Section #5 - Our Churches and Religions

Our Churches and Religions

You are there:

Many of those white men and women risking the journey across the Atlantic are animated by the prospect of freedom to follow their own religious paths to salvation.

One among them is the Puritan minister John Winthrop whose 1603 sermon sets out his vision for a better life in the new land:

Our posterity will be to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God…so the Lord will delight to dwell among us as his own people and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways. We shall than be as a City upon a Hill, with the eyes of all people upon us.

Starting from there, Americans will embrace the chance to challenge the old world religious traditions with the same zeal evident in arriving at their own forms of self-government.

The foundation for a large percent of the new arrivals is the Church of England which is familiarly known in America first as the Anglican and later as the Episcopalian Church. It is founded in 1527 by King Henry VIII after Pope Clement VI refuses to grant him a marriage annulment. Five colonies recognize this affiliation in their official charters: Virginia, New York, Maryland, North and South Carolina. The other eight do not.

What the outliers tend to have in common is resistance to the 1662 Act of Uniformity, whereby the Church of England dictates the rites and ceremonies required for membership, including adoption of the Book of Common Prayer, administration of the sacraments, and the episcopal ordination of all ministers. Those who refuse to comply are labelled “non-conformists,” among them certain Puritans, and others who ended up as Presbyterians, Baptists or Congregationalists.

In New England, the founding charters of Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Hampshire identify with the Congregational Church – while five other colonies opt against any formal church affiliation: New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Georgia.

But America is thoroughly Protestant into and beyond the colonial period – the only exceptions being Spain’s Catholic “missions” scattered from Florida west to New Orleans and up the Mississippi River. Very few Jews emigrate, with the only early synagogues in Rhode Island and New York.

Each of America’s early churches has its own unique characteristics.

The Anglican/Church of England is noted for its conservative governance, with authority over all church matters resting with it hierarchy of “epistates” or bishops. Its liturgy mimics the old world Catholic Mass, and its tonality is formal. Followers are heavily skewed toward the Southern colonies.

Other American churches are more sharply aligned with the German and Swiss contemporaries, Martin Luther (1483-1546) and John Calvin (1509-1564), who spark the original Protestant Reformation. Both regard the entrenched clergy of their time as corrupt, and encourage their followers to take control over their own church governance.

This principle is embedded in the Puritan flight from the Church of England, and it carries over to their practices in America. The Puritans and Lutherans tend to eventually evolve into the Congregational Church, which eliminates the clerical hierarchy and places authority for religious practices in the hands of the membership. Its influence is centered in New England.

Like the Congregationalists, Baptists embrace basic Calvinist tenets. What distinguishes them, however, is a belief that the act of baptism should be reserved for adults, not newborns, as a symbol of their studied commitment to entering the church. After its founding by Roger Williams in 1632, the Baptist Church spreads beyond Rhode Island, especially into the South.

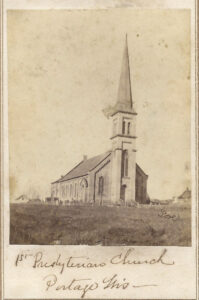

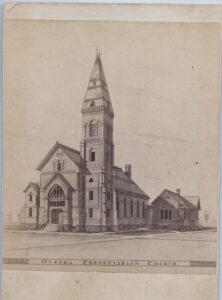

The Presbyterian sect, founded by the Scottish preacher, John Knox (1505-1572), also traces its theological roots to Calvin. Its governance, however, falls to a body of “church elders” rather than to the members as a whole. Hence its name, which derives from the Greek word for elders – “presbyteros.” The Presbyterian Church arrives in America around 1706, accompanying immigrants from Scotland. It takes hold in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and the western territories.

Other smaller sects include Quakers, Mennonites, Shakers and Amish, all tending to set up communities of fellow believers who distance themselves from societal distractions under the aegis of the Biblical warning, Keep thyself unspotted from the world.

The Quaker sect, or Society of Friends, in particular preaches a search for the “inner light” found in the Bible, which causes them to “tremble before the Word of God.” Their home is in Pennsylvania.

Just as each religious denomination is settling into place in the colonies around 1730, the Enlightenment spirit strikes the American church scene. Its general effect is to awaken individuals to the notion of self-reliance – that by using their own capacities of reason, they can re-shape their societies and personal religious destinies.

The Enlightenment sets off ongoing clerical debates often mooted at the nation’s earliest universities, all linked to a sponsor church:

American Universities Founded By Churches

| Name | Year | Church Affiliation |

| Harvard | 1636 | Congregationalist |

| William & Mary | 1693 | Church of England |

| Yale | 1701 | Congregationalist |

| Princeton | 1746 | Presbyterian |

| Columbia | 1754 | Church of England |

| Penn | 1757 | Anglican/Methodists |

| Brown | 1764 | Baptist |

| Rutgers | 1766 | Dutch Reformed |

| Dartmouth | 1769 | Congregationalist |

Soon enough these debates center on two opposed beliefs about the pathways to salvation:

* On one hand are the Calvinists, arguing that, while every person should strive to lead a

good life, eternal salvation is a matter of “pre-destination” with God alone deciding who

is fated to be among the “elect” and who will fall short.

* On the other hand, are the Arminians, named after the Dutch Reformed theologian, Jacob

Arminius (1560-1609), who believe that every man is blessed by a loving God with the

capacity to be saved, with the outcome determined by their own free will and actions.

A leading Calvinist proponent at the time is Jonathan Edwards, a precocious student who enters Yale at age 13 and graduates as valedictorian of his class in 1720. From there his personal life is marked by a search for the moral perfection, and in 1727 he is ordained as a Congregationalist minister in Massachusetts. His 1741 sermon, “Sinners In The Hands Of An Angry God,” describes the fate of those who wander from the Calvinist path:

O sinner! Consider the fearful danger you are in: it is a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath, that you are held over in the hand of that God, whose wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you, as against many of the damned in hell.

But beyond his oratorical power what shocks his fellow Congregationalists is his willingness to step down from the pulpit and engage with his flock in “revival meetings,” noted for highly emotional “spontaneous conversions” to the faith. These moments close the gap between the remote clergy on high and their congregation, and are adopted by many subsequent preachers.

In 1736 another new denomination arrives in America. The founder is an English minister named John Wesley, who, along with his colleague, George Whitefield, defines its tenets at Oxford College. Together they start a prayer group there called the “Holy Club,” so disciplined in its practice of piety that fellow students cast them as “The Oxford Methodists.” And the nickname sticks.

Wesley’s church combines the Arminian belief that all men are capable of achieving salvation with the Evangelical approach of revivalist meetings to attract new converts. But Methodism goes one step further in asking followers to engage in “reform missions” whereby they act to correct social injustices and support those in need. In the years to follow these missions address temperance and slavery.

With the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the Church of England followers come under suspicion of being loyal to King George rather than the American rebels. By its conclusion, most Anglican supporters are concentrated in the South, and the First Amendment to the new United States Constitution announces a fierce commitment to keeping the church separate from the state.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.

Church affairs are relegated to secondary status until after the domestic War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars in Europe are concluded and America’s national security is certain. At which time, from around 1825 to 1840, the population seems to step back collectively and consider how well they are living up the moral aspirations announced two hundred years earlier.

The period of reflection is known as the Second Great Awakening and it triggers a host of new religious thought and practices along with attempts at social reforms. Among them is the very controversial call to abolish slavery – an issues that will eventually cause a North-South schism in the major churches.

Of all the clergymen who propel the Second Awakening none has greater influence than the Reverend Charles Grandison Finney. He is born into a farming family in Warren, Connecticut, in 1792, the youngest of 15 children. After dabbling in the law, he happens to attend an 1821 religious revival meeting in the town of Adams, New York – and undergoes a spiritual transformation.

The Holy Spirit descended upon me in a manner that seemed to go through me… like the very breath of God. No words can express the wonderful love that was spread abroad in my heart.

Finney is ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1824, and sets off to spread the word of God, beginning in the Oneida county region of central New York. He stands opposed to the tenet of “predestination of the elect” espoused by Calvin, and in favor of the Arminian belief that salvation will come to all who embrace the “indwelling spirit” of Christ at hand. All that’s needed is to step forward at a revival meeting and make their commitment to be saved.

Once Finney lights the spark, revival meetings spread across America, with New York declared a “burnt out district” with no souls left to be saved. His success not only draws clerical acolytes, but also many leaders of the abolition and female rights movements, especially the philanthropists Arthur and Lewis Tappan. With their financial support Finney helps found Oberlin College, a hotbed of controversy for admitting black and female students during his tenure as President.

So-called “Old School” Presbyterians such as Reverends Lyman Beecher and Charles Hodge at Princeton University are appalled by the revival meetings and what they see as abandonment of the basic Calvinist tenet of predestination and the minister’s unseemly role in the conversions. They respond in the 1836 General Assembly session by expelling all “New School” synods from the official Presbyterian Church.

Meanwhile, the intellectual ferment of the Second Awakening also spawns a series of new and uniquely American religious movements.

At King’s Chapel in Boston William Ellery Channing announces the tenets of his Unitarian religion, whose roots trace to century’s old questioning centered in Poland and Hungary over the doctrine of the Trinity. According to Channing, Jesus Christ is not God Incarnate but rather one of many pious men whose lives and teachings reveal the path to salvation.

The Unitarians reject the notions of original sin and pre-destination of the elect in favor of the Arminian insistence on free will, and potential salvation of all who lead a life of virtue, like Christ. One faction, the Universalists, goes even further, positing that an infinitely merciful deity will forgive and save all, in the end. Followers are also expected to engage in “good works” and to treat all others with dignity and compassion. As such, many become leading proponents of abolishing slavery in America.

While controversy surrounds the Unitarians for denying the divinity of Christ, they reflect the Second Awakenings shift away from Calvinism and in favor of salvation for all through virtuous behavior, and church governance by the people not the clergy alone.

Often associated with Channing’s Unitarians are the Transcendentalists located mainly around the Harvard College campus and led by two intellectuals, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. They are known for their reliance on reason to formulate the search for meaning in life, and emphasize two core beliefs.

One being that the natural world is a powerful symbol of God’s hand in the universe. Thus the mundane works of man are “transcended” by the beauty, tranquility and lessons found in the great outdoors – and by experiencing them mankind is inspired to return to a proper life of simplicity and purity.

The other mark of the Transcendentalists is their conviction that the potential of each man and woman to reshape their lives and their societies is unlimited. As such, their intent is to restore the “rugged individualism” they feel built the nation and is in need of renewal.

Two additional uniquely American religious movements appear during the Awakening timeframe.

In 1823, Joseph Smith, an eighteen year old living in Palmyra, New York, experiences a vision of his personal salvation, and begins to share his story with others in his community. He tells of being visited by an angel named Moroni who reveals the location of a sacred book comprised of gold plates, compiled by the prophet, Mormon. He then describes his use of a “seer stone” to translate the engravings on the plates. The result is The Book of Mormon, which recounts a history of a long vanished Christian community living in America til 500AD.

Smith dedicates his life to recreating this community in a “New Jerusalem” under the banner of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints. After publication of his book draws a band of loyal followers, Smith begins the struggle to realize his vision. This will last from 1831 to 1847, require flights from local hostility in New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, and result in Smith’s murder, before his “Mormons,” under successor Brigham Young, reach their final destination in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Resistance to the Mormons traces to two main factors. First is the church adoption of “plural marriage” (or polygamy) defended as a way to promote rapid population growth but condemned by the general public as a sin against nature. Other anger is aimed at its very successful efforts to function as the nation unto itself (called “Deseret”), including a virtual monopoly over the territorial economy. The so-called “Mormon War” of 1857 is President Buchanan’s attempt to bring the Mormons to heel, but he is outsmarted at every turn by Young and the status quo ante resumes.

Church governance rests with a Quorum of Twelve Apostles a body of elders who serve for life and are succeeded from within the remaining congregation. The actual church rites identify Christ as the model of moral perfection, extend “exultation” to all who adopt Him as their savior, and require that good works include proselytizing missions to attract new members.

In 1832 another new religion appears. It is founded by William Miller, a New York farmer who begins as a Baptist before turning to Deism, with its reliance on personal study of the Bible and reasoning to define one’s faith. But Miller is then “born again” after surviving a perilous battle in the War of 1812. His scriptural study intensifies, and he concludes from Daniel 8:14 that the “second coming of Christ” will occur between March 1843 or 1844. A Baptist newspaper in Vermont publishes his forecast during the awakening fervor, and almost overnight thousands of believers become “Millerites.”

However when the March dates come and go, a stricken and contrite Miller issues a public apology, although still believing up to his death, that his miscalculation was probably minor. While most Millerites disband, one contingent concludes that the Daniel verse actually foretells an “ascension” of Jesus into the Most Holy Place in heaven rather than Miller’s promised return to earth. Further Bible study leads them to focus on observing the Sabbath from sundown Friday through sundown Saturday, and eventually they morph into the Church of the Seventh Day Adventists.

Although it’s clear that most early Americans are exposed to the Bible and its moral guidelines, data on actual church membership and attendance are lacking. Estimates vary widely, from a high of 75% to a low of only 20%. Despite this, there is agreement that the revival meetings of the Second Great Awakening sparked increases in church affiliation. Also that the denominations preaching the Arminian belief in the salvation of all virtuous people make gains relative to the dire predestination beliefs of the Calvinists. Hence the “Old School” Congregational Presbyterians lose ground to the Methodists, Baptists and “New School” Presbyterians in particular.

One other attempt at renewal arising from the Second Awakening is rooted in “socialism” rather than solely in religion. Its proponents are distressed by what they see as America’s many societal failures:

- The growing focus on material wealth eroding the drive for moral perfection.

- Competition to get ahead leaving some with too much and others with too little.

- Abject poverty among factory workers and other manual laborers.

- The denial of equal treatment for women and blacks and other minorities.

- Insufficient attention to improving the way children are educated.

- The lack of true spirituality within the traditional Christian churches.

- Overreliance on logic and reason drowning out man’s intuition and senses.

- Cities and factories isolating people from important connections to the natural world.

- Too much daily time and energy devoted to labor and too little to the intellect and the arts.

They respond by setting up “utopian communities” to seek perfection, following models of socialism gaining popularity at the time western Europe.

Examples of Socialist Utopian Communities In Early America

| Name | Where | When | Key Figures |

| New Harmony | Harmony Indiana | 1825-27 | Robert Owens |

| Nashoba | Germantown, Tenn | 1826-28 | Francis “Fannie” Wright |

| Brook Farm | West Roxbury, Mass | 1841-46 | George Ripley |

| Fruitlands | Harvard, Mass | 1842 | Bronson Alcott, Charles Lane |

Two of these communities in particular capture the spirit of these experiments and their outcomes.

The first is the New Harmony colony in Indiana, founded in 1825 by Robert Owen, an English atheist. He argues that poverty is the root cause of mankind’s afflictions and that the solution lies in socialism as espoused by two French contemporaries, comte de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier. His vision is of a society where personal self-interest is subjugated to the common good of all.

Owen recruits some 800 volunteers to establish his new “Moral World” based on equally shared labor and rewards for all, along with gender parity and an emphasis on early education and patterned lessons in caring and cooperation. But problems arise quickly, first around a shortage of food, clothing and basic household goods. In response, Owen divides the community into three groups – those responsible for agriculture, mechanics and manufacturing, schools and education. This fails, the result being finger pointing and animosity, with manual laborers criticizing “mind workers” as lazy idlers, and the conscientious upset by “free riders” who take more than they contribute. When departures pick up in 1827, a now personally bankrupt Owen closes New Harmony and returns to England.

Fourteen years later another utopian trial starts up under the leadership of Unitarian minister George Ripley and his wife Sarah. Ripley calls his new community the Brook Farm Association For Industry And Education. Its overtones are more religious than New Harmony, but it still relies on socialism to achieve its stated goal:

To redeem society, as well as the individual, from sin.

Ripley acquires a 200 acre farm and recruits 70 people promising “industry without drudgery,” a proper balance between labor and leisure, equal respect for physical and mental work and equal rewards for the thirty women and forty men in residence. Most residents are young and single, creating a college campus-like environment.

But as with New Harmony, the socialist model soon begins to fall apart when it comes to creating a viable economy. Ripley does start an excellent boarding school open to the public that generates profits, but these are insufficient to offset losses from the farming operation, and debts linked to new buildings. The cerebral Ripley gradually recognizes his financial plight:

The purely democratic, Christian principles (in) the community wouldn’t provide

even a single meal for seventy Brook Farmers living (here) in West Roxbury.

In response he adds more “manual labor-oriented” members, which renews his optimism and leads to two capital investments: one to construct his “Fourier-style Philanstery,” a giant rectangular building devoted to housing and work; and a steam engine to improve the milling operation.

But finances continue to erode, culminating in early 1846 when a party celebrating completion of the Philanstery ends in a fire that destroys the uninsured edifice. With only 30 residents left, Ripley closes Brook Farm in May 1846. To his credit, he pays off the accumulated debt of $17,445 by selling his library collection, and going on to work as a journalist.

Like New Harmony, the economic realities of socialism fail once again with Brook Farm. Still Ripley’s friend, Charles Dana, records some of its genuine accomplishments:

In the first place we abolished domestic servitude. In the second place we secured thorough education for all. And in the third place we established justice to the laborer, and ennobled industry.

While all of the above religious activity impacts white America, the black population is fighting to survive enslavement and searching for any form of spiritual support they can find.

Since arriving in chains, the religious experiences of the black population comprises an amalgam of the traditions brought from their homelands and the Christian precepts thrust at them in captivity.

For most Africans, indigenous religious beliefs revolve around “animism” – the conviction that supernatural forces, not individual volition, dictate the daily events and outcomes of men and nature. Instead of the single Christian deity, animism posits a host of lower and upper gods, each having their own realm of influence. Within this framework, man’s role is to “harmonize” with nature such that the gods are pleased.

This is accomplished in a variety of ways. One lies in veneration of the dead, signaling respect for the universal after-lives of those now in contact with the supernatural world. Magical rituals and sacrifices are also used to reach and appeal to the deities. “Voodoo,” imported to America from Haiti, invokes intermediaries such as “Papa Legba” to communicate with the gods. Among its rituals are gatherings where repetitive and intensifying incantations create trance-like states of possession among followers, aimed at achieving enlightenment and rewards. (These spontaneous conversions are not unlike those associated with the evangelical revival meetings.) Various forms of talisman or relics are also embraced by believers to seek favors, ward off evil, or even place hexes on enemies.

Instead of written scripture, the Africans rely on story-telling to hand down their theology of animism from one generation to the next. Instead of a formal clergy, certain village elders or wise men tend to be called upon to support spiritual intercessions.

However, the longer the Africans live in America the more they become exposed to the Christian creeds and liturgies of their captors. Indeed the tortured logic used by some owners to justify slavery claims that it allows the Africans to learn the path to Christian salvation!

Some come into contact with Christianity through mandatory Sabbath meetings on plantations where white masters deliver sermons to those enslaved. Others encounter it through contact with free black evangelists likely to be Methodists or Baptists.

But the real breakthrough for Christian theology among blacks belongs with two ministers: Reverends Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. Both are born into slavery in Delaware, then gain their freedom, and serve as lay clergymen at a Methodist Church in Philadelphia where they found the Free African Society to support emancipation.

After encountering racial animus for their successes, they start over and finally gain approval from existing hierarchies to form the first African Methodist Episcopal Church. It is a blend of the Arminian promise of salvation for all who strive for moral perfection, the Sunday liturgy and social service zeal of the Methodists, and the governance of the Episcopalians based on a bishop-led clergy.

In 1794 Allen and Jones open the “Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church” on Sixth Street in Philadelphia. Allen is the first pastor and the name “Bethel” is chosen to imply the union of many souls. Its motto stands as:

To arise out of the dust and shake ourselves, and throw off that servile fear, that the habit of oppression and bondage trained us up in.

Membership is limited to those “of the African race,” and it expands from a beginning congregation of 121 to 1300 by 1816. Criticism of its blacks-only policy that year leads to a new independent charter for the “AME Churches” including its branches in Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The Reverend Allen serves as the first official Bishop of the AME.

From then on the AME churches become safe havens for black people to worship and begin to adapt to their hostile social surroundings. They house run-aways and support the Underground Railway. In 1817 Allen’s Bethel Church also serves as the rallying point for those protesting “Colonization,” the proposal to relocate all freed slaves back to Africa. Freedom, citizenship, equality and assimilation now become the battle cries for many in the black community.

By 1846 the AME confederation includes some 176 clergy, 296 churches and over 17,000 members. While almost all sites are in the North, a scattered few appear mostly in the upper south such as Virginia and Kentucky. One startling exception is the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, begun in 1817 by the freed slave and black Unitarian pastor, Denmark Vesey. It however is destroyed by fire in 1822 after Vesey’s aborted attempt to lead a slave revolt. Secret trials end with Vesey’s execution along with 30 others suspected of involvement in the plot.

Baptists represent the other Christian church embraced by the Africans early on. It mirrors the Congregational ethos aside from restricting baptism to young adults. Before the 1775 Revolution, its band of roving preachers blanket the southern colonies with their messages of all men equal before God and freedom for those enslaved. Formal black Baptist churches are found in Savannah, Georgia in 1773 and in Petersburg, Virginia in 1774, although they are soon the source of concern among slave holders who fear they may encourage run-aways or uprisings.

The black church pleas for emancipation are met by silence from northern churches who fear that controversy will hurt attendance – and this persists until antagonism toward the southern “Slavocracy” intensifies. The issue that finally turns into a crisis is whether or not clergymen who are slave-holders should be forced to resign. In June of 1844 the Quadrennial meeting of the Methodist Episcopalians votes in favor of exclusion and the southern members break away. For the next 94 years the Wesleyan Methodist Church of the North will remain separate from the Methodist Episcopal Church of the South.

The same issue divides the Baptist Church in May 1845, with a crucial vote followed by a schism. The two factions become the Southern Baptist Convention vs. the Northern Baptists followers of their Triennial Convention.

South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun’s observation at the time will prove prescient:

Now nothing will be left to hold the states together except force.

As the outbreak of the Civil War approaches the Methodist Episcopalians have the largest membership with their combination of Arminian hopefulness for the salvation of all who strive to follow the Bible and their bishop-based form of church governance.

Estimated Number of Churches In America

| Denomination | 1790 | 1860 |

| Methodist Episcopalian | 700 | 20,000 |

| Baptist | 900 | 12,000 |

| Presbyterian/Congregational | 700 | 6,000 |

| Roman Catholic | NA | 2,500 |

| Jewish | NA | 77 |