Section #11 - Other Military Conflicts

The Boer War: October 11, 1899 – May 31, 1902

South Africa is settled by the Dutch East India Company in 1652. The indigenous population at the time comprises four African tribes, the largest being the Zulus. The Dutch enslave some of the natives and hire others to build their settlements. The language that develops is called Afrikaans, a blend of the Dutch and Zulu tongues.

In 1806, Britain rests control of the Cape Colony at the southern tip of Africa from the original Dutch settlers. Tensions between the two groups of settlers rise in the 1830’s when Britain declares English as the official language of the land and abolishes slavery. This leads to the “Great Trek” movement to the north by the Dutch – known as Boers (“farmers”) — and their founding of two independent nations: The South African Republic and the Orange Free State.

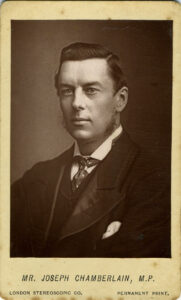

The British respond with repeated efforts to annex the Dutch enclaves. Their first attempt in 1848 fails. They try again unsuccessfully in what becomes the First Boer War of 1880-81. Then gold is discovered near the Orange Free State town of Witwatersrand in 1886 and English “Uitlanders” (Outlanders) filtering into the fields meet armed resistance from the locals. Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain responds by appointing the outspoken imperialist, Sir Alfred Milner, as High British Commissioner and the Boers elect their equally adamant defender, Paul Kruger, as President of the SAR. These moves signal the coming of open warfare.

The tipping point occurs on October 9, 1899, when Kruger demands that all British troops stationed in and around the Dutch borders be withdrawn. The ultimatum is rejected and the Second Boer War gets under way with commanders General Sir Redvers Buller leading Britain’s forces and Piet Joubert those of the SAR.

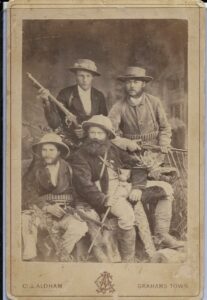

The Boer War plays out in two phases: a conventional conflict which runs until November 1900, followed by another 17 months of intense guerrilla fighting leading up to the peace Treaty of Vereeniging signed on May 21, 1902. Over that span, Britain will deploy some 500,000 men into the field, while the Boers are able to muster roughly 88,000.

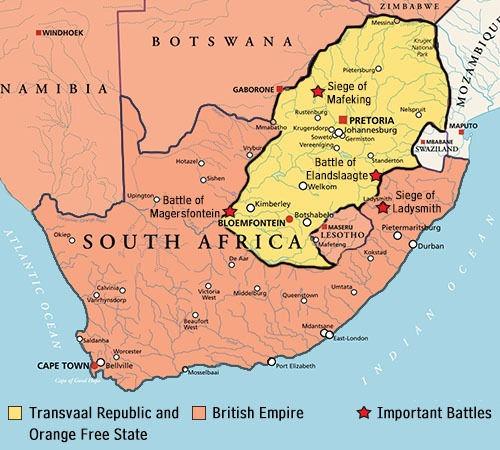

The Boers, however, have mastered their rugged landscape and employ hit and run tactics to frustrate the British history and wish to fight set-piece battles. Surprise is also a part of the Boer arsenal and they quickly display it by going on the offensive, laying sieges in the North at Mafeking on October 13, 1899, in the south at Kimberley on October 15, and finally on November 2 at Ladysmith, home of the DeBeers diamond mines owned by Cecil Rhodes.

Efforts to relieve these three siege sites become central to British strategy.

Their Ladysmith campaign lasts for 118 days, with Rhodes insisting that it must be the top priority. The campaign begins with a critical loss on December 15, 1899 at the Battle of Colonso. The victor there is the skilled Boer commander, Louis Botha, who has succeeded an invalided Piet Joubert. After the setback, Redvers Buller signals the British General George White to surrender the garrison at Ladysmith. White refuses with the immortal line: “I hold Ladysmith for the Queen.” And indeed he does. A Boer attack is repulsed three weeks later at Platrand, and on February 27, 1900, the siege is lifted.

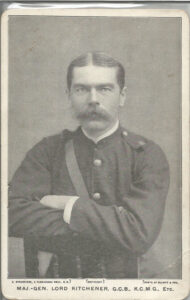

The town of Kimberly lies 360 miles due west of Ladysmith, and its rescue is initially in the hands of General Paul Methune. He wins the Battle of Modder River in late November, but then blunders badly at Magersfontein, suffering nearly 1,000 casualties. That defeat, coupled with costly losses at Colonso and Stormberg, leads to the sacking of Redvers Buller. He is replaced by the duo of Lord Frederick Roberts and Herbert Kitchener. Together they achieve the decisive victory at Paardeberg Drift over General Piet Cronje that frees Kimberly on February 27, 1900.

The British then turn their eyes east toward Bloemfontein, capital of the Orange Free State. President Paul Kruger arrives to rally the burghers, but Robert’s forces are overwhelming. The clever Christiaan de Wet fights a rear-guard action to slow the British, but on March 10, 1900, Bloemfontein surrenders. Some 50,000 troops pour into the town and they are joined by High Commissioner Milner to celebrate the victory.

On May 3 the main body of Roberts’ forces head northeast some 300 miles to assault the Boer’s other capital. As they depart the strains of “We are marching to Pretoria” becomes the popular melody of the day.

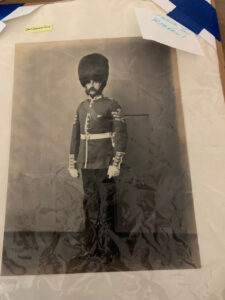

Meanwhile, near Pretoria, the siege of Mafeking, continues for 217 days with a tiny garrison of 1500 British troops under one Robert Baden-Powell holding out against some 8,000 Boers. Baden-Powell employs guile and tenacity to frustrate the Boers until a British column of 2,000 men under Colonel B.T. McMahon breaks through on May 17, 1900. For his efforts at Mafeking, Baden-Powell is praised by Queen Victoria and becomes an overnight hero across Britain.

On May 31, 1900, Roberts’ grand army reaches Johannesburg, 45 miles south of Pretoria, and on May 28 Britain announces that it is annexing the Orange Free State and the Witwatersrand gold fields. The Boer commanders meet with Paul Kruger in Pretoria, knowing they cannot defend the capital with the meager 7,000 troops left. Talk of an absolute surrender is discussed, but the decision is to leave the city and buy time by heading toward the eastern grasslands (the “Veldt.” Roberts then makes his triumphal march into Pretoria on June 5.

Generals Botha and De la Rey attempt to slow down the British pursuit with a defense line east of the city, but Lt. General Ian Hamilton and General John French overrun it at the battle of Diamond Hill on June 12, 1900.

While the fall of Pretoria appears to end the war, the “bitter-ender” Boers who flee east will extend the bloodshed for another two years.

In November 1900, Lord Roberts returns to England and receives an earldom and L100,000 for his successes. He turns command of the South African army over to Herbert Kitchener who is charged with rooting out all remnants of the remaining Boer rebels. But the task is not an easy one, with commando raids led by Christiaan de Wet and Jacobus de la Rey harassing British army bases and maintaining control over many areas of the Veldt. A southern raid by Jan Smuts actually comes within 50 miles of Capetown.

A frustrated Kitchener reacts by burning Boer farms and locking up suspicious families in concentration camps, where several thousand die of hunger and disease. Finally the remaining Boer leaders – Botha and Smuts in particular – convince the resisters to give in. The result being the Treaty of Vereeniging which ends the conflict on May 31, 1902.

Eight years later, the Union of South Africa becomes official, with a total of 5,175,000 residents, 21% white and 79% black, and a government policy of apartheid. Ironically its first Prime Minister is none other than the Boer Louis Botha.