Section #2 - Gender Roles

Gender roles

You are there:

True to its Protestant roots and English traditions, America begins as a patriarchal society.

Men are cast as the head of their households and of public affairs in general; women are expected to conform to the subservient roles they are assigned by their fathers and husbands.

Religious beliefs and practices contribute heavily to contemporary views of women – especially the Garden of Eden tale of Eve luring Adam into original sin. For the dominant Calvinist sects such as the Puritans, this forever casts doubt on the moral rectitude of all females. Eternal salvation is in the balance daily, and the prayer – “lead us not into temptation” – is often focused on women and sins of the flesh. (In 1850, author Nathaniel Hawthorne will capture these Puritan tensions in his novel, The Scarlet Letter.)

But women’s subservience at this time extends beyond religious doctrine and into the realm of law.

According to English Common Law, carried over to America, women’s legal rights are established under the principle of “coverture.”

Which means that, once a woman is married (or “covered”), she forfeits her legal rights as an independent person. Thus she is no longer allowed to own property, to sign contracts, or to participate in any business ventures. As the soon to be suffragette, Lucy Stone (1818-1893), will point out…

Coverture gives the custody of the wife’s person to her husband.

A host of orthodoxies regarding both men and women follow from these religious and legal precedents.

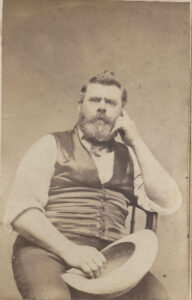

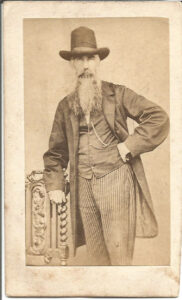

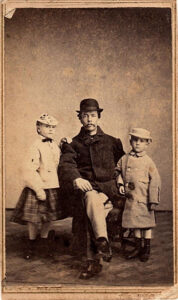

Men are expected to be in charge of their household; to work hard to support their own family’s well-being; and to participate in public affairs, from service in the militia to involvement in politics and government. In all critical decisions facing the family, their word is final.

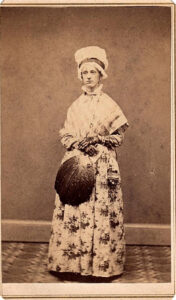

Women too have clearly defined roles in 1820. Since their futures in society is so directly determined by marriage, girls are tutored early on to find a worthy husband. “Proper behavior” is deemed essential here, including the virtues of outward piety, modesty, appropriate dress and manners. Marriages are often “arranged,” and women who fail to land a husband are reduced to “spinsterhood” and probable poverty, left to live at home with their parents.

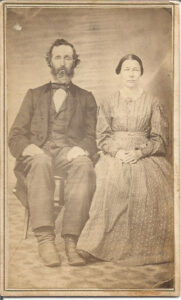

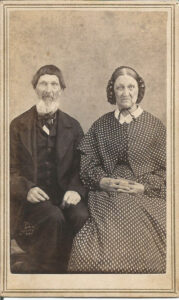

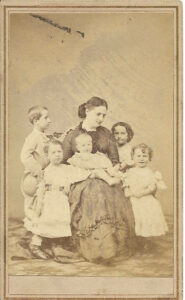

Once married, women are expected to have children, especially male heirs; to raise them properly and contribute to their education; to carry out a multitude of chores associated with maintaining a household; often to help out with farm duties; and to support and obey their husbands. While labeled “the weaker sex,” the physical demands on farm women are often extreme, doubly so since multiple pregnancies and minimal health care are commonplace.

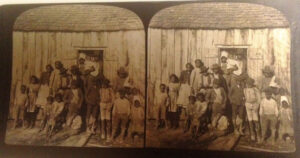

These generalized gender roles are the norm across all regions of the country – although the stereotypes tend to be amplified across segments within the South.

Such deviations are particularly true among the elite planter class in Virginia and the Carolinas, where the culture is prone to mimicking the old world French traditions of chivalry and elegance over the more down to earth mindsets of the English Puritan “Yankees” of New England.

Fragile “Southern belles” placed on pedestals by dashing cavaliers exist, but they are few and far between. The vast majority of females, South and North, are farm women, laboring hard from dawn to dusk to care for their homes and families.

Relatively few women deviate much from their subservient roles.

But some do.

They are helped along as early as 1742, by the opening of the Bethlehem Female Seminary in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Its charter argues on behalf of a revolutionary idea: “when you educate a woman, you educate an entire family.” Its curriculum covers a range of cultural and intellectual topics, spiritual exploration, vocational training and physical exercises. It encourages women’s participation in a range of fields, including education, the ministry and nursing. (It endures today as Moravian College).

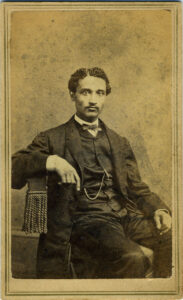

Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) soon picks up the banner. She is a member of the prominent Otis family of Massachusetts and writes political propaganda surrounding the war with Britain. She also corresponds regularly with America’s first three presidents, publishes novels, and befriends another outspoken woman of her time, Abigail Adams.

Adams, of course, becomes the early symbol of a strong and independent women, demanding to have her say in the “affairs of men.” In addition to her role as “first lady” during her husband’s presidency, she engages many of the founding fathers, especially Thomas Jefferson, on public policy. Her written admonition to her husband, John, sets the stage for things to come during the second great awakening of the 1830’s:

Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands, Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have not voice, or Representation.

Advances in education drive the move toward female equality. Instead of “finishing schools” teaching housewifery, reformers like Emma Willard, Catherine Beecher and Mary Lyon open “female seminaries” with curricula that mirror the men’s universities.

Still it will not be until the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention that a small set of educated and determined women band together to publicly challenge the social norms and strive for gender equality. They include Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone among others. Together they formulate their own Declaration of Independence, beginning with a list of their grievances against coverture, and then laying out their set of “resolves” to achieve female rights and equality.

Progress, however, is slow coming and it is not until 1920 that women are granted the right to vote in America!