Section #9 - The Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo: June 18, 1815

French Commoners Storm Bastille Prison And Assert Their Sovereignty

As America is about to embark on its great experiment, “government of the people,” the citizens of France rise up to overthrow their monarchy – which has endured since July 3, 987, when Huge Capet is crowned King of the Franks.

In 1789 the Capetian Dynasty rests with King Louis XVI, who has ascended the throne in 1774, at 19 years old.

Ironically the French Revolution stems from a tax revolt, which mirrors the rebellion in America.

In seeking world dominion over Britain, France has fought two international wars – the disastrous Seven Years War from 1756 to 1763, waged by Louis XV, and the successful “alliance war” with America ending in 1783 at Yorktown. Together they have bankrupted the royal coffers.

King Louis XVI (1754-1793)

The King tries to maneuver his way around the monetary crisis, first by borrowing from abroad, and then by “investing” to stimulate economic growth. Neither strategy works. As the crisis grows, the King’s authority begins to erode.

On May 5, 1789 he is forced to convene the Estates General to seek solutions to the nation’s finances. This body was abolished in 1641 by King Louis XIII, and its assembly now is another signal of growing internal turmoil.

The assembly includes representatives from the three classes of French society:

- The Catholic Clergy (First Estate), some 10,000 strong, exempt from all taxes.

- The hereditary Nobility (Second Estate), 400,000 in number with vast wealth and also no taxes.

- The Commoners (Third Estate), 25 million including the bourgeoisie (middle class property owners), who also avoid taxes, and the vast mainstream of peasants, constantly more squeezed for money.

The convention falls apart before it can even get to the topic of finances – with the Commoners leaving the hall after a series of procedural power plays by representatives of the clergy and nobility.

By June 17, the Commoners have organized their own convention, which they call the National Assembly. They invite the clergy and nobles to attend, but make it clear that they intend to run French affairs with or without them, “on behalf of the people.”

The King steps in to stall this move by shutting down the assembly center, but this only stiffens the will of the delegates. On July 9, they re-convene as the National Constituent Assembly and commit to writing a Constitution for the new government they plan to create.

As the people of Paris take to the streets to express their displeasure, law and order breaks down. The King and the nobles try to rally troops of the French Guard to restore discipline.

On July 12, violent clashes break out, with cavalry units charging into crowds in the center city. This convinces the rebels that a widespread crackdown is about to begin, and they assault various armories and food warehouses around Paris to prepare for battle.

At Hotel des Invalides they acquire muskets, but not the gunpowder needed to fire them. This is stored in the Bastille Prison, which they storm on the morning of July 14. The tide has now turned in favor of the commoners, and they push on toward their own assertion of sovereignty.

The first step comes in the form of a “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” issued on August 20. 1789. This lays out general principles for a constitutional monarchy, leaving King Louis on the throne, but transferring power to a national assembly elected by the people. The country operates this way for the next two years until work on a more detailed Constitution begins in 1791.

For the moment at least, France appears to be headed toward a permanent government run by a legislature similar to the American Congress and the British Parliament.

January 21, 1793

King Louis XVI Is Guillotined And Robespierre Takes Power

From the moment George Washington begins his presidency, global events are about to be dictated by the revolution under way in France.

King Louis XVI’s authority vanishes on July 14, 1789, when the Paris commoners assault Bastille Prison in search of gunpowder to resist local military intervention. But the expectation is for a new government styled after England’s combination of Parliament and a constitutional monarchy.

Despite this prospect, other European monarchs remain deeply shaken by events in Paris.

To the west, the Kingdom of Spain is ruled by Charles IV.

To the east of France lies the Habsburg/Holy Roman/Austrian Empire, ruled by Leopold II (brother of Louie’s wife, Queen Marie Antoinette), comprising territories running from Holland, Belgium, the 300+ middle states of Germany, Austria, Hungary and Croatia/Bosnia.

To the northeast is the Kingdom of Prussia, stretching from the capital in Berlin along the Baltic Sea, under its hawkish monarch, Frederick II.

On August 27, 1791, Leopold II and Frederick I decide to warn the French revolutionaries to not harm the royal family. At first these threats simply exacerbate popular contempt for Louis.

But then the threats grow more dire. On April 20, 1792, the French National Assembly declares war on Leopold and the Habsburgs, and begins an invasion, which quickly draws Prussia into the conflict.

When early battles go against France, a second revolution – called the “Reign of Terror” – sweeps the nation.

It is led by Maximillien Robespierre and far left groups (Jacobins and Sans-Coulettes) who envision a “utopian society” run by the direct voice of the common man and marked by increased wages for all, an end to food shortages, and punishment meted out to nobility.

On August 10, 1792, Parisian’s attack the King’s palace and place him and his family under house arrest. He is tried before the National Convention, convicted of treason, and sentenced to death. On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI, is driven through Paris in his carriage, arriving at the Place de la Revolution around 10AM. The final act is described by the High Executioner, Charles-Henri Sansone, who oversees some 3,000 such events in his day, and becomes known as “Monsieur de Paris” for his exploits.

Maximilien de Robespierre (1758-1794)

Arriving at the foot of the guillotine, Louis XVI looked for a moment at the instruments of his execution and asked Sanson why the drums had stopped beating. He came forward to speak, but there were shouts to the executioners to get on with their work. As he was strapped down, he exclaimed “My people, I die innocent!” Then, turning towards his executioners, Louis XVI declared “Gentlemen, I am innocent of everything of which I am accused. I hope that my blood may cement the good fortune of the French.” The blade fell. It was 10:22 am. One of the assistants of Sanson showed the head of Louis XVI to the people, whereupon a huge cry of “Vive la Nation! Vive la République!” arose and an artillery salute rang out which reached the ears of the imprisoned Royal family.

With the King now dead and war in progress, pressure rises on the National Convention to take charge of the nation’s destiny. This will involve a new battle between the bourgeoisie (middle class) and the proletariat (lower classes).

Robespierre steps up to the challenge as head of the Committee of Public Safety. He calls on France to create a “Republic of Virtue,” run by the common man, and based on concepts laid out by Rousseau.

Included here was the “Cult of the Supreme Being.”

Is it not He who decreed for all peoples liberty, good faith and justice? He did not give us priests to harness us to the chariots of kings and to give us examples of baseness, pride, perfidy, avarice, debauchery and falsehood. He created men to help each other, to love each other, to attain happiness by way of virtue.

Anyone standing in the way of Robespierre’s vision needs be dealt with quickly and harshly – and roughly 16,000 “aristos” or other enemies are publicly guillotined to purify the nation.

Included here, on October 16, 1793 is Louis’ wife, Marie Antoinette.

The French Revolution: Key Events – 1789-1793

| 1789 | Financial crisis over cost of American war triggers increased taxation |

| Troops put down riots over low wages and food shortages | |

| Citizens storm Bastille (July 14), symbol of monarchy | |

| Great Fear begins, peasants revolt against feudalism and aristos | |

| Assembly adopts Lafayette’s Declaration of the Rights of Man | |

| 1790 | Nobility abolished by National Assembly |

| 1791 | Lafayette orders arrest of 400 aristocrats |

| Massive slave revolt in French colony of Haiti | |

| 1792 | France declares war on Leopold II’s Habsburg monarchy (April 20) |

| Frederick II and the Kingdom of Prussia joins Leopold’s side | |

| Tuileries Palace stormed and Louis XVI imprisoned | |

| 1793 | Louis Capet XVI is guillotined (Jan 21) |

| Jacobin Party and Robespierre take control of the government | |

| France declares war on Britain and Holland (Feb 1) | |

| France declares war on Spain (March 7) | |

| Girondist (moderate) faction expelled from National Assembly | |

| Robespierre’s Reign of Terror begins (September 5) | |

| Marie Antoinette guillotined (Oct 16) |

Time: 1794-1799

Robespierre Is Overthrown And Napoleon Becomes A National Hero

The proletariat Reign of Terror in France, now at war with most of its neighbors, plays itself out roughly five years after it begins.

When Robespierre uses his power to eliminate his political rivals, often without any form of trials, those around him finally sense that no one is safe. They arrest and behead him, face up, on July 28, 1794.

At this point, the Revolution enters its second stage, lasting from 1794 to 1799.

The Constitution of 1795 is approved, and establishes a government consisting of 750 legislators led by a rotating “Executive Directory” of five senior men, one retiring each year.

Not all factions support this outcome, especially the pro-Catholic forces who resent the Revolution’s virulent attacks on the church. They band together with Royalist forces and march on Paris with a force of 30,000 men, including 2,000 troops from Britain.

The Directory is ill prepared to counter this threat.

In desperate straits, they turn to a 26 year old artillerist, recently promoted to Brigadier General for his daring campaign in December 1793 that drives the Royalists and British out of the Mediterranean port city of Toulon.

The soldier’s name is Napoleon Bonaparte..

On October 5, 1795, Napoleon assembles 40 cannon, places them strategically throughout Paris, and fires grape-shot into the Royalist troops, routing them despite being outnumbered by 6-1 in man-power.

For this feat, Napoleon immediately become a national hero. He has calmed the internal struggle for power within the French capital, and now turns his attention to the foreign wars under way beyond its borders. He is named Commander of the Armee d’Italie, and heads off to win four years’ worth of victories abroad.

On November 10, 1799 he will return to Paris, stage a coup that ends the “Revolutionary period,” and makes himself First Counsel and head of the French Republic.

The French Revolution: “Second Stage” – 1793-1795

| 1792 | France declares war on Leopold II’s Habsburg monarchy (April 20) |

| Frederick II and the Kingdom of Prussia joins Leopold’s side | |

| Tuileries Palace stormed and Louis XVI imprisoned | |

| 1793 | Louis Capet XVI is guillotined (Jan 21) |

| Jacobin Party and Robespierre take control of the government | |

| France declares war on Britain and Holland (Feb 1) | |

| France declares war on Spain (March 7) | |

| Girondist (moderate) faction expelled from National Assembly | |

| Robespierre’s Reign of Terror begins (September 5) | |

| Marie Antoinette guillotined (Oct 16) | |

| Napoleon wins fame at Siege of Toulon (Dec 18) | |

| 1794 | Robespierre arrested and guillotined (July 28) |

| The Executive Directory (5 men) takes control of government | |

| 1795 | Napoleon Bonaparte quells Paris insurrection (October 5) |

| 1799 | Napoleon rules France as First Counsel |

Between 1799 and 1815 Napoleon’s France will largely dictate the fate of nations across the globe.

Time: May 2, 1803

Jefferson Doubles America’s Land Mass With His Louisiana Purchase

With Leclerc’s efforts against Saint-Domingue in motion, Napoleon looks toward America, and begins to test its will. He begins by ordering his Spanish surrogate administrator to shut-down the port of New Orleans to U.S. shipping, on October 16, 1802. He also assembles an army in Holland intended for a probe into America.

Jefferson and his advisors are fully alarmed at this point.

On May 29, 1801 – some 16 months after the fact – the American minister to France, Robert Livingston, informs Jefferson of a rumor that Napoleon has reacquired Louisiana.

Jefferson can easily imagine how his aspirations to expand westward would be impacted by hostile French forces lining up along his new western seacoast, the Mississippi River, and closing the port of New Orleans, the emerging hub of all commerce on the frontier. His reaction is telling:

There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans.

Unlike Touissant, he acts swiftly to deter Napoleon. He vigorously protests the shipping restraints and then, in March 1803, sends his trusted friend, James Monroe, to France with approval to spend up to $9 million to try to buy the crucial port of New Orleans, along with West Florida.

By the time Monroe arrives, however, the situation has changed for Napoleon.

The Saint-Dominque intervention, which started so well, has begun to fall apart.

This set-back, along with the complexities of planning for the invasion of Britain, dampens Napoleon’s interest in any immediate action against America. Instead he decides that France is best served by taking America’s money and encouraging her to join in the fight against British, with her developing naval power.

So, when Monroe arrives, Napoleon’s surrogates, Talleyrand and Marbois, signal their willingness to discuss a purchase – not only of New Orleans, but of the entire Louisiana Territory.

Jefferson, ever the western expansionist, jumps at the opportunity. On May 2, 1803, American Ambassador Robert Livingston agrees to buy 827,000 square miles of land from France for $15 million, or roughly 3 cents/acre.

The President sees the Louisiana Purchase as “land for the next twenty generations” of American farmers, the key to the agrarian ideal in his vision.

Napoleon shrugs off the deal as a momentary set-back. He will use the money to defeat the British and then re-visit America at a later date, if he decides to take it.

Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase: Key Events

| 1697 | Spain cedes Saint-Dominque to France |

| 1756 | The Seven Years War (“first world war”) pits Britain vs. France/Spain |

| 1762 | France “unloads” Louisiana on Spain |

| 1763 | Treaty of Paris ends The Seven Years War, with Britain victorious |

| 1781 | America wins its war with Britain |

| 1794 | Jay’s Treaty with Britain: abandon forts for fur-trading rights |

| 1780 | Saint-Dominique slave plantations dominate sugar and coffee production |

| 1791 | Slave revolt leaves Toussaint Louverture in control of St. Dominque |

| 1799 | Napoleon assumes power in France as First Counsel |

| 1800 | Spain gives Louisiana back to France in secret Treaty of San Ildefonso |

| 1801 | America learns that France again owns Louisiana |

| Ambassador Robert Livingston begins negotiations with Talleyrand | |

| 1802 | In January LeClerc lands in San Dominique with 20,000 troops |

| Toussaint is lulled into captivity and sent back to a French prison to die | |

| Yellow fever decimates the French troops and kills LeClerc | |

| 1803 | Monroe arrives with $9 million to try to buy New Orleans |

| Napoleon begins to plan invasion of Britain | |

| The US acquires the entire Louisiana territory for $15 million | |

| Jefferson sends Lewis and Clark off to explore the new land | |

| 1804 | Dessalines drives the French out and names himself Emperor |

| 1805 | Horatio Lord Nelson defeats a French invasion fleet at Trafalgar |

Time: 1803

After Fiery Debate Congress Approves The Purchase

Ironically, in agreeing to buy Louisiana, Jefferson oversteps the limitations on Executive power he has tried so hard to impose in his Tenth Amendment and in the “Kentucky Resolutions” of 1798 where he calls for “nullification” of Adams’ Sedition Acts.

The result is a firestorm of opposition in Congress.

While the Senate is upset by Jefferson’s unilateral activities, it does ratify the Louisiana Treaty on October 20, 1803, some five months after the deal was agreed to in Paris.

The House, however, is a different matter. It controls the nation’s purse strings, and is determined to demonstrate its prerogatives in this regard. It hurls a series of challenges Jefferson’s way.

Some question whether France even owns Louisiana, or whether it still belongs to Spain.

Others ask about the boundaries of the territory and the number of new states it might generate – only to find that precise answers are lacking.

Easterners are immediately concerned that opening this much new land will eventually erode their power in the Congress – and go so far as to suggest that such a deal actually violates the original contract of 1787.

The debate also touches on the issue of slavery. The 1787 Northwest Ordnance and the 1790 Southwest Ordnance have delineated the Ohio River as the demarcation line for slavery, out to the Mississippi River. But what about the new land to the west of the Great River – will it allow slavery or not?

Jefferson is surprised by the opposition to an acquisition that seems so obviously right to him. In response he ponders the need for a constitutional amendment to justify the deal, but soon dismisses the idea.

Finally a House resolution to reject the Louisiana Purchase fails to pass by a slim majority of 59-57.

On October 29, 1803, the House passes an appropriations resolution giving Jefferson the go-ahead he wants.

Upon completion of the purchase, America now owns 56% of its eventual east to west coast land mass. The remainder is in the hands of Spain.

America’s Acquisition Of Land

| Year | Land Gained | From | Via | Square Miles | % US |

| 1784 | 13 colonies to Miss R | Britain | War | 888,811 | 29% |

| 1803 | Louisiana Territory | France | Buy | 827,192 | 27 |

December 4, 1804

Napoleon Crowns Himself Emperor And Resumes War With Britain

On December 2, 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte establishes hereditary power over France for his family, as he crowns himself Emperor at Notre Dame Cathedral.

The service is designed to mimic the standards set for royal successions across Europe.

To insure that Napoleon will reign “in the eyes of God,” Pope Pius VII attends the ceremony in person. The 62 year old pontiff has been in office for four years, and is intent on restoring the Church’s standing in France after seeing papal authority stripped away during the people’s revolution. His first step here is the Concordat of 1801, negotiated with Napoleon as First Counsul, which recognizes Catholicism as the “religion of the great majority” in France, while dropping claims to church lands seized during the overthrow of the old order.

Napoleon enters Notre Dame after Pius is already seated. He arrives with his wife, Josephine, in a carriage drawn by eight horses. He is gowned up in an eighty pound coronation mantle, supported by four manservants, and embroidered with “golden bees,” which he favors over the traditional fleur-de-lis symbol for France.

When the moment comes for the Pope to crown him, Napoleon intercedes by placing the laurel wreath on his own head and repeating the act for Josephine as Queen. Pius then intones his blessing:

May God confirm you on this throne and may Christ give you to rule with him in his eternal kingdom.[

The action is completed with Napoleon placing his hands on the Bible and declaring his civil oath of office.

I swear to maintain the integrity of the territory of the Republic, to respect and enforce respect for the Concordat and freedom of religion, equality of rights, political and civil liberty, the irrevocability of the sale of national lands; not to raise any tax except in virtue of the law; to maintain the institution of Legion of Honor and to govern in the sole interest, happiness and glory of the French people.

As absolute monarch he is now eager to turn his energy against fulfilling the “glory of the French people.”

His sights, as always, are on the British, and reversing the losses suffered four decades ago in the Seven Year’s War. He will attack them on land and sea, along with any confederates who join them.

The days of French ascendance have arrived.

| La Marseillaise (1792) | |

| French lyrics | English translation |

| Allons enfants de la Patrie, | Arise, children of the Fatherland, |

| Le jour de gloire est arrivé! | The day of glory has arrived! |

| Contre nous de la tyrannie, | Against us tyranny’s |

| L’étendard sanglant est levé, (bis) | Bloody banner is raised,(repeat) |

| Entendez-vous dans les campagnes | Do you hear, in the countryside, |

| Mugir ces féroces soldats? | The roar of those ferocious soldiers? |

| Ils viennent jusque dans nos bras | They’re coming right into our arms |

| Égorger nos fils, nos compagnes! | To cut the throats of our sons, our women! |

| Aux armes, citoyens, | To arms, citizens, |

| Formez vos bataillons, | Form your battalions, |

| Marchons, marchons! | Let’s march, let’s march! |

| Qu’un sang impur | Let an impure blood |

| Abreuve nos sillons! (bis) | Water our furrows! (Repeat) |

Time: 1715 – 1855

Sidebar: Roll Call Of Key 18-19th Century Foreign Monarchs

| France | Begins Reign | Ends Reign |

| Louis XV | Sept 1, 1715 | May 10, 1774 |

| Louis XVI | May 10, 1774 | Sept 21, 1792 |

| First Republic | 1792 | 1804 |

| Napoleon I | May 18, 1804 | April 11, 1814 |

| Louis XVIII | April 11, 1814 | March 20, 1815 |

| Napoleon I | March 20, 1815 | June 22, 1815 |

| Napoleon II | June 22, 1815 | July 7, 1815 |

| Louis XVIII | July 7, 1815 | Sept 16, 1824 |

| Charles X | Sept 16, 1824 | Aug 2, 1830 |

| Louis-Phillipe I | August 9, 1830 | Feb 24, 1848 |

| Second Republic | 1848 | 1852 |

| Napoleon III | Dec 2, 1852 | Sept 4, 1870 |

| England | ||

| George II | June 11, 1727 | Oct 25, 1760 |

| George III | Oct 25, 1760 | Jan 29, 1820 |

| George IV | Jan 29, 1820 | June 26, 1830 |

| William IV | June 26, 1830 | June 20, 1837 |

| Victoria | June 20, 1837 | Jan 22, 1901 |

| Spain | ||

| Charles III | Aug 10, 1759 | Dec 14, 1788 |

| Charles IV | Dec 14, 1788 | March 19, 1808 |

| Ferdinand VII | March 19, 1808 | May 6, 1808 |

| Joseph I | May 6, 1808 | Dec 11, 1813 |

| Ferdinand VII | Dec 11, 1813 | Sept 29, 1833 |

| Isabella II | Sept 29, 1833 | Sept 30, 1868 |

| Prussia | ||

| Frederick I | January 18, 1701 | February 25, 1713 |

| Frederick William I | February 25, 1713 | May 31, 1740 |

| Frederick II (Great) | May 31, 1740 | Aug 17, 1786 |

| Frederick-William II | Aug 17, 1786 | Nov. 16, 1797 |

| Frederick William III | Nov. 16, 1797 | June 7, 1840 |

| Federick William IV | June 7, 1840 | Jan 2, 1861 |

| Russia | ||

| Catherine The Great | July 9, 1762 | Nov 17, 1796 |

| Paul I | Nov 17, 1796 | Mar 23, 1801 |

| Alexander I | Mar 23, 1801 | Dec 1, 1825 |

| Nicholas I | Dec 1, 1825 | Mar 2, 1855 |

| Alexander II | Mar 2, 1855 | Mar 13, 1881 |

Time: October 21, 1805

Napoleon’s Momentum Is Hindered Momentarily By Lord Nelson At Trafalgar

By the late summer of 1805, Napoleon has completed his plan to invade the British Isles, and has assembled a naval armada of French and Spanish ships to support the attack. But the invasion is delayed after Austria and Russia enter the war. Still, Napoleon is displeased by the lack of aggression he sees in the commanding officer of his fleet, Admiral Pierre-Charles de Villaneuve, who learns that he is about to be relieved.

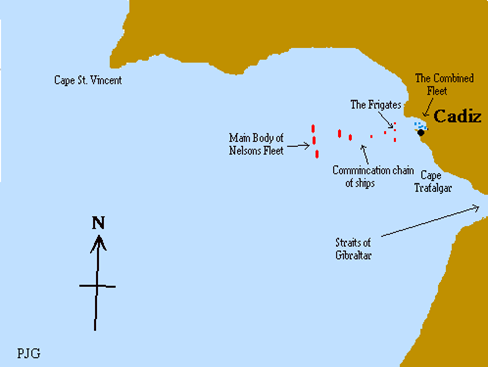

On October 20, 1805, before his replacement can arrive, Villaneuve departs the port of Cadiz on the southwest coast of Spain, intending to sail south past Cape Trafalgar and the Straits of Gibraltar, into the Mediterranean and the French port of Toulon.

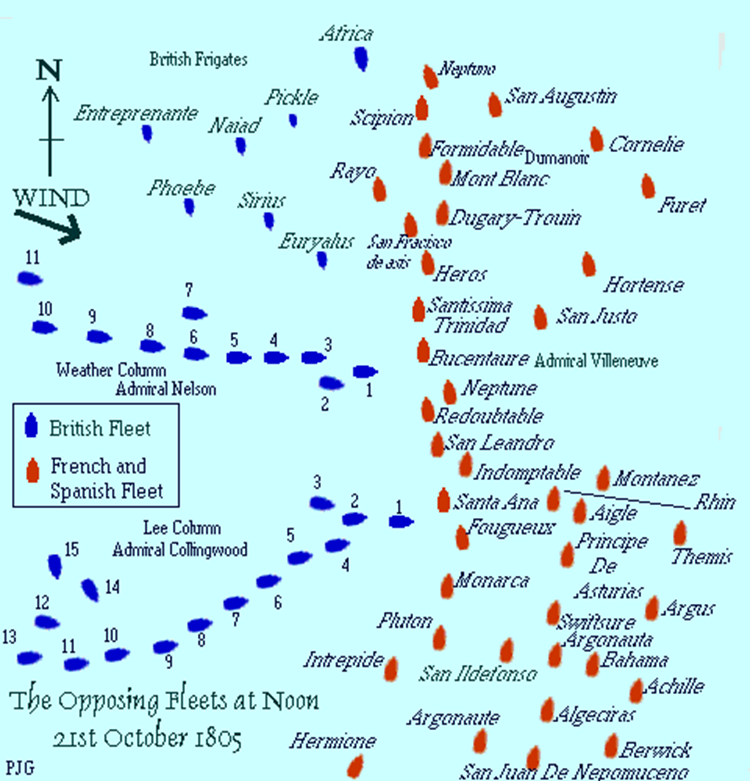

Villaneuve’s fleet is formidable, comprising 33 heavy duty warships, with some 30,000 sailors and 2,568 guns.

At 11AM on October 21, they encounter the British navy, under the command of Captain Horatio Nelson, aboard his HMS Victory.

Nelson is already a legend within the Royal Navy. He enlists as an Ordinary Seaman at age twelve, serving under his uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling, who turns him into a first rate sailor, despite his lifelong bouts of seasickness. By December 1778, age twenty, he is Master and Commander of the sloop HMS Badger. He is engaged briefly around Boston and New York during America’s Revolutionary War, then becomes a national hero in February 1797, after capturing two Spanish warships at the Battle of St. Vincent.

He is almost killed on multiple occasions. In 1794 enemy shot leaves him blinded in his right eye. On July 24, 1797, his left arm is shattered by a musket ball while leading a failed landing party assault on the Canary Island city of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Amputation follows. In 1798 Nelson is knocked unconscious by shrapnel during the victorious Battle of the Nile. Afterwards he is awarded the honorary titles of Baron and Viscount.

On October 21, 1805, Nelson has been battling the British and French off and on for some twelve years. He is 47 years old and Vice Admiral of the White (ensign) Fleet, second highest command in the Royal Navy. He has 27 warships at his disposal, with 17,000 men and 2,148 guns.

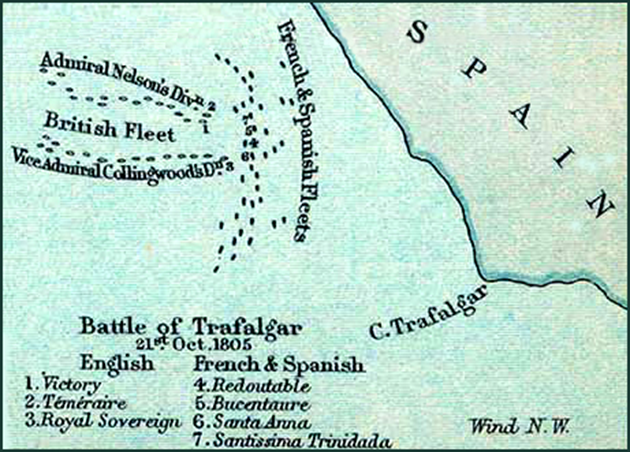

At 8AM the two fleets spot each other from a distance, the French still heading south toward Gibraltar, the English coming at them from the west. Villaneuve order his four-masters “to wear” (or jibe), reversing course to head back to Cadiz. But Nelson keeps coming onto him. The famous command — “England expects that every man will do his duty”—is flagged up.

Around noon, the ships close on one another, with traditional naval strategy calling for Nelson to turn and “form lines of battle” stations parallel to the enemy. Instead, he plows straight ahead, striking the French in perpendicular fashion, and bringing on a “pell-mell” series of ship against ship action favorable to his more skilled seaman. This move, executed at no small risk of receiving initial broadside fire, also allows him to shoot into the sterns of many French ships, with the fire traveling through the entire length of the ship, to the bow.

Nelson himself commands the lead ship, HMS Victory, into the fray.

Greater Detail on Nelson’s Straight on Line of Attack

British Line Of Battle

| Weather Column | Lee Column |

| Victory | Royal Sovereign |

| Temeraire | Bellisle |

| Neptune | Colossus |

| Leviathan | Mars |

| Conqueror | Tonnant |

| Agamemnon | Bellerophon |

| Britannia | Achille |

| Ajax | Polyphemus |

| Orion | Revenge |

| Minotaur | Swiftsure |

| Spartiate | Defence |

| Thunderer | |

| Defiance | |

| Prince | |

| Dreadnought |

As Victory locks with the French Redoubtable, a musket ball takes Nelson in the left shoulder, slices through his seventh cervical vertebrae and lodges in his right shoulder. He knows immediately that the wound is fatal, and says so to his surgeon.

You can do nothing for me. I have but a short time to live. My back is shot through.

He lingers below decks for another 3½ hours, still issuing orders, before succumbing to his wound. His last words are recorded as “Thank God I have done my duty.”

And his victory at Trafalgar is striking. Villaneuve’s fleet has suffered one ship sunk, seventeen ships captured, another eleven partially damaged and only four escaping unscathed. Some 4,500 of their seamen are killed, with another 2,400 wounded and 7,000 taken prisoner. On the British side, no ships are lost for good and total dead and wounded total 1,450.

The Royal Navy has again demonstrated its supremacy on the high seas, and Napoleon casts aside all thoughts of an invasion of the English Isles.

Despite this, Britain mourns the loss of its most famous admiral. His body is packed inside a cask of brandy and other agents for preservation. This is towed home alone with his wounded ship, Victory. On January 9, 1806, England’s most famous naval figure is interred at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

December 2, 1805 – October 14, 1806

On Land, The French Win One Major Battle After Another

Napoleon is characteristically undaunted by the loss at Trafalgar.

On December 2, 1805, in the nine hour “Battle of The Three Kings” – near Austerlitz (now in the Czech Republic) — his undermanned force (73,000 vs. 86,000) pulls a stunning victory against Alexander I of Russia and the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. Casualties for the day total a staggering 36,000 men. In response to the loss, Francis gives up his Holy Roman title and becomes simply King of Austria.

Less than a year later, on October 14, 1806, Napoleon soundly defeats the 110,000 man Prussian army, in the two-part battle of Jena-Auerstadt, winning control over territory in what is now central Germany and Poland. Casualties here are even greater than at Austerlitz, totaling 50,000 soldiers.

France Extends its Borders as Napoleon Emerges Victorious

With these two pivotal triumphs, he now effectively controls all of Europe, except for Portugal, and he again moves against the British by imposing a Continental Blockade halting all trade with England in his Berlin Decree, issued on November 21, 1806.

Napoleon’s Early Campaigns

| 1792 | 1st Coalition War vs. Austria and Prussia (end 1797) |

| 1793 | Siege of Toulon (southern France) – Napoleon wins first fame |

| 1795 | N quells pro-monarchy insurrection in Paris |

| 1797 | First Italian campaign (victories at Lodi and Arcola) |

| 1798 | Expedition to Egypt and Syria |

| 1799 | N seizes power in Paris as First Counsul of the Republic |

| 2nd Coalition vs. Russia, UK, Austria, Naples, Vatican, etc (end 1802) | |

| 1800 | Second Italian campaign (victory at Marengo (nw Italy) over Austria |

| Spain trades Louisiana Territory back to France for Tuscan land | |

| France ends its Quasi-War with the US | |

| 1802 | Treaty of Amiens ends war with Britain (for one year) |

| N expanding his power over France | |

| 1803 | Britain declares war on France |

| 1804 | 3rd Coalition vs. Britain, Austria, Prussia |

| 1805 | Napoleon crowns himself Emperor of France |

| 1805 | British defeat French invasion fleet at Trafalgar |

| Battle of the Three Kings at Austerlitz – N beats Austria and Russia | |

| 1806 | 4th Coalition vs. Prussia and Russia |

| Battle of Jena-Auerstedt – N beats Prussia |

Time: 1808 – 1811

Napoleon Controls All Of Europe By 1811

The war that Madison proposes in 1812 results directly from the existential threats posed to Britain by the Emperor Napoleon of France. Thus the need to interfere with American ships and “impress” American sailors in order to man the Royal Navy to stop a French invasion.

Ironically, just as America and Britain are about to go to war again, Napoleon begins his fateful plunge into the Russian homeland which eventually ends his stranglehold on world affairs.

The new French empire continues to ride high into 1806, controlling all of central Europe except Portugal.

When Portugal resists, the French and their ally, Spain, invade, capturing Lisbon on December 1, 1807, as the royal family transfers their regency to the colony of Brazil.

Further intrigue follows in February 1808, as Napoleon makes a move he has long avoided, turning against Spain. The betrayal catches the Spanish army by surprise and it quickly gives way. However, bloody public uprisings occur in many cities, including Madrid, and lead on to the reprisal executions later immortalized by the artist, Goya. It is not until May 5, 1808, that Napoleon is able to name his older brother, Joseph, King of Spain.

While the local Spanish population refuses to bend to the French will, and guerilla “(“little war”) actions persist over time, supported in part by British expeditionary forces, Joseph is able to remain on the throne until the tide turns against the French in 1812-13.

To the East, the Austrian monarch, Francis II, loser at Austerlitz, decides to challenge Napoleon once again. He does so in 1809 at Wagram, 6 miles northeast of Vienna, in a fierce artillery dominated battle that covers July 5-6, involves 300,000 men, and counts 80,000 casualties – with the French once again emerging victorious.

By 1810, Napoleon’s power is at a zenith.

He has effectively isolated Britain from its three potential “coalition partners” on the continent – Austria, Prussia and Russia – by thrashing their armies and by signing peace accords with each.

The only things limiting France’s horizons are the presence and superiority of the British navy – and the small chance that Napoleon will eventually make a strategic blunder.

Napoleon’s Triumphs In 1807 To 1811

| 1807 | Battle of Friedland – Napoleon beats Russia |

| Peninsular campaign – Napoleon beats Portugal | |

| 1808 | Napoleon turns on ally Spain, Joseph Napoleon on throne |

| 1809 | 5th Coalition vs. Austria and Britain |

| Battle of Wagram – Napoleon beats Austria, occupies Vienna | |

| Napoleon divorces Josephine; marries Marie-Louisa of Austria seeking heir | |

| 1810 | Napoleon and France rule the European continent |

| 1807 | Battle of Friedland – Napoleon beats Russia |

| Peninsular campaign – Napoleon beats Portugal | |

| 1808 | Napoleon turns on ally Spain, Joseph Napoleon on throne |

| 1809 | Battle of Wagram vs. 5th Coalition including Austria and Britain |

| Napoleon divorces Josephine; marries Marie-Louisa of Austria seeking heir | |

| 1811 | Napoleon and France rule the European continent |

Time: June to December 1812

Napoleon Suffers A Crushing Defeat In Russia

In June 1812 Napoleon makes the strategic mistake that will cost him his empire.

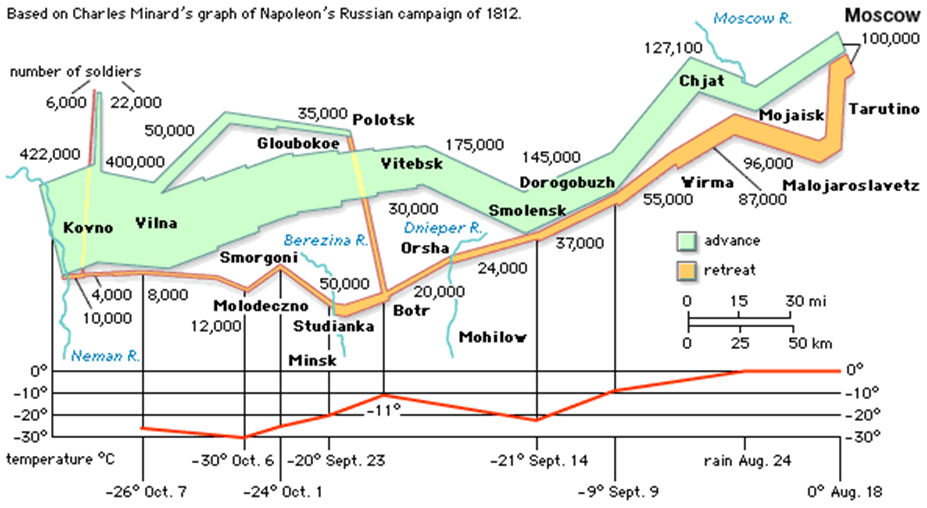

When Russia, encouraged by Britain, withdraws from Napoleon’s continental blockade of English goods, the Emperor decides to invade. He assembles a huge army, over 400,000 men (half French, half foreign conscripts), and begins to march east on July 24, 1812. The Russians at first retreat, under the scorched earth strategy of the Scotsman, Barclay de Tolley, Minister of War. When troop morale deteriorates, command passes to the 67 year old veteran, General Mikhail Kutuzov.

Kutuzov has suffered two horrible head wounds over time, which leave his right eye mis-shapened and cause him constant pain. He has also fought Napoleon before, losing at Austerlitz, which leads Alexander I to doubt his talents. But Kutuzov is a native Russian, much beloved by the troops, and he is charged with resisting the French approach to Moscow.

By the time Napoleon is ready to attack, the strength of the central army wing under his direct command has already dwindled sharply, from a combination of battles, winter cold, dysentery and typhus.

At 5:30AM on September 7, his remaining 130,000 men attack Kutuzov’s 120,000 troops just west of Borodino, some 65 miles from Moscow. Both generals blunder during the day, Kutuzov’s troop deployment is flawed and Napoleon refuses to send his Old Guard in to finish off the battle – which turns into a bloodbath, with French losses at 30,000 and Russian losses at 44,000.

After Kutuzov retreats, Napoleon continues his march to Moscow, reaching the city on September 14. By that time, however, only 15,000 of the city’s population of 270,000 have stayed behind, the mayor has put the torch to most of the buildings, and both food and shelter are in short supply.

Napoleon is now some 1500 miles from Paris and 600 miles from his jumping off point for the invasion, the Nieman River, in Poland. What was the Grande Armee 400,000 strong in July has been reduced to 95,000 tired and starving men eight weeks later.

When Alexander refuses to discuss a treaty to end the conflict, Napoleon exits Moscow on October 19. The road back west is tortuous and marked by death from ambushes, starvation and disease. While various commanders cite the winter weather as a sizable factor in the defeat, the first snowfall is not recorded until November 5 and temperatures tend to hold in the 15-20 degree Fahrenheit range until early December.

On December 14, 1812, the survivors of the Russian campaign re-cross the Nieman. Most estimates peg this number at around 30,000 men.

In less than five months Napoleon has lost over a quarter million dead and wounded and another 100,000 captured. He has lost Russia. And he has forever lost his mantle of invincibility.

Invasion of Russia.

Time: Summer 1812 – Winter 1813

France Is Driven Out Of Spain

While the military tide in 1812 is turning against Napoleon himself in the east, it is likewise threatening his brother Joseph’s rule in Spain.

The main source of the western threat is none other than the Irishman, Arthur Wellesley, destined for future fame as the Duke of Wellington. Wellesley is born into wealth in 1869, educated at Eton, and travels to France to learn horsemanship and to speak French. He wishes to pursue his love of music, but his mother pushes him into the military. He serves multiple tours of duty with the British army in Europe and India, is knighted and elected to Parliament. In 1808 he begins a six year campaign to dislodge France from Portugal and Spain.

His efforts bear fruit on July 22, 1812 – two days before Napoleon begins his ill-fated march into Russia – when his 52,000 strong coalition army (Britain, Portugal, Spain) defeats the French at the ancient city of Salamanca, 120 miles west of Madrid. The victory makes Wellesley a national hero in Britain, and lays the groundwork for a final drive against the French in Spain.

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769-1852)

This culminates on June 21, 1813 at the Battle of Vitoria, in the northwest Basque region of the country.

While Napoleon has been plundering his army in Spain to support the invasion of Russia, General Wellesley has gathered and trained 110,000 troops (52,000 British, the rest from Portugal and Spain).

His attack at Vitoria overwhelms the much smaller French army (60,000 men) under Joseph Napoleon, and hurls them across the Pyrenees into southwestern France.

All hopes for a French resurgence in Spain disappear in October when Napoleon suffers another major setback in the east, at the Battle Of Leipzig.

After Joseph Napoleon hears of this loss, he officially abdicates the throne of Spain on December 11, 1813.

He will live on for another thirty years, first in America from 1817-32 (where he reportedly sells the crown jewels of Spain) and then back in Italy where he dies in 1868 and is buried in Les Invalides Paris, along with his younger brothers, Napoleon and Jerome.

Time: Spring 1813 – Spring 1814

The Sixth Coalition Occupies Paris

Napoleon’s 1812 defeat in Russia emboldens the conquered nations of Europe to once again seek their liberation from France.

Prussia makes the first move here, ending its alliance on December 30, 1812, then declaring war on March 16, 1813.

In response, Napoleon assembles a large invasion force and moves east, defeating a combined Prussian and Russian army under General Peter Wittgenstein, first at Lutzen on May 2 and then at Bautzen on May 20. Both sides lose roughly 40,000 in these battles.

With the momentum on his side, Napoleon inexplicably agrees to a truce (he calls it “the greatest mistake of my life’) which commences on June 4. This gives the allies a chance to regroup – and for Austria to join the coalition, tipping the manpower edge against France.

Despite this, Napoleon almost encircles the allied army under the Austrian, Karl Furst zu Schwarzenberg, just outside Dresden, on August 26-27. The allies lose almost 40,000 men here to only 10,000 for the French, and, were it not for Napoleon’s sudden illness, the rout could have been even more devastating.

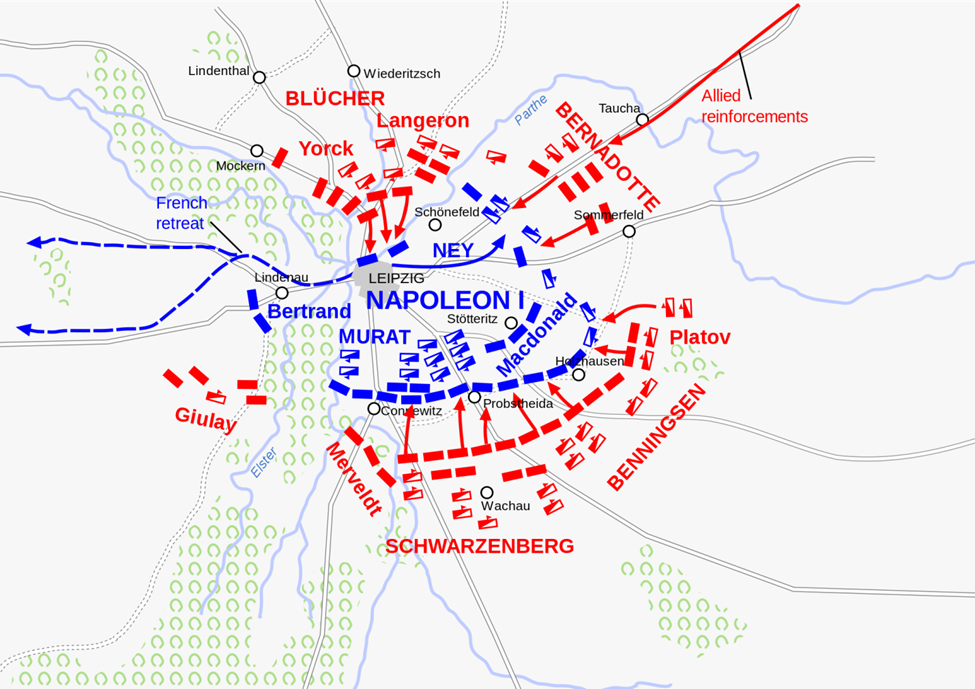

Six weeks now pass before the largest ground battle prior to World War I is fought over a four day span, October 16-19, 1813, at the Saxon town of Leipzig.

Napoleon Surrounded And Retreats At Leipzig

Napoleon fields 195,000 troops, Frenchmen and alliance forces from Italy, Poland and the German confederation. Together they are led by a host of famous field marshals – Michel Ney, Joachim Murat, Jacques MacDonald, Jozef Poniatowski.

But Napoleon is vastly outnumbered by the 365,000 man coalition army, comprising Russia, under Alexander I, the Austrians, commanded by Schwarzenberg, von Blucher’s Prussians, and the Swedes, under Crown Prince Charles John.

The Battle of Leipzig – also known as The Battle of Nations – seals Napoleon’s fate.

Over four days the two massive armies fight it out in towns north and south of the central French command in Leipzig. On the morning of October 18 the coalition launches a coordinated attack on all sides that endures for nine hours. By day’s end, Napoleon knows that the battle is lost, and he begins a successful retreat westward that continues into the 19th.

The French have suffered 38,000 killed or wounded and other 15,000 prisoners; coalition losses are put at 52,000.

Napoleon is now in headlong retreat, back across the Rhine toward Paris, with the vastly superior coalition army on his tail.

He has one last moment of brilliance left, in the Five Days campaign, from February 10-14, 1814.

The allies have three massive armies coming after him, which means that his only chance lies in beating them in detail. His first move, pitting his 30,000 men against von Blucher’s 110,000 some 50 miles northwest of Paris leads to four consecutive victories.

But the allied wave coming his way is now overwhelming.

The coalition, however, is not all together on the endgame it seeks.

Francis I of Austria and his foreign minister, Metternich, hope to conclude a treaty with Napoleon that would cost the French territorial gains, but leave the nation strong enough to avoid any chances of an English invasion of Europe.

But Alexander I of Russia in particular wants revenge, with Paris taken, Napoleon both deposed and humiliated, and the French army neutered. In the end, the coalition supports Alexander and marches on Paris. Their cause is helped by assurances to the war-weary population that the goal is to remove Napoleon, not harm the civilians.

After rear guard resistance is overcome, the allies occupy Paris on March 30, 1814 – the first time it has fallen in nearly 400 years.

Time: Spring 1814 – Spring 1815

Napoleon Is Banished To Alba But Returns For His Final Act

On April 14, 1814, the French minister, Talleyrand, suggests that Louis XVIII, a Bourbon, be chosen to replace Napoleon and to rule under a charter restoring pre-Revolutionary conditions. All sides agree on this option.

This leads to the Treaty of Paris, signed on May 30, 1814, restoring France’s 1792 borders and exiling Napoleon to the Isle of Alba, just off the southern coast of France, near Corsica, where he was born.

He spends 300 days on Alba before deciding to return to Paris, in response to rumors of popular uprisings against the monarchy, and fears that his country and army will be victimized by the Congress of Vienna dictates.

On March 1, 1815, he lands with 600 troops near the southern coastal town of Antibes and is back in Paris on March 19, with supporters flocking to his banner and with Louis XVIII in flight.

He quickly holds a plebiscite, showing the world that the French people back him.

His next step will be to restore France to its former preeminence in Europe.

The Napoleonic Empire: Key Events

| 1812 | 22 July French loss at Battle of Salamanca; Wellesley hero in Spain |

| 24 July Napoleon crosses into Russia | |

| 7 Sept Borodino | |

| 19 Oct Napoleon leaves Moscow and begins retreat | |

| 14 dec recrosses into France | |

| 30 dec – P withdraws from F alliance | |

| 1813 | Mar 16 P declares war on F |

| April 13 F initiates campaign April 13 F initiates campaign | |

| May 2 Lutzen 100 vs. 73; 20-18, F win | |

| May 20-21 Bautzen ; 96 vs 96, 20-20, F win | |

| June 4 Temporary armistice til Aug. 13 rebuild | |

| Austria joins coalition vs. N | |

| Aug 26-27 Dresden N 150,000/P 170,000; 10 vs 38, F wins | |

| June 21 Battle of Vittoria begins drive French out of Spain | |

| Oct 16-19 Leipzig N 195,000 P 365,000; loss 73,000; 54,000 – called battle of nations – allies win! Largest battle prior to WWI | |

| Dec 11 Joseph Bonaparte abdicate throne of Spain | |

| 1814 | Feb 10-14 Five Days Campaign west of Paris– brilliant Napoleon wins, but futile |

| March 30 Allies occupy Paris | |

| April 14 Louis XVIII placed on French throne | |

| May 30 Treaty of Paris ends war; Napoleon to Alba | |

| 1815 | Napoleon escapes Elba and returns to France |

| “Hundred Days” March 1-June 18, 1815. | |

| 7th Coalition vs. Britain and Prussia | |

| Waterloo |

Time: June 15, 1815

The French And Coalition Forces Arrive In Belgium

Despite Napoleon’s wishes, the Seventh Coalition countries – mainly Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia – will have none of this. They brands him an outlaw and reassemble a huge army to oust him.

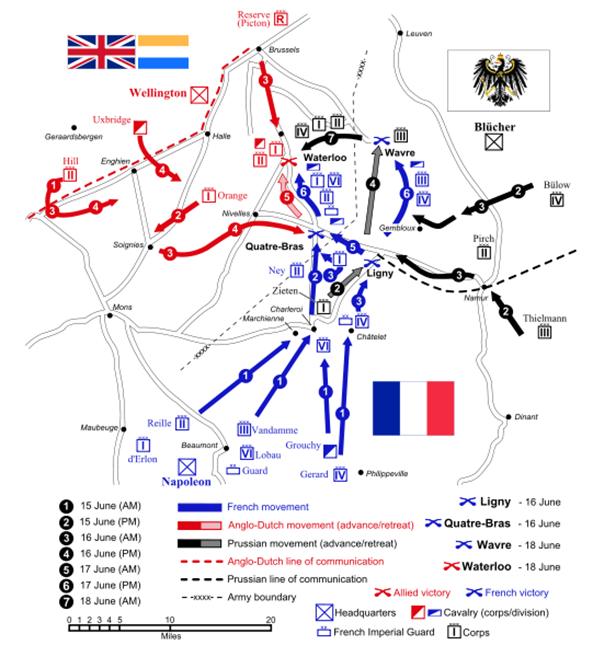

True to form when threatened, Napoleon goes on the offensive with his Armee du Nord, 130,000 strong and filled with veterans of his prior victories. He intends to take on the Coalition and attack it in detail, before it is able to concentrate the mass needed to overwhelm him.

He sets his sights on the heavily French oriented city of Brussels, 160 miles to the northeast of Paris, where he expects to encounter second tier British troops under Wellesley (soon to be Wellington) and worn out Prussians, under Blucher.

As Napoleon draws near, the allies anticipate that he will sweep north in an attempt at encirclement, but instead he dives straight between them – crossing the River Sambre on June 15 and dividing his force in two. At Quatre Bras, on his left, he places 70,000 troops under General Ney to block the English, while he moves to his right, eastward, with 60,000 me to attack Blucher’s force of 83.000 around the town of Ligny.

Ligny will be Napoleon’s final victory.

The Battle of Ligny opens at 2:30PM on June 16 and remains in the balance until Bonaparte sends in the Old Guard around 7:45 and drives the Prussians off the field to the west. During the fight, the 72 year old Blucher leads a charge, but is knocked unconscious when his horse is shot and falls on him.

But Napoleon knows that the Prussians have only been bruised at Ligny, not routed, and he worries that they will try to reunite with the British.

He needs to attack again before that can occur.

Time: June 18, 1815 — 2AM To 4:30PM

The Decisive Battle Of Waterloo Begins

Chateau Hougoumont Destroyed At The Battle of Waterloo

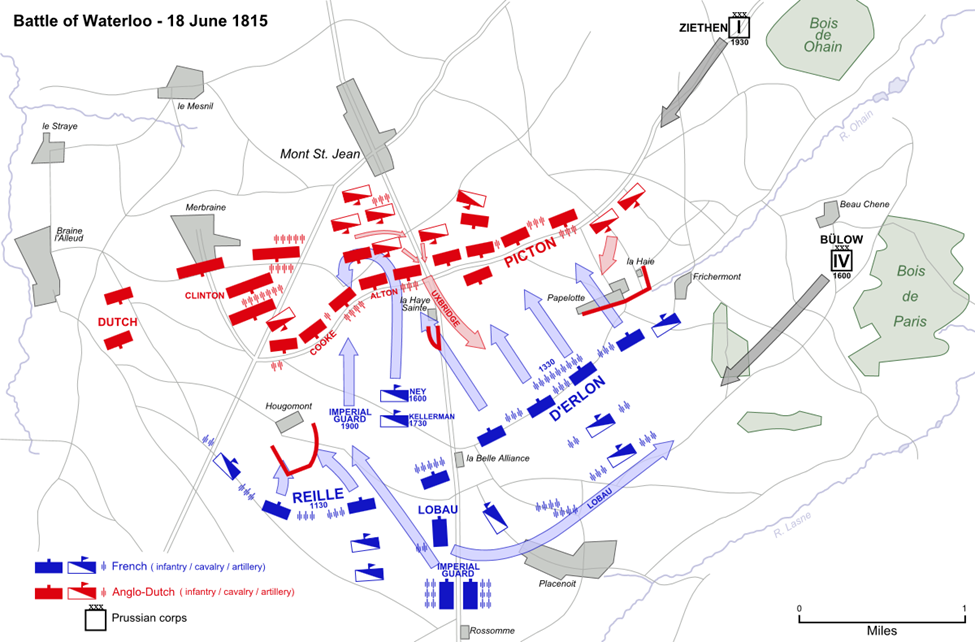

When Wellington hears the outcome at Ligny, he retreats from Quatre Bras, north to a high ground position he has staked out on a 2.5 mile ridge running east and west in front of the town of Mont St. Jean. A country road runs along the ridge, and intersects on the east with the main route toward Brussels, some 8 miles north.

The British General is a long-standing proponent of defensive warfare, and he deploys his forces in a way that will enable him to grind down any frontal assault on his center.

He does this by fortifying three sets of farmhouses and out-buildings., on his right flank, the Chateau Hougoumont, a half mile down from the ridge; on his near left La Haye Sainte, and on his far left Papelotte, along the road west toward the Prussians. Each site is manned and ready to send enfilading fire into all French troops trying to ascend the ridge.

Wellington has one other trick up his sleeve, and that is the ability to have his troops along the ridge lie down along the back slope while enemy artillery charges fly over their heads.

At 2AM on the morning of June 18, the Duke, headquartered further north in Waterloo, hears that Blucher will provide one Prussian corps to support him, if the battle occurs later in the day. This convinces him to make his stand on his current ground.

As the dawn arrives, the two sides each assemble roughly 70,000 men to do battle in a confined space of roughly 2.5 miles by 2.5 miles.

Napoleon rises at 8AM, takes breakfast, and rides north to review his troop alignments – his light infantry chasseurs in bright green, the light cavalry hussars, mounted cavalry dragoons and carabineers with long guns strapped to saddles, cuirassiers wearing metal breastplates, the towering grenadiers, chosen to lead assaults, in their blue and scarlet uniforms and bearskin headgear designed to add to their natural height, the cavalry lancers with their 10 foot wooden staffs tipped by a sharp steel blade, and the artillerymen, “his most beautiful daughters,” whose mastery and courage have won him many a victory.

The French Emperor is eager to conquer the British in his front and march into Brussels for his evening meal. While he has never met Wellington before, he remains typically confident. And his troops cheer and call out his name as he passes in front of them.

Meanwhile on the ridge, the Duke’s troops are lined up shoulder to shoulder according to the traditional 21 inch spacing proclaimed in the manuals. Nobody cheers his presence when he passes, because he has forbidden all such shows from within the ranks.

Napoleon is in no rush to attack. It has rained all night on the 17th, and the field of rye across which the French will make their assault is muddy and slippery. So he waits until 11:30AM, at which time he makes his first move of the day – against the crucial fortifications on his left at Hougoumont.

If Hougoumont falls, his canoners can ascend the ridge on the left, send enfilading fire down the entire British line, and claim a certain victory.

Artillery fire announces the French move, and it is quickly returned in kind: 4-12 pound solid iron balls bouncing along the ground and gouging body parts, sometimes 15-20 soldiers at a time, before being spent. Next comes the infantry, marching in order up the slope to the Chateau. The hand to hand fight there lasts for 90 minutes, the only action on the field.

When Hougoumont holds out, Napoleon next tries the British right, a heavy artillery barrage followed by massed infantry, 24 columns deep, coming up east of the Brussels road and past the fortified buildings of La Haye Sainte. Again the defenders drive the French back, led by a heroic cavalry charge behind Sir Thomas Picton, who is mortally wounded.

It is now 3PM and a pause leads many to think the battle is over. While the Duke is constantly visible along the ridge, Napoleon remains slouched in a field chair 1.5 miles back from the action, sending few orders and trusting Marshall Ney to manage the tactics. Amazingly the two do not meet face to face from 9AM until 7PM.

Around 4:00PM, Ney, evidently on his own, decides to test the British center. He does so in highly irregular fashion, using cavalry alone, unsupported by infantry.

Wellington responds by “forming squares,” the traditional defense against cavalry. The goal here is first to discourage the horses via planted pikes, and then to shoot them – leaving their armor clad riders stumbling on the field.

And this strategy succeeds. Some 12,000 French cavalrymen ascend the slope in magnificent order, only to be broken up into mingling clusters by the square’s concentrated firepower. By some estimates they re-form on twelve occasions to charge again and be rebuffed.

By 4:30PM Wellington, stationed openly in one of the squares, tells an aide. “the battle is mine, and if the Prussians arrive soon, there will be an end to the war.”

But when the French finally take La Haye Sainte, his confidence lessens – and the outcomes again hangs in the balance. Wellington has now shot his bolt, his troops are fought out, and his hope for survival rests on the appearance of Blucher’s Prussians to plug his gaps.

Time: June 18, 1815 – 7:00 To 9:30PM

Waterloo Is Lost And Napoleon Is Deposed For Good

This is Napoleon’s last best chance. He has held 14 regiments of his best troops, The Imperiale Garde, in reserve to the south. But when Ney requests them, Napoleon refuses to comply.

It is 7:00PM and the Emperor now knows that the Prussians, under Blucher and Bulow, are attacking his right flank, through Papelotte and, further south, at Plancenoit.

His options are running out. Does he use his reserves to hold off the Prussians or fling them up toward the British on the ridge? At 7:30PM he chooses the latter course.

He mounts his horse and leads five regiments of his Imperiale Garde north to the battle.

The Garde, the “Immortals,” famed for their courage – “the Garde dies, it does not retreat.”

Key Battle Sites on the Field at Waterloo

Many expect Napoleon himself to ride at the front of his troops, but he turns them over to Ney who has already had five horses shot from under him and is near exhaustion. Instead of taking the Brussels road up to the ridge, Ney veers left across the same ground as his prior cavalry charge. This adds 1,000 yards to the task, with the remains of the British artillery firing away.

As the Garde reaches the apparently accessible ridge, some 1,000 British infantrymen, the 1st Foot, under the command of Major General Peregrine Maitland, rise as if from nowhere, and shoot them down. And the Garde turns and flees back down the slope.

At this moment, the French have indeed lost the battle.

Wellington waves forward his troops, just as the Prussians break through from the east.

Napoleon rallies the remnants of the Imperiale Garde, south at La Belle Alliance along the Brussels road, and enables his troops to exit the field toward the south and west.

Around 9:30PM Wellington and Blucher meet up on the southern part of the field to seal their victory. The Duke has lost 15,000 killed and wounded; Blucher another 7,000.

Napoleon has lost 15,000 men – and his empire.

As the Coalition army closes again on Paris on June 24, Napoleon abdicates. He surrenders personally on July 22 to the British, seeking “hospitality and the full protection of their laws.”

According to the traditions of the age, Napoleon again suffers banishment not execution, this time to the Island of St. Helena, one of the most isolated in the world, off southwestern Africa. He lives there until his death in 1821, presumably of stomach cancer. In 1840 his remains were shipped back to Paris, where he lies in Les Invalides.

Le jour de gloire has come and gone – for Napoleon and for revolutionary France.

le jour de gloire s’en est allé” — the day of glory has vanished

Time: 1814-1914

The World Reshaped After Waterloo

After the turmoil of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the monarchs of Europe are eager to restore their authority and permanence by creating a stable balance of power between their nations.

They use the 1814 Congress of Vienna and the 1815 Paris Peace Conference to attempt to achieve these ends.

At the center of the diplomacy lies ongoing fear of France and a wish to contain any further thoughts of expansion on her part.

Within France itself, a “constitutional monarchy” is created under the Bourbon King Louis XVIII, Napoleon and his heirs are banned for life, reparations of 700 million francs are demanded and foreign troops remain on French soil until 1818.

In addition, steps are taken to surround her with more formidable border states:

Napoleon’s Tomb at Les Invalide Paris

- To her southwest, along the Pyrenees, the Bourbon King Ferdinand VII is returned to the throne of Spain.

- Her southeastern border with Italy is controlled by the Kingdom of Sardinia/Piedmont backed by Austria which gains control of Milan and Tuscany.

- Directly east of central France lie a jumble of states sharing both French and German roots, including what will become Switzerland, Alsace-Lorraine and Luxemburg.

- But to her northeast lie two sizable forces – the first being the new United Netherlands, with its seven provinces, including the two Hollands, under King William I of Orange.

- And then Prussia, which has traded off some of its claims to Poland to acquire a toehold along both banks of the Rhine River, in the incredibly resource rich Ruhr Valley.

When the Prussian minister Bismarck finally patches together a united Germany in 1867, France will have found a powerful foe all along its eastern border.

What of Britain, Napoleon’s original nemesis from the time he came to power?

Their prize is absolute control of the seas with the Royal Navy and of their colonial empire stretching around the globe.

In the end, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars have shaken the monarchical pillars of Europe from Lisbon to Moscow. But, by in large, the work done in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna and The Treaty of Paris restore their crowns and deliver relative stability over the next one hundred years.