporting Hitler as Fuhrer and Chancellor combined. He is now free to work his will on the fatherland.

Hitler begins by rebuilding Germany’s infrastructure and economy and succeeds during his early tenure. But that effort is hardly sufficient for him. His personal philosophy is shaped by the Social Darwinist thinking of the Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg. It rejects all traditional religious teachings and admonitions in favor of a “survival of the fittest” mandate applied to nations. Hence in Hitler’s mind it becomes the “duty” of Germany to devour its neighbors or eventually be justifiably destroyed by them. Within this godless context he sets out to conquer the world.

He finds an ally to this scheme in Italy, where Benito Mussolini conjures a return of the Roman Empire and creates a fascist regime to work his will. In 1936 he aligns with the militarist faction in Japan seeking dominance in the Pacific Rim by signing the Anti-Comintern Pact. This combination of Germany, Italy and Japan becomes the “Axis Powers,” supposedly dedicated to opposing the communists, but actually preparing for colonial expansion.

The Axis begins to act in 1935 with Italy invading and occupying Ethiopia. In 1937 Japan seizes Manchuria, with all of China in its sights. In 1938 Hitler starts his drive to broaden Germany’s borders under the call for “lebensraum” (living space). His first move involves the peaceful annexation of Austria. He next convinces Britain’s naïve Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that if only the Czechs were to surrender their Sudetenland, the world would enjoy “peace in our time.” The Munich Agreement of 1939 signed by Britain and France insures this tragedy.

But of course “appeasement” only provokes Hitler to step up his demands and prepare for his next move east into Poland. Before acting he executes a diplomatic tour de force by signing a Non-Aggression Pact with Russia on August 23, 1939. The agreement, which shocks the west, includes secret codicils by which Russia will invade Poland from the west when war breaks out.

It does so on September 1, 1939, preceded by a phony effort to convince the world that Poland initiated the conflict. As guarantors of Polish sovereignty, Britain and France issue an ultimatum to Hitler to abandon the territory gained. On September 3, the time limit passes and the disillusioned French and British declare war on Germany.

Still uncertainty reigns in Paris and London, where few statesman fully understand the German threat. As First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill is one of them, and he assembles a British Expeditionary force of nearly 400,000 men and ships them across the Channel beginning on September 9, 1939. In France, Prime Minister Edouard Daladier also properly reads Hitler’s intentions but his efforts are frustrated by a still traumatized public and military who dread the prospect of another war with Germany.

Up to the Polish incursion, Hitler has proceeded in large part on bluff and bravado, since his military is not yet fully prepared to fight on a large scale. But neither are the Allies, and so the period from September 1939 and April 1940 becomes known as the “Phony War.” During this period of inaction, the Allies dawdle while Hitler massively upgrades his military capacity and pushes his often reluctant general staff to prepare for the real fighting ahead.

In France, Daladier gives way to Paul Reynaud on March 21, 1940, and on May 10, Winston Churchill replaces Chamberlain, already dying from cancer, as Prime Minister.

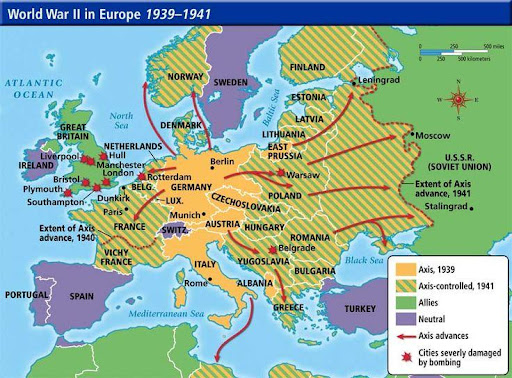

May 10 also marks Hitler’s move against France in a two-pronged attack. In the north, Belgium territory is breeched along the same lines as the 1914 Schlieffen Plan. To the south, the Germans move through the Ardennes toward Sedan, aiming at Paris. The whole world watches in wonder as Germany’s “blitzkrieg” campaign plays out. In the air, Germany’s Ju 87 “Stuka” dive bombers level city after city. On the ground, Panzer tanks elude the fixed concrete bunkers of the Maginot Line and race across land, maneuvering in ways unheard of during the 1914-18 years of trench warfare.

On May 15, 1940, Reynaud contacts Churchill with a shocking message: “we have been defeated.” Churchill immediately flies to Paris where he asks General Maurice Gamelan when he intends to begin the counter-offensive. Gamelan simply shrugs, relying that he has no reserves left to continue the fight.

The sudden collapse of France forces intense debate within Churchill’s War Cabinet about how to proceed. The influential Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, lobbies on behalf of a peace treaty with Hitler and the safe return of the expeditionary troops stationed around Calais. In the midst of the infighting, Hitler’s Deputy Fuehrer, Rudolph Hess, takes it upon himself to fly a secret mission to Scotland, evidently to rally the right-wing faction led by Sir Oswald Mosely toward signing a peace treaty. But nothing comes of this and Hitler denounces Hess who ends in jail.

Churchill refuses all concessions to Hitler, and the British are left standing alone, buoyed only by his will power and stirring rhetoric: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

The PM’s most immediate challenge is now the evacuation of his surrounded army at Dunkirk, and between May 26 and June 4 he extracts all but 40,000 by sending small boats, often civilian, across the Channel to bring them home. While some historians argue that Hitler allows the escape to secure a peace treaty, his actions enable Britain to stay in the fight.

With Poland, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria already in his pocket, Hitler next pounces on Scandinavia, and by June 9, 1940 Finland, Denmark and Norway are all subdued. On June 10, Germany invades North Africa, beginning the famous three year back and forth conflict between Germany’s Erwin Rommel and Britain’s Bernard Montgomery. It will end with a British victory in the Second battle of El Alamein in November 1942.

On June 22, 1940, Hitler further humiliates the French by forcing them to sign an Armistice Treaty in the same train car at Compiegne where the Germans capitulated in 1918. From then until the liberation in August 1944, occupied France will be under the Vichy government headed by World War I hero Philippe Petain. After the war, Petain is sentenced to death for treason, but his advanced age leads to a commutation.

Absent a peace treaty, the Battle of Britain is well under way by July 1940. Over a four month period, the Royal Air Force heroically battles Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe to a stand-off. Churchill remarks: “never have so few done so much for so many.” This failure to gain air supremacy effectively ends Hitler’s plan to invade Britain.

In June 1941, a frustrated Hitler redirects his army toward the primary objective he has had all along: the conquest of Russia. For him, the Slavs are an inferior race and incapable of further survival. Despite warnings from his military staff, Hitler proceeds with “Operation Barbarossa.” Soon enough he will learn, like Napoleon, that he is not only facing the unlimited manpower of the Red Army, but also the Russian winter.

A second major turning point in World War II occurs in the Pacific theater on December 7, 1941, when Japan carries off its surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Station at Pearl Harbor. The strike is in response to President Franklin Roosevelt’s effort to cut off the supply of oil to Japan in order to quell its ongoing aggression in the region. Despite warnings from Naval Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, a former student at Harvard, the hard-liners in Tokyo, led by Army Commander Hideki Tojo, insist on the attack. Due to communications difficulties between Tokyo and Washington, the bombardment begins before Ambassador Nomura can deliver a formal declaration of war to Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

While America’s carrier force is away from Pearl, the results are devastating to the U.S. Navy. Nineteen ships are lost along with 400 aircraft and some 2400 servicemen. The following day, Congress declares war on Japan after Roosevelt’s opening line: “December 7, 1941. A date that shall live in infamy.” America’s entry quickly results in the transfer of its much needed surplus supplies to Britain and its other partners.

On December 11, 1941, Hitler makes a second strategic blunder that will rival his move against Russia. Addressing the Reichstag with his usual fiery megalomaniac bravado, he declares that Germany is now at war with the United States. Taken together Operation Barbarossa and the response to Pearl Harbor will prove fatal to Adolph Hitler.

On January 20, 1942 Gestapo Chief Reinhard Heydrich, “the man with the iron heart” according to Hitler, assembles a meeting of 15 top security officials, including Adolph Eichmann, at the Wannsee Mansion to announce a “final solution” to rid the German empire of all Jews. This converts concentration camps such as Dachau and Auschwitz into industrial-sized killing factories where upwards of six million Jews and other undesirables are tortured, gassed to death and cremated. Heydrich will be mortally wounded by Czech agents in Prague in May 1942. Eichmann will be captured by Israeli agents in May 1960 after hiding in Argentina, and executed after a trial in 1962.

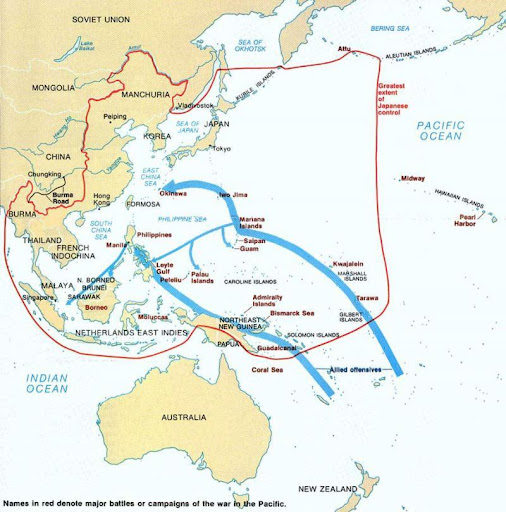

In the Pacific theater, a raid in April 1942 on Tokyo by Captain Jimmy Doolittle raises American spirits after Pearl Harbor. Then on June 7, 1942, the tide of naval warfare swings toward the U.S. at the Battle of Midway. Under Admiral Chester Nimitz, US torpedo planes manage to sink four Japanese carriers in a victory many compare to Trafalgar. This sets the stage for America’s army corps under General Douglas McArthur to join the navy in its “island hopping” campaign between 1942 and 1945 to reverse Japan’s earlier successes and finally win the Pacific war.

Meanwhile Hitler’s Russian invasion actually begins well, as Joseph Stalin’s troops retreating east toward Moscow following a “scorched earth” strategy. But as the summer of 1942 turns to winter, conditions for the German army begin to deteriorate. This leads to the decisive battle of World War II. It begins on August 22, 1942 and takes place in front of Stalingrad, some 600 miles south of Moscow. Gradually the German Sixth Army is nearly surrounded by the Russians and General von Paulus pleads with Hitler to retreat. Instead he is ordered to stay put which he does until February 2, 1943 when his food and ammunition run out, and he surrenders. The losses on both sides at Stalingrad are staggering: the German estimate runs from 750-850,000; for the Russians it is 1.1million.

From Stalingrad forward, Germany will be fighting a war of defense, not offense.

Throughout 1943 Joseph Stalin steps up pressure on Churchill and Roosevelt to open a second front in Europe to lessen the Russian bloodshed and facilitate his offense against the Reich.

All he gets, however, is the invasion of Italy which begins in Sicily on July 9, 1943 with Generals George Patton and Bernard Montgomery racing to conquer the territory. In response, on July 25, the Italian Grand Council removes Mussolini from power, and he remains under arrest until September 12, when the German raider, Otto Skorzeny, rescues him. But Hitler sees a broken man after the Duce arrives in Berlin and knows that the future defense of Italy will fall to the Germans.

It is not until June 6, 1944 that Stalin gets the second front he has demanded. It is called “Operation Overlord” and becomes the largest amphibious assault in history. Allied preparations are obvious to spies in England, but the exact date and location remain secret.

The Germans assume that the landing will take place in the Pas de Calais, the shortest (50 mile) passage from Britain to France. Instead, the Supreme Commander of the operation, General Dwight Eisenhower, opts for the beaches of Normandy (“Utah, Sword, Juno”) where the Reich fortifications are much lighter. The surprise landing is a success, helped along by Hitler’s refusal to release his tank reserves in time, believing that Normandy is simply a feint.

From Normandy onward, the noose around Germany progressively tightens, with the Overlord troops heading east across France (liberated in August 1944) and Belgium, and the Russians rapidly heading west behind its superb Field Marshal Georgy Zhukov.

On January 27, the Red Army comes upon the extermination camp in Poland at Auschwitz and the world sees the horrors wrought by Hitler and the German people against the Jews. Allied Air raids executed by the unforgiving Sir Arthur Harris go unopposed and devastate German cities, the most notable being the Dresden fire-bombing on February 13, 1945.

Occupation of Berlin now becomes the prize and Eisenhower, apparently out of respect for the Russian losses over time, allows the Red Army to enter the city first on April 16. (Many historians argue that his decision to back away from Berlin increases Stalin’s ability to consolidate territorial gains to the east and create his “iron curtain” hegemony, prompting the post-1945 “Cold War.”)

Two weeks later, on April 30, Adolph Hitler and his just named bride, Eva Braun, commit suicide inside of the Fuhrer-bunker. Their bodies are burned, but the bones are recovered by the Russians who send them to Stalin in Moscow.

Some senior Nazi officials like Joseph Goebbels chooses to die alongside Hitler, while others make desperate attempts to leave the capital. Herman Goering, Heinrich Himmler and other Nazi perpetrators will eventually be captured, tried as war criminals at Nuremberg, and die there either by swallowing cyanide tablets or by hanging.

Mussolini and his mistress meet their end on April 28, 1945 when they are shot by Italian partisans and their bodies are strung upside down in a nearby town square.

VE Day (Victory in Europe) is celebrated on May 8, 1945 after a final peace treaty is signed by Admiral Karl Doenitz, mastermind of Germany’s submarine warfare and Hitler’s chosen successor as President. Doenitz will be tried at Nuremberg and sentenced to ten years in jail.

While the European conflict is coming to an end, so too is the war in the Pacific.

The combined naval, air and infantry power of America and the British Empire reverse the Japanese gains from the start of the war one by one, starting with victory at Guadalcanal in February 1943. Saipan falls in August 1944 and General MacArthur keeps his promise to return to the Philippines, landing at Leyte in October of that year. The vicious fighting for the island of Iwo Jimi ends in February 1945, followed by the bitter seizure of Okinawa in June 1945.

Despite these setbacks, the Bushido code of obedience to the Emperor demands that Japanese soldiers and civilians fight to the death. Calls for surrender are rejected, and on August 6, 1945 an American B-29 Superfortress christened the Enola Gay drops a 15,000 ton uranium bomb on the city of Hiroshima, leveling the entire city in minutes. Still Hirohito refuses to capitulate, and three days later a 10,800 ton plutonium bomb destroys five square miles in the city of Nagasaki.

Soon thereafter both the entire Philippine Islands and the British bastion of Singapore are back in Allied hands.

But the horrors suffered by the Japanese civilians during and subsequent to the two atomic attacks finally convince the Emperor and his military advisors to give up — and a peace treaty is signed aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945.

General MacArthur is placed in command over the Japan nation after the peace, charged with restoring civilian control and ending its militaristic culture. While attempts are made to paint Hirohito as a passive pawn of his generals throughout the war, MacArthur rightly rejects that idea. But when the Tokyo War Crimes trials commence, he decides to leave the Emperor alone to serve as a figurehead symbol of reconciliation. That leaves seven senior men, including Tojo, face justice and be sentenced to death by hanging.

Estimates of the total number of military and civilian casualties in World War II range for 35 million to 60 million. This compares with the 37 million approximated in World War I. By far the greatest number of combat deaths in the second conflict belong to Russia and Germany.

Military Deaths Among The Axis and Allied Powers in WWII

| Russia | Germany | Japan | U.S. | Italy | Britain | France |

| 9,800 | 5,533 | 2,120 | 417 | 301 | 383 | 217 |

In retrospect, perhaps the lessons of the World Wars are best summed up in the words of the philosopher George Satayana: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”