Section #14 - Entertainment

Entertainment

You are there:

While “work hard to get ahead” is a dominant theme for everyday Americans, various forms of entertainment become available to fill their scarce leisure time.

Prior to the growth of urban centers in the 1820’s, diversions from labor occur mainly on family farms, in the form of various “parlor games.”

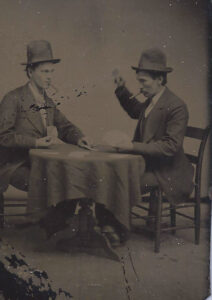

Card games range from the more intellectual and upscale Whist and Eucre to three card draw Poker and, for kids, Old Maid and Snap. Board games like Chess and its simpler cousins, Backgammon and Checkers, appear in the 1850’s. (Ouija boards and the Landlord’s Game, a predecessor to Monopoly, come around 1900.) Other popular parlor games include Charades, Blind Man’s Bluff and Musical Chairs.

Literacy rates are estimated to be upwards of 70% by 1800, with New England leading the way. Thus reading becomes another leisure option, with Bible Scriptures shared out loud and often memorized. The preponderance of popular literature is imported from Europe up until the Revolutionary War when American authors and themes are in the ascendance (see below).

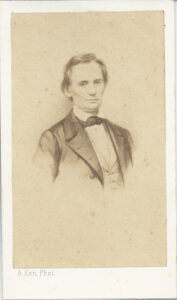

At age eleven in 1820, Abraham Lincoln reads The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, and the Life of Washington. Throughout his life he consumes Shakespeare’s plays while internalizing their cadence in his own writing and speeches.

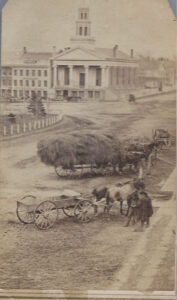

Other early entertainment comes with celebrations. A hay ride to mark the end of the harvesting season. Church-related events: baptisms, weddings, funerals. Simple fiddle music, sing-alongs, and dancing in yards and barns.

Gambling also proves an important pastime from colonial days forward.

One form involves “state lotteries.” Here the government would print up a pre-determined number of “tickets” and individuals would buy them on the hope that their number would be drawn. All tickets are placed in a tub and children draw them out. The total number of “winning” tickets drawn was set in advance, typically around one in five. Of course winners have to pay 20% of their profits to the state as a tax.

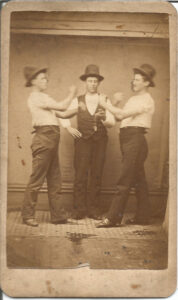

Poker and billiards provide other outlets for gambling, as does traditional cock-fighting, a blood-sport with 50 or more pairs of birds fighting to the death in a ring surrounded by betting observers.

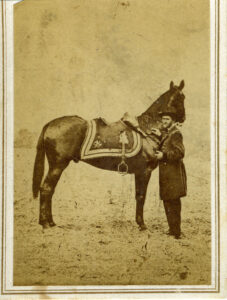

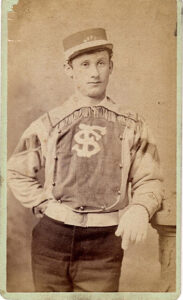

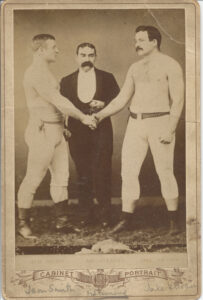

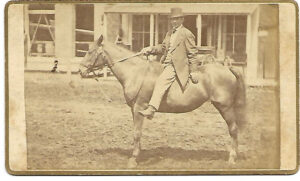

But horse racing is by far the leading sports attraction of the era, decades in advance of future American favorites like: baseball (1869 when the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first professional team), boxing (1882 when John L. Sullivan won the heavyweight title) and football (1892 when Yale’s Pudge Heffelfinger signs the first professional contract).

Horses play an important role in transportation, hunting and herding livestock, and in warfare, where speed is essential to their success. So intrigue as to who owns the fastest horse comes naturally, back to ancient times. By the 17th century in Britain, horse racing emerges as the “Sport of King’s,” with Arabian stallions covering four mile courses in search of cash and trophies and celebrity.

Racing in America is also a rich man’s game, and it begins in 1665 when the English Governor of New York opens an oval racetrack at Hempstead Plains on Long Island. Unlike the four mile endurance contests abroad, Americans often prefer sprints, and they breed “quarter (mile) horses” for that purpose.

At first the competition is between two horses racing to settle a bet between their owners who often serve as jockeys and engage in free-for-all tactics to prevail. This changes in the 1730’s with the advent of jockey clubs and eight horses competing on a mile long track according to formal regulations,

The Revolutionary War is a setback for the racing industry as horses are called upon to resume their role as weapons of war. But the sport rebounds after the victory and jockey clubs expand to the west, with venues in Kentucky and Tennessee surpassing those in Virginia and Maryland.

As of 1800, the Bluegrass State is home to 90,000 horses and the state legislature is forced to pass a stature banning racing in the streets of Lexington for public safety.

Two events are symbolic of early horse racing in America.

One occurs in 1806 after a horse race between Truxton, owned by future President Andrew Jackson, and Ploughboy, belonging to Joseph Erwin, a wealthy cotton planter in Tennessee. Truxton wins the first two out of three heats with a $3,000 wager on the line. But Erwin is upset by the loss and his son-in-law, a lawyer named Charles Dickinson, publicly calls Jackson “a poultroon and a coward.” He also claims that Jackson’s wife, Rachel, was not properly divorced before marrying Jackson. This ends in a duel where Dickinson is killed and Jackson nearly dies of a bullet wound to his chest. All a matter of horse racing, gambling and dueling played out together to a tragic ending.

The second event occurs in 1823 and pits the most famous thoroughbred in the North, nine year old American Eclipse, ridden by William Crafts, against the South’s contender, three year old Sir Henry. The contest is a best two out of three heats with each covering a lengthy four mile dirt track at the Union Racecourse in Queens, New York.

Public gambling on the outcome is unregulated, and consists of side bets among attendees, often shouted out while the race is in progress. American Eclipses loses the first heat, his first ever defeat, but comes back to win the last two against an exhausted opponent. For the victory he wins a prize of $10,000.

But what is amazing about this event is the size of the crowd, some 60,000 spectators, including Senator Andrew Jackson, Aaron Burr and sitting Vice-President, Daniel Tompkins. While owning race horses remains the province of the wealthy, the entertainment value and gambling impulse is enjoyed by all.

Ironically, horses will also play a pivotal role in the origin of theater in America.

The first inklings of theater belong to William Dunlap who opens his John Street venue in 1796 in lower Manhattan. Over the next two decades he produces and acts in over 60 plays, mostly translations of French and German works, along with a few that he writes himself. But commercial success eludes Dunlap and he falls back on his first talent as an accomplished artist.

True theater momentum picks up in 1807 with the arrival in Boston of a traveling Equestrian Circus fresh from a successful tour in Spain. The troupe is owned by two “riding masters,” an American, Victor Pepin, and a Frenchman, Jean Baptiste Breschard, both of whom star in the performances. General admission costs 50 cents for adults and half-price for children. The highlight of the show belongs to Beschard with his “Roman Standing” ride around the ring, one foot on two horses, maneuvering through rings of fire.

Breschard was a model of a performer. He looked like a genteel comedian attired for

a polished drawing-room. He was truly a picture, when dressed in his superb Spanish-lace

uniform, white cassimere small-clothes, silk stockings, neat pumps and gold shoe buckles,

going through his exercise on two horses.

The Pepin and Breschard Equestrian Circus is an immediate hit and completes a six month run at its wooden amphitheater in Charleston, across the Toll Bridge to Boston. It moves on to New York City and then to Philadelphia where its home is the Walnut St. Theater, the first permanent structure of its kind in America. It is built in 1809 and adds a stage and orchestra pit in 1811.

Once in Philadelphia, Pepin and Breschard lay the groundwork for the elaborate circus fare perfected some six decades later by P.T. Barnum and James Bailey. In unexpected fashion they also set the stage for what becomes the nation’s modern theater.

This comes about with their 1809 introduction of “hippodrama,” with their horses and riders assuming the role of actors in choreographed plays. One of their earliest and most popular offerings is Don Quixote de la Mancha, an adaptation of Cervantes’ 1605 novel, featuring his battles and romantic pursuits. Soon enough, however, these horseback dramas are also being performed in the British tradition by human actors on the new stage at Walnut St.

On New Year’s Day 1812, the theater presents Richard Sheridan’s comedy of manners, The Rivals, along with equestrian interludes and a shorter play, The Poor Soldier. Tradition has it that Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette are in the audience to hear Mrs. Malaprop offer her faux pas comments on the heroine, Lydia Languish. Later that same year comes the first American production of a Shakespeare play, in this case, The Winter’s Tale. Henceforth The Walnut playbill would alternate between circus and theater programs.

The success of Pepin and Breshard is not limited to Philadelphia, and theater sites to welcome them appear in New York, Baltimore, Richmond and even New Orleans. And along with these venues comes the need for acts that attract large enough audiences to cover the costs.

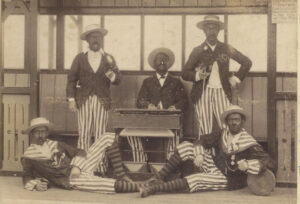

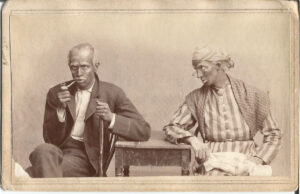

To do so, the American stage stays true to many of its circus-like roots. Playbills featuring “burlesque” promise a steady stream of laughter in skits aimed at exaggerating the foibles of various classes. In some cases these are aimed at the pretentiousness associated with the upper classes. In others, known as “minstrel shows,” the targets are black people.

Minstrel shows involve an ensemble of white actors who paint their faces black and perform skits based on racial stereotypes. Thus all black people are portrayed as dim-witted, lazy, superstitious, happy-go-lucky and prone to petty theft.

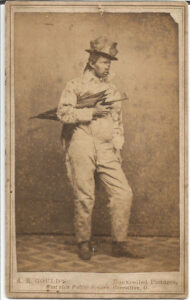

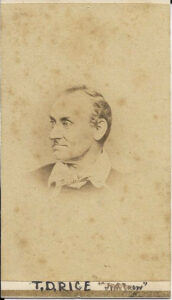

The most famous minstrel show actor in the 1830’s is Thomas D. Rice who achieves fame performing a solo act as the black slave, “Jump Jim Crow.” Rice’s exaggerated use of black vernacular and step dancing routines packs theaters across the U.S. and in Europe and makes him a wealthy man. It also prompts a host of other minstrel groups.

In the mid-1840’s actor Edwin Christy teams up with Stephen Foster, “the father of American song,” to form the Christy Minstrels. The result is a standardized three-part routine that anticipates later-day vaudeville. It opens with a “cakewalk” around the stage ending with three central characters in assigned seating: Mr. Tambo (who plays the tambourine) on the left, Mr. Bones (the banjo) on the right and Mr. Interlocutor in the middle, acting as MC. After a bout of preposterous repartee, comes part two, the “olio,” with various singers, dancers and musicians delivering their riffs. Then the end, often a one act play purporting to show scenes from the lives of “happy slaves” on their plantations.

The popularity of these minstrel shows in both the South and North reveals the appalling depth of anti-black prejudice, disrespect and cruelty dominant at the time.

But ironically they also forever awaken white audiences to the engaging sights of African dance and its accompanying sounds.

One black man who cashes in on this growing popularity is William Henry Lane, who begins to dance in rough and tumble taverns in the Five Points district of New York City. He blends aspects of the Irish jig along with traditional African steps to arrive at his own brand of “Juba Dance” – with feet tapping, legs stomping and hands clapping and patting. This earns him a spot as the only known “authentic black” member of a traveling minstrel show. He also enters “dance contests,” including one in 1844 against the “white champion” John Diamond, possibly arranged by the showman P.T. Barnum. His apparent victory hands him the title of “Master Juba” and credits him as the creator of tap dance in America. He stars in a European tour in 1848 before an early death in 1852 at 28 years old.

The professional dances pioneered in minstrel shows represent new variations from the social options brought over to America by the British colonists. These include the more formal and carefully controlled “minuets” for two dancers and the “cotillions” involving four couples. Both are often accompanied by strings and piano, and are confined to the upper classes.

Although most presidents over time eschew dancing, George Washington and John Adams are known to have taken to the floor regularly on social occasions. In 1823 West Point even decides that proper military offers should be taught to dance as part of the curriculum.

Meanwhile the masses enjoy a wide range of more high energy options. Among the favorites are “line dances” with many participants taking part together. “Contra or Country Dances” begin with two parallel lines and a “caller” sending couples down the middle to the sound of fiddle music, laughter and clapping. “Celtic reels” feature side by side threesomes hop stepping and tapping their way through a series of highly choreographed moves.

Polkas become popular in the 1840’s, first in a slower cadence known as a Scottish Schottische, and then at a more raucous pace. A few years later, a sedate option appears for pairs, the Austrian waltz.

Ballet in America remains in its infancy, despite a rage called “Elsslermania” which sweeps the nation starting in 1840. The celebrity star in this case is Fanny Elssler, a thirty year old native of Vienna who performs at the Paris Opera before agreeing to cross the ocean for a tour that lasts for two years. She earns a remarkable $1,000 a night for dancing at the St. Charles Theater in New Orleans.

America’s first widely recognized ballerina is Mary Ann Lee who is born into a circus family in Philadelphia. Five years after debuting at the Bowery Theater in 1839 she heads to Paris to apprentice under the renowned Swedish ballerina Marie Taglioni, purportedly the first to dance en pointe. Mary Ann returns to the U.S. in 1845, performing Giselle to sold-out crowds.

But in all of its forms, dancing becomes an integral part of entertainment in America.

So too does music which is standard fare in burlesque theater, supported by orchestra pits in venues like the Walnut Street. The public is slow to embrace the orchestral masterpieces of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and the like, despite the existence of a full complement of required instruments: fortepiano, violin, viola, cello, bass, guitar and harpsichord. Instead of the classics, orchestras support minstrelsies, plays, ballet and even opera.

The Beggar’s Opera from London is the first of its kind to become popular with its satirical mocking of the overblown Italian oeuvre. Another comic opera, The Barber of Seville, is a hit in 1825 at the Park Theater in New York City. The first opera by an American composer on a domestic theme is George Bristow’s Rip Van Winkle played in 1830 at Niblo’s Garden Theater in Manhattan

The accepted “father of American song” is Stephen Foster. He receives no formal training but has an uncanny ear for melody, and composes hundreds of popular tunes mainly in the 1850’s. These are sung in home parlors and public venues across America. At minstrel shows, audiences are encouraged to “promenade” around the hall and sing along, accompanied by banjos, fiddles and piano. Foster’s romantic tunes, marked by uncomplicated rhythms and harmony, include these enduring favorites:

My Old Kentucky Home, Camptown Races, Swanee River, Oh! Susanna,

Beautiful Dreamer, Old Black Joe, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair

Foster himself remains almost embarrassed about his chosen profession and never converts his talents into financial success. He dies impoverished at age thirty-seven in 1864.

Along with the growth of burlesque theater comes a host of professional singers, some limited to “fill-in” routines, but a few commanding top billing. Among the latter are the Hutchison Family Singers of New Hampshire who capture the public hearts in the 1840’s with their unique four-part harmony and songs decrying slavery.

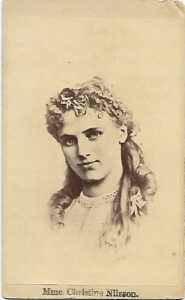

Classically trained singers appear rarely, with most imported from prior fame in Europe. One example is Jenny Lind the 30 year old Swedish soprano sensation brought to America in 1850 by the showman P.T. Barnum. She puts on over ninety concerts for him earning some $350,000 which she donates to charities. Two decades later she is followed by her fellow Swedish operatic soprano, Christina Nillson.

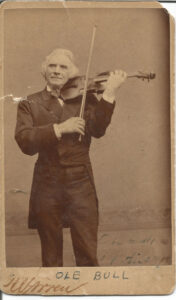

Another European import is the Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, whose talents are said to rival those of Niccolo Paganini. In addition to his stage tours, Bull purchases 11,000 acres of land in Pennsylvania on a visit in 1852. His goal is to found a colony there which he calls New Norway. But little comes of the venture and Bull returns to his violin career. In 1868 at age sixty he falls in love with Sarah Thorp, a twenty year old, and marries her in Madison, Wisconsin. His last concert is in Chicago in 1880

The nation’s early professional pianists serve primarily as background support for various burlesque routines. Only a few attract enough followers to become headliners.

One of them is “Blind Tom” who grows up in Georgia as a slave belonging to James Bethune. While sightless from birth and considered “retarded,” Tom discovers the household piano and begins spontaneously to play the sounds he hears around him. Bethune is astonished, but immediately sees Tom’s “commercial potential.” At age ten his fame spreads after performing at the White House for President Buchanan. Then, over the next fifty years, “Blind Tom” becomes an international favorite. He composes his own music and masters the French horn, the flute and coronet. Among his many feats is a Beethoven concerto which he first plays facing the piano and then facing away with his hands behind his back. Tom dies at age fifty-nine, but his talent is remembered by a fan, the writer Mark Twain, who christens him “an Archangel out of heaven.”

America’s other famous pianist prior to the civil war is Louis Moreau Gottschalk, son of a businessman father and a Creole mother, who grows up in New Orleans and is recognized as a prodigy by age ten. He heads to Europe, where he receives classical training along with praise from the all-time piano master, Frederic Chopin. By the mid 1850’s Gottschalk is back home with the reputation as America’s foremost pianist. His canon includes a series of compositions that capture the unique rhythms of his New Orleans roots and anticipate later day jazz. His most famous pieces are Bamboula (Danse des Negres) and the Creole Ballade La Savane.

Along with the evolution of American theater by 1850 comes celebrity actors. One leading man is Edwin Forrest remembered mainly for his high testosterone portrayal of Spartacus in the 1831 play Gladiator.

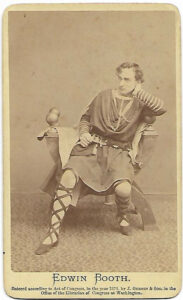

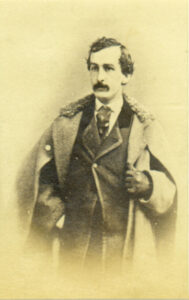

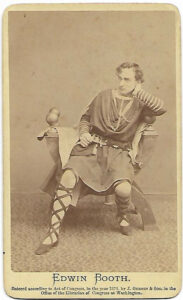

On the distaff side, Charlotte Cushman leverages her vocal range and dramatic talents into diverse roles as Lady MacBeth and Hamlet. But the leading family of actors are the notorious Booths, father Junius and sons Edwin, Junius Jr. and John Wilkes. Edwin rises to the top of the family chart after one hundred consecutive night performing his signature role as Hamlet in Central Park.

For middle class entertainment, however, no one matches the public excitement created by Phineas T. Barnum at his American Museum and later in his traveling circuses. Barnum is born in Connecticut in 1810 and when his father dies he cobbles together enough work as a tailor, shopkeeper, book and lottery auctioneer and newspaperman to support his family.

But his eureka commercial moment comes when he recognizes that his own curiosity about the wonders of the world around him could be brought to life in a new museum of his own making. His first step toward this is the scurrilous “purchase” of a former slave, Joice Heth, whom he “exhibits” during a seven month tour where she claims to be 161 years old, tells stories of her days as George Washington’s nurse and sings hymns for the crowd. As Barnum’s first “curiosity” and first of many hoaxes, Joice establishes his reputation as a showman and, upon her death, some 1500 people pay 50 cents a ticket to watch her autopsy performed in a New York tavern.

In 1835 Barnum American Museum opens on the corner of Broadway and Ann Street in lower Manhattan. Over the next three decades it’s estimated that 22 million visitors will be drawn inside, led by every promotional trick known at the time: newspaper touts, billboards, walk-around bands, oversized painting of jungle animals on the building and jugglers and acrobats outside the front door.

For an entrance fee of only 25 cents the wonders of the world are before their eyes.

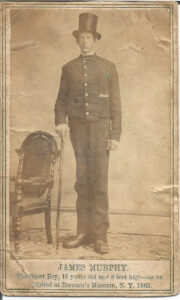

Barnum has uncanny ability to spot one “curiosity” after another. After Joice Heth comes Charles Stratton, a five year old midget born in Connecticut, who is cast as an 11 year old import from England named Tom Thumb, after a well-known fairy tale. He reaches just over 3 feet in height but dresses in General’s gear and imitates Napoleon. He shows off his talents as an actor, singer, dancer and comedian in a range of melodramas. Tom Thumb remains Barnum’s main attraction from 1842 to 1878 and during that time he becomes a wealthy man, touring Europe and India, marrying his wife Lavinia, meeting celebrities from Queen Victoria to Abraham Lincoln. Stratton dies of a stroke at 45 years old.

Barnum is constantly upgrading his museum and adding new attraction. People crowd in to see the “Feejee Mermaid,” upper body of a monkey, lower that of a fish. He adds an aquarium housing two white whales; a replica of Niagara Falls; dog shows, flower shows, beauty contests, rooms full of sea shells, stuffed birds, and Indian artifacts. But the “human curiosities” remain the drivers of success.

In 1850 Barnum introduces high-brow music to America’s middle class with a year-long tour featuring the “Swedish Nightingale,” Jenny Lind. His profits from her performances run to $500,000.

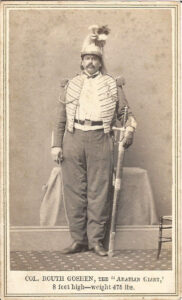

Over time his ensemble will include: the famous Siamese twins, Chang and Eng; the 7’5” 400 lb giant, Routh Goshen; the 7’3” Anna Swan; another little person, Colonel Nutt; the two “wild men of Borneo,” Waino and Plutanor (actually born in Britain and Ohio); Josephine Clofullia the Bearded Lady; the Albino sisters, Florence and Mary Martin; the Four-Legged girl; the Dog-Faced Boy, the limbless Torso Man; his many “moss haired” Circassian Women; the Human Skeleton; and others.

By 1853 critics are calling Barnum the “Prince of Humbug” and his museum a “den of evil.” To counter this, he opens a 3,000 seat “Moral Lecture Room” devoted to high-minded family entertainment and lectures. Anti-slavery sentiments are supported by an Uncle Tom’s Cabin play featuring a happy ending. A temperance play, The Drunkard or The Fallen Saved is performed over one hundred times. Science lectures and other educational enlightenment programs are offered. Barnum is pleased with his “moral efforts” and they actually do anticipate the political “reform agenda” he embraces in 1866-9 as a member of the Connecticut legislature and in 1875 as Mayor of Bridgeport.

Further triumphs and set-backs follow. In 1856 he is bankrupt after an all-in investment in the failed Jerome Clock Company. But he claws his way back with a new attraction, the already famous Siamese twins, Chang and Eng. His pro-Union stance during the Civil War leads to a Confederate sympathizer burning his landmark Museum to the ground in 1864. He dabbles in politics and then, in 1870, meets David Coup, a leading figure in America’s circus history, who convinces Barnum to lend his name to an operation in Delavan, Wisconsin. Coup pioneers the use of trains to expand the reach of his shows. Included here is New York City where the two men open The Great Roman Hippodrome, which later morphs into Madison Square Garden.

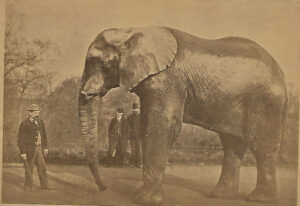

In 1888, the old showman’s last hurrah brings an alliance with James Bailey to form the Barnum and Bailey Circus. Barnum acts as promoter, hyping it as “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Bailey runs all of the day to day requirements. David Coup disappears and dies penniless, while his former partners reap the rewards of their new enterprise. One of their first attractions is London’s famous elephant, Jumbo, standing over ten feet tall and weighing 13,000 lbs. Jumbo joins the circus in 1882 and performs for three years before being killed accidentally in 1885 by a circus locomotive. But Jumbo is Barnum’s final curiosity before he dies of a stroke in 1891 at 80 years old.

The modern circus in America traces its roots not to Barnum or Bailey, but to an Englishman named John Bill Ricketts who opens his Royal Circus and Equestrian Philharmonic Academy in Philadelphia in 1793. He adopts the format pioneered in London by Philip Astley, the acknowledged “father of the circus.” Astley is an expert equestrian who builds a “ring” to showcase his talents. In between his thrilling “Rides Around The Circle” he introduces fill-in performances by acrobats, jugglers, clowns, animal acts, unicyclists, and aerialists. Like Astey, Ricketts is an equestrian, but instead of holding his circus outdoors, he brings his ring indoors until fire claims the theater in 1799. In the interim, both George Washington and John Adams are early attendees.

After Ricketts, leadership of the American circus belongs to the Pepin and Breschard troupe (see above). Another advance comes in 1825 when one Joshua Purdy Brown hosts his act under a canvas tent, initiating the “Big Top” handle and facilitating the movement of the circus from one location to the next. Animal acts become popular in the 1830’s, after Isaac Van Amburgh, dressed as a gladiator, steps into a cage with a lion, tiger and panther. American circuses flourish in the 1850’s, with some 30 different companies scattered across the landscape. For many average folks they become the most exciting form of entertainment available. “Hip-hip-hooray, the circus is coming to town!”

Finally American entertainment of a less social form rests with a wide range of literary offerings.

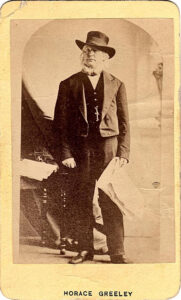

The Newspaper industry flourishes especially in New York City with it “penny press” giants: the New York Sun (1831 and independent); the New York Herald (1835, staunchly pro-Democrat), the New York Tribune (1840 and favoring the Whigs); and the New York Times (1851, a conservative slant). Serious news is accompanied by circulation building coverage of murders, scandals and corruption.

In 1857, the four Harper brothers launch Harper’s Weekly which features biting editorials along with wood-cut illustrations and “bubble cartoons” that provide new visual excitement for its audience

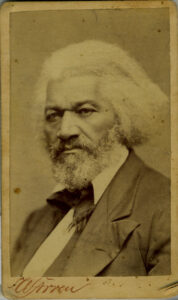

Pamphlets abound, on religion, science, politics and the like, along with a suddenly impressive array of history books, autobiographies (like Fred Douglas’ Narrative), poetry and novels. It is these two latter genres that capture the most public imagination between the Revolutionary and Civil War timeframe.

Literary figures in America emerge in parallel with their contemporary English counterparts. The romantic poets William Wordsworth (1770-1850), Samuel Coleridge (1772-1834), Lord Byron (1788-1824) and Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822). Also the poet laureate during Victoria’s reign, Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-92).The married Brownings, Elizabeth Barrett (1806-61) and Robert (1812-89). Jane Austen (1775-1817) with her six great novels exploring the mores of the landed gentry. The psychological realism of George Eliot (1819-80). The wildly popular characters and tales spun by Charles Dickens (1812-70). The towering romance novels of sisters Charlotte (1816-55) and Emily Bronte (1818-48).

From the beginning, however, America’s poets and novelists play out the scenes and themes that mark their new homeland.

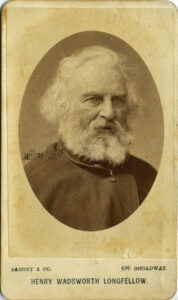

As far back as the 1770’s the remarkable black teen-ager, Phyllis Wheatley (1753-84), is writing poems about morality and slavery. William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) sings of the New England landscape he enjoys on his walks to work, and reflects in Thanatopsis on the sadness of leaving it behind in death. The “fireside poets” include James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier and their leading member, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82) who brings to life the Ojibway warrior, Hiawatha, and the Revolutionary War patriot, Paul Revere. They are joined by the nature worshipping transcendentalists, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-62) and by the unique free verse incantations of Walt Whitman (1819-92) who mixes stark realism with transcendent flights. His ode to Lincoln, O Captain! My Captain! stirs the nation in 1865. Aside from their poetry, these men are also among the nation’s leading intellectuals and are often engaged on civil and political matters.

The most accomplished female poet is Emily Dickinson (1830-86), although she is largely unknown until after her death. Here insights about life and death, hope and despair are simply written but profoundly moving.

While poetry is enjoyed by a segment of the population, America’s early novels enjoy broader reach.

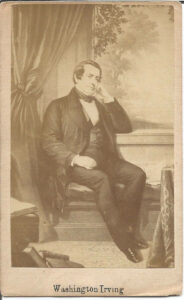

Washington Irving (1783-1859) delivers masterful satire on the foibles of the Dutch founders of Manhattan, writing under the pseudonym of Diedrich Knickerbocker. James Fennimore Cooper wins wider acclaim with his historical novels about the adventures of frontiersman Natty Bumppo in his Leatherstocking series. His portrayal of Natty’s sidekicks in The Last of the Mohicans establishes the favorable imagery of the “noble savage” that endures up to the War of 1812.

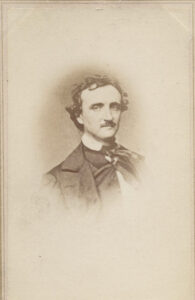

Edgar Alan Poe (1809-49) combines syncopated poetry in his best-selling works like The Raven, Annabel Lee and The Bells, with captivating and macabre stories such as Murders in the Rue Morgue, The Tell Tale Heart, The Cask of Amontillado, and others. As such Poe is credited with inventing detective mysteries.

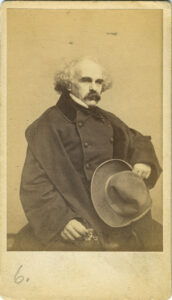

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) explores the dark side of Puritanism in the illicit “romance” between the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale and the liberated Hester Prynne. He follows that with another masterpiece in The House of the Seven Gables, a tale tracing the lives of the Pyncheon family in New England through cycles of sin, revenge and atonement. The novel further establishes the gothic genre, filled with strains of witchcraft, haunted settings, fear and fright.

Joining Poe and Hawthorne in the realm of dark romanticism is Herman Melville with his poem sagas, Typee and Omoo, and his towering allegorical sea adventures, Billy Budd and Moby Dick. These explore the nature of evil in the world and man’s futile obsession with trying to extirpate it for the sake of justice.

But for popularity at the time, no one surpasses the records set by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-96) with her anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Its sales reach 300,000 in its first year and perhaps two million by 1857. Its capacity to spark northern public empathy for those enslaved contributes to the political turmoil at the time. In fact, when Abraham Lincoln meets Stowe, he refers to as “the little lady who started the Civil War.”

Many other male and female poets and authors contribute to the literary scene and create uniquely America themes and styles worthy of a global power.

And that summarizes entertainment in early America!