Section #9 - Growth Of Our Cities and Economy

Growth of Our Cities and Economy

You are there:

America’s town and cities create the concentrated marketplaces needed for a booming national economy.

When the British colonists arrive, their first challenge lies in locating a viable place to settle – and they are naturally drawn for water, supplies and transportation to sites along rivers, lakes or bays.

By 1630, many of the nation’s original towns and cities have taken root, including Boston and New York.

Some Of The Very Earliest Cities In America

| Year | Name | State | Claimant | Body of Water |

| 1565 | St. Augustine | Fla | Spain | Matanzas River |

| 1607 | Jamestown | Va | Britain | James River |

| 1607 | Santa Fe | NM | Spain | Santa Fe River |

| 1610 | Hampton | Va | Britain | Chesapeake Bay |

| 1613 | Newport News | Va | Britain | James River |

| 1614 | Albany | NY | Britain | Hudson River |

| 1617 | Jersey City | NJ | Britain | Hudson River |

| 1620 | Plymouth | MA | Britain | Eel River |

| 1622 | Weymouth | MA | Britain | Back River |

| 1623 | Dover | NH | Britain | Pisquataqua River |

| 1623 | Gloucester | MA | Britain | Annisquam River |

| 1625 | New York | NY | Britain | Hudson River |

| 1626 | Salem | MA | Britain | Forest River |

| 1630 | Boston | MA | Britain | Back Bay |

They are joined by others as the 17th century plays out, notably Charlestown and Philadelphia.

Again they are adjacent to waterways and two are even to the west: Green Bay and El Paso

Other Early American Cities

| Year | Name | State | Claimant | Body of Water |

| 1630 | Biddefield | Me | Britain | Saco River |

| 1632 | Williamsburg | Va | Britain | James River |

| 1634 | Green Bay | WI | Britain | Fox River |

| 1635 | Concord | MA | Britain | Concord River |

| 1636 | Providence | RI | Britain | Providence River |

| 1636 | Springfield | MA | Britain | Sangamon River |

| 1636 | New Haven | CT | Britain | West River |

| 1637 | Hartford | CT | Britain | Connecticut River |

| 1638 | Cambridge | MA | Britain | Charles River |

| 1638 | Wilmington | Del | Britain | Christina River |

| 1639 | Newport | RI | Britain | Narragansett Bay |

| 1639 | Guilford | CT | Britain | Coginchaug River |

| 1639 | Bridgeport | CT | Britain | Pequonnock River |

| 1639 | St. Marks | Fla | Spain | St. Marks River |

| 1642 | Warwick | RI | Britain | Pawtuxet River |

| 1642 | Lexington | MA | Britain | Charles River |

| 1646 | New London | CT | Britain | Thames River |

| 1649 | Annapolis | Md | Britain | Severn River |

| 1649 | Marblehead | MA | Britain | Massachusetts Bay |

| 1651 | Norwalk | CT | Britain | Norwalk River |

| 1659 | El Paso | TX | Spain | Rio Grande River |

| 1660 | Rye | NY | Britain | Hudson River |

| 1666 | Newark | NJ | Britain | Passaic River |

| 1668 | Sault Ste. Marie | MI | Britain | St. Marys River |

| 1670 | Charleston | SC | Britain | Cooper River |

| 1673 | Worchester | MA | Britain | Blackstone River |

| 1674 | Waterbury | CT | Britain | Naugatuck River |

| 1680 | So. Orange | NJ | Britain | Rahway River |

| 1681 | Philadelphia | Pa | Britain | Schuylkill River |

| 1682 | Norfolk | Va | Britain | Chesapeake bay |

Building these settlements is an onerous task. It begins from scratch by cutting trees, clearing ground and putting up stockade fencing to protect against any and all external threats. Some early enclaves fail to survive, such as the Roanoke Colony in North Carolina and the Popham Colony in Maine. They are unable to find enough food, clothing and shelter to live through the harsh winters. Or they fall victim to disease, especially outbreaks of smallpox and scurvy.

But once the survivors gain a territorial foothold, they are anxious to realize their dreams of owning and farming their own land. Support comes in the Congressional Land Ordinance in 1785 which peg the price at an affordable $1 per acre.

Thus the first Census in 1790 finds 93% of the population residing on farms and only 7% in urban centers. Even future mega-cities like New York and Philadelphia boast only 30,000 or so residents, with most of them engaged in shipping traffic between American and European ports of call.

Urban Centers in 1790 Census

| Name | Population |

| New York | 33,131 |

| Philadelphia | 28,522 |

| Boston | 18,320 |

| Charleston | 16,345 |

| Baltimore | 13,503 |

| No. Philadelphia | 9,913 |

| Salem | 7,921 |

| Newport | 6,716 |

| Providence | 6,380 |

| Marblehead | 5,661 |

| Average | 14,641 |

However, from 1800 forward the urban centers grow rapidly, as America’s market economy takes off.

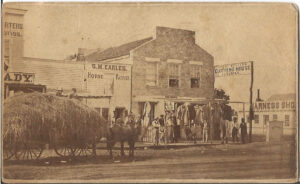

The transition begins with “demand,” the wish among farmers for more material goods to improve their daily lives. Included here are household goods like shoes, clothes, furniture, cookware and tableware; occupational necessities such as shovels and plows, horseshoes and saddles; rifles and traps; even “luxuries” like books, musical instruments, clocks, paper and pencils.

Rather than the often impossible task of trying to make these things on their own, the chance of buying or bartering for them in a central marketplace becomes attractive.

But on top of demand, three other things are required for this market to materialize.

First there must be manufacturers to produce the supply of the goods in demand.

For much of America’s first two centuries these “finished goods” are manufactured in Europe and shipped across the Atlantic. This pattern changes, however, when leaders like Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay push for increases in domestic production.

A breakthrough occurs in 1813 when Francis Lowell opens his Boston Manufacturing Company and follows it with two new textile mills converting fiber into yarn and yarn into cloth. Lowell memorizes the production systems he has seen in a prior visit to Britain and duplicates them in his own plants. He preaches “specialization,” setting up factories with one end product in mind. Then carefully “mapping” the steps required and optimizing the processes used at each stage to insure high throughput and uniform quality.

To keep the prices of his textiles competitive, Congress imposes “protective tariffs” on foreign imports. Some of these tariffs cover clothing made in Britain with raw cotton from southern plantations – which in turn depresses their profits and adds to regional tensions already brewing over slavery.

While Lowell leads the way on manufacturing textiles, other capitalists are busy launching some of America’s earliest and most famous “branded” products.

Earliest Manufacturer Brands In The U.S.

| Year | Brand Name | Industry |

| 1795 | Dixon Ticonderoga | Pencils |

| 1796 | Jim Beam | Distillery |

| 1798 | Pratt Read | Tools |

| 1801 | Crane & Co. | Papermaking |

| 1802 | DuPont | Chemicals |

| 1806 | Colgate | Consumer Goods |

| 1807 | Sterling Sugars | Sugar |

| 1811 | Pfalzgraff | Ceramics |

| 1812 | Waterbury Button | Buttons |

| 1813 | Conti Group | Meat Products |

| 1815 | Loane Brothers | Tents |

| 1816 | Remington | Firearms |

| 1818 | Brooks Brothers | Clothing |

Once there is an adequate “supply” of goods to meet “demand,” the next hurdle lies in having the infrastructure in place to transport them across the nation.

By 1800 America’s road systems have developed to the point where they are capable of handling most commercial traffic. Some are short postal routes connecting two nearby towns; others cover long-distances like the King’s Highway (1650) the Fall Line Road (1735), the Great Wagon Road (1744). Even the west coast will soon be reachable via the Oregon Trail (1811), the Santa Fe Trail (1822) and the California Trail (1847).

From 1825 onward these once dirt trails are also being “macadamized,” covered over with crushed stone and properly beveled to minimize closures due to rain and winter conditions.

The final part of the “marketplace creation model” lies in a concentrated location where the manufacturer’s goods meet up with the farmer’s demand to complete the “money for products” exchange.

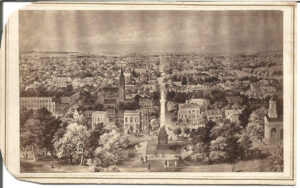

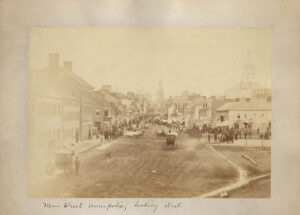

The marketplace takes shape in America’s urban centers — and they are perfectly designed for this purpose.

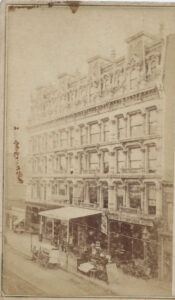

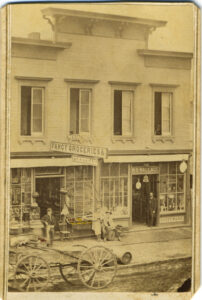

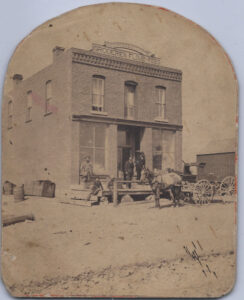

Unlike most European cities, America’s urban centers eschew concrete walls and moats in favor of open-ended “main streets” that invite people in rather than keeping them out. Their purpose is to promote commerce rather than visits to approved religious or government edifices. The reason to come to town is to visit the general store or tavern, not to worship or pay taxes.

Finally, they are typically laid out in a grid pattern with easily followed streets rather than the confusing axial patterns and circuses familiar to the old world.

The author of America’s city grid system is William Penn, who is deeded 4500 square miles of land by King Charles II in 1681 to pay off a prior debt. The 37 year old Quaker decides to found a city at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers which he names Philadelphia, from the Greek for love (phileo) and brother (adelphos). He envisions his city devoted to commerce and divides it into surveyor “plats,” striving for functionality and aesthetics.

Penn’s American grid streets are straight; avenues are 100 feet wide while lesser streets are a generous 50 feet across; four large public squares are set aside for green space; detached homes are encouraged and uniform frontage includes space for gardens; an area is designated for a public school; and streets are named for trees to reinforce the association with nature.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 recognizes Penn’s achievements and establishes a blueprint for surveying public domain property into townships comprising 36 designated “plats.”

By around 1815 all four components of a viable industrial economy have come together in America: demand + supply + transportation + urban center marketplaces.

And the results are already apparent in the nation’s “gross domestic product” results, which grows from $189 million in 1790 to $925 million in 1815.

Gross Domestic Product For The United States*

| Year | 1790 | 1795 | 1800 | 1805 | 1810 | 1815 |

| GDP (MM) | $189 | $383 | $480 | $561 | $706 | $925 |

| % Change | +103% | +25% | +17% | +26% | +31% |

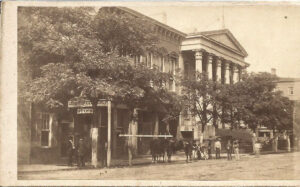

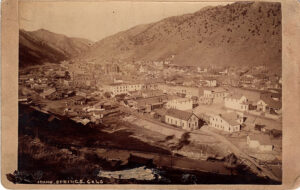

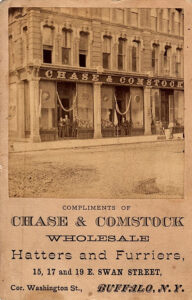

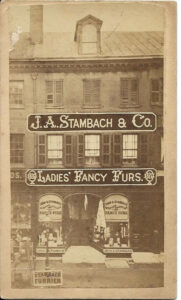

Consistent with the growth of the economy are population gains in the cities as more residents move in to fill a host of new opportunities to “work for wages.” The prior Main Streets confined to a general store, a hostelry and a tavern now add new commercial outlets: banks, restaurants, clothiers, household goods emporiums and even theaters. New York City emerges as the model of success as a marketplace, as evident in its dramatic population gains from 1790 to 1820.

Growth Of Top Ten Urban Centers

| City | 1790 | City | 1820 |

| New York | 33,131 | New York | 123,706 |

| Philadelphia | 28,522 | Philadelphia | 63,802 |

| Boston | 18,320 | Baltimore | 62,738 |

| Charleston | 16,345 | Boston | 43,298 |

| Baltimore | 13,503 | New Orleans | 21,176 |

| No. Philadelphia | 9,913 | Charleston | 24,780 |

| Salem | 7,921 | No Philadelphia | 19,678 |

| Newport | 6,716 | So Philadelphia | 14,713 |

| Providence | 6,380 | Washington DC | 13,247 |

| Marblehead | 5,661 | Salem | 12,731 |

| Average | 14,641 | 39,987 |

But then comes a sudden economic downturn that begins in 1816 and lasts for roughly seven years. The cause is a boom-bust cycle that will be repeated again in 1837 and 1858. It is marked here by rapid speculative investments (the “boom”) to prepare for the War of 1812, followed by the sudden downturn in demand (“the bust”) after the conflict ends.

America’s First Sustained Recession

| Year | 1815 | 1820 | 1825 | 1830 |

| GDP (MM) | $925 | $710 | $822 | $1,022 |

| % Change | +31% | (23%) | +16% | +24% |

Fortunately recovery follows, spurred on by four technological innovations that revolutionize the marketplace:

* Robert Fulton’s Clermont steamboat (1807)

* DeWitt Clinton’s Erie Canal (1825)

* Peter Cooper’s Tom Thumb locomotive (1830)

* Samuel Morse’s Telegraph (1838)

The combination of these innovations have a profound effect on linking supply to demand and developing vibrant urban centers across America.

By 1850, New York City continues to lead the way with over 800,000 in-town residents. But others follow, including new marketplaces along rivers to the west like Cincinnati, St. Louis and Chicago.

Growth In America’s Top Ten Urban Center Marketplaces

| City | 1840 | City | 1850 | City | 1860 |

| New York | 312,710 | New York | 515,547 | New York | 813,669 |

| Baltimore | 102,313 | Baltimore | 169,054 | Philadelphia | 565,529 |

| New Orleans | 102,193 | Boston | 136,881 | Brooklyn | 266,661 |

| Philadelphia | 93,665 | Philadelphia | 121,376 | Baltimore | 212,418 |

| Boston | 93,383 | New Orleans | 116,375 | Boston | 177,840 |

| Cincinnati | 46,338 | Cincinnati | 115,435 | New Orleans | 168,675 |

| Brooklyn | 36,233 | Brooklyn | 96,838 | Cincinnati | 161,044 |

| No Philadelphia | 34,474 | St. Louis | 77,860 | St. Louis | 160,773 |

| Albany | 33,721 | So Philadelphia | 58,894 | Chicago | 112,172 |

| Charleston SC | 29,261 | Albany | 50,763 | Buffalo | 81,129 |

| Average | 88,429 | 145,902 | 271,991 |

By 1860, the benefits of the diversified industrialized economy envisioned by Hamilton and Clay are realized in major increases in the Gross Domestic Product. It stands at nearly $4.4 Billion in 1860, second only to Britain among the leading global powers.

Gross Domestic Product For The United States*

| Year | 1830 | 1835 | 1840 | 1845 | 1850 | 1855 | 1860 |

| GDP (MM) | $1,022 | $1,340 | $1,574 | $1,859 | $2,581 | $3,975 | $4,387 |

| % Change | +24% | +31% | +17% | +39% | +39% | +54% | +10% |

At the same time, the 1860 Census shows that 4 in every 5 Americans still cling to the original American Dream as the Jamestown settlers of 1607: to live and work on their own farms

% Of Population Living In Urban Centers

| Year | Total U.S. | Northeast | Northwest | South | Far West |

| 1820 | 7% | 11% | 2% | 5% | — |

| 1830 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 5 | |

| 1840 | 11 | 19 | 4 | 7 | |

| 1850 | 15 | 27 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| 1860 | 20 | 36 | 14 | 10 | 16 |

But “going into towns and cities” to shop for goods and services has become the norm – and this traffic will change forever the ways that many Americans will make their livings.