Section #4 - Education We Receive

The Education We Receive

You are there:

Given America’s roots in English traditions and culture, the value of an education is well established from colonial times forward.

The Puritans of New England are strong proponents of literacy, and Thomas Jefferson’s 1779 “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge” in the Virginia Assembly touts its importance to sustaining a democracy.

It is believed that the most effectual means of preventing tyranny would be, to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large.

Jefferson envisions a two-tier approach to education:

One for the learned, and one for the laboring…but reading, writing and common arithmetic…should be taught to all the free children, male and female.

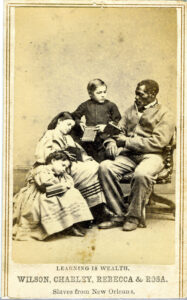

His reference to “free children” is intentional, since by law in the south, educating black people is prohibited.

The capacity to read and to write will quickly become the dividing line between those with good prospects for upward social mobility and those likely to be left behind.

In 1790 the vast majority of children experience education in a hit or miss fashion. Their teachers are typically concerned parents, most often mothers, who have received enough schooling themselves to pass along rudimentary skills, using popular “readers” and chalkboards.

There are some early signs of a wish for mandatory public schools. The Massachusetts’s Law of 1647 decrees that towns with 50 families or more hire a schoolteacher, while the Land Ordinance of 1785 requires that each plat drawn for new public domain territories set aside a 640 acre parcel for a school. However, the actual implementation of state-run school programs is still more than a half century in the future.

The most widely used “textbook” at the time is The New England Primer, first published around 1690. It is based on The Protestant Tutor, and is used by the Puritans to teach various scriptural lessons to children, often via rote memorization of sayings or prayers.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.

Indeed, the motivation behind much education in the colonial is religious in character. If the path to eternal salvation lies in the Bible, one must be able to read “the good book” in order to embrace its wisdoms.

The Primer is joined in 1785 by a collection called A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. This three volume work is written and published by Noah Webster. He graduates from Yale and takes up teaching to earn a living, an experience that leads to his lifelong interest in advancing the science of pedagogy.

The heart of Webster’s compendium is the “Blue Backed Speller,” so-called for its binding, which is used for over a century to teach children the alphabet, key words, pronunciation and reading. It is accompanied by a “reader,” intentionally non-religious, featuring historians like Plutarch to poets like Shakespeare and political essayists like Addison and Swift. Its purpose according to Webster lies in:

Diffusing the principles of virtue and patriotism.

Actual data on literacy rates in early America do not exist, so historians have tried to piece together various clues from contemporary documents. From this work, it seems likely that upwards of 90% of all men were able to sign their own names when need be. The rate for women is thought to be lower.

The ability to read, as opposed to forming letters and writing one’s name, is a different matter. The two disciplines are taught separately, and reading skills are less common.

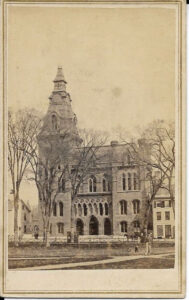

By 1790, “higher education” is beginning to take hold, with most universities started by, or affiliated with, one Christian church sect or another.

America’s Earliest Colleges And Their Religious Affiliations

| Original Name | Later | Founded | Colony | Religious Link |

| New College | Harvard | 1636 | Mass | Puritan/Cong. |

| College of William & Mary | William & Mary | 1693 | Virginia | Church of England |

| King William’s School | St. Johns | 1696 | Maryland | Freemasons |

| Collegiate School | Yale | 1701 | Conn | Puritan/Cong. |

| Bethlehem Female Seminary | Moravian College | 1742 | Penn | Moravian/Hussians |

| University of Delaware | Delaware | 1743 | Delaware | Presbyterian (Old) |

| College of New Jersey | Princeton | 1746 | New Jersey | Presbyterian (Free) |

| King’s College | Columbia | 1754 | New York | Church of England |

| College of Pennsylvania | Penn | 1755 | Penn | Church of England |

| College of Rhode Island | Brown | 1764 | Rhode Island | Baptist |

| Queen’s College | Rutgers | 1766 | New Jersey | Dutch Reformed |

| Dartmouth College | Dartmouth | 1769 | NH | Congregationalist |

| College of Charleston | Charleston | 1770 | So. Carolina | Church of England |

| Salem College | Salem | 1772 | No. Carolina | Moravian/Hussites |

| Dickinson College | Dickinson | 1773 | Penn | — |

| Hampden-Sydney Academy | Hampden-Sydney | 1775 | Virginia | Presbyterian |

| Transylvania University | Transylvania | 1780 | Virginia | Episcopalians |

| Washington & Jefferson | Washington & Jeff | 1781 | Penn | Presbyterian |

| University of Georgia | Georgia | 1785 | Georgia | — |

Relatively few Americans ever reach these colleges. Those who do are typically born into the upper classes, to parents who themselves are highly educated.

These children of privilege are tutored at home or at boarding schools, where they are exposed to a classical curriculum, straight out of European academies. Around the age of sixteen they enroll at college, completing their degrees four years late, and then transitioning into careers ordained for their class.

At the same time, there are exceptions to the rule who tell a uniquely American narrative. These are the “self-taught” men and women who rise to fame and fortune from humble roots. Their education is often a matter of happenstance – youthful access to a book or a teacher that sparks their curiosity, leads on to an insatiable quest for knowledge, and ends with intellectual powers and accomplishments that transport them up the social ladder.

They demonstrate the great “leveling effects” made possible in America through access to education. Soon enough, those “to the manor born” leaders like Jefferson and Madison, will be joined center stage by “log cabin” men such as Jackson and Lincoln

The interim from 1790 to 1820 finds only modest progress in the formal education of more children.

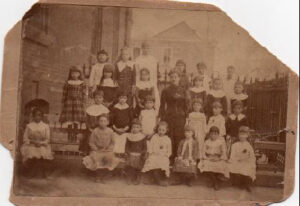

New England remains the bastion of childhood education based on its staunchly Puritan heritage. It becomes the model for “grammar schools,” open to the public, albeit with optional, not mandatory, attendance. These facilities are all privately owned until 1821, when the first government run “public school” appears in Boston.

The odds of getting some formal education go up for children living in towns and cities where “one room schoolhouses” become commonplace. But nine in ten children still reside on farms in 1820 — and for their parents, learning is probably a luxury relegated to second place behind farming duties and household chores.

Despite all this, the trend line on literacy and general education is probably tilting upward at the time. This is in large part due to the growing availability of teachers, as university attendance and graduation rates expand. While the vast majority of these graduates are men, the teaching career is already beginning to attract women in search of options to traditional housewifery.

And suddenly, education becomes a vehicle for women to protest existing gender roles in America.

These roles are inherited from the British Common Law of “coverture” which requires all women who marry to transfer basic rights to their husbands. Included here are prohibitions on owning property, signing contracts, participating in business or politics or serving in public office. Coverture also comes with a code of “proper behavior” for married women requiring outward piety, modesty, appropriate dress and manners and strict obedience to their spouse.

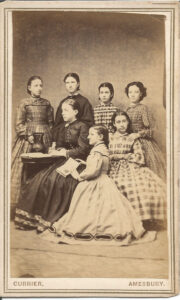

During The Second Great Awakening of the 1820’s and 1830’s coverture is challenged by a small corps of women who believe that higher education will be the path to their “freedom and equality.” They set out to replace traditional “finishing schools,” which teach etiquette and household duties, with colleges where women study the same curricula as their male counterparts.

Three women lead the way, the first being Emma Willard. She is a precocious child, sixteenth in line among her farming family in Berlin, Connecticut. In 1802, at age fifteen, she finally enrolls in a formal school, tears through the curriculum, and is hired as a teacher there at seventeen. After a short stint as principal of a female seminary in Vermont, she marries and opens a boarding school of her own in 1814. From then on her goal is to offer women students the same kind of rigorous educational experiences historically limited to men. As she later says:

We too are primary existences…not the satellites of men.

Her efforts to receive public funding for such a venture are met by resistance from legislators who argue that women don’t need higher education to perform their allotted role in society. But Willard persists and in September 1821, opens her Troy Female Seminary, the first school in America to offer a higher education degree to women. By 1831 the college is thriving, with some 300 students, mostly from wealthier families. Willard is also a prolific author, publishing books that range from American history to biology, geography and poetry. She turns leadership of Troy over to her son and his wife in 1838 and spends the rest of her life traveling, writing and speaking on behalf of education for women. After her death in 1870, Troy will be renamed The Emma Willard School in her honor.

Unlike Willard, Catharine Beecher grows up in a prominent and highly educated family. Her father is Lyman Beecher, graduate of Yale Divinity School, and the fiery Calvinist minister of a Congregationalist church in Litchfield, Connecticut, where Catharine, her sister, Harriet Beecher (Stowe), and twelve other siblings, grow up.

After her mother dies suddenly she is called upon, at age sixteen, to take over domestic duties for her family. From there she concludes that to accomplish their God-given role as homemakers, women must become better educated themselves so they can, in turn, educate their children. As she says:

Woman’s great mission is to train immature, weak, and ignorant creatures to obey the laws of God; the physical, the intellectual, the social, and the moral.

When her fiancée dies at sea, she throws herself into founding a series of academies to educate women. The curriculum emphasizes mastery of mathematics, theology and philosophy, and she develops her own textbooks and materials for use in the classroom. Later in life she founds the American Women’s Educational Association and promotes the idea that females by nature make the best teachers.

A third pioneer is Mary Lyon, born in Massachusetts in 1797, who makes her way to Byfield Seminary in 1821 and then dedicates her life to educating young women, especially those held back by poverty.

Lyon opens her Mount Holyoke with its first class of fifty young women on November 8, 1837. Lyon sums up her core principles as follows:

- Intellectual pursuits should be aligned with moral purpose.

- Tuition must be affordable to those with modest means.

- To help defray costs, students will work to maintain the campus.

- Daily exercise will be mandatory to build healthy bodies as well as minds.

- The academic curriculum will rival that offered at universities for men.

- Seven courses in science and mathematics will be required for graduation.

- Science study will include hands-on laboratory experimentation.

Her classical curriculum that sets the standard followed later by The Western College For Women (1855), Vassar (1861) and Wellesley (1870).

Owing in large part to Willard, Beecher and Lyon, young women are henceforth able to add teaching to nursing as a viable path to enjoying a paid career. Their efforts also prepares a next generation of women to lead the crusade for female rights.

Another early educational reformer is Bronson Alcott, a self-made Bostonian who begins as a traveling salesman before committing himself to challenging traditional teaching methods. Alcott is influenced by an 1801 book, How Gertrude Teaches Her Children, written by the Swiss reformer, Johann Pestalozzi, and focused on preparing students to think and to question, rather than simply to memorize material. To accomplish this, Alcott engages in “conversations” about the student’s experiences and beliefs, often related to their spiritual development and social issues.

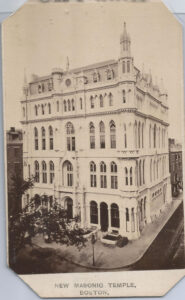

In 1834 he opens the Temple School at a Masonic Lodge in Boston. His assistants include Elizabeth Peabody, a pioneer in early childhood learning, and the women’s rights advocate, Margaret Fuller. Alcott decorates his classroom with paintings and sculpture, artifacts to prompt the Socratic dialogue he seeks. While his school closes owing in large part to his outspoken support for abolition and admission of a black student, he advances the shift from memorization to critical thinking. (His daughter, Louisa Mae Alcott, later earns fame for her novel Little Women and for her stand against slavery and for women’s rights.)

Starting in 1836 and lasting for more than a century, schoolchildren across America achieve literacy with the aid of a series of six graded textbooks known as “McGuffey’s Readers.”

The principal author of these works is William Holmes McGuffey, who earns a certificate to act as a “roving teacher” at fourteen before graduating from Washington College in 1828. His early experiences are frustrating, first with 48 students aged 6 to 21 in Calcutta, Ohio, and then in Paris, Kentucky where his classes are held in a retired smokehouse, using the Bible as his primary textbook. As a Presbyterian Calvinist, his conviction is that the driving purpose behind learning to read is to be able to explore the Scriptures and embrace the values they profess.

McGuffey joins the faculty of Miami University in Ohio, and is approached in 1835 by the Truman & Smith publishing company to author the six soon to be famous “Readers” that bear his name. He is convinced that young children are drawn into reading through exposure to stories which fascinate them and follow-up questions that engage their intellects. Thus his Level 1 “Eclectic Primer” offers simple tales that a teacher reads out loud and then breaks down into letters, sounds and words, all associated with pictures. After this establishes a primitive vocabulary – “boy, girl, farm, hen, run…” – the stories graduate into greater complexity, up to Level 6 which includes poems, essays and other narratives, often drawn from authors such as Milton, Byron and others. Over 122 million copies of McGuffeys Readers are sold over time.

Educational reforms pick up in the 1840’s as farming begins to give way to a diversified industrial economy based in towns and cities. This opens many new lucrative jobs that rely on brainwork rather than muscle power — ranging from modest clerkships to highly paid “professional” positions, such as lawyers, judges, clergymen, doctors and politicians.

Once more adults gravitate toward these jobs to earn a living, the need to deliver better education to more children becomes obvious.

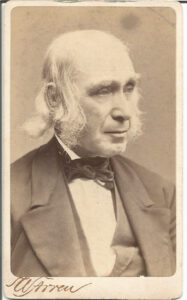

Leading the way here is Horace Mann whose early education as an impoverished youth consists of emersion in books from his local library. He then enrolls at Brown University in 1816 and graduates in three years at the top of his class. Mann teaches Latin and Greek at Brown before attending the famous Tapping Read Law School and setting up his own legal practice. He is then elected to the state legislature, and in 1837 is chosen to become Secretary of the Massachusetts’s Board of Education.

Mann begins by visiting a host of state schools and issuing a dismal report on conditions:

- Statewide there were roughly 3,000 common schools serving 165,000 students.

- Another 12,000 upper class students were attending private schools.

- The gap in educational quality between the private and public schools was obvious.

- Pedagogy in common schools was marked by rote memorization, enforced by the rod.

- Calling out individual letters and then saying the word aloud was the norm exercise.

- But the vast majority of students were unable to explain the meaning of words memorized.

He then sets out to shift the way reading is taught by bringing the words to life in associated pictures and sentences related to the student’s everyday life experiences. This one methodological change has a huge effect on reading comprehension and on everyday fluency.

In 1838 Mann launches The Common School Journal where he proposes a series of principles that will underlie the development of public education in America:

- The nation is well served morally and economically by a truly educated general public.

- Common schools should be paid for from public funds.

- Attendance should include children from all backgrounds and economic situations.

- Well-trained professional teachers are necessary to quality education.

- The curriculum should be broadened beyond the 3R’s.

- Content should be secular in character, while inculcating Christian moral standards.

- Harsh corporal punishment should be abandoned.

- All children (both sexes) should stay in school up to the age of sixteen.

- School buildings should be upgraded along with teacher pay.

In 1843 Mann’s search for educational advances takes him to Europe, where he embraces the so-called “Prussian model,” which starts with mandatory kindergarten and progresses to eight grades of Volksschule, four of Hauptschule (for 14-17 year olds) and then, for top students, universities.

This approach takes hold across America in the years ahead and secures his title as “father of America’s public schools.”

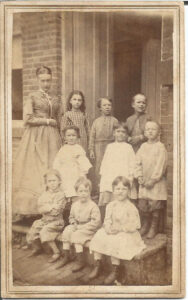

Finally, access to formal education for black people is essentially non-existent up to the Civil War.

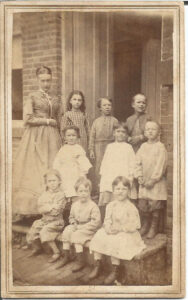

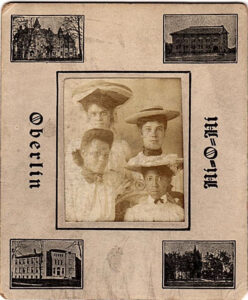

In the North, a few initiatives appear from time to time mostly in the northeast and mostly short-lived. A private school for black children surfaces in Boston in 1798; various African Methodist Episcopalian (AME) churches offer Sunday schools in the 1830’s; the Canterbury School admits black children in Connecticut before being shut down by angry neighbors; Oberlin Collegiate Institute admits its first black student in 1835 amidst much controversy; the Miner Normal School For Colored Girls opens in DC dedicated to training teachers. But racial prejudices throughout the region limit the impact and reach of these programs.

Meanwhile the South violently opposes educating black people, and passes laws to forbid it

South Carolina leads the way with a 1740 statute against teaching blacks to read or write, and others follow this precedent in the decades ahead.

The driving force behind this ban is fear – fear that literacy for slaves will result in bloody uprisings. As Elias B. Campbell, the well-known Washington lawyer and advocate of “colonization” puts it around 1817:

The more you improve the condition of these people, the more you cultivate their minds,

the more miserable you make them, in their present state. You give them a higher relish

for those privilegies which they can never attain, and turn what we intend for a blessing

slavery] into a curse. No, if they must remain in their present situation, keep them in the lowest state of

degradation and ignorance.

What education exists for black people comes by way of church Sunday schools or a smattering of well-intentioned whites. But even this much support is suppressed in the South after Nat Turner – who is known to read and write – leads his bloody 1831 rebellion in Virginia. All “colored schools” are prohibited across the region, along with the import of abolitionist newspapers. Alabama establishes $250 fines for teaching blacks, and Mississippi goes further, demanding that free blacks, likely more literate, leave the state for good.

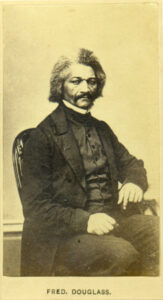

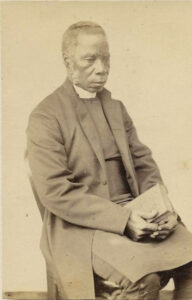

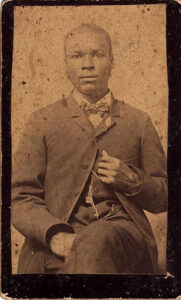

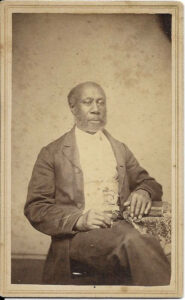

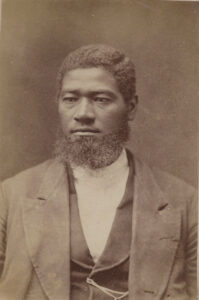

Despite these efforts at mind control, intellectually gifted black continue to surface after having been tutored when young. In Boston, the enslaved 17 year old Phyllis Wheatley shocks the public in 1773 with her lyrical poetry. The African Masonic Lodges founded by Prince Hall around 1785 advance the cause of education. At the turn of the century preachers such as Absalom Jones and Richard Allen in Philadelphia and Thomas Paul offer their stirring sermons. Then come the highly articulate pamphlets and lectures of freedman David Walker in 1829, and the two run-away slaves, Frederick Douglass and Henry Highland Garnet, all demonstrating the power of education of black people.

But progress toward educating the black population remains tragically slow even after the Civil War when slavery ends and they become American citizens.