Section #7 - John Brown’s Raid at Harper’s Ferry

John Brown’s Raid At Harpers Ferry: October 16-18, 1859

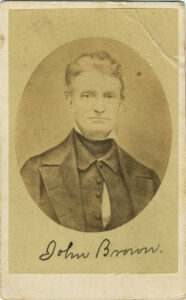

While the debate as to whether John Brown was a madman or a martyr will long endure, one thing about him is certain. He was unique among the abolitionist of his time for being not only eager to live among Blacks, but also willing to die for their freedom.

Becoming John Brown

John Brown is born on May 9, 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, the fourth of eight siblings. His mother dies when he is eight, and his youth is overseen by an overbearing father, Owen Brown, a strict Calvinist of the old school, who demands a life dedicated to achieving piety and self-perfection for himself and for his children.

From early on, John commits Bible verses to memory along with the hymns of the English Congregationalist minister, Isaac Watts: Am I A Soldier of the Cross, How Sweet and Awful Is the Place, I Sing the Mighty Power of God. At age sixteen, he publicly repents his sins and accepts Jesus Christ as his savior, then begins religious studies at the Morris Academy in Connecticut with a clerical career in mind. But funds for education run out, and at eighteen, he is back home apprenticing with his father in the tannery business.

Tanning is a particularly noxious occupation using human waste and chemicals to convert slaughtered animal hides into leather for shoes, belts, jackets and saddles. But Brown masters the process and, by age twenty, opens his own tannery which is successful enough for him to take a wife. Her name is Dianthe Rusk, and she is the daughter of his housekeeper. He describes her in utilitarian terms as “a neat industrious & economical girl, of excellent character, earnest piety & good practical common sense.”

He purchases a 200 acre parcel in 1826 at New Richmond, Pennsylvania, near the northwestern border of the state. He builds a cabin and a two story tannery there along with a barn that serves as an early station on the Underground Railway. He also founds a community with its own school, a church and other public buildings including a post office. In 1828 he is even named postmaster by President JQ Adams.

Brown has an ambitious plan for himself, to raise and sell his own cattle, while slaughtering some for hides to make and sell finished leather goods. His dreams, however, fade by 1832, when his wife dies after an “instrumented-aided” delivery of her seventh child over a ten year period. Brown himself then suffers a prolonged illness that curtails his work and leads to the first of many episodes of stifling debt.

In 1833, he marries his second wife, the sixteen year old Mary Day, who will eventually bear 13 more children. Brown is the patriarch of the family in the mold of his father Owen. Daily life begins with a morning gathering where Brown requires each member of the family to read Bible verses, followed by delivering his own religious admonitions. Trespasses are met with whippings as recorded for his first son, John Jr.:

For disobeying mother………………..8 lashes

For selfishness at work………………..3 lashes

For telling a lie…………………………….8 lashes

In 1836 more financial mismanagement finds him moving back to Ohio at Franklin Hills where he tries his hand at surveying, farming, selling horses and investing in state bonds. But what capital he builds is wiped out by the emerging bank panic.

Throughout this turmoil, Brown, as a dedicated Calvinist, continues to search after God’s plan for his life.

He finds the answer in 1837 when he learns of the murder of abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy by angry citizens in Alton, Illinois. He gathers his family together and reveals his intent to go to war against slavery.

His oldest son, John Jr., age thirteen at the time, recalls this event years later: He asked who of us were willing to make common cause with him in doing all in our power to “break the jaws of the wicked and pluck the spoil out of his teeth. Are you Mary (his second wife), John, Jason and Owen?” As each family member assented, Brown knelt in prayer and administered an oath pledging them to slavery’s defeat.

He declares his own public commitment at a prayer meeting at the First Congregational Church of Hudson, Ohio to honor Lovejoy’s memory. Toward the end of the service, Brown stands, raises his right hand, and makes a pledge:

Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my

life to the destruction of slavery!

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: 1800-1837

| May 9, 1800 | Born in Torrington, Connecticut |

| 1808 | Mother dies and strict father, Owen, raises him |

| 1816 | Briefly attends Morris Academy with eye to joining clergy |

| 1818 | Opens his own tannery in Hudson, Ohio |

| 1820 | Marries first wife, Dianthe Rusk, who will bear his first 7 children |

| 1826 | Moves to New Richmond, Pa. and founds a community there |

| 1832 | Dianthe dies and he is in financial straits |

| 1833 | Marries second wife, Mary Day, who delivers 13 more children |

| 1836 | Move to Franklin Hills, Ohio struggling as farmer, surveyor, selling horses |

| 1837 | Publicly dedicates his life to ending slavery after abolitionist Lovejoy’s murder |

Opposition to slavery is nothing new to Brown, whose father, Owen, is a strident abolitionist. In his autobiography, he writes that his antipathy begins when he is 12 years old, and witnesses a young black boy being “beaten with iron shovels.” As early as 1834, Brown tells his brother Frederick that he is “trying to do something in a practical way for my fellow men that are in bondage.” His efforts include petitions protesting Ohio’s “black codes,” hiring freed men to work on his farm, and having a freed black sit in his church pew which leads to his expulsion.

But again financial difficulties get in the way of his mission. In 1842 he declares bankruptcy, and tries to dig out by leveraging his skill with animal husbandry, this time raising prize winning sheep. In 1846, he leaves Ohio and moves to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he pins his monetary hopes on selling wool.

Springfield is already a hotbed of abolition fever and after Brown joins the Sanford Street Free Church he hears a lecture by Frederick Douglass and meets with him to share his vision for ending slavery.

Brown is convinced that the South will never free its slaves without a violent confrontation occurring on its own soil. He tells Douglas in 1847 that he intends to spark this outcome by recruiting, arming, training, and leading a small band of fellow whites, freemen and black slaves in a series of guerrilla raids on Virginia plantations. After each attack, he will retreat into the sanctuary afforded by the Allegheny and Appalachian Mountains, where he expects to welcome an ever growing army of run-aways to the cause.

Brown sees precedents for his plan in Nat Turner’s five week long rebellion in 1831, and in the successful black uprising led by Toussaint L’Overture in Haiti at the turn of the century. Douglass listens but encourages Brown to seek a peaceful solution.

In 1846-7 North-South tensions over slavery are exacerbated by the Mexican War, which results in the cession of 529,000 square miles of new territory in the west. The South views the land as a windfall for its economy, a chance to open new plantations and increase sales of their two major “crops:” raw cotton to foreign markets and “excess bred slaves” to new start-up planters.

But then comes a political shock, delivered by Pennsylvania Congressman, David Wilmot, who offers a “proviso” to an appropriations bill to fund the army. It agrees to the expense…

Provided that, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any

territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty

…negotiated between them… neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever

exist in any part of said territory.

When this Wilmot Proviso passes in the Northern dominated U.S. House, the South uses its power in the Senate to temporarily table the amendment. But the message here is plain: many, perhaps a majority, of Northerners are intent on banning slavery (and even free blacks) in the west, and reserving the land for “Free (White) Men and Free Labor.”

As the war plays out, John Brown’s a wool trading partnership in Springfield with Isaac Perkins, is collapsing. In 1849 he leaves Springfield and moves his wife and seven children to North Elba, New York, to join an “experimental community” founded by the philanthropist and abolitionist, Gerrit Smith. It is another of Smith’s many reform schemes, in this case intended to teach slaves and freedmen to become successful farmers. Brown purchases a 244 acre plot and joins the community.

This North Elba land will become home base for Brown over the decades to follow. He focuses first on putting his financial house in order, dividing his time between farming the land alongside his black neighbors, and trying to restore his other business interests in Springfield, some 220 miles to the south.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: 1838-49

| 1842 | Turns to raising prize sheep after declaring bankruptcy |

| 1846 | Moves to Springfield, MA to run wool selling businessJoins Sanford Street Free Church and hears Frederick Douglass lecture |

| 1847 | Tells Douglass of his plan to assault Virginia plantations and free slaves |

| 1849 | Wool trading business collapses and moves to North Elba, New YorkJoins Gerrit Smith’s “experimental community” to teach blacks about farming |

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act Is A Call To Action

His Virginia mission, however, is revived in 1850 by passage of a new Fugitive Slave Act, a congressional order aimed at placating the South. The Act requires northerners to participate with bounty-hunters in the capture and return of run-away slaves or face heavy fines.

Brown is outraged by the prospect and organizes what he calls his “League of Gileadites,” a mixed band of 45 black freedmen and whites dedicated to protecting run-aways around New York, Springfield and Boston. In his mind, the League stands as a precursor to the strike force he hopes to recruit in Virginia.

Brown’s Gileadites are joined by other local “vigilance committees” who resort to violence to resist police attempts to return run-aways. This outcome, plus the ongoing threat of the Wilmot Proviso to ban slavery in the west, prompts the South to search for other ways to defend itself.

The answer comes in the form of the Kansas-Nebraska Act which the Illinois Democrat, Stephen Douglas, bullies through Congress in 1854. Instead of a Wilmot-like federal bill on slavery in the new territories, it proposes an option called “popular sovereignty” – or “let the people decide” on Free or Slave State status.

But slipped into the bill is a rider which calls for terminating the 1820 Missouri Compromise, including the agreed upon 36’30” boundary line – which would automatically make both Kansas and Nebraska Free States. When accusations of reneging on a “settled” compromise arise, Douglas simply shrugs them off arguing that “popsov” is more democratic than any fixed line.

His opponents will have none of that, and the 1854 Bill sparks the creation of the Republican Party and the return of Abraham Lincoln to the political stage.

It also sets off a six year “rehearsal for the Civil War” in the Kansas Territory over whether the state will be designated as Slave or Free. In theory the decision will be made by local residents in fair and free elections. But from the beginning it’s clear that Southerners, particularly in next door Missouri, are determined to win the first test of “popsov” by any means possible.

On November 29, 1854, an election to select a representative to Congress brings a flood of Slave State supporters from Missouri across the river, led by U.S. Senator David Atchison, to

stuff the ballot boxes for their candidate. Four months later this is repeated in a vote to choose members of what becomes known as the “Bogus State Legislature.”

As word of the frauds filter east, five of Brown’s sons and their families emigrate from Ohio to Kansas in the spring of 1855: the eldest, John, Jr., at 34 followed by Jason, Fred, Owen and the youngest, Salmon, at 19. They become part of the Free State vanguard, and settle in a camp called “Brown’s Station” eight miles west of the town of Osawatomie.

Permission for the move comes from their father, who wants to join them but decides to stay back east for the moment. In June 1855, he attends a gathering of Radical Political Abolitionists including Gerrit Smith, Lewis Tappan and Fred Douglas, and raises initial funds to buy weapons for his cause. He then ponders whether to proceed with his grand scheme to attack Virginia, but decides that Kansas must come first.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: 1850-55

| 1850 | Founds his “League of Gileadites” to resist new Fugitive Slave Act |

| Mar 29, 1855 | Pro-Slavery forces from Missouri steal election for Kansas Legislature |

| 1855 | Five of his sons emigrate from Ohio to Kansas to make it a Free StateHe joins Radical Political Abolitionists and becomes a fundraiser for Kansas |

Brown Becomes Notorious In “Bloody Kansas”

On August 13, 1855, fifty-five year old John Brown loads up a wagon with arms and heads west along with his son-in-law, leaving his wife behind, and the North Elba farm in the hands of his 21 year old Watson. He arrives at Brown’s Station on October 7.

In the interim, a Free State Party convention has been held comprising a dissonant mix of those intent on keeping all blacks out of Kansas and a smaller group of abolitionists. The first Territorial Governor has also been sacked by President Franklin Pierce for trying to overturn the fraudulent elections. By December 1855 the Free Staters have written and approved their Topeka Constitution which would ban slavery – but, to Brown’s chagrin, would also prohibit black residency!

Violence soon escalates between the two sides. Pro-slavery Sheriff Samuel Jones is wounded in the Free State capital of Lawrence and on May 21, 1856 a retaliatory strike led by ex-Senator David Atchison’s 700 man pro-slavery militia destroys the town. Four cannon turn the buildings to rubble before the raiders leave unscathed.

Three days later, Brown and four of his sons embark on revenge in what will be known as the Potawatomie Massacre. By 2am on May 25, five thought-to-be pro-slavery men have been hacked to death with broadswords and left in the woods near their farms. Despite the awful brutality of the murders, Brown dismisses them:

It is better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should pass away

by a violent death than that slavery should live on.

The sack of Lawrence and Brown’s massacre usher in a series of violent confrontations between the Free State and Pro-Slavery sides, along with attempts by both to get their constitutions approved in Washington. President Pierce and his successor, James Buchanan do everything possible to shut down the Free State initiatives, including the use of U.S. Troops to disband the Topeka legislature. They do so knowing that their own political future, and that of the Democrat Party, depends on sweeping Electoral College votes across the Southern states.

Within a year John Brown” is both famous – and notorious – nationwide for his Pottawatomie Massacre, his defense of the Free State forces throughout Kansas, and his victory at the Battle of Black Jack. Along with “General” James Lane, “Osawatomie John Brown” is now the symbol of all who oppose the expansion of slavery in the territories.

The price he pays for his crusade will be punishing. On August 30, 1856, Brown loses his son Fred during the futile effort to defend his hometown. He becomes the first of three sons who will eventually die alongside their father.

By the Fall of 1856, Brown is a hunted man in Kansas, both among the pro-slavery forces and the local U.S. Marshal who is intent on jailing him and trying him for murders committed. He flees for his life in early October, smuggled in a wagon to Tabor, Iowa, an Underground Railroad stop, where he recuperates before heading back east.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: 1855-56

| Aug 13, 1855 | Leaves North Elba for Kansas, arriving there on October 7Joins sons at Brown’s Station near Osawatomie |

| May 21 | Free State capital at Lawrence destroyed by Pro-Slavery marauders |

| May 25 | Brown plus 4 sons hack 5 Free-Staters to death in Potawatomie Massacre |

| June 4 | Leads victory in Battle of Little Jack |

| Aug 30 | Suffers defeat at Osawatomie where son Fred killed |

| October | Escapes Kansas for now headquarters at Tabor, Iowa |

Brown Refocuses On His Harpers Ferry Assault

Brown will eventually return to Kansas, but now shifts his attention toward his Virginia plan. He has chosen to assault Harpers Ferry because of its prominence to the U.S government as a federal arsenal, its armory of weapons and its many nearby plantations. He expects it to fulfill his prophecy:

I have only a short time to live – only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause.

There will be no more peace in this land until slavery is done for. I will give them something

else to do than to extend slave territory. I will carry the war into Africa (i.e. the South).

To do so will require assembling, arming and training his army of black and white warriors, and this becomes his next challenge. But first he must acquire needed funds, and in January, 1857, he goes back east to find them.

He has previously known the wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith during his time in North Elba, but now extends that circle to include other prominent figures: journalist Franklin Sanborn, Dr. Samuel Howe, the Unitarian ministers, Thomas Higginson and Theodore Parker, and the industrialist, George Stearns. All are convinced that violence will be needed to end slavery, and their support of Brown’s Virginia plan earns their label “The Secret Six.”

Brown address the National Kansas Committee in January and the Massachusetts Legislature on February 18, 1857. From there he crisscrosses New England asking for donations. In Boston he meets with other abolitionists including Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips and Charles Sumner, still recuperating from a severe beating at the hands of a Southern Congressman on the floor of the Senate.

In March he encounters the Transcendentalists, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. While neither share his beliefs about Blacks, they see in him the personal virtues they applaud: a man living close to Nature, with the individual Courage to take Action against government policies they oppose. Brown doesn’t know it at the time, but Emerson in particular will help transform his image across the North after the Harpers Ferry raid.

Also in March, Brown advances his military plan. A blacksmith shows him a 6-foot long pike he sees as ideal for his slave revolt, and he tops it with a double-edge Bowie Knife. He orders 500 of these and, while never used in battle, they become symbolic of his savage intent. He then selects an-ex British soldier of fortune named Hugh Forbes to train his troops for the Virginia campaign, a move that will soon backfire on him.

After a visit to New Elba to see his wife, he starts the long journey back to Tabor, Iowa, finally arriving there along with 200 revolvers on August 7, 1857. He has contracted malaria along the way and is laid up with it through October. When he recovers, he heads to Kansas to find recruits for his Virginia army and sends Forbes back to Ashtabula, Ohio to set up a training camp. Brown turns up about ten recruits before starting out for Ohio in December 1858 to check in with Forbes.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: 1857

| January 1857 | Heads east to find supporters and funds for his Virginia assault |

| February | Makes pleas to National Kansas Committee and Massachusetts Legislature |

| March | Meets Transcendentalist Emerson and Thoreau who applaud himSelects 6 foot long pike with Bowie Knife to arm his slave armyHires ex-British soldier of fortune Hugh Forbes to train his troops |

| August 7 | Arrives back at Tabor, Iowa with 200 revolvers But also sick with malaria that lays him out for three months |

| August 9 | Trainer Hugh Forbes arrives at Tabor and confers on plan |

| November 5 | Sends Forbes off to Ashtabula, Ohio to set up training camp |

| December 4 | Brown and first ten recruits begin trip to Ashtabula |

Brown’s Virginia Plan Is Stalled

Forbes accuses Brown of reneging on their deal and complains in person to Samuel Howe, several U.S. Senators and finally to newspaperman, Horace Greeley.

He is a man who would not keep his word…a reckless man,

an unreliable man, a vicious man.

Not all believe his story about a planned Virginia attack, but the rumors send Brown into hiding for three weeks in Rochester at Fred Douglass’ home. While there, he updates Douglass on progress and drafts what he titles a Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States. It calls for the Union to be preserved, but the Constitution replaced by one ending slavery and making Blacks citizens with the right to vote. The visit also moves Douglass toward the New York abolitionists who call for violence not mere “verbal suasion.”

In April 1858, he swings north to Chatham, Canada, where he befriends Harriet Tubman and presides over his own “Abolitionist Convention” on May 8-9. His audience of 34 blacks and 12 whites hears his latest plans including a black army revolt in Virginia. He is pleased with the meeting until he learns the next day that not only has Forbes left Ashtabula, but has also started a vendetta to ruin him.

More bad news comes his way at a May 20, 1858 meeting with the Secret Six. All but Thomas Higginson are unnerved by the Forbes publicity and demand that Brown suspend any military action in the south.

Brown doesn’t know it at the time, but this “pause” will last for 17 months.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: Early 1858

| January | Orders recruits to winter at Springdale, Iowa while he continues to OhioWhen he arrives, he finds that Hugh Forbes has departed |

| February | Hides out in Rochester, NY, at Frederick Douglass’ homeDrafts his Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the US Updates Douglass on his Virginia invasion plan |

| March | Travels to Boston disguised as “Nelson Hawkins” to meet Secret Six |

| April | In Chatham, Canada where he meets Harriet Tubman |

| May 8-9 | Holds his own “Abolitionists Convention” in Chatham |

| May 10 | Hears disastrous news of Hugh Forbes betrayal and vendettaThe Secret Six tell him to pause operations in VirginiaThe aftermath stalls his plan for 17 months |

Brown Returns To Kansas In 1858

In order to preserve the funds he has raised, he must now convince donors that they were to be used all along in Kansas, not Virginia. To do so, he arrives on June 25, 1857, in Lawrence, Kansas, disguised as “Shubel Morgan.” His goal is to advance the Free State cause there while also spotting recruits for his own army.

The political situation in Kansas when Brown arrives still favors the Pro-Slavery side, with recently inaugurated President James Buchanan dedicated to getting their Lecompton Constitution through Congress, and a new Governor, Robert Walker, assigned to shut down the Free State Party legislature. The appearance of U.S. Troops at hot spots in the state has diminished the level of violence.

Brown’s stated intent upon returning is to avoid bloodshed and maintain a low profile to avoid further spooking his eastern funders. He will so for almost the next 18, spending most of this time lecturing and fundraising on behalf of the Free State Party.

Two noteworthy events occur during this interregnum. First, the Marais des Cygnes Massacre on May 19, 1858, where a Pro-Slavery band executes eleven Free Staters in cold blood. Second, a fairly held “popsov” election on August 2 that rejects the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution by a 10:1 margin and will go on to insure that Kansas enters the Union (in 1860) as a Free State.

The Marais des Cygnes murders in particular re-ignite Brown’s desire to make another bold statement against slavery, and he seizes the chance on December 20, 1858. Along with a band of twenty, he rides across the river into Missouri, raids three plantations, rounds up eleven slaves, and carries them back to Kansas for safety.

Over the next 82 days, he personally leads them all the way to Detroit before putting them on a ferry to Canada and freedom on March 12, 1859.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: Early 1858

| January | Orders recruits to winter at Springdale, Iowa while he continues to OhioWhen he arrives, he finds that Hugh Forbes has departed |

| February | Hides out in Rochester, NY, at Frederick Douglass’ homeDrafts his Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the US Updates Douglass on his Virginia invasion plan |

| March | Travels to Boston disguised as “Nelson Hawkins” to meet Secret Six |

| April | In Chatham, Canada where he meets Harriet Tubman |

| May 8-9 | Holds his own “Abolitionists Convention” in Chatham |

| May 10 | Hears disastrous news of Hugh Forbes betrayal and vendettaThe Secret Six tell him to pause operations in VirginiaThe aftermath stalls his plan for 22 month |

| May 19 | Pro-Slavers execute 11 Free Staters in the Marais des Cygnes Massacre |

| August 2 | In a free and fair elections, Pro-Slavery Lecompton Constitutions loses 10:1 |

| December 20 | Brown leads 20 man band into Missouri to free 11 slaves |

The Time Has Come For The Virginia Raid

The successful incursion in Missouri convinces his eastern backers, especially Gerrit Smith, that the time has arrived for his Virginia attack.

Brown heads east from Detroit, addresses a large anti-slavery rally at Oberlin College and visits with Ohio’s abolitionist Governor, Joshua Giddings. He then arrives at Smith’s mansion on April 11, receiving praise and more donations from the Secret Six and the Transcendentalists.

June 11 marks his final visit to his home in North Elba. It lasts only five days, much of it devoted to discussions about the upcoming attack and Brown’s wish to have his sons accompany him to Virginia.

Three agree to go: Oliver at twenty and Watson at twenty-one will both suffer gut-shots in the battle and die slow and agonizing deaths, while Owen at thirty-four will fight and escape to safety, living for thirty more years. Thirty-eight year old John Jr. will oversee the shipment of some 198 Sharps rifles and 200 revolvers, but will be absent when the battle takes place.

Tough-minded Salmon at twenty-two, is convinced that the attack will fail, says that to his father, and refuses to sign on. Jason, a gentle soul at twenty-six, also bows out.

With their fates decided, the Browns head to the Kennedy Farm in Maryland to meet up with the rest of the volunteers and begin training for their assault. The farm is on two acres of land roughly five miles north of Harpers Ferry. Brown has rented the property from heirs of the deceased Dr. Robert Kennedy under the alias of “Isaac Smith.” He pay $35 on a lease running until March 1860, signaling his intent to be a long-term settler.

On July 3, 1859, Brown, his son, Oliver and a black recruit named Osborn Anderson move to the farm, along with Oliver’s pregnant wife, Martha, and Brown’s daughter, Anne. Both women are sixteen years old, and their duty will be to handle the housekeeping chores and act as look-outs on the property, until just before the raid.

Some 105 days now remain until the bloodshed begins.

While Brown is elated that the day of reckoning is near, there are still many details left to prepare for the attack. To celebrate the Fourth of July he drafts his own version of the Declaration of Independence which will later be found at the farm. It reaffirms his intentions

for the new Provisional Government.

To secure equal rights, privileges and justice for all…We will obtain these rights

or die in the struggle to obtain them. We make war upon oppression.

By the end of August, twenty of the men who will fight at Harpers Ferry are present on the farm. They will be crammed into tight quarters, as the cabin consists of only two rooms, and much of the barn space is given over to the eventual storage of weapons. But most are accustomed to living rough in the outdoors, and they settle in nicely.

Their daily routine consists of reading Hugh Forbes manual on guerrilla tactics, training with their weapons, debating religion and politics, singing songs and keeping up with the news via the Baltimore Sun, brought to them by one of their own, John Cook, who has been living in town for over a year to scope out the operation.

On Sundays, John Brown attends the local Dunker Church. During the week, he is called upon by neighbors to act as veterinarian for their sick farm animals. Efforts to conceal their purpose are wanting all along, with the men sending details to their families back home and engaging in loose talk. Secretary of War John Floyd even receives an anonymous letter in August citing Brown’s presence and intentions in Virginia, but discards it as implausible.

A moment of real tension occurs when, for the first time, many of the men learn that the initial attack will be made on the U.S. Arsenal. Like other Brown supporters – including members of the Secret Six – the assumption is that the plantations in and around Harpers Ferry are the target, not federal property. Upon hearing to the contrary, “Captain” Charles Tidd and several other predict failure, but Brown eventually brings them around.

In mid-August Fred Douglass visits the Kennedy Farm and Brown tries to recruit him:

Come with me Douglass. I want you for a special purpose. When I strike, the bees (i.e. slaves) will begin to swarm, and I shall want you to help hive them.

After listening to Brown’s plan, Douglas declines the invitation, and tells his old friend, “I believe you will die there.”

While disappointed, the meeting does result in Brown’s final recruit, twenty-three year old, Shields Green, a fugitive slave from Charleston, S.C., who has accompanied Douglass to the farm. He will go to Harpers Ferry, fight, be captured and subsequently hanged.

In early September the weapons supplied by the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee and the Secret Six arrive at the Kennedy farm. Included are 198 Sharps rifles and 200 Maynard revolvers, although the latter still need priming devices to make them functional. They are followed at the end of the month by the supply of “John Brown’s Pikes,” which he intends to distribute to the men he frees. As he says with great assurance:

Give a slave a pike and you make him a man.

With the Fall harvesting season approaching, Brown believes that the overworked slaves will be most prone to join his army. But how he intends to spread the word remains unclear.

On September 29, 1859 he takes another step forward, ordering the two women to leave the farm and return home for safety. He gives a note to his daughter Anne, telling her to “save this letter to remember your father by.” Oliver Brown’s pregnant wife Martha also says good-by to her husband for the last time. Both will be dead within the next six weeks, he from a mortal wound in battle, she following an illness after losing her newborn baby.

Thoughts of impending death also mark the correspondence of the other would-be soldiers. While Charles Tidd escapes in the end, his fears about the assault on the armory persist, and he writes his parents:

This is perhaps the last letter you will ever receive from your son.

Two men who will die during the battle assume the worst while trying to rationalize it in their own minds. Jerry Anderson writes…

If my life is sacrificed, it can’t be lost in a better cause.

John Kagi says that if he dies, “the result will be worth the sacrifice.”

As September ends, the men are just sixteen days away from discovering their individual fates.

Milestones In John Brown’s Life: Early 1858

| April 11 | Visits Secret Six and gets go-ahead for Virginia plan |

| June 11 | Final visit to North Elba; 3 sons agree to accompany him, 2 do not |

| July 3 | He arrives at the Kennedy Farm headquarters |

| August | Twenty recruits at the farm; Douglass turns down offer to join |

| September 29 | Weapons have arrived and Brown orders women to return home |

The Final Countdown Begins

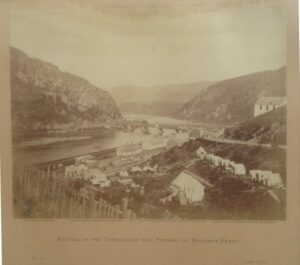

The town of Harpers Ferry predates the American Revolution.

In 1761 the Virginia General Assembly gives Robert Harper the rights to run a ferry across the Potomac River from the Maryland Heights to the east, into the town which will ultimately bear his name. Thirty years later the federal government acquires land at the point to construct a second U.S. Arsenal to supplement its first at Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1824 a wooden bridge is constructed to span the river, and in 1839, a single track railroad line is added by the B&O, making Harpers Ferry one of its central hubs. By 1859 the town is flourishing, with a population of some 2,500 citizens.

John Brown means to violate its serenity and security beginning Sunday evening, October 16.

In early October he has made one final departure from the Kennedy Farm, meeting with John Jr. and John Kagi in Philadelphia to put the finishing touches on his raid. While there, he picks up his final recruit, a fifth black man, Francis Merriam, who will successfully escape after the fight. Merriam will arrive at the last minute, bringing with him rifle primers and caps, along with a $600 donation from Lewis Hayden, a run-away slave who has prospered as a merchant.

With Merriam on board, Brown has a total of twenty-two men in his Provisional Army, well short of the fifty he had hoped for, but enough, he believes, to achieve victory.

On October 15, 1859, he gathers the men together to announce that the Revolution would get under way the next day, Sunday, October 16.

It is the Sabbath, and the day begins with Brown reading from the scriptures and asking for God’s support for their righteous endeavor.

He turns symbolically to Osborne Perry Anderson, born a free black, to walk through the final assignments.

Three men – Owen Brown, Francis Merriam and Barclay Coppoc, will stay at the Kennedy Farm to begin.

The other nineteen will march in strung-out pairs to assemble near the Potomac River Bridge. Once there, each pair will have an assigned task:

Brown’s Detailed Plan To Assault Harpers Ferry

| Assigned Tasks | Who |

| Cut the telegraph wires to the outside world | John Cook & Charles Tidd |

| Capture the guard at the railroad bridge over the Potomac | John Kagi & Aaron Stevens |

| Guard the railroad bridge as the action plays out | Watson Brown & Stewart Taylor |

| Capture the 2nd bridge to town over the Shenandoah River | Oliver Brown & Will Thompson |

| Seize the Engine House where trains are stored | Jerry Anderson, Dauphin Thompson, Wm Leeman |

| Seize the U.S. Arsenal where 2,000 rifles are stored | Albert Hazlett & Edwin Coppoc |

| Seize Hall’s Rifle Works, largest gun mfr. In the South | John Copeland & John Kagi |

| Move to the countryside and begin freeing slaves | Aaron Stevens, Charles Tidd, John Cook,Shields Green, Perry Anderson, Lewis Leary |

| Stay back and guard the Kennedy Farm | Owen Brown, Francis Merriam, Barclay Coppoc |

The Attack Begins

The operation starts like clockwork. By midnight Sunday, Brown is in control of both bridges into town, plus the key structures he is after, the Armory, U.S. Arsenal, the Fire Engine House, Hall’s Rifle Works. His six outriders have captured Colonel Lewis Washington, the great grand-nephew of the former president, along with another planter and six slaves, and have brought them to the Armory building fronting the Potomac. All this without any casualties.

Then comes a moment when Brown’s hopes fall apart.

After the slaves he has freed are assembled he passes out his pikes and asks them to guard their four white prisoners. Their response, however, is fear not empowerment. As one slave

who refuses to handle the pike, reportedly tells Brown:

I don’t know nuffin’ bout handlin’ dem tings.

The others exhibit comparable alarm and puzzlement. Who is this white man in charge? Have they been taken to be sold down south? What form of savage retaliation will they face if their masters recapture them?

Brown is shocked by this response and on the spur of the moment, alters his entire plan. Instead of escaping into the hills to assault more plantations, he will now make his stand against slavery at Harpers Ferry.

Soon thereafter his party begins to lose the advantages of surprise. At 1:30am an eastbound train is halted at the railroad bridge and an alarmed baggage porter named Shephard Hayward is mortally wounded by shots from Oliver Brown and Stewart Taylor. He is a free black man, and the first to die at the site.

As Monday, October 17, dawns, John Brown allows the train across the bridge, despite having earlier cut down the telegraph lines to conceal his presence. It arrives at Monocacy, Maryland and wires news to Baltimore that “150 abolitionists have taken Harpers Ferry, killed the porter Hayward and are freeing slaves.” This report is ignored until 10:30am when the B&O line president wires the news to President Buchanan and Governor Henry Wise of Virginia. Wise orders two militia units, the Jefferson Guards and the Botts Greys, to move east from Charles Town to the Ferry, seven miles away.

In the interim, the townspeople and local militias swarm toward the Armory where Brown is now holding some 30 hostages he has rounded up on the farms and in town. From beginning to end, he promises not to harm them, and he keeps his word.

But further violence is now inevitable, and the next death belongs to an Irish grocer in town named Thomas Boerly, shot by Dangerfield Newby, the freed slaves who comes with Brown in hopes of freeing his wife and family held on a nearby plantation. But this rescue is not to be, as Newby is gunned down while running along the bridge to the shelter of the Armory. Newby will be the first of the eight raiders who will lose their lives in action of October 17. After his death, the angry crowd cuts off his ears and genitals, jabs sticks into his wounds, and feeds his remains to feral hogs. Variations on this level of savagery will also accompany the treatment of several other members of Brown’s band who are captured or killed.

By mid-afternoon on Monday, the window of opportunity for Brown to flee from Harpers Ferry closes for good.

Last Stand At The Firehouse

In town at the Hall’s Rifle Works factory, Brown’s second-in-command, John Kagi finds himself trapped along with Lewis Leary and John Copeland. All three run for their lives out the back and down to the Shenandoah River, attempting to swim to safety. Kagi is quickly shot dead, while Copeland is dragged to the shore and jailed along with Leary, who is mortally wounded and will die on October 20.

As the afternoon wears on, more local militias and armed citizens surround Brown’s survivors inside the Armory. His options now are to surrender, fight or negotiate his way out. He tries the latter, sending Will Thompson out under a white flag of truce. It is ignored and Thompson is taken into custody.

With desperation setting in, “Old Osawatomie” decides to consolidate most of his remaining forces at the best structure in sight, the town’s Fire Engine House, later famous as “John Brown’s Fort.” It is a one story brick structure comprising some 36 x 24 feet in space. Brown selects eleven of his highest profile hostages and moves them there, along with seven of his troopers: his sons, Owen and Watson; his son-in-law, Dauphin Thompson, his long-time Kansas sidekicks, Aaron Stevens and Jerry Anderson; the mild-mannered Quaker, Edwin Coppoc; and his final recruit, Fred Douglass’ friend and fugitive slave, Shields Green.

Jerry Anderson and Albert Hazlett will remain hiding in the Armory, which is unguarded when they find it and largely overlooked throughout the action.

Despite his first failed attempt at negotiating, Brown tries again, this time sending Aaron Stevens and his son, Watson, out under a truce flag. Both are immediately shot. Watson is struck in the bowels and crawls back inside the Fire Engine House, groaning in agony. Stevens is badly wounded and transported to the Armory as a prisoner. Seeing this, Will Leeman panics, and dashes out of the building and down to the Potomac River. He dives in and is wounded before trying to surrender. With his hands up, he is shot in the face. His body remains on a rock in the river, where it is used as target practice for the irate attackers.

About this same time, John Cook, reaches the east side of the Ferry bridge and climbs a tree to reconnoiter the status of conditions in the town. His day has been spent as an out-rider, rounding up the liberated slaves, and waiting back at the Kennedy Farm, along with Charles Tidd and three others, each with limited physical capacities: Owen Brown with a crippled arm from childhood, Barclay Coppoc, suffering from consumption, and the frail and easily rattled, Francis Merriam.

Cook sees the overwhelming militia and civilian forces gathered around the main buildings, then hears by word of mouth that Brown and seven other raiders have all been killed. With that, he turns back to the Kennedy Farm and tells the others that it would be “sheer madness” to try to cross the bridge. Together the five men pack their gear and escape into the mountains.

Four of the five will succeed, but not John Cook. After hiking 100 miles, the five men are near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, when Cook ventures out for supplies on October 26, He is recognized, captured for the $1,000 bounty on his head, and returned to Richmond where he is hanged on December 16, 1859.

Around 3pm, the locals are further enraged when the popular Mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, is killed by a bullet fired by Edwin Coppoc from inside the Engine House. This loss, along with that of another prominent citizen, George Turner, prompts the mob to haul Will Thompson, captured earlier under a flag of truce, out of his cell at the Waters Hotel and march him to the railroad station. Once there he is tied to a post and shot to death, and his corpse is throw into the Potomac.

The next casualty is Brown’s youngest son, Oliver. He is firing out from the Engine House, when a shot catches him in his intestines. He is laid out next to his brother, Watson, suffering from the same excruciating wound. Oliver will die during the night of October 17-18; Watson will linger, succumbing on the 19th, after telling his captors: “I did my duty as I saw fit.” Stewart Taylor is also shot and dies after three hours inside the Engine House.

As darkness falls, the two raiders hidden in the overlooked Arsenal, manage to sneak down to the Potomac and cross over in a skiff. After trying, unsuccessfully, to connect with the other escapees from the Kennedy Farm, they head to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where Hazlett, like John Cook, is spotted, captured, returned to Virginia and hanged. Perry Anderson is luckier, eventually making it all the way to Canada. Of the five blacks in Brown’s party, Perry Anderson is the only one to survive.

Meanwhile, in town, Captain Thomas Simms of the Frederick Militia enters the Engine House under a white flag and talks about possible surrender terms. But Brown insists on free passage for his men back across the river, in exchange for his eleven hostages, and Simms demurs.

It is 11PM on October 17 when 52 year old Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee arrives on the scene accompanied by ninety U.S. Marines. Lee is a career military officer, having served in the Mexican War and as Superintendent of West Point from 1852-55. Given Brown’s isolation and the mob scene he encounters, Lee decides to delay a move against the Engine House until the morning of the 18th.

Dawn on Tuesday, October 18, finds 1st Lieutenant Jeb Stuart under a white flag peering into the Engine House and, for the first time, recognizing that the assumed “Mr. Smith” who rented the Kennedy Farm is none other than the Kansas renegade “Osawatomie Brown.” Their meeting is brief, Stuart demanding unconditional surrender, Brown still countering with safe passage in exchange for his captives.

When Stuart exits, he crouches behind the heavy door and raises his hat, signaling a twelve man unit under the command of 2nd Lt. Israel Green to rush the building, with battering rams and fixed bayonets at the ready.

Brown waits inside with his eleven hostages, including Lewis Washington, his dead son Owen and his dying son, Watson, the corpse of Stewart Taylor, along with four able bodied defenders: Edwin Coppoc, Jerry Anderson, Dauphin Thompson and Shields Green.

The assault is brief but bloody. The one marine casualty is Private Luke Quinn, born in Ireland and joining the corps in 1855. His death merely adds to the lust for revenge in the congested room.

Jerry Anderson and Dauphin Thompson are killed by bayonet thrusts, while Edwin Coppoc and Shields Green are taken alive.

It is Lt. Green who attacks John Brown, stabbing and slashing him repeatedly, but with an officer’s sword rather than a more lethal cavalry saber. Thus instead of dying on the scene, Brown survives. He is bleeding badly when carried to the Armory and laid next to Aaron Stevens, captured earlier at the Rifle Works. His interrogation will begin there.

Overview Of Attack At Harpers Ferry

| October 16 | |

| Midnight | Perfect start to attack; control over town; have hostages and set of slaves |

| October 17 | |

| 1:00am | Slaves reject pikes and Brown revises plan; will make final stand in town |

| 1:30 | Eastbound train stopped and black porter is killed |

| 7:05 | Train arrives at Monocacy, Va. and announces the attack at first ignored |

| 10:30 | Governor Wise learns of attack and orders Va. Militia to the scene |

| Mid-day | Town grocer killed along with first raiderThree raiders at Rifle Factory try to flee; 1 killed and 2 captured |

| Afternoon | Townsmen surround Brown in the Armory and truce attempts failShifts his men and hostages to the Firehouse as more killed |

| Evening | Two raiders escape scene for the ArmoryReinforcements from Kennedy Farm turn back after observing the situationRobert E. Lee and Virginia Militia arrive at 11:00pm |

| October 18 | |

| Dawn | Lee assaults the Firehouse, captures Brown and frees hostagesHe is wounded and Oliver and Watson Brown are dead |

Sidebar: Fates Of The Twenty-Two Men At Harpers Ferry

Of the twenty-two men who participate in the raid, ten are killed in action:

- Five die outright: Newby, Kagi, Leeman, Jerry Anderson, Dauphin Thompson

- One is summarily executed: Will Thompson

- Four succumb to mortal wounds: Oliver and Watson Brown, Taylor and Leary

Five are captured at the scene:

- Three are unhurt in the fighting: Quaker Edwin Coppoc, John Copeland and Shields Green

- Two others, Brown and Aaron Stevens, surrender after being severely wounded

Two flee, but are caught near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania by bounty hunters:

- John Cook, who has lived in, and scouted, Harpers Ferry for a year before the raid

- Albert Hazlett who is able to slip out of the Arsenal

All seven of those taken into custody are tried, convicted and hanged.

Brown goes first and is convicted on October 31 and dies on December 2.

Four more follow shortly, with Edwin Coppoc found guilty on November 3; the two black men, Copeland and Green, on November 4; then Cook, despised for betraying his neighbors in town who call for him to be lynched. All will be hanged on December 16, Copeland and Green in the morning, Coppoc and Cook in the afternoon.

Trials for the other two, Aaron Stevens and Albert Hazlett, are delayed when the term of the current court expires. They will be convicted in February 1860 and executed on March 16.

That leaves the five men who successfully escape. Three share similar fates, enlisting in the Union army and dying soon thereafter. Barclay Coppoc dies in a troop train accident in 1861 at age 22; Charles Tidd of disease in 1862 at 28; and Francis Merriam, also at 28, of disease in 1865.

Two live on. One is Osborn Perry Anderson, the only black who survives, and writes his own account of the incident before dying at 42 in 1872. The other is John Brown’s third son, Owen, who has been at his side since the Pottawatomie massacre and will reach age 65 before his death in 1889.

| Killed Outright | Age | Race | Profile | Dates |

| Dangerfield Newby | 24 | B | Slave in Va, freed, at HF to free his family | KIA 10/17 |

| John Kagi | 24 | W | Ohio, Kansas militia, 2nd in command to JB | KIA 10/17 |

| William Leeman | 20 | W | Maine, settles in Kansas | KIA 10/17 |

| Will Thompson | 25 | W | NH, son-in-law to JB, brother of Dauphin | Executed 10/17 |

| Jerry Anderson | 26 | W | Indiana, Kansas, Missouri raid with JB | KIA 10/18 |

| Dauphin Thompson | 21 | W | NH, North Elba neighbor, in-law Watson B | KIA 10/18 |

| Mortally Wounded | ||||

| Stewart Taylor | 22 | W | Canada, wagon maker | 10/17, dies 10/17 |

| Lewis Leary | 24 | B | NC, born a free black, Oberlin | 10/17, dies 10/20 |

| Oliver Brown | 20 | W | 10/17, dies 10/18 | |

| Watson Brown | 24 | W | 10/17, dies 10/19 | |

| Hanged Later | ||||

| John Brown | 59 | W | Hangs 12/2/59 | |

| John Cook | 29 | W | Conn, law, Kansas, lives in HF for year | Esc, hangs 12/16 |

| John Copeland | 25 | B | NC, Oberlin, nephew of Lewis Leary | Jail, hangs 12/16 |

| Edwin Coppoc | 24 | W | Ohio, Quaker, Kansas but not fighting | Jail, hangs 12/16 |

| Shields Green | 23 | B | SC, run-away, friend of Fred Douglas | Jail, hangs 12/16 |

| Albert Hazlett | 22 | W | Pa, with Montgomery in Kansas | Esc, hangs 3/16/60 |

| Aaron Stevens | 28 | W | Conn, Mexican War, Kansas militia | Wd, hangs 3/16/60 |

| Successful Escape | ||||

| Perry Anderson | 29 | B | Born a free black in Pa, attends Oberlin | Esc from Armory |

| Owen Brown | 24 | W | JB’s stalwart 3rd son, longest survivor at 66 | Esc from Farm |

| Barclay Coppoc | 20 | W | Ohio, Quaker, meets JB Springdale, Ia | Esc from Farm |

| Francis Merriam | 21 | W | Mass, in Kansas but not fighting | Esc from Farm |

| Charles Tidd | 25 | W | Maine, Missouri raid with JB, fears failure | Esc from Farm |

The Trial

John Brown’s behavior and words over the 45 days between his capture on October 18, 1859 and the time he is hanged on December 2 have much to do with changes in the way he is perceived by the public at large in the North.

Newspaper reporters pour into Harpers Ferry from along the east coast by the time he is taken. So too do various politicians, eager to pepper him with questions about the raid. A three hour grilling is completed while he is still prone in the Armory. Virginia congressman Alexander Botelier asks if Brown if he “expected to get assistance here from whites as well as blacks?”

I did, and yes, I have been disappointed.

Two other Virginians, Senator James Mason and Governor Henry Wise, are joined by the pro-Southern Ohio Governor Clement Vallandingham in a series of questions:

Q: Who funded you?

A: I cannot implicate others.

Q. Mr. Brown, who sent you here?

A. It was my own prompting and that of my Maker.

Q. What about the loss of innocent lives?

A. If there was any killing of innocent people, it was without my knowledge.

Q. Did you consider this a religious service?

A. It was the greatest service man can render to God.

Q. Do you consider yourself an instrument in the hands of God?

A. I do.

Brown ends this initial interrogation with the first of many words that will appear in newspaper and other written accounts over time:

I wish to say, furthermore, that you had better – all you people of the South –prepare

yourselves for a settlement of this question. You may dispose of me very easily…but

not the negro question. The end of that is not yet.

Those expecting to hear the rantings of a lunatic abolitionist are thrown by Brown’s demeanor and responses. When asked to characterize his prisoner, Governor Wise replies:

They are themselves mistaken who take him to be a mad man. He is a man of clear

head, of courage, fortitude and simple ingenuousness. He was humane to his prisoners

…(also) vain and garrulous, but firm, truthful and intelligent.

Vallandingham is also surprised by Brown:

Captain John Brown is as brave and resolute a man as ever headed an insurrection….He

is the farthest possible remove from an ordinary ruffian, fanatic or mad man. Certainly

his was one of the best planned and best executed conspiracies that ever failed.

While both men will soon regret these initial remarks, they do reflect a certain grudging admiration for Brown’s code of conduct, which seems in many ways to mirror the Southern ideal. He commits himself to fighting for his cause. His plan of attack is bold and meticulous and well executed. He exhibits great personal courage during the battle, surrendering only after being severely wounded. He protects his hostages from harm. His responses when captured are forthright and his manner is that of a gentleman. He shuns excuses and awaits his fate with dignity.

He may be Osawatomie Brown of Kansas fame, but Governor Wise and other who now encounter him find that his bearing and words resonate with many of the cavalier traditions of the South.

Brown’s demeanor, however, does nothing to delay the cry for swift retribution. Together with the four others in custody, he is transferred to Charles Town, the seat of government for Jefferson County, located seven miles to the west of Harpers Ferry.

The intent of his captors is try Brown first, and then move on later to his associates. With that in mind, the wounded warrior is formally indicted on October 25, 1859, one week after the raid. The charges include treason against Virginia, inciting slaves to violence, and murder. In the interim, arrangement are made for a trial and lawyers are chosen to defend him. He responds with dismissiveness:

If I am to have nothing but a mockery of a trial…I do not care anything about counsel. It is unnecessary to trouble any gentlemen with that duty.

His wishes are ignored and the trial begins the following day in a courtroom packed with some 500 spectators, many smoking cigars, consuming roasted peanuts and contributing shouted curses as they deem appropriate.

Judge Richard Parker, a former US congressman, presides, and Brown is initially defended by two southern lawyers who encourage him to plead “hereditary insanity” to escape a death sentence. Brown brushes away this idea before two northern lawyers arrive for his defense. Judge Parker rejects their plea for a delay, and they plunge forward arguing that his mission was humanitarian in nature, the slaves did not riot, all hostages were treated with respect and were unharmed, and that the deaths were not premeditated but the result of combat.

Furthermore, since their client was not a citizen of Virginia, he could not be guilty of treason against the state.

Closing statements from both sides occur on October 31 and the jury is dismissed to deliberate. They do so for forty-five minutes before returning a verdict of guilty on all counts.

Sentencing occurs on November 2, before which Judge Parker offers Brown the chance to address the court, and he does so with words and demeanor that, once publicized, cause observers on both sides to re-think their beliefs about his sanity and his actions..

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say…

I deny everything but what I have admitted all along…a design on my part to free the slaves…I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I believe that to have interfered as I have done…in behalf of His despised poor, I have done no wrong, but right.

Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say, let it be done.

Like Governor Wise, some Southerners who are present are moved by the dignity and eloquence of this address.

But words alone are hardly enough to dismiss the profound sense of community and sectional terror created by the raid – and Parker sentences Brown to death by hanging, one month hence.

Hearing the news, abolitionist Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator newspaper tells its readers to…

Let the day of his execution…be the occasion of such a public moral demonstration against the bloody and merciless slave system as the land has never witnessed.

Brown continues to enhance the impression he makes on his captors, and on the outside world during the twenty-nine days which follows his sentencing. A reporter who interviews him remarks on his Calvinist convictions:

Captain Brown appears perfectly fearless in all respects. Says that he has no feeling about death on a scaffold and believes that every act, even all follies that lead to disaster, were decreed to happen ages before the world was made.

His own correspondence reinforces his belief that freeing the slaves was his God-given destiny, and that goodness will come from his actions.

I feel quite cheerful in the assurance that God reigns & will overrule all for His glory & the best possible good.

He also reflects on the past, especially to his time in Kansas, and his role in the Pottawatomie Massacre. On this count, he seems to give himself the benefit of the doubt:

I never shed blood of my fellow man except in self-defense or in promotion of a righteous cause.

As the end draws near, he recognizes that his final contribution to his cause will come on the scaffold. He writes as much to his half-brother, Jeremiah:

I am worth inconceivable more to hang that for any other purpose. …I have fought

the good fight and have finished my course.

His concerns are for the future well-being of his family. He admonishes them to study the Bible and to abhor slavery. He pleads with his wife to stay home to avoid the emotional turmoil of his execution and to conserve their money. He asks that a handful of slaves accompany him to the gallows and that his body be burned along with his two dead sons, Watson and Oliver.

Mary Ann Brown, his wife of 26 years and mother of 13 of his 20 children, ignores his pleas and arrives on the day before he is executed. She spends four hours with him, but is convinced to not witness his death. His request that she be allowed to stay with him through the night is denied.

The Execution

On his way out of jail toward the gallows on December 2, Brown hands another prophetic note to one of his guards:

I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be

purged away, but with Blood. I had…vainly flattered myself that without very much

bloodshed it might be done.

Crowds gather to get a final glimpse of the prisoner, but few succeed, since a hyper cautious Governor Wise floods the town and the surrounding roads with troops to prevent any possibility of a last second rescue. Some 3,000 armed guards are present, comprising local militias and 264 federal troops, again under Robert E. Lee.

The execution site is also cordoned off from the public, except for a few who manage to slip through. Among them are John Wilkes Booth posing as a militia member, and the prominent fire-eater, Edmund Ruffin, who already intends to build his case for Southern secession around the Harpers Ferry incident.

The scaffold is freshly built for the occasion. The platform is 12’ by 16’ and six feet high, reached by twelve stairs. At the front is a crossbeam with a short noose hovering over a trap door. Brown arrives along with his coffin and an undertaker named Sadler who tells him:

You’re the gamest man I ever saw, Captain Brown.

Brown replies:

I was so trained up; it was one of the lessons of my mother; but it is

hard to part from friends.

He has refused the offer of a clergyman, so climbs the stairs and moves to the trapdoor on his own. Observers comment on his dignified manner and unwavering courage. His hat is removed, and a white linen hood is fitted over his face. His only request is that the sentence be carried out without ceremony and quickly. But he is forced to stand still for almost ten minutes as mounted troops are brought into place.

When the trap-door is sprung, his drop is only two feet, but fortunately it is enough to snap the spinal cord in his neck, and he dies quickly. After another thirty-five minutes his body is cut down and placed in his coffin.

Colonel Preston issues the final official word at the scene:

So perish all such enemies of Virginia and of the Union and of the human race.

Wilkes Booth records a different coda in his diary:

He was a brave Old Man.

Trial, Execution And Burial: 1859

| October 25 | Brown indicted for murder and treason |

| October 31 | Found guilty after 45 minute jury deliberation |

| November 2 | Sentenced to be hanged |

| November 8 | Emerson speech praising Brown: |

| December 2 | Issues final prophecy and is hanged |

| December 3 | Wife Mary starts journey to North Elba with his body |

| December 7 | Burial back home |

Interment Back Home

On December 3, Mary Ann Brown begins a five day journey with her husband’s corpse, by train to Philadelphia and boat to New York, followed by a 25 mile trek overland to the farm in North Elba.

She wishes to take her two dead sons along, but Brown’s request has been denied. Watson’s body is handed over to the Winchester Medical School for anatomical research, while Oliver’s remains, along seven others are thrown into two crude pine boxes and buried alongside the Shenandoah River. (By 1899 the remains of the two sons, along with nine other raiders will be acquired and reburied next to Brown.)

A small and simple memorial service follows on December 7. His body is transferred to a new casket by his family, and it is left open while his neighbors and other friends file past.

He is then lowered into a nearby grave next to a huge bolder where he has carved his name in case he should die at Harpers Ferry. His headstone – moved years before from Connecticut to the farm — is that of his grandfather, Captain John Brown, who lost his life fighting in the American Revolution. Brown’s name, along with those of Oliver and Watson, are added below the original inscription.

The ceremony itself is simple and brief. It is marked by the singing of his favorite inspirational hymn:

Blow ye the trumpet, blow.

The gladly solemn sound;

Let all the nations know,

To earth’s remotest bound,

The year of Jubilee has come.

Final tributes are spoken by several attendees, including Wendell Phillips:

Marvelous old man! He has abolished slavery in Virginia…History will date Virginia Emancipation from Harpers Ferry. His words, they are even stronger than his rifles. They crushed a State. They have changed the thoughts of millions, and will yet crush slavery.

John Brown’s story would seem to end here – but it is hardly over.

Prominent Figures Villify Brown Nationwide

Shock waves reverberate across the South even after John Brown is in his grave. He symbolizes that worst nightmare for a civilized society, a homegrown terrorist – and they respond to the fear he has triggered in predictable fashion. First they try to search out and punish the perpetrators, and then to tighten their local security to prevent future attacks.

As usual, the easiest target for punishment are the blacks in their presence — and any whose prior behavior suggests a threat are subject to beatings, lynchings and even burning at the stake. The extent of the retributions here is unknown, but it likely matches or exceeds those following the Nat Turner uprising.

But this time the spotlight even extends to the 353,000 free blacks living across the South alongside its 3.9 million slaves. The state of Maryland asks whether it is time to put an end to “free negroism.” North Carolina follows up by passing legislation whereby all free blacks are given a choice between becoming “re-enslaved” or leaving the state. Mississippi and Arkansas eventually do the same.

Attention also falls on suspected “white collaborators.”

These include anyone thought to be harboring anti-slavery sentiments. As rumors spread, “Black Lists” materialize from town to town, along with local boycotts of any businesses run by “negro sympathizers.”

Attempts are also made to interdict publications and other materials from the North that are deemed to be critical of slavery. Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune becomes a leading example, along with the Springfield Republican and Harpers Weekly Magazine.

The intent of these moves is well articulated by an editorial in the Atlanta Confederacy:

We regard every man in our midst an enemy to the institutions of the South who does not boldly declare that he believes African slavery to be a social, moral, and political blessing. If not he should be requested to leave the country!

Along with the above, efforts are made to strengthen the response time and effectiveness of local militias to deal with any future crises.

Meanwhile in the North, the press and politicians join the South in condemning Brown. The New York Evening Post says that Brown was “driven to madness” by his actions in Kansas, and Harpers Ferry was the tragic result. The Chicago Press and Tribune writes that no one could “approve the (raider’s) means or justify their ends.” Even the abolitionist editor, Horace Greeley, initially calls it “the work of a mad man.”

As for the politicians, two are immediately criticized for being involved in some fashion. New York Senator Henry Seward legitimately denies any role in the plot. Ohio Governor Joshua Giddings, who has had frequent contact with Brown, responds deceptively, that “Brown never consulted me.”

Other prominent anti-slavery lawmakers join in. John Hale “deeply regrets” the raid; Salmon Chase sees it as “an insane attempt;” Ben Wade says “it is absurd to implicate the Republican Party in the acts of John Brown.” Lincoln says that the raid is “wrong for two reasons…a violation of law and…futile as far as any effect it might have on the extinction of a great evil.”

Even Brown’s closest backers, members of the Secret Six, distance themselves after a large cache of their incriminating correspondence with him is uncovered at the Kennedy Farm.

Gerrit Smith suffers a nervous breakdown and enters an insane asylum, while Parker remains in Italy and Stearns, Sanborn, and Howe flee to Canada, soon followed by Frederick Douglas.

At first it seems that the Unitarian Minister, Thomas Higginson, Brown’s staunchest loyalist among the Secret Six, will be left standing alone in Boston to defend his attack on slavery.

But soon enough that changes, as the general public across the North embrace Brown for finally dealing a blow to the arrogant Southern “Slavocracy.”

The General Public In The North Rally Behind Brown

The first sign of support for Brown comes from the New England Transcendentalists. Their campaign to rehabilitate him is led by Ralph Waldo Emerson, America’s leading intellectual, whose mastery of the spoken and written word have defined the public’s notion of heroism for over two decades.

On November 8, 1859, twenty-four days before Brown is hanged in Virginia, Emerson delivers a lecture at the Music Hall in Boston on three “qualities which conspicuously attract the wonder and reverence of mankind:” selflessness, practicality and courage. The third quality, “courage,” takes him to a prior conversation he has had with Brown.

Captain John Brown, the hero of Kansas, said to me that ”for a settler in a new country, one good, believing, strong-minded man is worth a hundred, nay, a thousand men without character, and that the right men will give a permanent direction to the fortunes of a state.”

John Brown is no madman, according to Emerson; instead a successor to “the best of those who stood at our bridge on Lexington Common” – ready to sacrifice himself in service to a higher law. From there comes a line that will register alongside his prior “shot heard round the world.” It refers to Brown as…

That new saint than whom none purer or more brave was ever led by love of men into conflict and death,—the new saint awaiting his martyrdom, and who, if he shall suffer, will make the gallows glorious like the cross.

While few Northerners accept Emerson’s image of Brown as Christ, their animosity toward the South has been growing for years. From the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act to the warfare in Bloody Kansas and the Democrat’s bullying to make it a Slave State, most have had enough.

The vast majority among the Northern public reject John Brown’s beliefs about the equality of Blacks or his wish to free them and make them citizens. But they do applaud the kind of bloody nose he has delivered to the South at Harpers Ferry. So he soon emerges as another of the archetypal icons embedded in the American psyche:

The right-minded vigilante, exercising frontier justice on his own,

to strike out against the wrong-doers in the name of essential justice.

Nowhere is reverence for John Brown greater than in the free black communities of the North. Special praise for him comes from Charles Henry Langston, born in Virginia to a white planter, educated at Oberlin College, and a founder of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. Langston asks his audience “why should I honor the memory or mourn the death of any of the white people of this land?” He answers his own question, in praise of John Brown:

A lover of mankind – not of any particular class or color, but of all men…He fully, really and actively believed in the equality and brotherhood of man…He alone has lived up to the Declaration of Independence…He admired Nat Turner as well as George Washington.

The South Demands A Congressional Investigation

Nowhere is the Harpers Ferry raid more impactful than on the remaining Southern moderates who have long resisted calls to secede from the Union.

The reality of a white madman fomenting a Nat Turner-like slave uprising on their farms and then being applauded convinces most that the North is their mortal enemy, out to destroy their way of life.

A special investigating committee is set up in the Senate on December 14, 1859, to gather facts on the raid and propose legislation to prevent its repetition. It is chaired by known secession advocate James Mason of Virginia and runs from January 4 to June 15, 1860. Testimony is taken from 32 witnesses albeit missing key figures like Hugh Forbes, four of the Secret Six, John Brown Jr., and Frederick Douglass.

But those expecting prosecution of individuals linked to the raid are disappointed. One report written by Mason simply calls for stronger measures to guard federal arsenals. A second, by Vermont’s Republican Senator Collamer, points the finger at congressional defenders of slavery for triggering the violent response.

Mere words are not enough to alter minds already made up regarding the raid.

The Aftermath

Five months after the Harpers Ferry report is issued, Republican Abraham Lincoln becomes America’s 16th President with a majority of Electoral Votes, but only 39% of the popular vote, all cast in the North. His promise to ban slavery in the west prompts seven southern states to exit the union before he is even inaugurated. On April 13, 1861 the Confederates bombard Ft. Sumter and John Brown’s final prophecy is fulfilled – “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

And bloody it is. Before the Civil War ends, the body count of dead Americans will reach some 750,000 or 2.3% of the entire population.

North And South Reactions To Brown And Harpers Ferry

| Nov 8, 1859 | Before execution, Emerson praises Brown: the new saint awaiting his martyrdom, and who, if he shall suffer, will make the gallows glorious like the cross. |

| December | Politicians in North condemn Brown and the attack of Secret 6 flee along with Fred Douglass. Majority of Northern public applaud him for giving South a bloody nose. Free Blacks hail Brown as their hero. Congressional inquiry is anti-climactic; all minds already made up |

Ironically the conflict further immortalizes John Brown, after Union soldiers frame a marching tune in 1861 called The Battle Hymn of the Republic:

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

But his soul goes marching on.

Chorus:

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

His soul goes marching on.