Section #13 - Propensity for Violence

Our Propensity for Violence

You are there:

while America becomes a nation of laws it also becomes a nation with a propensity to rely on violence to resolve its conflicts.

“Why” this becomes a norm remains a mystery. Those departing England for the new world seek a “shining city on a hill,” not another battleground. But once here, their first 200 years of history are anything but peaceful.

“How” violence becomes a part of American culture is more readily understood.

Fear is one precursor to violence and the battles for global hegemony between Britain, France and Spain force the colonists into combat mode in order to survive. Then comes the first war against the Crown, fought under the bellicose banners of “strike the first blow,” and “give me liberty or give me death.”

But even independence does not insure security, and the new United States remains surrounded by the British in Canada and by Napoleonic France and Spain to the south and west. Despite these dangers, concerns about internal tyranny prohibit the creation of a standing army of trained professional soldiers. Instead individual citizens are mandated to store weapons of war in their homes and to serve in local militias.

As Thomas Jefferson says:

The Constitution of most of our states (and of the United States) assert that all power is

inherent in the people; that they may exercise it by themselves; that it is their right and

duty to be at all times armed.

Possession of firearms in civilian hands thus becomes ubiquitous – and using them to resolve disputes follows on.

One symbol lies in dueling, a custom brought along from Europe and practiced with alarming rates and dire consequences.

Here an individual who perceives a “slight” issues a formal challenge to an adversary to engage in a duel. Intermediaries for both sides step in to cool tempers and, in roughly 80% of the cases they succeed. But if not, the two parties retreat to a “field of honour” seeking satisfaction.

The confrontation is choreographed according to a set of rules known as the Irish Code Duello. A time and meeting place are selected, along with the weapons chosen by the challenged party. Single shot pistols replace swords as the norm, although advantages are at times sought by resorting to rifles or even Bowie knives. Seconds, including a doctor, are present to arrange the ground, insure that the rules are followed, care for injuries, and carry a will to the next of kin if necessary.

Where pistols are used, the two combatants stand roughly ten feet apart facing each other, albeit turned slightly to narrow their profile, especially their chests. They raise and point their weapons, and when a designated second shouts “present,” they are free to fire at will. At times one man will fire before the other, and then he is required to hold his posture while the opponent takes his shot.

The initial discharges may end with neither man hit or with one or both hit or even killed. But assuming the challenger is still alive, it is up to him to call an end or to insist on a second round. A third round may also occur, but that is the limit set for “civilized behavior.” Before additional rounds, the seconds try their best to end the affair, arguing that both men have already defended their honor.

Nobody knows how many duels are fought over the years. But the more famous ones – those involving public figures – are recorded at the time. Some fifty of these are shown below.

Perhaps the most memorable duel of all occurs in 1804 when America’s sitting Vice-president, Aaron Burr, challenges Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, and mortally wounds him with a shot to the hip. Ironically the pistol Hamilton chooses is the same one used by his son Philip when he is killed on the same field three years earlier.

President Andrew Jackson is rumored to have engaged in scores of duels, including one in 1806 that leaves his opponent Charles Dickinson dead and the General with a slug that remains lodged too near his heart to be removed and that continuously plagues his health.

Jackson’s bete noir, Henry Clay exhibits a comparable temper with multiple duels, one involving Congressman Humphrey Marshall of Kentucky that ends with both men wounded.

Senator Thomas Hart Benton duels twice with Charles Lucas, killing him on the second occasion.

The rising naval star Commodore Stephen Decatur, a hero in the War of 1812, is killed by Commodore James Barron who is offended by Decatur’s criticism of his conduct in the 1807 Chesapeake-Leopold engagement.

Other public figures known for their frequent recourse to dueling include the Texan, Sam Houston, and several of the so-called Fire-Eater southern secessionists, Henry Foote, Preston Brooks, George McDuffie and Louis T. Wigfall.

Famous Duels Involving Public Officials

| Year | First Duelist | Opponent |

| 1777 | Button Gwinnet (w) | General Lachlan McIntosh (w) |

| 1778 | General Charles Lee (w) | Fellow officer John Laurens -SC |

| 1780 | James Jackson | George Wells (k) |

| 1788 | Andrew Jackson | Waightstill Avery |

| 1801 | John Rowan | James Chambers (k) |

| 1801 | Philip Hamilton (k) | George Eacker NY lawyer |

| 1802 | Richard Spaight (k) | John Stanly |

| 1803 | John Ward Gurley (k) | Philip Jones |

| 1803 | Andrew Jackson | John Sevier |

| 1804 | Alexander Hamilton (k) | Aaron Burr |

| 1806 | Andrew Jackson (w) | Charles Dickinson (k) |

| 1807 | William C.C. Claiborne (w) | Daniel Clark |

| 1809 | Henry Clay (w) | Humphrey Marshall (w) |

| 1810 | John G. Jackson (w) | Joseph Pearson |

| 1813 | Andrew Jackson (w) | Thomas Hart Benton |

| 1817 | Thomas Hart Benton (w) | Charles Lucas (w) |

| 1817 | Thomas Hart Benton | Charles Lucas (k) |

| 1819 | John M. McCarty (k) | Armistead T. Mason (k) |

| 1820 | Stephen Decatur, Jr. (k) | James Barron (w) |

| 1823 | Clement Clay | Dr. Waddy Tate |

| 1823 | Joshua Barton (k) | Thomas Rector |

| 1823 | Andrew Scott | Judge Joseph Selden (k) |

| 1826 | Henry Clay | John Randolph of Roanoke |

| 1826 | Sam Houston | William White (w) |

| 1827 | Henry Conway (k) | Robert Crittenden |

| 1827 | Robert Vance (k) | Samuel Carson |

| 1827 | George McDuffie (w) | William Cumming |

| 1828 | George Crawford | Thomas Burnside (k) |

| 1829 | Henry Foote (w) | Edmund Winston (w) |

| 1831 | Spencer Pettis (k) | Thomas Biddle (k) |

| 1832 | Thomas Baltzell | James Westcott (w) |

| 1832 | Benjamin Perry | Tyler Bynum (k) |

| 1832 | Philip Minis | James Stark (k) |

| 1837 | A. S. Johnston (w) | Felix Huston |

| 1838 | Johnathon Cilley (k) | William Graves |

| 1838 | Preston Brooks (w) | Louis Wigfall |

| 1839 | Leigh Read | Augustus Alston (k) |

| 1839 | August Belmont (w) | Edward Hayward (w) |

| 1840 | Louis Wigfall | Thomas Bird (k) |

| 1843 | George Waggaman (k) | Dennis Prieur |

| 1845 | William Yancey | Thomas Clingman |

| 1847 | Albert Pike | John Roane |

| 1852 | James Denver | Edward Gilbert (k) |

| 1852 | John McDougal | A.C. Russell (w) |

| 1852 | Felix Zollifcoffer | John L. Martin |

| 1853 | Samuel Inge | Ed Stanly |

| 1853 | William Gwin | J.W. McCorkel |

| 1856 | Gratz Brown (w) | Thomas Reynolds |

| 1859 | David Terry | David Broderick |

But the propensity for violence in America extends far beyond personal dueling.

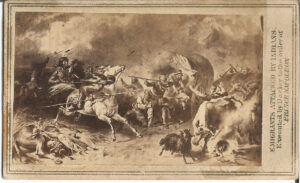

Government sponsored attacks are repeatedly directed at members of Native American tribes who are forcefully driven off their historical homelands by white settlers. These conflicts begin during the colonial period and range from New England to the Carolinas and west to the Great Lakes region.

Early Conflicts Between Colonists And Tribes

| Year | Belligerants | Outcome | |

| 1636-38 | Pequot War in Connecticut Valley | Mass. Bay colonists vs. Pequot tribe | Pequot tribe disbanded for good and survivors sold into slavery |

| 1675-78 | King Philips War in New England | Colonists vs. King Philip, Wampanoags sachem | Tribe defeated and Philip killed at Mt Hope, Rhode Island |

| 1711-15 | Tuscarora War in North Carolina | Colonists vs. Tuscarora, part of Iroquois nation | Colonists win and surviving Tuscarora migrate north to New York |

| 176-66 | Pontiac’s War near Niagara Falls | Chief Pontiac confederation vs. British colonials | Stalemate with 8 forts destroyed and British adjusting policies with tribes |

| 1774 | Lord Dunmore’s War in Virginia | Virginia Governor Dunmore’s vs. Shawnee and Mingos | Virginia victory at the battle of Mount Pleasant for Dunmore v |

When the Revolutionary War breaks out, tribes are forced to choose sides. The large majority back the British who have long supported their fur-trading operations in the north and have refrained from attempts to confiscate their homelands.

A few northern tribes, notably the Oneida, Mohicans and Delaware, favor the Americans, while the powerful Iroquois are divided in their loyalties.

It remains unclear whether the tribal alliances are decisive in the outcome of any given battle. But it’s obvious that the British are advantaged by their native support.

Tribal Alignments During The Revolutionary War

| Allied With Americans | Where |

| Passamaquoddy | Massachusetts |

| Stockbridge-Mohican | Massachusetts |

| Delaware/Lenape | Ohio Valley |

| Iroquois (Tuscaroras, Oneidas) | New York, Canada |

| Potawami, | Great Lakes region |

| Catawaba | The Carolinas |

| Allied With Britain | |

| Shawnee | Ohio Valley |

| Miami | Great Lakes region |

| Huron | Great Lakes region |

| Iroquois (Mohawk, Seneca, Cuyugas, Onandogas) | New York, Canada |

| Chickasaw | Mississippi, Alabama |

| Choctaw | Mississippi |

| Cherokee | Georgia, Carolinas |

| Neutral/Divided | |

| Creek | Florida, Georgia |

| Abenaki | New England |

The Revolutionary War proves disastrous for the tribes in general, but particularly for those who side with Britain. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris officially ending the war, the British cede almost all of the land occupied by the tribes to the Americans. Beyond that, the war erodes most of the good will many Americans initially feel for those who “were here first.”

Over the next half century, violent aggression against the Native Americans is ongoing, with a series of landmark battles ending in forced treaties and massive land cessions. These are interrupted from time to time by tribal leaders like the Shawnee’s Blue Turtle and Tecumseh who form confederations and record short-lived victories. But eventually resistance is ground down, and after the Indian Removal Act of 1830 passes in Congress, the eastern tribes are all driven west along the Trail of Tears to reservations in Oklahoma.

Some Later Conflicts Between The U.S. Military And Various Tribes

| Year | Key Battle | Outcome | |

| 1787 | Battle of the Wabash in eastern Indiana | Confederacy of Shawnee Blue Jacket, Miami Little Turtle, Lenape and Ottawa plus British support | General St. Clair suffers worst loss to tribes in American history with over 600 U.S. troops killed. This is a major wake-up call for the U.S. military. |

| 1794 | Battle of Fallen Timbers near Maumee. Ohio | Shawnee confederacy but now without British support | Mad Anthony Wayne defeats Blue Jacket followed by Treaty of Greenville ceding Ohio territory |

| 1813 | Battle of the Thames – west side of Lake Erie | British plus Shawnees, led by Tecumseh | William Henry Harrison gains national fame here and Tecumseh is killed. |

| 1814 | Battle of Horseshoe Bend in eastern Mississippi | Red Stick Creeks | Andrew Jackson with Cherokee and Choctaw support crush the Creeks |

| 1818 | First Seminole War in Florida | Seminoles (Creek links) and run-away slaves | US wins lead to Spain ceding Florida to America |

| 1823 | Arikara War in South Dakota | Arikara tribe | Stand-off between U.S. Army and the Arikari |

| 1832 | Blackhawk War in Illinois and Wisconsis | Sauks, Meskwakis and Kickapoos led by Chief Blackhawk | Tribal raids to reclaim “ceded land” results in a victory at Stillman’s Run and a defeat at Wisconsin Heights. Both Lincoln and Jeff Davis serve in the US militia here, but not in combat. |

| 1830-1847 | Indian Removal Act | The “Five Civilized Tribes” of the southeast: Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw and Seminole | U.S. Army drives the tribes from their homelands to “reservations” mostly in Oklahoma; known as “Trail of Tears.” |

| 1835-1842 | Second Seminole War in Florida | Seminoles led by Chief Oceola | Multiple U.S. Generals finally win with Oceola captured and dies in prison |

| 1840 | The Great Raid of 1840 in Texas | Commanches under Chief Buffalo Hump | Series of successful tribal raids on America’s Texian settlers |

Immigrants are another target of American violence.

Much of this traces back to Catholic-Protestant clashes in England, coupled with paranoid belief that immigrant Catholics will be loyal to the Pope in Rome rather than to their government in DC.

The antagonism toward Catholics is fairly muted until the 1840’s when the potato famine in Ireland and the failure of anti-monarchy movements in Germany and the surrounding duchies lead to a quantum jump in immigration to America.

Immigration Trends

| Total | Ireland | Germany | All-Other | |

| 1820-29 | 128,502 | 51,617 | 5,753 | 71,132 |

| 1830-39 | 538,381 | 170,675 | 124,726 | 242,980 |

| 1840-49 | 1,427,337 | 656,145 | 385,434 | 385,758 |

By 1850, the number of foreign born residents reaches 2.24 million or 9.7% of the total population – up from only 4.6% a decade earlier. Most of the immigrants end up in major cities in the North, and often inland from the east coast. Milwaukee, Chicago, St. Louis and Cincinnati all have foreign born representation in the 50% plus range as of 1850.

In addition to concerns about “patriotism,” the Irish are portrayed as ignorant, prone to crime, and the source of cheap labor undercutting wages for others at the low end of the scale. The German immigrants are a different matter, mostly trained artisans, but also political rabble rousers and thought to be sure fire Jacksonian Democrats.

The organized backlash against the immigrants originates in Philadelphia in 1844, the brainchild of a Jewish-turned-Methodist preacher, Lewis Levin, who is convinced that a conspiracy is under way to threaten the nation’s values and government. His “Native American Party” calls upon U.S.- born, white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants to “take back the country” – and anti-Catholic riots break out in Philadelphia and Louisville. But the Mexican War soon diverts the nation’s attention and Levin fades from sight.

The movement is reborn however with the dramatic uptick in immigration. First as the “Order of the Star-Spangled Banner,” and then, by 1852, as the “Native American Party” – nicknamed the “Know Nothings” for its member’s rehearsed response to inquiries about its operations.

The most violent attacks on immigrants occur in Philadelphia and Louisville, both strongholds of the Know Nothings Party.

Major Incidents Of Anti-Immigrant Violence

| Year | Where | What |

| 1844 | Philadelphia, around Kensington | Demand for use of Catholic Bible in school leads to mob action with two killed and Catholic churches and seminary burned. |

| 1844 | Philadelphia, aroundSouthwark | After weapons are stored in a Catholic Church, a large mob demands their removal. The militia complies but then they are attacked for appearing to protect the church. Both sides employ canon fire and rifles and four militia and twelve rioters are left dead. A larger contingent of militia arrive to restore order. |

| 1855 | Louisville, Kentucky | Catholic opposition to the King James Bible, oath taking and other affirmations of loyalty leads to the formation of pro and anti- Nativist lodges and a “Bloody Monday” clash with homes and churches burned and over twenty persons killed. |

The Know Nothings achieve enough scale in 1852 to nominate a presidential candidate, Daniel Webster, but he dies nine days before the election. Still by 1855 the party becomes a national force, winning the Speaker of the House post after 133 ballots for Nathaniel Banks in the 34th Congress. This, however, is its high water mark, as dissension over slavery divides the party and drowns out a focus on immigration.

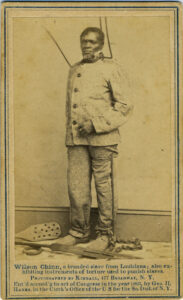

Chattel slavery then emerges as the enduring symbol of America’s propensity for violence.

Its roots are planted deep in the most sinister aspects of human nature:

* The tribal instinct to sort people into the superior Us vs. the inferior Other;

* A twisted satisfaction from asserting control and power over this Other;

* The use of physical and psychological force to maintain the dominance;

* An accompanying fear that the victim of this abuse will seek retribution;

* Followed by an ever increasing set of punishments to prevent rebellion.

The “Others” in this case are kidnapped Africans who first appear in August 1619 when the private British ship White Lion drops anchor on the James River near Hampton, Virginia. In exchange for “victuals,” the ship commander hands over “20 and odd” Africans seized earlier in a raid on a Spanish slave ship.

Their “Otherhood” is readily apparent in the color of their skins, their facial contours, their hair, their obvious differences in dress, manners and customs. The colonists brand them as “negros” or “negras” from the Spanish for “black,” and the Latin word “niger.”

The question of what to do with the 20 slaves is resolved by turning them over to Sir George Yeardley, the sitting Governor of Virginia. Yeardley is the owner of a 1000 acre plantation on the James River and presumably he puts them right to work planting and harvesting his tobacco.

This kind of forced labor is long-standing practice in England. It begins with serfs whose survival depends on working land owned by the aristocracy. Later comes slavery, with some Africans working on the great domestic estates, others in British colonies, especially the West Indies. While the serfs are regarded as “full human beings,” the Africans are seen as a lower form of life.

As slavery expands in the colonies, some owners simply accept it while others feel compelled to try to rationalize it. Among the latter is Thomas Jefferson who concludes:

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race,

or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments

both of body and mind… This unfortunate difference of colour, and perhaps of faculty, is a

powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people.

Jefferson’s racial stereotyping is readily accepted across the South and North and it becomes codified in Article I, Section 2 of the 1787 Constitution:

Representation and direct taxes shall be apportioned…by adding the whole Number

of free Persons…and three fifths of all other Persons (i.e. those enslaved).

At this point, the Africans are officially classified as 3/5th of a “full human” and are reduced to chattel or personal property, akin to farm animals, and vulnerable to the whims of their owners.

In some cases they are treated favorably, albeit absent their personal freedom. But many other times, they are forced to endure what Joseph Conrad calls “the heart of darkness,” where…

The mind of man is capable of anything.

Frederick Douglass captures these moments in his autobiography:

There are certain secluded and out-of-the-way places, even in the state of Maryland,

seldom visited by a single ray of healthy public sentiment—where slavery, wrapt in its

own congenial, midnight darkness, can, and does, develop all its malign and shocking

characteristics; where it can be indecent without shame, cruel without shuddering, and

murderous without apprehension or fear of exposure.

My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read

departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery

closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!

What follows from this abuse is a cycle of terror that feeds upon itself and ends with violence suffered by the enslaved and their masters alike.

The slave fears the whip and the many other forms of degradation imposed upon him. At least sub-consciously the master identifies with the slave’s plight and begins to fear a moment of retaliation. In turn, to avoid the threat, he imposes even greater forms of punishment and control. As Jefferson puts it:

Slavery is like holding a wolf by the ears – one can neither safely

hold him, nor safely let him go.

For some captives, all hope is abandoned, and their pleas to “go home” are directed at the peace of the grave.

Oh yes, I want to go home…where dere’s no whips a crackin…I want to go home.

Swing low, sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home…to carry me home.

Others, perhaps 50,000 per year, attempt to run away, and some succeed either on their own or with help from the Underground Railroad.

A few decide to fight back in what are termed “black uprisings.” How often these occur is unknown, but five receive national coverage.

Five Significant Slave Uprisings

| Year | Where | Led By | Outcome |

| 1800 | Henrico County, Va. | Gabriel | Large-scale plot leaks, rebels intercepted by militia , 26 hanged including Gabriel. |

| 1805 | Chatham Manor, Va. | Handful of slaves | Cruel overseer Stark an four other whites are whipped before the end with two slaves dead |

| 1811 | German Coast, La. | Charles Deslondes | Band of 25 slaves hack Gilbert Andry to death and march toward New Orleans raiding plantations and growing to 200 strong. They lose a pitched battle with militia. Twenty blacks KIA, 50 captured, Deslondes butchered. Severed heads on pikes line the road to NO. |

| 1822 | Charleston, S.C. | Denmark Vesey | AME minister Vesey’s elaborate Bastille Day plan leaks and 67 conspirators are arrested and summarily hanged, including Vesey. |

| 1831 | Jerusalem, Va. | Nat Turner | The most vicious recorded uprising is led by 30 year old Nat Turner who reads the Bible and plots revenge for being whipped and having his wife sold off. His assault begins with 7 slaves using axes to kill men, women and children on his plantation before adding 70 followers who sack about 15 nearby farms and murder some 60 whites. Finally the state militia stops the band, hanging and beheading those captured including Turner. At his trial Turner prides himself on his actions saying they were justified by the suffering of slavery. |

Increased levels of white fear follow each of these “uprisings.” In the South, owners try to weed out and summarily lynch potential “trouble-makers.” In the North, white fear results in even more “black codes,” segregation and vicious race riots.

Northern Race Riots

| Year | City | Neighborhood | Outcome |

| 1824 | Providence, RI | Hardscrabble | White mobs roam the area and destroy upwards of 20 black homes. |

| 1829 | Cincinnati | 4th ward | Competition for low paying labor jobs leads roving Irish bands on a 5 day rampage to burn down African-American homes and businesses and caused about a half of all blacks to leave the city, with some heading to Canada. |

| 1831 | Providence, RI | Snowtown | A much larger riot lasting five days and nights with more destruction and at least one known death |

| 1834 | New York City | Five Points | The spark here is abolitionist minister Dr. Samuel Cox welcoming blacks into his church services. Black homes are destroyed before New York’s National Guard breaks up the chaos. |

| 1835 | Boston | Lecture hall | Abolitionist Lloyd Garrison is seized after attending an Anti-Slavery Society meeting, dragged through the streets by a rope by a white mob who threatens to hang him. Police save him and he spends the night in the jail for safety. |

| 1836 | Cincinnati | 1st and 4th wards | Angered by abolitionist James Birney and his newspaper, whites respond by throwing his presses into the Ohio River and again razing black residences and storefronts, while the Mayor applauded. |

| 1838 | Pennsylvania Hall | Philadelphia | Four days after the convention hall opens with an abolitionist conference, anti-black rioters burn it to the ground |

| 1851 | Pennsylvania | Lancaster County | Slave owner Edward Gorsuch is killed attempting to recapture his run-away slave after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 goes into effect. The slaves escape to Canada and the government fails to convict the protectors in a jury trial. |

The pattern of violence in the American culture is well established by 1840 – from the early global battles for survival to personal dueling; from brutality toward the native tribes and foreign immigrants to black uprisings, white retribution and race riots.

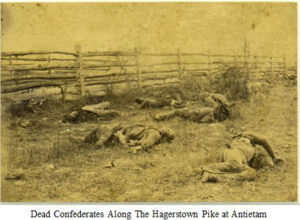

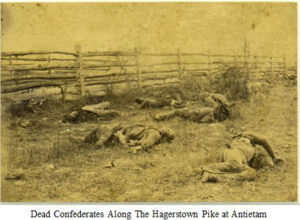

But these pales in comparison to the violence associated with the conflicts related to the nation’s original sin of slavery:

* The Mexican War of 1846-47 with military and civilian casualties estimated at roughly

* 13,000 on the American side and 25,000 for the Mexicans.

* The tragic events in “Bloody Kansas” between 1854 and 1858.

* The Civil War of 1861-65 with brothers fighting brothers and deaths across both sides

around 750,000 or over 2% of the total population at the time.

A southern preacher of a much later era sums up the toll of this American culture of violence.

The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral, begetting the very thing

it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may

murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence

you murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate…

Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night

already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate

cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. (Martin Luther King/1967)