Section #3 - The War of 1812

The War of 1812: 1812-15

Lead-up To The War of 1812

The Revolutionary War ends with an American victory in 1781, but does not eliminate the military threats to the new nation. Britain remains to the north in Canada and New Spain to the west. Also France’s crucial support for the Americans in the Revolutionary War further alienates the British. Then in 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte becomes First Consul in France and signals his intent to restore the quest for global hegemony.

While George Washington has warned against entanglements in foreign conflicts, from 1797 onward America is caught between France and Britain. President John Adams is first to feel the squeeze when the French Prime Minister Talleyrand demands a $12 million ransom payment from the U.S. in what becomes known as the “YYZ Affair.” America’s ambassadors refuse to pay and some Federalists encourage Adams to declare war on France. Instead the 1778 Treaty of Alliance is discarded and the French respond with naval attacks, most notably off St. Kits in 1800. But then the “Quasi War” with France suddenly ends, as Napoleon decides to focus on the conquests on the continent begun in 1796 in Italy and Austria. He sells the Louisiana territory to President Jefferson in 1803, confident that he can take it back by force if need be at a later date.

Thomas Jefferson, an outspoken Francophile, inherits Adams’ problem and is likewise caught in the middle. In 1805 the British begin to “impress” American sailors to serve on Royal Navy warships fighting the French. The U.S. Senate condemns the action. Then in 1807 the USS Chesapeake is bombarded off Norfolk, Virginia, by HMS Leopard with 21 casualties and four men impressed. Instead of declaring war on Britain, Jefferson equivocates by sending his Embargo Act of 1807 to Congress, barring all U.S. ships from sailing to any foreign ports. This cripples the American economy, and Jefferson is forced to repeal it before leaving office in 1809.

Now comes Napoleon’s turn to manipulate America once again. He does so by promising President Madison that France will not interfere with America’s ship if it promises to stop trading with the British. Madison naively falls for this, and, on November 2, 1810, he declares that the U.S. will end all commercial exchanges with Britain.

The declaration outrages the British who now regard America as a French ally. Tensions rise and on May 1, 1811 the HMS Guerriere impresses another sailor after stopping the USS Spitfire off the coast of New Jersey. On May 16, the USS President responds by attacking the HMS Little Belt near North Carolina, with 11 British sailors killed and 21 others wounded.

In addition to the conflicts at sea, it also becomes apparent that Britain is supporting tribal uprisings against America — most notably Chief Tecumseh’s confederation of Shawnee and Miami warriors in southern Indiana at the November 11 Battle of Tippecanoe.

At this point President Madison is being carried along by calls for war with Britain emanating from the public, the politicians and his generals. His new Secretary of State, James Monroe is a former front line officer and combatant in the Revolutionary War, and ready to take on the British again. He is joined by two new members of the House, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, who together rally a faction in Congress known as the “Warhawks.”

They see the continued presence of the British in Canada as “unfinished business” from the Revolutionary War. This inhibits the growth of America’s fur trading industry, provokes tribal resistance on the frontier, and presents an invasion threat with redcoat troops garrisoned in forts along the border.

Sensing war, Congress also gives Madison authority on April 10, 1812 to call up to 100,000 troops from state militias, should the need arise.

American and British diplomats attempt to search for peaceful ways out, but Britain demands the right to retrieve “its nationals” serving on American ships in order to win its naval battles with the French. So the time for compromise runs out.

On June 1, 1812, acting in accord with the Constitution, Madison goes to Congress and asks them to declare war against Britain. His principal reasons include: ongoing impressment of seamen; blockades against American shipping; confiscation of ships; and incitement of the Indian tribes in the Northwest territories.

The actual voting is hardly unanimous. Strong opposition comes from New England where the powerful Senator Daniel Webster cites the damage to the nation’s economy and the possibility that Napoleon will be strengthened and return to America. The House supports the war measure by 78-45; the Senate is much closer, with passage by only 18-13. The outcome is determined on June 4 along party lines – with no Federalists supporting the President.

With passage of the bill, “Mr. Madison’s War” is about to begin.

While Madison believes an easy victory will follow, he has failed woefully to prepare a military force sufficient to carry the day. The U.S. Army numbers only 12,000 Regulars; so much of the fighting will depend on often poorly trained state militias. The U.S. has the largest “neutral” fleet in the world, but it will be no match for the Royal Navy. And since Congress has shut down the US Bank, access to funding the war will be constrained.

Fortunately for the president, the British are similarly ill-equipped to fight.

In June 1812 the bulk of their ground forces are attacking the French in Spain, under the future Duke of Wellington. Only 6,000 red coats have been left behind in North America to defend various Canadian forts. Likewise the British navy has its hands full trying to enforce the blockade of cargoes flowing into France.

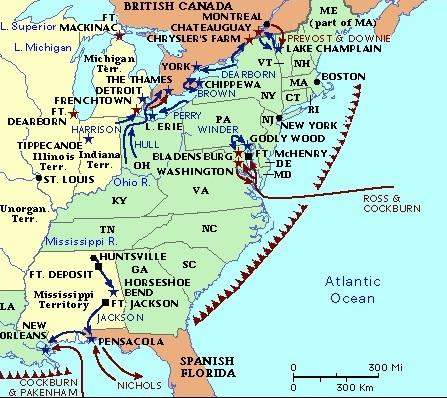

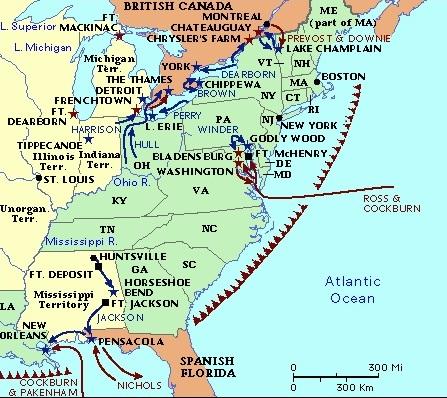

The War of 1812 that follows will be fought on land and water in three separate theaters and phases:

- Along the Canadian border – with the U.S. trying to invade north, and Britain, with certain tribal allies, threatening territories from Ohio to Michigan.

- * On the Atlantic coast – featuring the British naval blockade and eventually leading to the short-lived thrusts against Washington and Baltimore.

- In the deep South – culminating in a landmark battle around New Orleans.

It will end when both sides recognize that the costs of continuing to fight outweigh the realistic gains left to be had.

The War in Canada Begins Badly For America

As in the Revolutionary War, the U.S. assumes that a quick strike into Canada will succeed, and perhaps even cause the British to back away from further fighting. As Thomas Jefferson says:

The acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching.

So the battle begins, with the opening gambits along the western edge of Lake Erie and north into Lake Huron. But almost immediately things go badly for the US forces.

On July 17 a contingent of 200-300 British and Indian warriors land on Mackinac Island where American troops are garrisoned at Ft. Michilimackinac. Their commander, Lt. Porter Hanks, is unaware that the war has begun and is taken by total surprise. He surrenders post haste on the belief that he is badly outnumbered. Soon after two U.S. sloops are also captured when they come into port believing that the fort is still in friendly hands. Hanks is subsequently court marshalled for cowardice, but is killed by a British shell while still under arrest at Ft. Detroit.

Command of the “Army of the Northwest” lies with Brigadier General William Hull, a Revolutionary War veteran praised by Washington, and presently Governor of the Michigan Territory. But Hull is 59 years old, and has tried, unsuccessfully, to avoid the “offer” from Secretary of War Eustis to return to combat.

When Hull learns of the Mackinac Island debacle, he fears that Ft. Dearborn in Chicago may also be attacked and overrun. He orders the immediate evacuation of the fort. On August 15, some 66 soldiers and 27 women and children evacuate under a flag of truce, only to be set upon by Potawatomi warriors who kill over half of the Americans and capture the rest.

While these two reversals are occurring, Hull and 2,500 troops are preparing to invade Canada along the western edge of Lake Erie. On July 5, 1812, Hulls sets up camp at Ft. Detroit. One week later he crosses the Detroit River, and issues a proclamation meant to scare his opponents into submission:

INHABITANTS OF CANADA: I have a force which will break down all opposition, and that force is but the vanguard of a much greater. If, contrary to your own interest, and the just expectations of my country, you should take part in the approaching contest, you will be considered and treated as enemies, and the horrors and calamities of war will stalk you.

Once on Canadian soils, Hull encounter resistance from a mixture of British regulars, local militia and various tribesmen, notably Tecumseh’s confederation. By August 9, the set-backs convince Hull that he cannot advance into Canada without more troops and cannon, and he retreats back over the river to Ft. Detroit.

By now, however, the British are ready to go on the offensive and chase him. They assemble a force of some 300 Regulars, 400 militia and 600 Indians at the Canadian town of Amherstburg, then head out after Hull and his remaining 2200 men at Detroit.

The red-coat commander, Major General Isaac Brock, decides to bluff Hull into believing he is surrounded by overwhelming opposition. His dispatch to Hull also raises the specter of uncontrollable slaughter waged by his tribal bands:

The force at my disposal authorizes me to require of you the immediate surrender of Fort Detroit. It is far from my intention to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware, that the numerous bodies of Indians, who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences…

On August 15, Brock fires on the fort, using the few cannon at his disposal, along with support from two Royal Navy sloops on the nearby river. Hull has his daughter and grandchild in the fort, and fears a repeat of the slaughter at Ft. Dearborn. He asks Brock for three days to arrange for surrender; Brock gives him three hours.

When news of the capitulation at Detroit reaches Washington, Hull is arrested and his command is handed to William Henry Harrison. A subsequent court martial sentences Hull to death, but his sentence is commuted by Madison, in light of his long service during the Revolution and his advanced age.

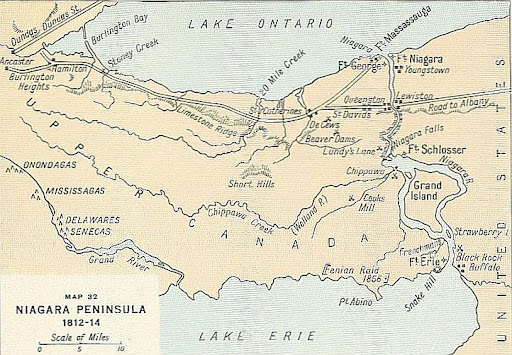

The next American attack takes place on October 13, 1812, some 200 miles to the east of Detroit at Queenston Heights, just north of Niagara Falls. It pits a new U.S. commander, General Stephen Van Rensselaer and his 3500 troops against some 1300 British regulars and Mohawk warriors under Major General Isaac Brock, who had thrashed Hull eight weeks earlier.

Van Rensselaer is a political appointee, with limited training in warfare. His attack is poorly planned, an attempt to move from the east, via Lewistown, across the Niagara River and up a 300 foot incline to the entrenched British defenders. As the American cross over by boats, they come under withering fire from the British. Van Rensselaer fights heroically, while being hit six times by musket balls. But only a fraction of his forces cross the river, while the bulk cower in safety on the other side. Finally, those who crossed are forced to surrender.

The Americans suffer 270 killed or wounded and another 800 captured; British losses are around 100 men, most notably General Brock, who dies leading a charge. Van Rensselaer survives his wounds, but resigns his command.

These reversals drive increased criticism of Adams’s overmatched Secretary of War, William Eustis. Madison wishes to replace him with Secretary of State, James Monroe, a Revolutionary War combat veteran, but Monroe declines. So instead, on January 13, 1813, Madison chooses John Armstrong, former Revolutionary War fighter, U.S. Senator from New York, and ambassador to France.

America Scores Victories At York, The Niagara Forts And Detroit

It is not until the spring of 1813 that fortunes begin to turn for the Americans in the Canadian theater. The strategy belongs to Armstrong, and it involves gaining control over Lake Ontario.

On April 27, 1813, General Zebulon Pike, the western explorer, sails from Sackett’s Harbor along with 1700 troops to capture the provincial capital town of York (Toronto), situated on the northwest edge of the lake. The disorganized British defenders are quickly overwhelmed,

although Pike is killed when a magazine is blown up during the battle. Over the next two days the U.S. forces plunder and set fire to private homes and to the Legislative Assembly – a favor the British will return 16 months later in Washington.

Once York is secured, the American forces turn south to the two key British forts along the Niagara River, Ft. George on the southern shore of Ontario and Ft. Erie some 25 miles below it on Lake Erie.

The defenders of Ft. George expect the Americans to bombard and attack from their base at Fort Niagara on the east side of the river. But instead they come in landing craft on Lake Ontario, led by Lt. Colonel Winfield Scott, whose gallantry in the battle earns him lasting fame.

On May 27, the British commander, fearing encirclement, abandons Ft. George and retreat south, past Niagara Falls, and toward Ft. Erie.

Ft. Erie is the oldest British bastion in Ontario, and it is supported by royal navy vessels under Commander Robert Barclay. On the morning of September 10, 1813, he steers his six ship flotilla into a line of battle engagement with nine smaller U.S. ships under Admiral Oliver Hazard Perry. By 3PM, the Americans have won the day, and Perry sends off a message to General William Henry Harrison, who is leading ground troops against the fort itself:

General. We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop. Yours. Perry

The Battle of Lake Erie is modest in size, but strategically important. It signals America’s growing naval strength, and it inhibits potential British and tribal incursion into Ohio, Pennsylvania and western New York.

Next comes an equally important victory, back west toward Detroit, in the Battle of the Thames.

With Perry and the American fleet now in control of Lake Erie, the British garrison at Detroit is immediately vulnerable. The commander, Major General Henry Proctor, moves his 800 regulars inland, to the east, along the Thames River. He is accompanied by a contingent of some 500 mostly Shawnee warriors, led by Tecumseh.

Harrison’s forces number 3700 men, and he comes onto the retreating British on October 5, 1813, in a swampy area, some 65 miles upriver, near the town of Thamesville.

The redcoats are half-starved, fire off a few desultory rounds, and then surrender. Not so the Shawnees. They put up stiff resistance – led by Tecumseh, who dies in battle. His death ends the threat of coordinated tribal and British action against the northwestern territories. And it propels the victorious “Tippecanoe” Harrison even further into the national spotlight.

After Thames, the Americans are happy to let the border war with Canada stabilize.

But now the British refuse to cooperate.

By December 1813, they have retaken control of Ft. George along with America’s Ft. Niagara, and begin to consolidate their forces for a drive south down the Niagara River toward Ft. Erie.

By July 5 they are some sixteen miles north of the fort when their progress is halted by American forces under General Winfield Scott at the Battle of Chippewa. Both sides suffer over 300 casualties before the redcoats withdraw from the field.

Three weeks later, on July 25, 1814, the fighting resumes, this time at Lundy’s Lane in the bloodiest single battle of the war. The site of the clash is in Canada, roughly two miles west of Niagara Falls, the border line between New York to the east and Ontario to the west.

This engagement pits 3500 troops under British Generals Drummond and Riall against 2500 Americans under General Jacob Brown who come out to meet them.

This battle lasts from morning to midnight, ending in a stand-off. Casualties approach 875 men on each side. Winfield Scott suffer a severe wound to his left shoulder, which puts him out of the war. But his penchant for military drilling and leadership earn him the lasting moniker of “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

While both generals claim victory at Lundy’s Lane, the British continue their march south, and begin a siege of Ft. Erie, occupied since July 13 by the U.S. troops under General Edmund Gaines. The siege lasts for a month, before the British lift it on September 17, 1814.

At this point the conflict along the Canadian border is essentially over.

The easy victories that Madison expected in 1812 have never materialized. However, the Americans have proven again that they can hold their own with Great Britain, even in modest naval actions like the Battle of Lake Erie.

And, with the death of Tecumseh, they have diminished the threat of a tribal coalition, backed by the British, impeding westward expansion from Ohio to the Mississippi.

Important Battles of the War of 1812: Northern Phase

| 1812 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| July 17 | Ft. Michilimackinac | Canada | British | 60 | An opening loss for the Americans |

| August 15 | Ft. Dearborn | IL | British | 100 | Gen. Hull court-marshalled for surrender |

| October 13 | Queenston Heights | Canada | British | 1,100 | Wounded Van Rensselaer resigns after loss |

| 1813 | |||||

| April 27 | York | Canada | US | 800 | Americans sack Canada capital city |

| May 27 | Ft. George | Canada | US | 500 | Winfield Scott forces abandonment |

| September 13 | Ft. Erie | Canada | US | 2,600 | Major naval victory for Admiral Perry |

| October 5 | Thamesville | Canada | US | 1,000 | Tecumseh killed in action |

| December 19 | Ft. Niagara | Canada | British | 450 | Successful night assault by British |

| 1814 | |||||

| July 5 | Chippewa | Canada | US | 600 | Scott stops British momentum |

| July 25 | Lundy’s Lane | Canada | Draw | 1750 | Bloodiest of war; ends north phase |

| Sept 17 | Ft. Erie | Canada | US | — | British finally lift siege |

Britain Dominates The Atlantic Coast Until Stopped At Baltimore

Britain’s Royal Navy dominates the second theater of war – on the seas off the Atlantic coast – with a blockade that essentially shuts down America’s international commerce, and leads to a renewed secession threat by the New England states.

When hostilities break out, the British have 85 warships already patrolling American waters to enforce their ban on cargoes headed toward Napoleon’s France.

The United States, on the other hand, begins with a fleet of 21 ships, composed of:

- 0 “ships-of-the-line,” three-masted, multi-decked 74 gunners for broadside attacks.

- 8 “frigates,” also 3 masts, but lighter and faster with one deck of 28-44 guns.

- 13 smaller escort ships, war sloops, brigs and schooners, with 12-18 guns apiece.

With this limited force, all the Americans can hope to do is occasionally break out of their ports and go after an isolated foe.

And one such opportunity arises early in the war, on August 19, 1812, when the frigate USS Constitution – 44 guns and 456 sailors under Captain Isaac Hull – wins an intense five hour battle with the 38-gunned HMS Guerriere, off the coast of Halifax. This victory, the first of five that Constitution will record over British warships, earns the frigate its lasting sobriquet, “Old Ironsides.”

But this British defeat proves an anomaly, and the Royal Navy gradually expands it stranglehold on the east coast sea lanes. By the end of 1812 they have shut down American shipping from the Chesapeake Bay, marking the Virginia coast, through South Carolina.

In April 1814, they extend their tight blockade north into New England, which further stirs opposition to Madison’s conduct of the war in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Both states have refused to place their militia under the federal War Department, and, in turn, Madison has denied them federal funding support for their own defense.

This further prompts the question: is the government effectively protecting the nation?

In August 1814, both the New Englanders and the entire nation are reminded of the mortal danger posed at any moment by the powerful British navy. By this time, Napoleon has been exiled and Britain is able to free up more land troops to fight the Americans.

One of these is the Dublin born Major General, Robert Ross, who has fought valiantly alongside Wellington, and is now given command over all army troops. Along with his naval counterpart, 3-star Vice Admiral George Cockburn, Ross plans a two-pronged assault aimed at his opponent’s heart, the capital city of Washington.

The plan involves a naval flotilla consisting of 4 ships-of-the-line and 20 more frigates and war sloops, under Admiral Alexander Cochrane, along with amphibious landing crafts to carry Ross and his 4,400 men, mostly veteran Royal Marines.

On August 19, Ross disembarks at Benedict, Md. and begins marching northwest toward the town of Bladensburg, about 10 miles above Washington, on the east branch of the Potomac River. Once there they encounter an American force consisting of 6500 Maryland militia and 400 U.S. Regulars under Brigadier General William Winder.

The August 24, 1813 Battle of Bladensburg proves to be one of the greatest routs in American military history. Winder has aligned his troops poorly and they are decisively thrashed by Ross. Lacking any pre-planned line of retreat, the U.S. forces turn tail and dash for Washington, DC, 10 miles to the southwest. This flight, which includes both President Madison and Secretary of State Monroe, is immortalized as “The Bladensburg Races” in a satiric British poem in 1816.

Away went Madison, away Monroe went at his heels,

And all the while his laboring back, a merry thumping feels.

But the worst is yet to come on this day at Washington City. Secretary of War Armstrong is certain that the British will never reach the capital, and has made essentially no preparations to defend it.

Ross’s troops arrive in the capital by evening on the 24th and are shot at when they approach under a truce flag. This leads to a 26 hour rampage in which the Capitol, the White House and the US Treasury are all pillaged and burned – in return, the British claim, for similar destruction of their provincial capital of York in April, 1813.

With the US government stunned and momentarily homeless, Ross and his troops exit Washington to rejoin Admiral Cochrane’s flotilla on August 26th and take aim at their second objective, capturing the critical port city of Baltimore.

On September 12, Ross disembarks at the town of North Port, on Chesapeake Bay, twelve miles southeast of Baltimore. But now the Americans are ready for him.

General John Stricker has laid out a strong defensive position at North Port. These include redoubts around the city, marked by tidal swamps and creeks that force the British to funnel through a narrow strip of land, where his 3200 Maryland militia men wait in ambush.

While the battle ends after two hours with the Americans withdrawing, the British suffer a crucial loss when General Ross is mortally wounded by a musket round that strikes him in his right side.

On September 13, the Battle of Baltimore hangs in the balance.

The now 5,000 strong British ground troops, under Colonel Arthur Brooke, encounter very stiff resistance at Hampstead Hill from what has grown to be 11,000 militiamen, led by Generals Stricker and William Winder. At 3AM, Brooke concludes that the initiative is lost, and begins to withdraw his men.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy is encountering similar opposition on the water.

Admiral Cochrane sails his 19 ship flotilla into Baltimore Harbor, briefly exchanges cannon fire close up to the American defenders in Ft. McHenry, and then anchors just beyond range of the fort’s guns.

He then proceeds to bombard the Americans for almost 25 straight hours, until daylight on the 14th – when the Americans send aloft an oversized flag signaling their ongoing presence within the Fort.

In the harbor, a 35 year old American lawyer named Francis Scott Key, on board a British ship to conduct a goodwill mission for President Madison, watches the bombardment through the rainy night, wondering what the morning of September 14 will bring.

At dawn, Key glimpses the Stars and Stripes still flying over the ramparts. The Americans have held Baltimore, and Key is moved to capture the moment in words.

Oh say does that star spangled banner yet wave o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

After the stalemate along the Canadian border and in the harbor at Baltimore, both nations are growing weary of the now two year old conflict. The war in the two northern theaters is over.

Important Battles of the War of 1812: Atlantic Coast Phase

| 1814 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| Aug 19 | Halifax | Ocean | US | — | USS Constitution defeats HMS Guerriere |

| Aug 24 | Bladensburg | Md | British | 400 | General Winder’s humiliating route |

| Aug 24 | Washington | DC | British | 40 | Capital sacked as revenge for York |

| Sept 12-14 | Baltimore | Md | US | 550 | Ft. McHenry withstands bombardment |

The War Ends With An American Victory At New Orleans

After Baltimore, one more great battle remains to be fought in the third theater of the war, the deep South, at New Orleans.

One figure dominates events in the deep South during the War of 1812: Andrew Jackson, Major General of the Tennessee militia. Jackson is 45 years old when the second conflict with Britain begins. He has been in the militia since fighting in the Revolutionary War at age thirteen and has lived on the western frontier since 1787. He is a natural leader, the right man to lead American forces in the interior.

He does so in the two important battles that take place in the South. The first is at Horseshoe Bend in what will become Alabama, the other at the port of New Orleans.

The war is nearing the two year mark on March 27, 1814, when Jackson approaches an Indian camp nestled in a bend in the Tallapoosa River. The General is accompanied by a force of 2,700 militia and another 600 Cherokee and Choctaw tribesmen.

The encampment they encounter consists of some 700 “Red Stick” Creeks, the one tribe that Chief Tecumseh has previously recruited to fight alongside his Shawnees and the British.

While the Creeks feel safe surrounded by the river, the fact is that they are trapped in a cul du sac, with only one narrow pathway in and out over open ground. When the Red Sticks throw up breastworks to defend this camp entrance, Jackson attacks it repeatedly with artillery and charges and also sends probes across the river into their rear. After some five hours of battle, the Creeks disintegrate, with upwards of 80% of their number being killed, wounded or captured.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend ends the Creek resistance, and at the Treaty of Fort Jackson on August 9, the Nation cedes 23 million acres of their land to the U.S. In addition to Jackson, two other American fighters – Sam Houston and Davey Crockett – both win fame from this fight.

For the next nine months, Jackson drifts south into the Florida panhandle before turning west toward Louisiana after learning that the British intend to capture New Orleans.

The British campaign will be led by General Edward Packenham, a veteran of the Napoleonic wars, and brother-in-law of Wellington, who sails in late November from Jamaica with 18,000 crack troops toward New Orleans.

But Packenham and Admiral Alexander Cochrane first need to choose how best to approach the city. One path is to send British ships up some 100 twisting miles up the Mississippi, past Ft. St. Philip and other outposts, and attack from the south to north. The other, which Cochrane chooses, is to locate the fleet in the Gulf of Mexico, just below and to the east of Lake Pontchartrain – and attack overland for some 15 miles from the east.

On December 12, Cochrane anchors on Lake Borgne at Fisherman’s Village, and Packenham disembarks. He does not, however, race directly toward the prize, instead choosing to proceed at a leisurely pace to set up a base camp and prepare his eventual assault.

This delay gives General Jackson, who doesn’t arrive in New Orleans until November 30, the time he needs to organize his opposition.

When he hears on December 23 that Packenham’s advance guard of 1800 troops under General John Keane have reached the Mississippi at Lacostes Plantation, some 7 miles downriver from the city, he sets in motion a three-pronged attack against the encamped British.

His rallying cry at the moment is pure Jackson, the leader of men into battle: “By the Eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil.”

The battle on the 23th proves a stand-off, but it again slows down the British move north to New Orleans and gives Jackson even more time to build defensive positions.

Ironically, on December 24, 1814, diplomats from Britain and the U.S. in Belgium are signing the peace Treaty of Ghent ending the war. Word of this, however, does not reach America until February 16, 1815.

On December 28, Packenham sends out probing attacks to find the enemy, which he does on January 8, 1815. With all of his 8,000 troops on hand, he advances from south to north against the “Jackson Line” set up at Chalmette Plantation, five miles below New Orleans.

Jackson’s main position is flanked on his right by the Mississippi River and on the left by swampland. He has arrayed his 4,000 militia and 16 cannon behind breastworks that run roughly a thousand yards in from the river to the swamp. Across the riven, he has also stationed a force to protect his right flank.

Packenham’s strategy is to drive two separate columns of redcoats straight at Jackson, while also sending a detachment across the river to try to enfilade the Americans on their right. But the later maneuver develops too slowly for the General.

So he sends his lines forward, as the overnight fog lifts on the field leading to the US positions. First it is General Gibbs with 3,000 men on the British right, who try to force Jackson, but are turned back well short of the ramparts.

Seeing this repulse, Packenham himself leads Keane’s left-side column of 900 Highlanders in an oblique march across the face of the American guns – to join Gibbs in a second charge. But chaos accompanies this assault, as the British command is cut down one by one.

Packenham is wounded by gunfire in the left knee, then the right arm, and finally is hit by a shell that severs an artery in his leg, bleeding him out in minutes. Gibbs receives a mortal wound in the neck and Keane is also wounded and carried from the field.

Still the British make a third and final assault on their right, led by a Major, the highest ranking officer left. This time they penetrate all the way into Jackson’s lines, before being turned back – effectively ending the battle.

Jackson has triumphed and saved New Orleans!

And the casualty figures prove the size of the victory, the defensive minded Americans suffering 101 killed, wounded, and captured, to 2,037 for the attacking British.

After the battle, Andrew Jackson is hailed as a national hero, and begins his trail toward the presidency. Edward Packenham, a hero of the day in his own, has his body packed into a preserving cask of rum and shipped home to Ireland for burial.

Important Battles of the War of 1812: Southern Phase

| 1814 | Battle | State | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| March 27 | Horseshoe Bend | Ala | US | 1,300 | Jackson defeats Red Stick tribe |

| 1815 | |||||

| January 8 | New Orleans | La | US | 3,100 | Triumphal win after peace treaty signed |

The Treaty of Ghent Ends The War

The Treaty of Ghent ending the war is signed by two American emissaries – John Quincy Adams, serving as Ambassador to Russia, and Speaker of the House, Henry Clay – and their British counterparts on December 24, 1814. But news of the agreement does not reach America until February 16, 1815, nearly six weeks after the New Orleans battle. The Senate approves the treaty on February 17 and the war is officially over.

The toll on both sides has been high. Britain has lost 1600 killed, 3700 wounded and another 3300 lost to disease; American losses are even higher, 2260 killed, 4500 wounded and 8000 dead from illnesses. In monetary terms, the bill is roughly $100 million for each side.

Estimated Casualties Of America’s Two Wars With Britain

| Revolutionary War | Years | Killed | Wounded | Disease | Total |

| America | 1775-1783 | 8,000 | 25,000 | 17,000 | 50,000 |

| Britain | 4,000 | 12,000 | 8,000 | 24,000 | |

| Germans | 1,800 | 3,700 | 1,700 | 7,500 | |

| War of 1812 | |||||

| America | 1812-1815 | 2,260 | 4,500 | 8,000 | 14,760 |

| Britain | 1,600 | 3,700 | 3,300 | 8,500 |

And to what end, the costly War of 1812?

Neither side has won new territory from the other, and a major cause of the war – the British practice of seizing American sailors – has ceased long ago with the defeat of Napoleon..

Still the United States has some positive things to show for the 30 month conflict:

- The threat to western settlers from Tecumseh’s confederated Indian tribes affiliated with Britain has been diminished.

- A series of future national leaders have emerged from the events, Harrison, Scott and Jackson on the military side, Henry Clay in particular on the political front.

Of greatest importance, America has once again demonstrated to itself, and to the world, that it has the might and will to hold its own against the powerful British lion.