The Ostend Manifesto Embarrasses President Pierce

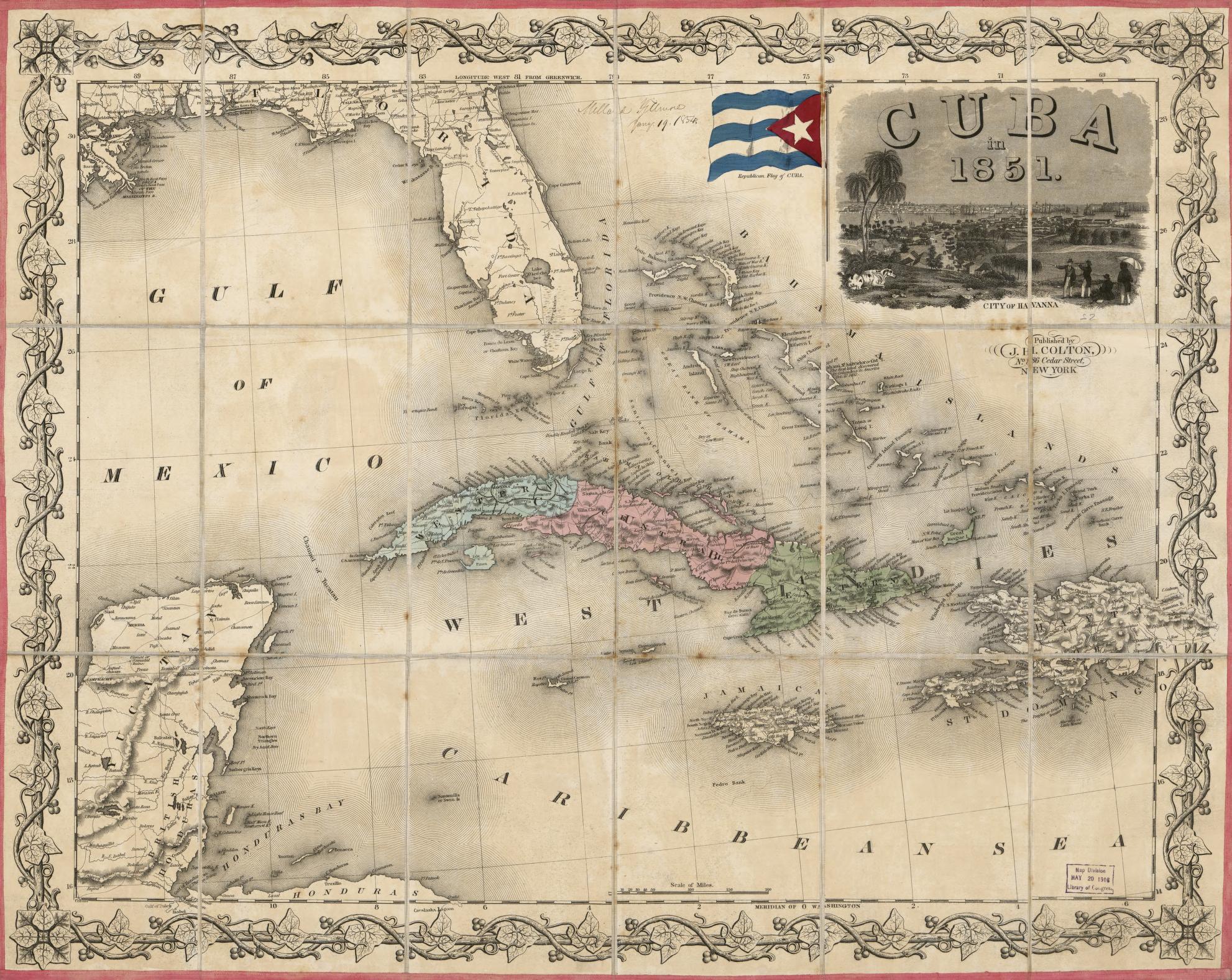

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, origins go back to 1853 when President Pierce begins his term. By that time Northern resistance to expanding slavery into the west is on the rise. This leads Southerners to explore options outside of the U.S., with Cuba as a prime candidate.

Interest in acquiring Cuba traces all the way back to Jefferson in 1803 who declares it “the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States.” After the island nation becomes the world’s leading producer of sugar, supplying some 30% of total global demand, Polk’s offers $100 million to buy it in 1848, but Spain refuses to sell.

From there, seizure by force comes into play with the filibusterer Narciso Lopez making the first move. He is backed by Mississippi Governor, John Quitman, and lands on Cuban soil with 600 men in May 1850. He seizes the town of Cardenas, but a lack of local support for overthrowing the Spanish government causes him to retreat to New Orleans. He tries again in August before being captured and executed in Havana. In turn Quitman is indicted and forced to resign.

Pierce owes his presidency to Southern support and, feeling the political pressure, he calls upon three diplomats – Pierre Soule (Spain), James Buchanan (UK) and James Mason (France) – to make a joint action proposal. They meet in Ostend, Belgium, and send their recommendation to Pierce in October, 1850. It begins by arguing that “Cuba belongs naturally to that great family of states of which the Union is the providential nursery.”

The Ostend Manifesto recommends that America try once again to purchase Cuba

The outspoken successionist Mason then conjures up the preposterous notion that Cuba is “exceedingly dangerous” to the U.S. since a Haiti-like insurrection there among its Blacks might trigger slave uprisings across the South.

The Ostend Manifesto recommends that America try once again to purchase Cuba. But, if that fails, it contends “we shall be justified in wrestling it from Spain.”

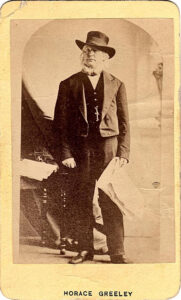

Pierce is distressed by a document supporting a war with Spain and tries hard to keep it under wraps. But the New York Herald makes the contents public and New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley calls the plan a Southern attempt to steal more land for slavery.

The criticism plays out from there. Foreign ministers in Madrid, Paris, and London denounce the threat of force, and an embarrassed Pierce instructs Soule to end his negotiations, which leads to his immediate resignation.

The Ostend Manifesto will prove to be no more than a historical footnote, but at the time it amplifies the rift between the South and the North, including within the Democratic Party, and further erodes any possibility of a second term for Franklin Pierce.

Learn the full text of Ostend Manifesto.