Section #1 - The French and Indian War

The French & Indian War: 1754-60

French & Indian War: 1756-1763

Between 1756 and 1763 France and Britain fight the Seven Year’s War, the first true conflict for global hegemony. It pits France, Austria, Spain, Sweden and Saxony against an alliance of England, Prussia, Portugal and Russia. It is fought on land and sea, with human casualties estimated at well over one million men, and fearful financial losses on all sides.

The American theater is christened the French & Indian War, with the action beginning in 1754. At that time, the British have over a million subjects scattered along the east coast, while the French number only 60,000 along the Canadian border from Quebec down through the Great Lakes and over to the Mississippi River.

Both sides hope to dominate the fur trade and to expand their land claims on the continent.

Success hinges heavily on controlling two geographical areas:

First, the Ohio River Valley region, some 200,000 square miles from western Pennsylvania above Pittsburg across the lower border of Lake Erie to the Maumee River below Detroit, then well south into eastern Indiana.

Second, the twin water routes into eastern Canada and the French cities of Montreal and Quebec: the Lake Erie-Lake Ontario-St. Lawrence Seaway chain to the west; and the Hudson River-Lake George-Lake Champlain chain to the east.

In April 1754, the French make the first move here by constructing Ft. Duquesne. It is located below Lake Erie, at the headwaters of the Ohio River at modern day Pittsburg. The British respond with a reconnoitering party led, ironically, by a 22 year old Lt. Colonel named George Washington of the Virginia Militia. He is joined by 40 local militia and a few Seneca warriors. On May 28, 1754, they ambush a small French company under Ensign Joseph Jumonville, killing him and inflicting 30 total casualties. After defeating Jumonville, Washington builds Ft. Necessity nearby his campsite at Great Meadows, Pennsylvania.

In addition to the Ohio Valley, the British hope to challenge the French in eastern Canada. On June 17, British General Robert Monckton and his 2300 troops assault Ft. Beausejour, a French outpost on the far northeast corner of Acadia. The undermanned defenders surrender and the locals are given the choice of loyalty to Britain or expulsion. Some 11,000 choose the later, most returning to France, but some to New Orleans, where linguistic corruption leads to the name of “Cajuns.” The victory secures Nova Scotia for the British.

Washington’s Ft. Necessity is hardly up when an overwhelming force of 300 French Canadians and Native Americans led by Jumonville’s brother surrounds the structure and forces him to capitulate on July 3. After receiving the news of this loss in the Ohio River Valley, London blames Washington and decides to send British Regulars across the Atlantic to defeat the French. An angry Washington resigns his militia commission on July 17, only to soon rejoin the British army as a Regular to fight on.

Major General Edward Braddock is chosen by King George II to serve as Commander-in-Chief over all British forces. On February 20, 1755, he lands at Hampton, Virginia, with two regiments of the Coldstream Guards and begins to organize his army. He arrives at an aggressive plan to split his forces and attack four key French forts simultaneously.

On July 9, 1755, Braddock heads toward his own target at Ft. Duquesne only to meet with disaster. His men are attacked on the way to the fort by a mixed force of Indians and Frenchmen hidden in the woods. The Battle of the Wilderness is three hours old when Braddock is mortally wounded by a shot that pierces his lungs. Fearing a massacre, the British troops bolt in a panic. Of the 1300 men under Braddock, almost 900 are killed or wounded. Those captured are systematically tortured and scalped. Among the participants are two notable Americans, Daniel Boone and, again, George Washington, with Washington said to have formed a rearguard to help save the fleeing redcoats. Braddock is succeeded as army head by William Shirley, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Province.

After Braddock’s loss, the British get some good news on September 9, 1755 from upstate New York. There William Johnson, recently a British trade agent with the Iroquois nation, wins the Battle of Lake George. To consolidate the victory, Johnson builds Ft. William Henry with the intent that is will be a portal for a British advance north to attack Ft. Carillon (later Ticonderoga) at the foot of Lake Champlain, then move against Montreal and Quebec City.

In May 1756 King Louis XV sends his own man to command all French forces on the continent. He is a 43 year old aristocrat, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, a tested combat veteran, having engaged in many prior campaigns while suffering multiple saber and firearm wounds. Upon arrival in Montreal, his priority lies in preventing any more French losses in Canada.

Montcalm’s first move, on August 14, is west against Britain’s Ft. Oswego on the shore of Lake Ontario. His 3,500 troops attack from all sides, killing the commanding officer and forcing the surrender of some 1700 men. With this victory, the French have found their right leader for the fights ahead.

One year later, on August 3, 1757, Montcalm turns east with a siege against Britain’s Ft. William Henry, built after William Johnson triumph in 1755. It is located 200 miles east of Ft. Oswego on Lake George, the gateway to Lake Champlain and Montreal. The British fort is in the shape of a square, with its northern ramparts facing the water. Montcalm comes up on the fort with 6200 French Regulars and 1800 Huron tribesmen, entrenches along the western and southern walls and begins bombarding the wooden fort with heavy artillery, including two giant cannons capable of sending 32 pound iron balls over a 500 yard range.

Huddled inside are 2300 troops including Regulars and colonial militia under the command of Lt. Colonel George Munro, who pleads for reinforcements from General Webb, twenty miles south at Ft. Edward. But they never arrive and, after four more days of cannon fire, Munro agrees to surrender on August 8. Montcalm ushers the British survivors out of the fort but then is unable to restrain the Huron from attacking their column and massacring up to several hundred, including women and children. The American author, James Fennimore Cooper, will dramatize the events at Ft. William Henry in his 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans.

By 1758 Britain is discouraged by its showing in North America and House of Commons leader William Pitt the Elder orders an offensive campaign to leverage its lopsided advantage in resources. This leads to the bloodiest battle on American soil which occurs on July 6-8, 1758.

The scene is the French Ft. Carillon, strategically important for blocking the entrance to Lake Champlain. On July 6, 1758, British Generals James Abercrombie and George Howe land some 18,000 troops, including 6000 Regulars, at the top of Lake George, and proceed to march overland to attack the fort from the northwest. They outnumber the defenders by 5:1 and are confident of victory.

But Montcalm outsmarts them. Rather than waiting for a hopeless siege, he decides to come out of the fort and create a tight defensive position on Rattlesnake Hill including trenches and breastworks. Meanwhile the cocky British generals agree to forego an artillery attack in favor of a mass frontal assault on the French lines. This begins around noon on August 8 with the first infantry wave quickly thrown back. Abercrombie persists with two more waves which also fail, and by nightfall the British begin their retreat to Lake George. The in-action casualties – 2600 for the Redcoats and 750 for the French – are unsurpassed by any other engagement in the war. For his part in the fiasco, Abercrombie is recalled to England.

Montcalm’s victory at Ft. Carillon, however, is the high water mark for the French in North America. From that point on the tide turns decisively in favor of Britain.

Exact reasons for this seem partially mired in the national interests associated with the Seven Year’s War in Europe, with the French concentrating more resources there than the British, relatively safe on their island refuge. Beyond that, Britain’s long-range commitment to North America is, and will continue to be, much greater than France’s. This is true even after Napoleon returns France to the glory is loses in the Seven Year’s conflict.

Once William Pitt decides in 1758 that winning North America is vital to Britain, he pours in the resources that make the difference.

British momentum begins in the Canadian theater at the French Ft. Louisbourg, located at the northeast tip of Nova Scotia. Its role has been to block the British navy from entering the St. Lawrence Seaway and sailing down to attack Quebec City and Montreal. The British, under General Jeffrey Amherst, bring overwhelming support to the task: 40 men-of-war and 14,000 Regular infantrymen on some 150 transport ships. Second in command, General James Wolfe, lands the first troops on June 8, beginning a 50 day siege. This ends after the navy finally enters the harbor for close-in bombardment of the fort. On July 28, 1758, Louisbourg surrenders along with its 7,000 man garrison.

The British next turn their sights to Ft. Frontenac at the far south end of the St. Lawrence Seaway where it join Lake Ontario. Frontenac has long served as both a fort, a trading post, and a transport hub for shipping supplies from the Ohio Valley to French Canada. But by the summer of 1758, its garrison has been stripped down to only 120 troops as attrition takes its toll on French resources. So it is an easy target for General John Bradstreet and his 2600 man force who force a surrender on August 28.

Between Louisbourg and Frontenac, the St. Lawrence is now wide open to the Royal Navy.

Two months later comes another important move by the British. From the beginning its tribal support is limited to the Iroquois and Mohawks in the northeast, while the French enjoy much broader backing from the Algonquin, Ottawa, Delaware and Huron in the east and the Shawnee in the west. To further reduce French manpower, the British and thirteen tribal chiefs sign the Peace Treaty of Easton (Pa.) on October 26, 1758.

As 1758 nears an end, the conflict shifts back west as the British attempt to redeem General Braddock’s earlier defeat at Ft. Duquesne. They assemble a 6,000 man force, including Virginia militia under George Washington, to make the attack. But instead of following Braddock’s well-known southern route to the fort, they mistakenly opt a new northern route which requires extensive road construction.

Frustrated by repeated delays, commanding General John Forbes sends an advance brigade of 750 Scotch Highlanders under Major James Grant ahead on September 7 to reconnoiter the fort. They arrive on September 15, with Grant convinced that only a few French troops are inside, and that he can conquer the fort on his own. His first attempt fails falls apart when his men lose their way in the surrounding woods. He then blunders by dividing his force into several smaller wings hoping next to ambush the enemy.

But inside the fort is none other than General François-Marie de Lignery, who helped mastermind Braddock’s defeat in 1755, and now commands a mainly tribal contingent, including 500 warriors. The Frenchman wastes no time, striking first and routing Grant with only 20 casualties of his own. The redcoats lose more than 200 before fleeing and Major Grant suffers the further humiliation of being captured.

By the time the main British force under Forbes shows up on November 24, they find hat General de Lignery has burned the fort, blown up the magazine, and headed west to link up with Montcalm in Canada. They also find the decapitated heads of the Highlanders stuck on poles along with their kilts. After the battle George Washington, Colonel of the Virginia Regiment, resigns his commission for good and returns home. The site of Ft. Duquesne is renamed Ft. Pitt, after the British politician, and the settlement of Pittsburg is born.

With Ft. Duquesne in Forbes hands and the isolated Ft. Niagara left vulnerable, the French know that they have lost the fight our west for the Ohio Valley. In turn, they shift their remaining resources toward eastern Canada, determined to defend their two main bastions at Montreal and Quebec City.

The architect of the plan to conquer both is General Jeffrey Amherst, hero at Louisbourg and now Commander-in-Chief of all British armies. His first move is against Ft. Carillon, where Montcalm had defeated Abercrombie a year earlier. Despite its importance as a barrier to Lake Champlain, France’s lack of manpower means that only 400 troops are there to defend it against the approaching redcoats. Montcalm sends a message to the fort commander to destroy the fort, but all he is able to do in time is blow up the magazine. The remaining structure belongs to Britain as of June 27, 1759. They will rename it Ft. Ticonderoga, the Iroquois word for “between two waters” (Lakes George and Champlain), and will utilize it in their drive toward Quebec City.

With Ft. Carillon out of the way, Amherst is ready to tackle the three remaining obstacles in the way of total victory: the great citadel at Quebec City, the French Ft. Niagara, and Montreal.

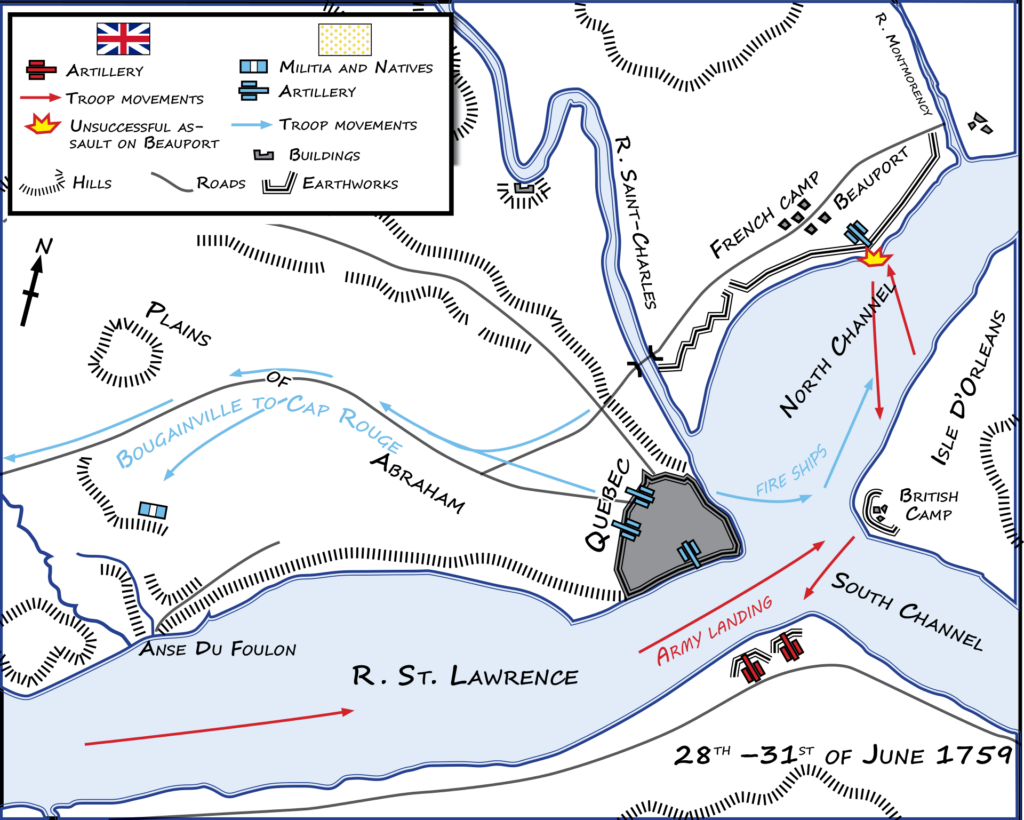

Quebec City is a formidable target, surrounded by walls and located on a promontory whose cliffs look down some 350 feet above the St. Lawrence Seaway. Amherst selects General James Wolfe and Admiral John Saunders to lead the assault. Wolfe has 7,000 veteran troops and Saunders has some 50 ships and many smaller landing craft. Together they depart southwest down the St. Lawrence and land on June 27 at Isle D’Orleans, one mile across the water from the city. From there Wolfe plots his attack strategy.

As Wolfe plans, so too does Amherst, in his case the move against Ft. Niagara, the last line of defense for supplies coming to Canada from the west. The fort sits where Lake Erie flows into Lake Ontario, some 30 miles south of present day Toronto. While the France hope to hold it, the garrison is woefully undermanned with only 500 troops and Seneca tribesmen left under the command of Captain Pierre Pouchot, a military engineer.

On July 1, Amherst orders General John Prideaux and his 4,000 men to siege the fort. They leave from Ft. Oswego and sail west along Lake Ontario before disembarking and moving into position. One wing will attack from the south, at the backside of the fort; the other across the Niagara River from the west.

When the British artillery arrives, Prideaux sends a messenger to the fort asking for a surrender. After Pouchot refuses, the bombardment begins on July 17. Knowing he cannot last for long, Pouchot sends a plea for reinforcements to General Lignery who starts out toward Niagara with 1000 infantrymen.

On the third day of the siege, General Prideaux is killed instantly when struck in the head by a piece of shrapnel from a British mortar which explodes. Command passes to William Johnson, the ex-Iroquois trade agent who won the Battle of Lake George and built Ft. William Henry in 1755. When Johnson learns of the French relief column he sends troops out to meet it two miles south of the fort at La Belle-Famille. It defeats Lignery and takes the General prisoner on July 26. Pauchot is unaware of the loss and again refuses to surrender until later that day after being escorted to see the captive Lignery for himself.

With the fall of Ft. Niagara, the western theater firmly belongs to Britain.

Meanwhile, back at Quebec City, Wolfe launches an initial attack on July 31 some 3 miles north of the city at the town of Beauport. After being rebuffed there, he continues to try to draw Montcalm out of the fort by raiding various parts of the city proper, but again without success. Finally in late August he schemes a ruse he hopes will fool the French commander.

Montcalm still believes that Wolfe will come at him from the north where the promontory cliffs around the walled city are less steep than on the south side. On September 12, Wolfe feigns another strike at Beaufort, while sending his main body south down the St. Lawrence on landing craft and past the lulled French cannons at the fort. The men land safely at L’Anse-au-Foulon and climb the cliffs, a feat Montcalm had declared impossible. They overpower a small French outpost, and by dawn on September 13, 1759, Wolfe’s 4,000 men are digging in on a field directly west of the fort known as the Plains of Abraham (after a local farmer).

Montcalm is shocked and decides to come out to meet them before they are entrenched. At 10:00am he charges forward at the head of his 3500 troops. Many, however, are inexperienced relative to the redcoats and fire their muskets before getting within range. In the melee that follows, General Wolfe is killed with one shot to the stomach and another to the chest. Second-in-command Charles Townshend takes over and the French are forced to flee the field. As they do, Montcalm is struck in the bowels, apparently by canister fire, and dies the next day.

The pivotal Battle of the Plains of Abraham lasts no more than an hour, with British casualties of 650 and French of 1,050. The redcoats control the field, but the French are able to rally, and most reach the safety of the fort. Instead of immediate pursuit, Townshend pauses for several days to assess his losses and regroup. Pierre de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, blames Montcalm for the defeat before ordering the main body of the garrison troop to flee the city for Point-Aux-Trembles, 150 miles southeast near Montreal. The fort is then surrendered on September 18 after Townshend resumes his artillery fire.

At that point, General James Murray and roughly 4,000 troops take over the citadel and prepare for the coming winter. It proves challenging what with bouts of scurvy and hunger, as the St. Lawrence freezes over and the navy can no longer deliver supplies – or military support. This sets the stage for the one final confrontation of the war.

In mid-April, the new French commander, Francois Gaston de Levis, leaves Montreal with 7,000 troops intent on regaining Quebec City. What follows is a replay of the September battle but in reverse. Once Murray learns of the approaching enemy, he comes out of the fort like Montcalm had to meet them to the west at Sainte-Foy. The two hours of combat on April 28 are even bloodier that the prior round, with over twice as many casualties. Murray is forced to retreat, but makes it back to the citadel. General Levis then tries a siege, but it proves feeble and, when the St. Lawrence melts and the Royal Navy returns, he turns back to Montreal.

General Jeffrey Amherst now holds all the cards to end the war except for Montreal, and he now sends three different commands against it. General Murray sets out from Quebec City on July 2 with 4000 men advancing along the St. Lawrence. Amherst himself begins on August 10, leaving Ft. Oswego with 3500 Regulars and 700 Mohicans, on his way up the Seaway. A day later, and in between the two, comes General William Haviland and 3500 troops along Lake Champlain.

All three wings encounter French infantry or naval resistance along the way, but still manage to take up siege positions around Montreal on September 6. By that time many of the French forces have deserted and the town is crowded with frightened civilians. General de Levis and Governor Vaudreuil confer after Amherst gives them six hours to decide before opening fire. They respond on September 7 with a list of some fifty conditions of surrender, including permission to allow the remaining troops to keep their arms marching out. Amherst rejects the plea, citing the repeated French dereliction of duty in failing to prevent atrocities against British soldiers and civilians. When the final terms are signed on September 8, they include:

- British control over all French land and possessions in North America.

- Deportation of troops back to France aboard British ships.

- Free return to France of all others who wish to depart.

- No British interference in religious practices or assets

- Canadian are allowed to retain their properties, including slaves.

With that, the French & Indian War is closed, but with one final twist. The North America conflict, along with that in Europe (which ends in 1763), brings Britain’s national debt to over L130 million. To lessen the load, the Crown decides to increase taxes on its thirteen colonies and does so without their consent. In 1775 comes another war in North America and one this time they will lose.

Important Battles: The French & India War (1754-1760)

| 1754 | Battle | Where | Winner | K/W/C | Impact |

| May 28 | Great Meadows | Pittsburg | Britain | 40 | George Washington leads ambush |

| July 17 | Ft. Necessity | Pittsburg | France | 15-20 | French defeat Washington; he resigns |

| 1755 | |||||

| June 17 | Ft. Beausejour | Acadia | Britain | ?? | Acadians expelled/Nova Scotia secured |

| July 9 | Wilderness | Pittsburg | France | 1,000 | Disastrous loss; Braddock KIA, 900 lost |

| Sept 9 | Lake George | Upstate NY | Britain | 700 | Col. William Johnson the hero |

| 1756 | |||||

| May 9 | War Declaration | Official start of Seven Years War | |||

| Aug 14 | Ft. Oswego | Far west NY | France | 1800 | Montcalm siege captures fort |

| 1757 | |||||

| Aug 8 | Ft William Henry | Upstate NY | France | 2400 | Munro surrenders & Huron massacre |

| 1758 | |||||

| July 8 | Ft Carillon | Upstate NY | France | 3300 | British lose & Lord Howe killed |

| July 26 | Louisbourg | Nova Scotia | Britain | 7400 | Opens St. Lawrence Seaway to Britain |

| Aug 27 | Ft. Frontenac | East Ontario | Britain | 120 | French lose contact with Ohio Valley |

| Oct 26 | Tribal Peace | Easton, Pa. | Britain | — | Iroquois/Shawnee/Delaware + Britain Treaty |

| Nov 26 | Ft. Duquesne | Pittsburg | Britain | 350 | French win battle but then need to retreat |

| 1759 | |||||

| June 27 | Ft Carillon | Upstate NY | Britain | — | Undermanned French abandon the fort |

| July 25 | Ft. Niagara | Lake Ontario | Britain | 800 | British complete western frontier control |

| Sept 13 | Quebec City | Quebec | Britain | 700 | Critical French loss; Montcalm & Wolfe die |

| 1760 | |||||

| April 28 | Sainte-Foy | Quebec | Britain | 2,000 | French siege fails after momentary success |

| Sept 8 | Montreal | Quebec | Britain | 3,200 | Montreal falls & French surrender |